The Effect of General Anesthesia on the Hemodynamic Assessment of Aortic Stenosis in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2025. doi:10.25270/jic/25.00247. Epub December 23, 2025.

Abstract

Objectives. Anesthetic agents (general anesthesia [GA]) used during transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) have been observed to affect intracardiac pressures when measured by catheter and echocardiography. The authors hypothesized that, during GA-employed TAVR, there is significant reduction in the invasively measured aortic valve gradients (AVG) as a result of the GA.

Methods. The authors performed a retrospective analysis of 298 patients undergoing TAVR. All patients had preoperative TTE and procedural AVG. Preprocedural AVG measured by TTE were compared to the AVG measured invasively after GA induction. The authors investigated the relationship between AVG discrepancy and the types of GA agents used and compared various hemodynamic parameters before and after GA induction.

Results. There were statistically significant reductions in both the maximum (mean reduction: 16.99 mm Hg; P<.001; 95% CI, 14.70-19.27 mm Hg) and mean AVG (mean reduction: 7.084 mm Hg; P <.001; 95% CI, 5.672-8.496 mm Hg) when measured invasively under anesthesia compared with awake pre-anesthesia AVG by TTE. There were statistically significant reductions in blood pressure (mean reduction: 16.41 mm Hg; P <.001; 95% CI, 12.26-20.56 mm Hg) and heart rate (mean reduction: 6.299 bpm; P < .001; 95% CI, 3.735-8.863 bpm), and a statistically significant increase in stroke volume (mean increase: 8.212 mL; P < .001; 95% CI, 3.559-12.86 mL). Further linear regression analysis proved that the aforementioned AVG discrepancy is directly related to AS severity.

Conclusions. In patients undergoing TAVR with GA, there is a significant reduction in AVG when compared with the preprocedural TTE measurements. This phenomenon is directly related to AS severity.

Introduction

Nonrheumatic aortic stenosis (AS) in patients older than 65 years leads to significant morbidity and mortality.1 Valve intervention in patients with symptomatic severe AS leads to a significant reduction in mortality and enhances quality of life.1 The treatment of AS in patients older than 65 years has changed over the last 10 years to include both surgical valve replacement (SAVR) and transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). Multiple randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that TAVR is as effective as SAVR in the treatment of AS with a significant reduction in post-procedural complications in all surgical risk cohorts.2 This has led to a significant increase in TAVR procedures.3

The assessment of AS is routinely done with transthoracic echocardiography (TTE).4 The estimation of AS severity and the subsequent selection of patients who are candidates for TAVR is routinely done by TTE, which allows for real-time high-resolution imaging of the valve and leaflet mobility. Doppler echocardiography allows for estimation of pressure gradients across the stenotic valve.4 Hemodynamic measurements together with anatomic measurements of the left ventricle obtained from 2-dimensional imaging provides anatomic dimensions of the aortic valve area (AVA) that are comparable to cardiac catheterization-based measurements of the aortic valve orifice.5 Anatomic and hemodynamic data obtained from the TTE are now considered to provide guidance in decision making about the need for valve intervention in most patients.6

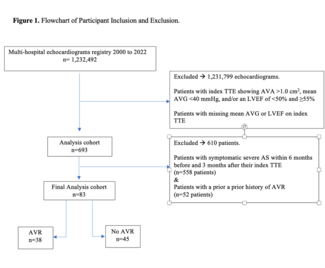

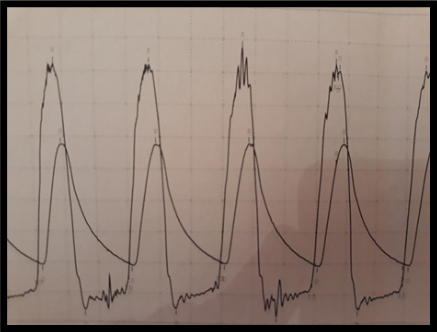

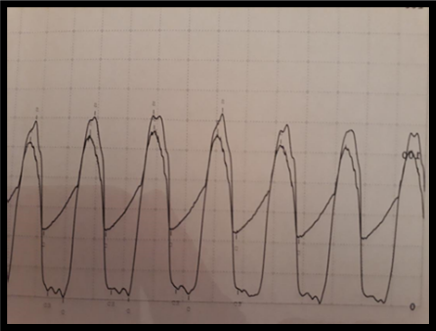

TTE has been shown to correlate with hemodynamics obtained during invasive cardiac catheterization procedures. While performing TAVR, it was noted that the invasive assessment of transvalvular gradients at the time of the intervention was significantly reduced when compared with the valve hemodynamics from awake TTE (Figure 1). This difference was especially notable when patients were intubated and sedated; some interventions were abandoned in fear the AS was not of a severity that required intervention. This hemodynamic effect was most notable when general anesthesia was used during the TAVR procedure.

The effect of loading conditions in the left ventricle is now recognized to affect the transvalvular hemodynamics in AS.1 Through this study, we sought to describe the effect of general anesthetic agents on the invasive measurements of AS in patients with severe AS undergoing TAVR in the setting of general anesthesia (GA).

Methods

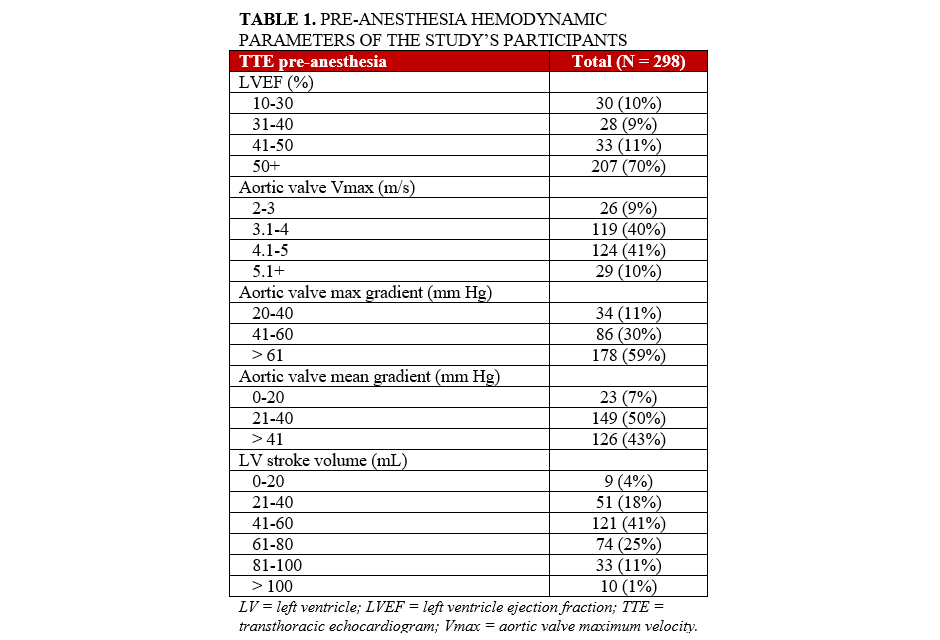

This study was an investigator-initiated, single-center, retrospective review of patients undergoing transfemoral TAVR over a period of 4 years. The Human Investigation Review Board at Tufts Medical Center granted consent to perform this retrospective database study for information regarding all patients who underwent TAVR at Tufts Medical Center from 2014 to 2018. All patients had complete preoperative TTE, post-anesthesia preoperative transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), and procedural invasive aortic valve gradients (AVG). We included only patients who had general anesthesia administered and for whom both preoperative echocardiographic and intraoperative hemodynamic parameters were recorded. Pre-procedural echocardiographic data was available for all the patients during the time period, as was invasive hemodynamic data at the time of TAVR prior to valve deployment, including aortic and intraventricular pressure waveforms. Intraoperative echocardiographic data (such as LVEF and stroke volume [SV]) was derived from the post-anesthesia preoperative TEE electronic record, signed either by an anesthesiology or a cardiology attending (Table 1). Information regarding administration of intravenous vasoactive agents, anesthetic agents, opioids, and sedatives was extracted from the anesthesia record for all of our patients. Procedural parameters collected for analysis included the following: (1) blood pressure, (2) heart rate, and (3) TEE-derived left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and SV.

Statistical analysis

Our statistical analysis was based on simple t-testing of various TAVR hemodynamic parameters, comparing pre-TAVR findings with those under GA. Moreover, in order to further investigate for a possible relationship between gradient discrepancy and various demographics and hemodynamic and operational parameters, we performed a linear regression analysis (both univariate and multivariate) of 27 such parameters in total. For our statistical analysis, SPSS (IBM) as well as RStudio statistical packages (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) were used.

Results

Patient characteristics

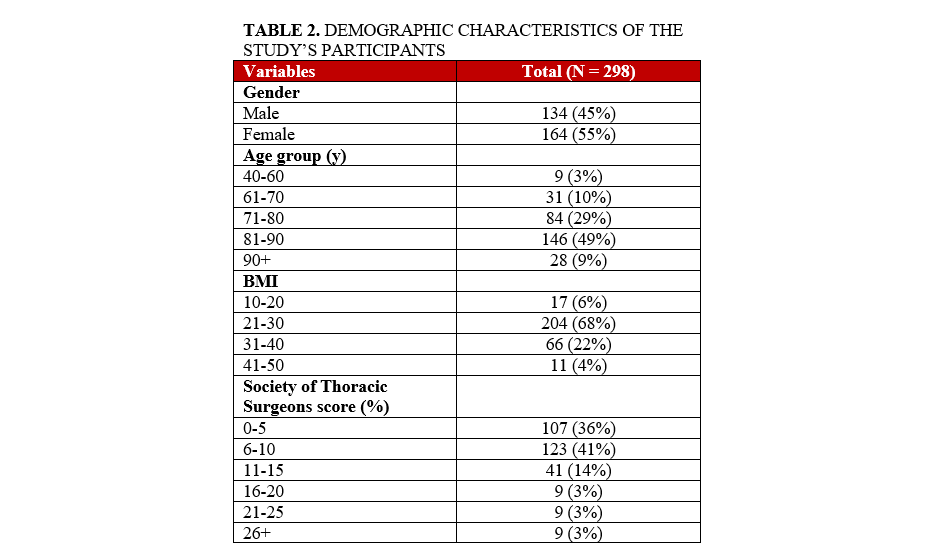

We performed a retrospective analysis of 298 patients who underwent successful TAVR at a single center (Tufts Medical Center) using a single commercially available TAVR valve (Edwards LifeSciences). Both sexes were similarly represented (134 [45%] male vs 164 [55%] female patients). Forty-nine percent of the patients studied were between 80 and 90 years old, and 67% of the patients had a body mass index between 21 and 30. The majority (64%) of the patients studied were considered high or exceptional risk for surgical aortic valve replacement (Table 2).

Comparison of pre- and intra-procedure aortic valve gradients

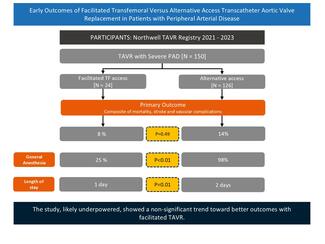

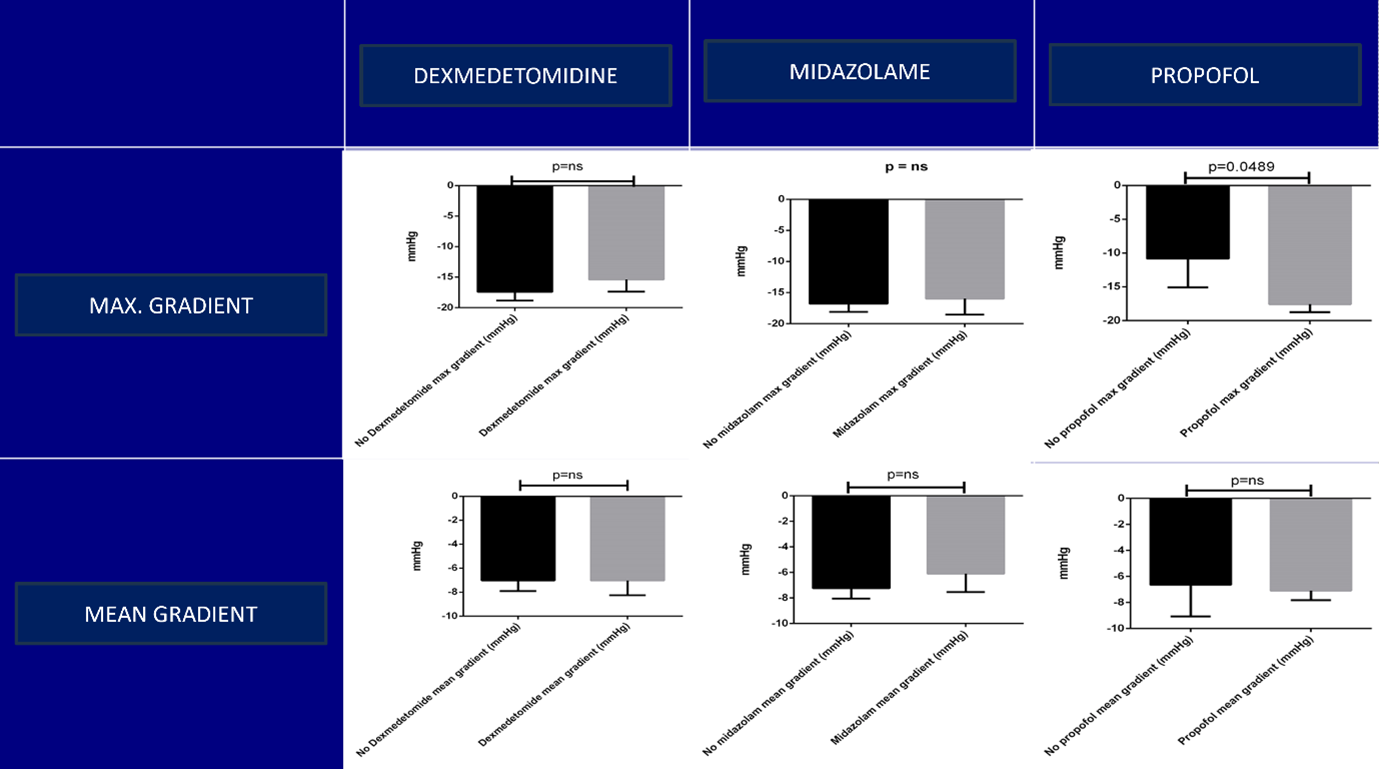

There were statistically significant reductions in both the maximum AVG (mean reduction: 16.99 mm Hg; P < .001; 95% CI, 14.70-19.27 mm Hg) and mean AVG (mean reduction: 7.08 mm Hg; P < 0.001; 95% CI, 5.67-8.5 mm Hg) when measured invasively under anesthesia compared with awake pre-anesthesia maximum and mean AVG measured by TTE. There were statistically significant reductions in blood pressure (mean reduction: 16.41 mm Hg; P < .001; 95% CI, 12.26-20.56 mm Hg) and heart rate (mean reduction: 6.299 bpm; P < .001; 95% CI, 3.74-8.86 bpm), and a statistically significant increase in SV (mean increase: 8.212 mL; P < .001; 95% CI, 3.559-12.86 mL) after induction with general anesthetic agents (GAA). There was no change in LVEF after induction with GAA. Of the GAA used, only propofol was found to have a significant effect on the AVG reduction (mean reduction: 6.743 mm Hg; P = .0489; 95% CI, 0.03-13.45 mm Hg) (Figure 2).

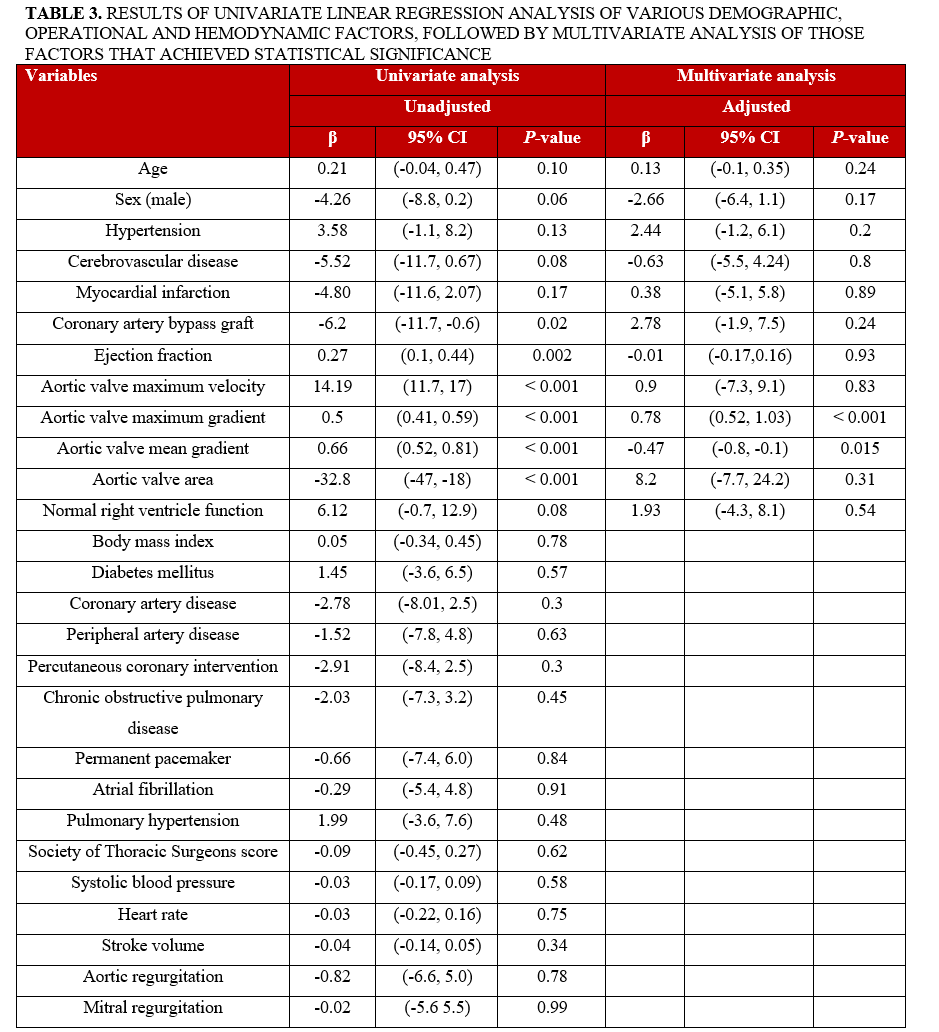

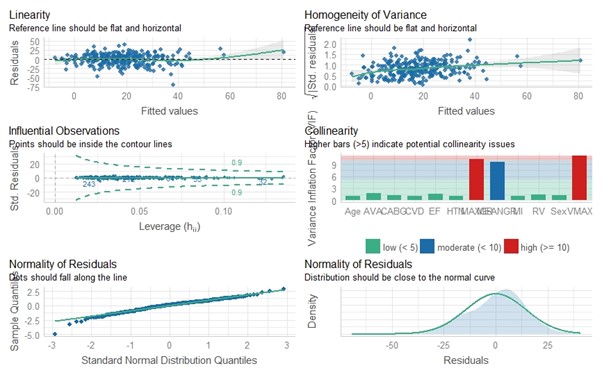

We then proceeded to investigate which patient characteristics and comorbidities as well as hemodynamic parameters might affect the aortic valve maximum gradient (MaxGr) variation between pre- and post-anesthesia induction (we chose this AS metric because it was the one most prominently affected by anesthesia induction in our study). Of the 27 independent variables studied, 6 (previous coronary artery bypass graft, ejection fraction [EF], aortic valve maximum velocity [Vmax], MaxGr, aortic valve mean gradient [MeanGr], and AVA) proved to be statistically significant in the univariate analysis. In performance of a multivariate analysis, only 2 variables maintained their statistical significance (MaxGr [P < .001] and MeanGr [P < .015]) (Table 3). Furthermore, when tested for collinearity, they both presented an elevated variance inflation factor (VIF) (10.241 and 9.621, respectively); this was expected, as both variables are derived using the same method of Doppler waveform measurement. Vmax was also extracted from the aforementioned measurement, so it was not surprising that its VIF was elevated as well (11.228) (Figure 3). The above findings clearly show that the AVG measurement discrepancy phenomenon we describe is directly proportional to the AS severity: the more severe the AS (and therefore the higher its gradients are measured), the more pronounced the discrepancy of AVG measurements is poised to be before and after GA induction.

Discussion

At first glance, our study’s findings seem a pathophysiologic paradox, since an investigator would anticipate the exact opposite results: as aortic pressure normalizes and, at the same time, LV pressure remains at the same height, an increase of the AVG would be normally expected. Furthermore, this paradoxical phenomenon seems to have a negative correlation with the aortic valve size: the smaller the AVA, the more probable (and/or pronounced) the drop at the aortic valve gradient is when the patient is under GA. Our team has developed a theory that may serve as a possible explanation of our study’s findings.

The pendulum theory

According to the 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease,7 AS is classified into the following categories:

- High-gradient AS (valve area < 1 cm2, mean gradient > 40 mm Hg). Severe AS can be assumed irrespective of whether LVEF and flow are normal or reduced.

- Low-flow, low-gradient AS with reduced EF (valve area < 1 cm2, mean gradient < 40 mm Hg, EF < 50%, SV index [Svi] < 35 mL/m2). Low-dose dobutamine echocardiography is recommended in this setting to distinguish truly severe AS from pseudosevere AS, which is defined by an increase to an AVA of greater than 1 cm2 with flow normalization. In addition, the presence of flow reserve (also termed contractile reserve; increase of SV > 20%) has prognostic implications because it is associated with better outcome.

- Low-flow, low-gradient AS with preserved EF (AVA < 1 cm2, mean gradient < 40 mm Hg, EF > 50%, Svi < 35 mL/m2). This is typically encountered in older adults and is associated with small ventricular size, marked LV hypertrophy, and often a history of hypertension. The diagnosis of severe AS in this setting remains challenging and requires careful exclusion of measurement errors and other reasons for such echocardiography findings. The degree of valve calcification by multispiral computer tomography is related to AS severity and outcome. Its assessment has therefore gained increasing importance in this setting.

- Normal-flow, low-gradient AS with preserved EF (AVA <1 cm2, mean gradient < 40 mm Hg, EF > 50%, SVi > 35 mm Hg). These patients will in general have only moderate AS.

In our study we have shown that, under GA, SV increases along with AVG reduction. The exact same hemodynamic alterations are observed in patients who undergo dobutamine echocardiography, which, in cases of pseudosevere AS, results in AVG reduction as well as SV increase to achieve flow normalization. We could therefore argue that quite the same hemodynamic phenomenon of flow normalization across the aortic valve occurs when the human heart is under GA and dobutamine stress effect. The aortic valve hemodynamics seem to follow a pendulum pattern, the extremes of which (GA sedation on one side and stress exercise on the other) result in general cardiac performance augmentation and transvalvular flow optimization. The difference between these 2 pendulum extremes is that, while in the case of stress echocardiography contractile reserve activation is established as the responsible mechanism, our study’s side of the pendulum pathophysiological mechanism remains quite unclear.

During TAVR, the patient’s general condition parameters (supine position, intubated under GA with full aerometric, as well as hemodynamic control) is referred to as “loading conditions.” If our theory is true, it seems that loading conditions in general provide a hemodynamic environment that is next to ideal for aortic transvalvular flow. Our study did not analyze each parameter of the loading conditions separately and, therefore, cannot determine each parameter’s individual role in AVG reduction. Separate analysis of the effect of each of the main GAAs that were administered during TAVR showed that only propofol has a role in MaxGr reduction; at the same time, the reduction on mean gradient was statistically insignificant. Further verification of this theory could be facilitated by performing stress echocardiography on the patients who exhibit extreme AVG reduction under GA and observing whether they actually belong to the low-flow group of actual pseudosevere AS, in addition to whether contractile reserve is also present in these patients.

Limitations

Our study was a retrospective review and is thus subject to the limitations related to such studies. As there was not consistent right heart catheterization at the time of the TAVR procedure, our data about SV alterations were extracted by (indirect) TEE measurements, which present pitfalls because of the location of the imaging probe and the limited ability to align the Doppler beam parallel to the left ventricular outflow. Moreover, none of the loading conditions could be individually studied retrospectively (apart from the anesthetic pharmacological agents). As a result, our understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanism of the phenomenon we describe remains unclear.

Conclusions

In patients undergoing TAVR under GA, there is a consistent and significant reduction in AVG attributed to the effect of the GAAs used during induction when compared with the pre-procedural measurements with TTE. Interpretation of the periprocedural hemodynamics should take into consideration this effect when compared with awake, noninvasive AVG measured with TTE. This reduction in AVG correlates inversely with AVA and can possibly be (at least qualitatively) predicted by aortic valve hemodynamics. Although the pendulum theory seems to explain our findings to a degree, further investigation with prospective studies is needed to establish the exact pathophysiological mechanism of this phenomenon.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Stefanos Votsis, MD, MSc1,2; Hassan Rastegar, MD3; Andrew Weintraub, MD, FACC4

From the 1Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, Augusta, Georgia; 2Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece; 3Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts; 4Signature Healthcare-Brockton Hospital, Brockton, Massachusetts.

Disclosures: The authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Address for correspondence: Stefanos Votsis, MD, MSc, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, 1120 15th St, Augusta, GA 30912, USA. Email: stefanosvotsis@yahoo.com

References

1. Whitener G, McKenzie J, Akushevich I, et al. Discordance in grading methods of aortic stenosis by pre-cardiopulmonary bypass transesophageal echocardiography. Anesth Analg. 2016;122(4):953-958. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001099

2. Mo Monin JL, Quéré JP, Monchi M, et al. Low-gradient aortic stenosis: operative risk stratification and predictors for long-term outcome: a multicenter study using dobutamine stress hemodynamics. Circulation. 2003;108(3):319-324. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000079171.43055.46

3. Levy F, Laurent M, Monin JL, et al. Aortic valve replacement for low-flow/low-gradient aortic stenosis operative risk stratification and long-term outcome: a European multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(15):1466-1472. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.067

4. Hachicha Z, Dumesnil JG, Bogaty P, Pibarot P. Paradoxical low-flow, low-gradient severe aortic stenosis despite preserved ejection fraction is associated with higher afterload and reduced survival. Circulation. 2007;115(22):2856-2864. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.668681

5. Clavel MA, Dumesnil JG, Capoulade R, Mathieu P, Sénéchal M, Pibarot P. Outcome of patients with aortic stenosis, small valve area, and low-flow, low-gradient despite preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(14):1259-1267. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.054

6. Mehrotra P, Jansen K, Flynn AW, et al. Differential left ventricular remodelling and longitudinal function distinguishes low flow from normal-flow preserved ejection fraction low-gradient severe aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(25):1906-1914. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eht094

7. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al; ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(7):561-632. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395