Survival With Aortic Valve Replacement in Asymptomatic Individuals With Severe Aortic Stenosis and a Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction of 50% to 54%

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2026. doi:10.25270/jic/25.00332. Epub January 15, 2026.

Abstract

Objectives. Severe aortic stenosis (AS) with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 50% to 54% is associated with worse outcomes than an LVEF greater than or equal to 55%. European guidelines consider aortic valve replacement (AVR) a Class IIa indication for asymptomatic patients with an LVEF of less than 55%, whereas American guidelines recommend AVR when the LVEF is less than 50%. The authors assessed outcomes of AVR vs conservative management in this range where guidelines differ.

Methods. A registry was created for individuals with severe high-gradient AS (AVA ≤ 1 cm²), an LVEF of 50% to 54%, and a mean gradient greater than or equal to 40 mm Hg from 2000 to 2022 using queries of transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) reports. Only asymptomatic cases were included; time-zero was defined as the time of the index TTE, and both AVR (considered as a time-dependent covariate) and mortality could occur at any point after. Proportional hazard modeling assessed the AVR-mortality association, with subset analyses for individuals with AVAs of less than 0.9 cm² and less than or equal to 0.75 cm².

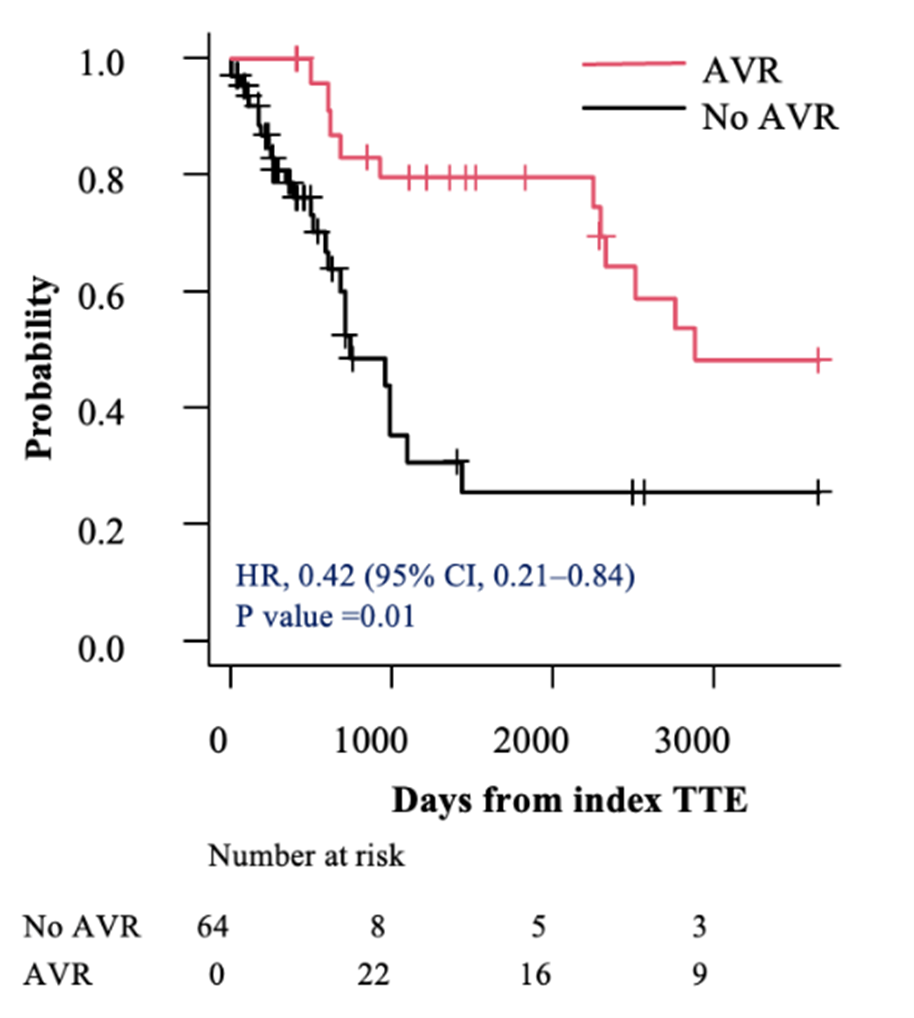

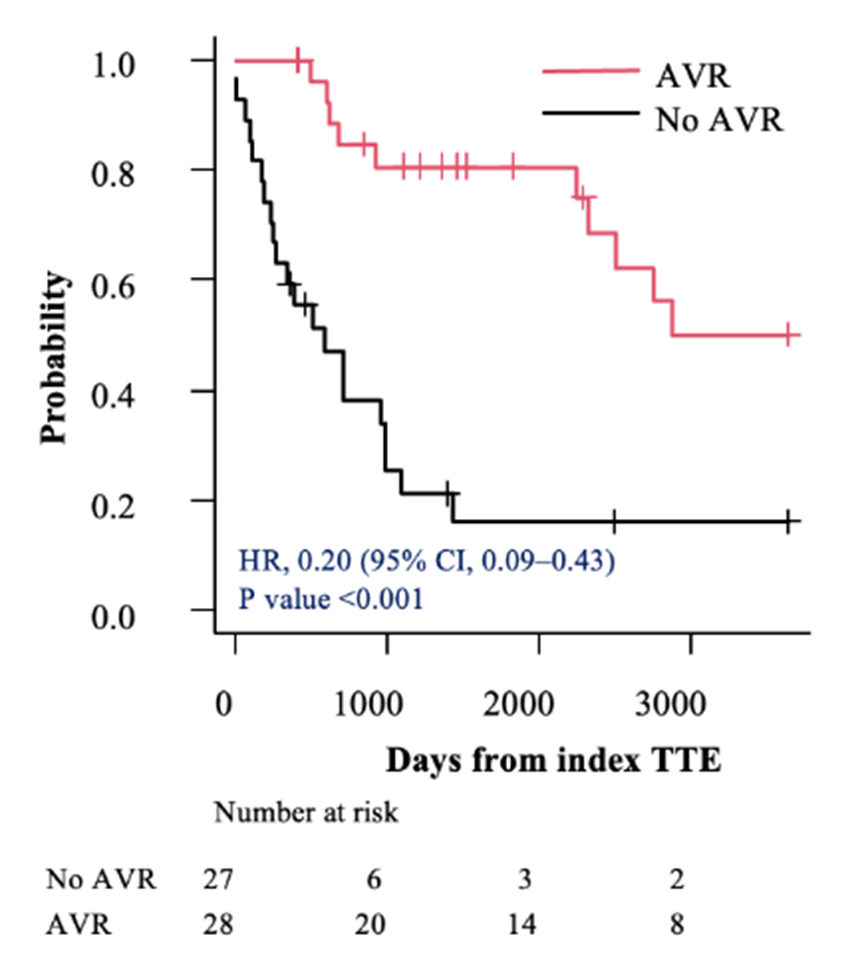

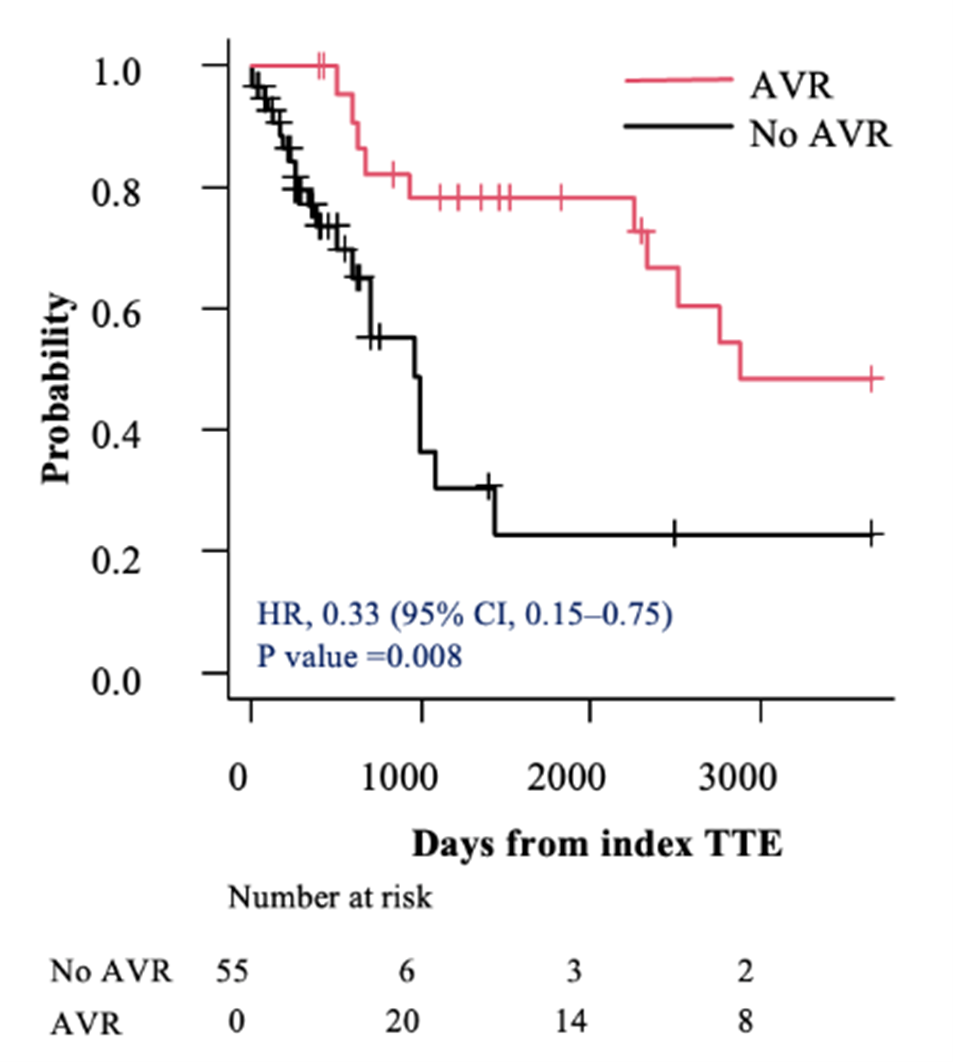

Results. Among 693 included individuals, 83 were asymptomatic at their index TTE. Of these, 38 (45.8%) underwent AVR within 2 years. After adjusting for immortal time, individuals with AVR had a trend toward decreased mortality (HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.31-1.01; P = .054). Among individuals with AVAs of less than 0.9 cm² and less than or equal to 0.75 cm², AVR was associated with improved survival (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.21-0.84; P < .01 and HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.15-0.75; P < .008, respectively).

Conclusions. AVR within 2 years was associated with improved survival among asymptomatic individuals with high-grade severe AS and an LVEF of 50% to 54%.

Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is one of the most common valvular heart diseases, predominantly impacting older adults.1,2 When severe AS becomes symptomatic and is left untreated, there is a substantial risk of mortality, exceeding 50% within 1 year.3,4 Both the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) and European Society of Cardiology/European Association for CardioThoracic Surgery (ESC/EACTS) guidelines recommend intervention when symptoms are present.5-7

On the other hand, the optimal timing for intervention in asymptomatic severe AS is still a subject of debate.8 In the recent updates to valvular heart disease management guidelines by the ACC/AHA and ESC/EACTS, notable differences emerge in the approach to managing asymptomatic individuals with severe AS.5-7 Both guidelines recommend aortic valve replacement (AVR) for asymptomatic severe AS with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of less than 50%. However, they have important differences in recommendations when there is potentially subclinical ventricular dysfunction with an LVEF of 50% to 59%. One of those differences pertains to the lower end of this range, from 50% to 54%. Unlike the American guidelines, the ESC/EACTS guidelines suggest a Class IIa indication for AVR when the LVEF is less than 55%, without any requirement for decreasing LVEF.5-7 Accordingly, there is no clear consensus regarding the management of individuals with a low-normal LVEF (eg, LVEF 50%-54%) with severe asymptomatic AS. Regardless of initial management strategy, individuals with severe AS and an LVEF of 50% to 54% have poorer long-term outcomes compared with those with an LVEF greater than or equal to 55%.9 Although recent clinical trials have suggested that early intervention improves outcomes in individuals with severe asymptomatic AS and preserved LVEF (LVEF ≥ 50%), these trials did not specifically focus on severe asymptomatic individuals with an LVEF in the lowest portion of that range (50%-54%).10-12

Given the narrow LVEF window and differences between American and European guidelines, trials specific to this group are unlikely to be performed. As such, resolving this discrepancy requires careful analyses of real-world clinical data, with large, linked observational datasets being essential to provide more statistical power than trials. One of the difficult aspects of assessing comparative effectiveness with observational data, however, is immortal time bias. Unlike in a prospective “intention to treat” randomized trial, looking backward with observational data tends to falsely exaggerate the benefits of interventions because those who die early count as “medical management” even if they would have received interventions later. We have previously shown that time-dependent covariates that count individuals as “medical management” or intervention at different times can correct this important source of bias in observational data.13,14

In that context, we used open-source natural language processing (NLP) tools to construct a retrospective observational registry and account for both case selection differences and immortal time. Specifically, we sought to compare the outcomes of asymptomatic individuals with severe high gradient AS and an LVEF of 50% to 54% who received AVR with those who did not receive AVR. We hypothesized that individuals with severe high gradient AS who were asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis (index transthoracic echocardiogram [TTE]) would have lower mortality if they received AVR within 2 years compared with conservative management.

Methods

Patient selection

A retrospective study was conducted using a multihospital echocardiography registry, which included 1 232 492 echocardiograms performed between January 1, 2000, and November 22, 2022. Utilizing NLP, we first extracted echocardiographic data from electronic medical records sourced from 7 hospitals within the Mass General Brigham (MGB) network.15 These algorithms are available for public use and free of charge on the open-source Canary NLP web site, subject to compliance with the terms, including appropriate citation.16-18 The efficacy of NLP in extracting and categorizing data from echocardiography reports has been previously established.19,20 To ensure data accuracy, manual checks of written information from TTE reports were conducted (no direct image adjudication).

Our analytic goal was to use this very large database to detect a very specific population of asymptomatic individuals within a small LVEF range. Therefore, our inclusion criteria consisted of individuals with severe AS, defined as an aortic valve area (AVA) of less than or equal to 1.0 cm2 (calculated by the continuity equation), a high gradient characterized by a mean pressure gradient across the aortic valve (AVG) of greater than or equal to 40 mm Hg, and an LVEF greater than or equal to 50% and less than 55%. We defined time zero as the date of index TTE. For those with multiple TTEs meeting these criteria, the initial one was designated as the index TTE. The selected EF and mean AVG range adhered to the 2021 ESC/EACTS guidelines for managing severe asymptomatic AS. The query concluded on November 22, 2022, ensuring a minimum of 1 year of follow-up data.

Analysis cohort

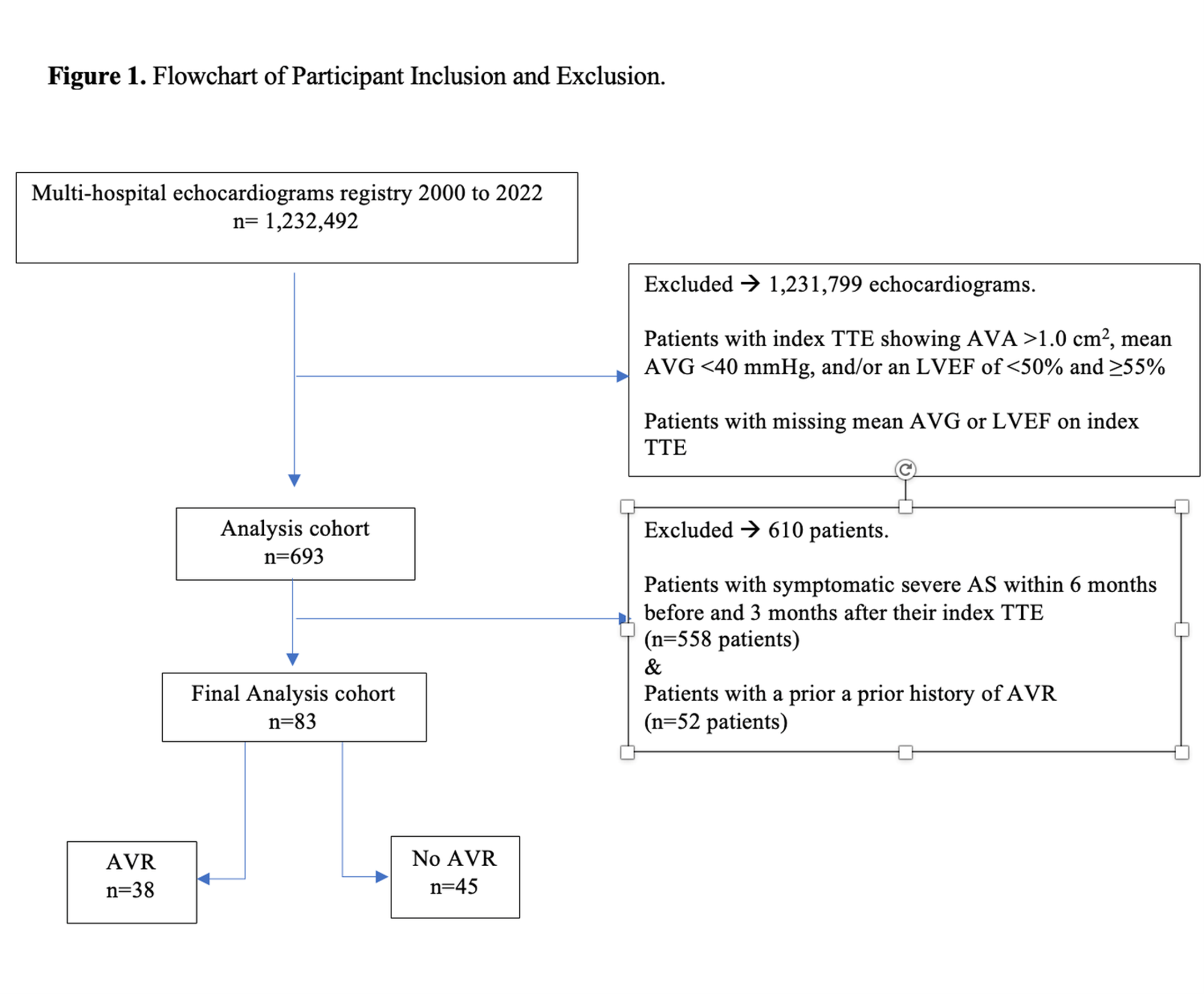

Among the 1 232 492 echocardiograms in the database, 693 individuals initially met the criteria for severe, high-gradient AS with an LVEF of 50% to 54%. Exclusion criteria included individuals whose TTE reports lacked AVA, mean AVG, or LVEF. Individuals with a history of prior AVR were also omitted from the study (Figure 1). Additionally, individuals reporting any symptoms (heart failure, angina, presyncope, or syncope) detected on chart review within 6 months prior to and 3 months following their index TTE were excluded. This time window was chosen to mirror the clinical decision to choose AVR or not as an initial strategy in asymptomatic patients. Mindful that these individuals may eventually develop symptoms, individuals who had AVR were then re-reviewed with physician chart review to determine the proportion who developed symptoms eventually prior to AVR. The assessment of symptom status was adjudicated with direct physician chart review (M.E.). Chart reviews were conducted between June and September 2024.

The utilization of AVR was examined up to 2 years following the index TTE, categorizing individuals into distinct groups: those undergoing AVR within 2 years and those not undergoing AVR within 2 years. Clinical data were systematically gathered from chart review, encompassing factors such as age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), medical history (hypertension [HTN], diabetes mellitus [DM], coronary artery disease [CAD], peripheral artery disease, chronic kidney disease, valvular heart disease, atrial fibrillation or flutter), procedural history (coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG] or percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]), lifestyle factors (smoking status), and comorbidities (dementia, cerebrovascular accident [CVA] or transient ischemic attacks [TIA], liver disease, connective tissue disorder, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], and cancer). Additionally, we included basic laboratory values (hematocrit, platelet count, and creatinine), severe AS etiology, and echocardiogram data (AVA, mean AVG, LVEF, left ventricular outflow tract [LVOT] velocity, peak AV velocity).

During the chart review process, we specifically adjudicated whether AVR was performed, documenting the type of procedure (transcatheter aortic valve replacement [TAVR] or surgical aortic valve replacement [SAVR]) and the exact date of the procedure. Using the extracted clinical and demographic covariates, we calculated the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality score (STS PROM) for 30-day mortality. After physician adjudication of medical records, 83 eligible individuals were determined to have no symptoms at the time of the index TTE. Since inclusion of individuals from the era before TAVR became widely available was necessary to achieve adequate statistical power for studying this very narrow range of LVEF, our analysis includes individuals treated with both SAVR and TAVR.

Endpoints

The last follow-up, defined as the date of the last clinical encounter, was documented. Additionally, the date of death was recorded. All-cause mortality served as the primary outcome measure for the analysis. A subgroup analysis was conducted on asymptomatic individuals with severe high-gradient AS and an AVA of less than 0.9 cm², as well as those with very severe AS defined as an AVA of less than or equal to 0.75 cm². This subanalysis was conducted because these groups conceptually represent higher risk categories with increased hemodynamic burden and potentially worse clinical outcomes. Mortality data were collected by manually reviewing medical records. To ensure the accuracy of mortality data, confirmation was obtained through the MGB research patient data registry (RPDR), which integrates information from the Social Security Death Master File.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to examine the differences between individuals with asymptomatic high-gradient severe AS and an LVEF of of 50% to 54% who received AVR vs those who did not. Continuous variables were analyzed using independent samples t-tests and reported as means with SDs; categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square tests and presented as proportions.

Kaplan-Meier curves were used to investigate the survival outcomes, stratified by whether individuals in the entire cohort (AVA ≤ 1 cm²) underwent AVR, as well as in subgroups of individuals with an AVA of less than 0.9 cm² and an AVA of less than or equal to 0.75 cm². Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was conducted to generate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for survival. In order to mitigate potential immortal time bias, we incorporated a time-dependent covariate representing the duration from the index TTE to intervention. Immortal time bias occurs as a result of improper analysis that overestimates the treatment effect during a follow-up period in which the outcome is not possible. This bias arises because the period during which patients are “immortal” (ie, they must survive to receive the treatment/intervention) is not appropriately accounted for. To address this, individuals were initially categorized under conservative management (“watchful waiting”) until the intervention, at which point they were reassigned to the AVR group. Individuals who died before any intervention were assigned to the non-AVR group and those lost to follow up were censored at the last known follow-up. The time-dependent covariate was integrated into an extended Cox model. We investigated factors associated with mortality using univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models, adjusting for a time-dependent covariate as well as HTN, DM, CAD, TIA/stroke history, and serum creatinine levels to obtain an independent association of AVR with mortality.

P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical significance was determined by comparing variables stratified by AVR. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics version 28.0 (IBM) and R software version 4.3.1 (EZR; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing). The MGB Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective study and waived the requirement for informed patient consent.

Results

Patient characteristics

From January 1, 2000, to November 22, 2022, 1 232 492 TTEs were identified. Among these, 693 individuals had severe AS (AVA ≤1 cm2), an LVEF of 50% to 54%, and a mean AVG of greater than or equal to 40 mm Hg. After excluding individuals with symptomatic severe AS, those with prior AVR, and those lost to follow-up, 83 individuals were included in the analysis. Of these, 38 (45.8%) underwent AVR within 2 years of their index TTE, with 22 of them (58%) undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) and 16 (42%) undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). The mean time to AVR was 314 (± 200) days. Although all individuals were asymptomatic initially, 29 of the 38 patients who underwernt AVR (76.3%) were prompted by the development of symptoms in the meantime.

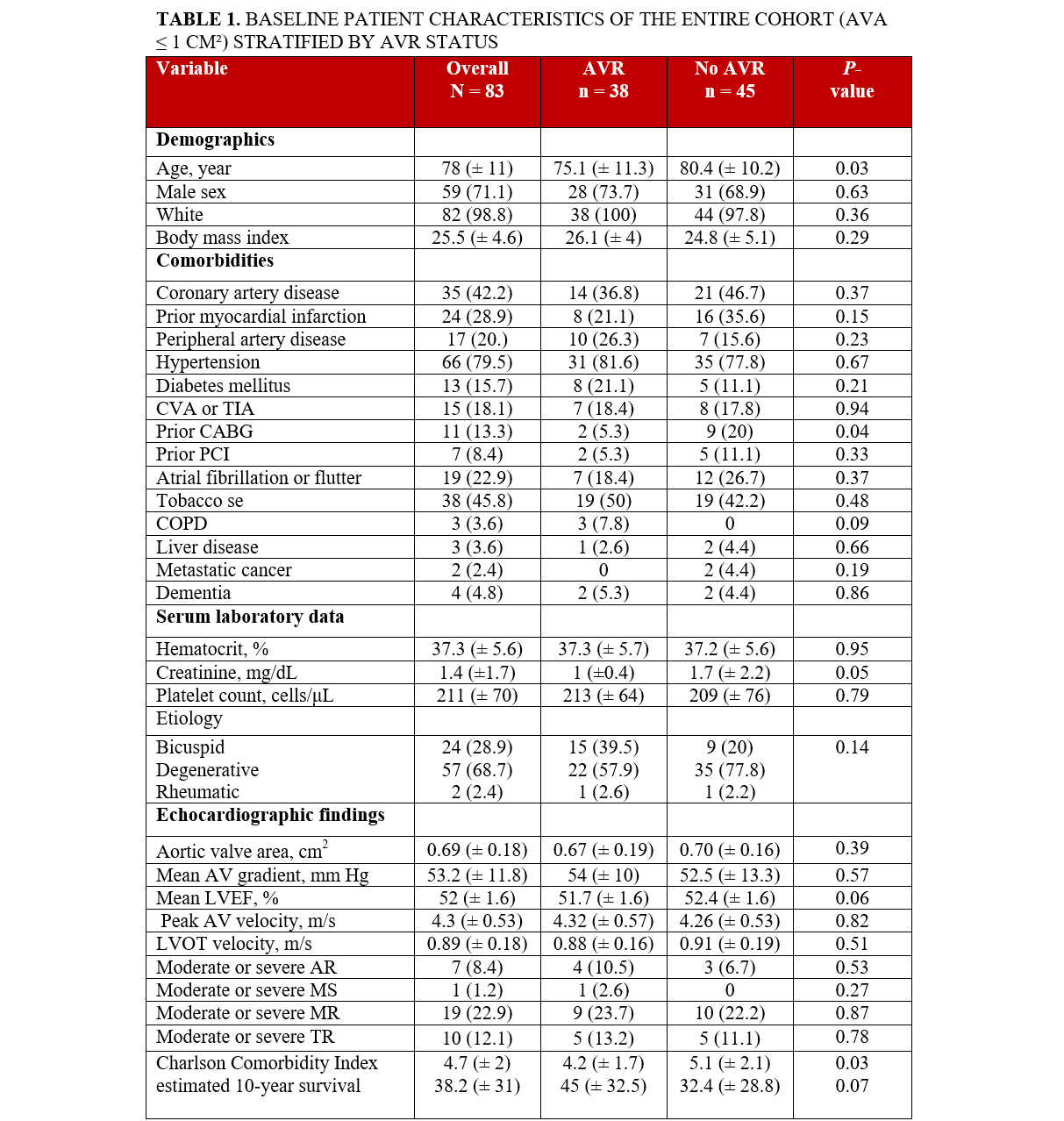

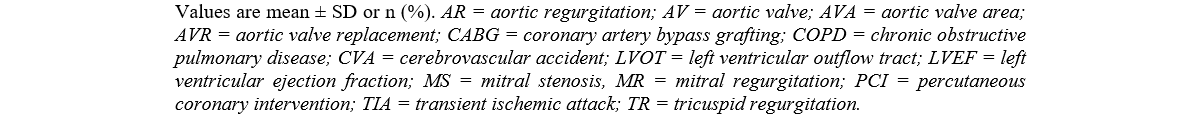

Individuals who underwent AVR were younger compared with those who did not undergo AVR, (75.1 vs 80.4; P = .03), with no significant differences noted in terms of race and gender between the 2 groups (Table 1). Those who underwent AVR were also less likely to have had a prior CABG compared with those who did not undergo AVR (5.3% vs 20%; P = .04). There were no other significant differences observed across other baseline comorbidities. Similarly, there were no significant differences in the etiology of severe AS or baseline laboratory findings. Echocardiographic results, including calculated AVA, LVEF, peak AV velocity, LVOT velocity, and other valvular pathology were similar between the groups (Table 1). AVR recipients had lower CCI scores (4.2 vs 5.1; P = .03). Additionally, AVR individuals had a lower risk of predicted operative mortality based on the STS PROM score (2.4 ± 2 vs 3.6 ± 3.2; P = .04) and a higher likelihood of a short hospital stay (48.0 ±19.1 vs 39.7 ±16.5; P = .04). No significant differences were noted in other predicted perioperative outcomes, including morbidity, mortality, stroke, renal failure, prolonged ventilation, deep sternal wound infection, or long hospital stay, according to the STS risk scores (Table 2).

Subgroup analysis (AVA < 0.9 cm²)

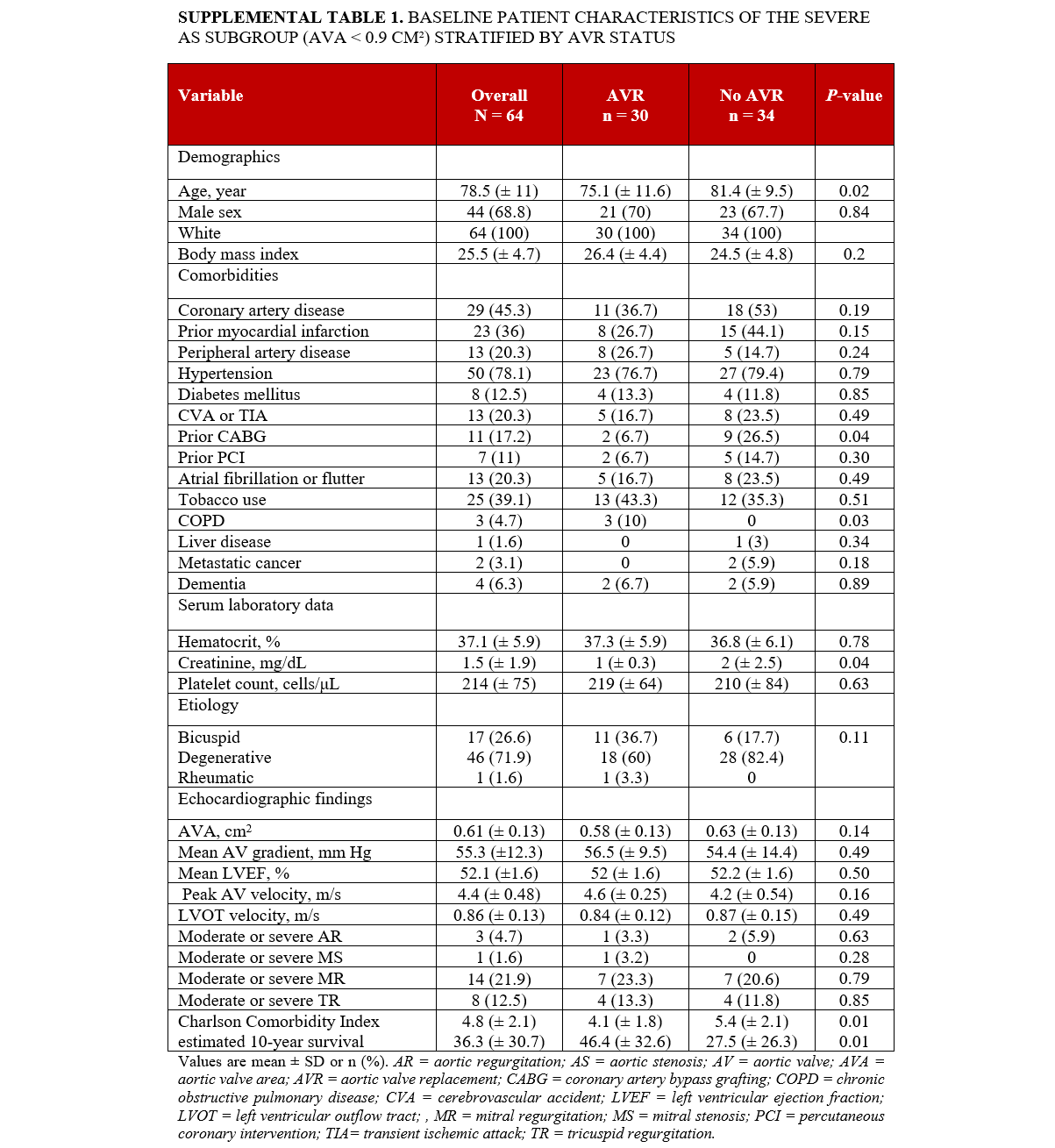

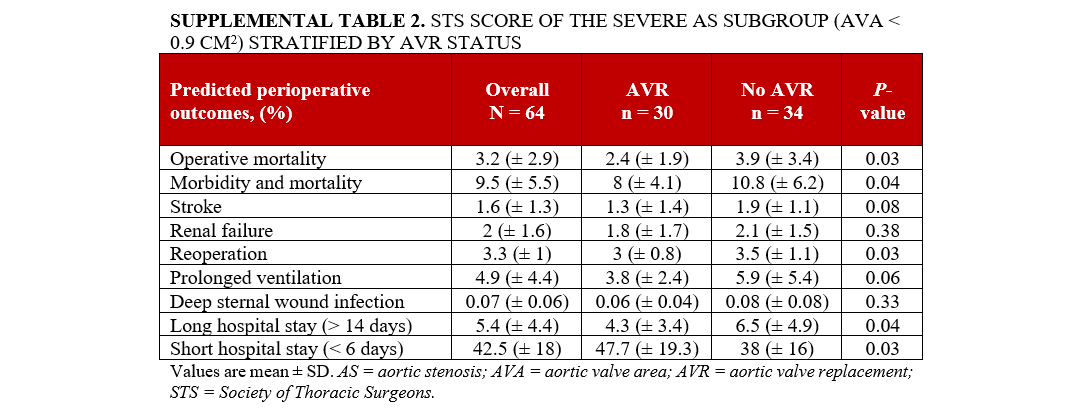

Supplemental Table 1 delineates the characteristics of the subgroup of individuals with severe AS with an AVA of less than 0.9 cm². A total of 64 patients were included in the analysis. Individuals in this subgroup who underwent AVR were younger compared with those who did not undergo AVR (75.1 ± 11.6 vs 81.4 ± 9.5; P = .02), with no significant differences in race and gender between the 2 groups. In terms of comorbidities, individuals who underwent AVR were less likely to have prior CABG (6.7% vs 26.5%; P = .04) and elevated creatinine (1.0 ± 0.3 vs 2.0 ± 2.5 mg/dL; P = .04). However, no significant differences were observed in other baseline comorbidities, AS etiology, other laboratory tests, or echocardiographic findings between the 2 groups (Supplemental Table 1). Individuals who underwent AVR had a lower CCI score (4.1 ± 1.8 vs 5.4 ± 2.1; P = .03) and a higher estimated 10-year survival rate (46.4% ± 32.6 vs 27.5% ± 26.3; P = .01) compared with individuals who did not undergo AVR. Additionally, individuals who underwent AVR had a reduced calculated risk of operative mortality (2.4 ± 1.9 vs 3.9 ± 3.4; P = .03), morbidity and mortality (8 ± 4.1 vs 10.8 ± 6.2; P = .04), reoperation (3 ± 0.8 vs 3.5 ± 1.1; P = .03), and long hospital stay (4.3 ± 3.4 vs 6.5 ± 4.9; P = .04), alongside a higher likelihood of a short hospital stay (47.7 ± 19.3 vs 38 ± 16; P = .03) according to STS short-term/operative risk scores (Supplemental Table 2). Factors associated with mortality in the severe AS subgroup (AVA < 0.9 cm²) are presented in Supplemental Table S3.

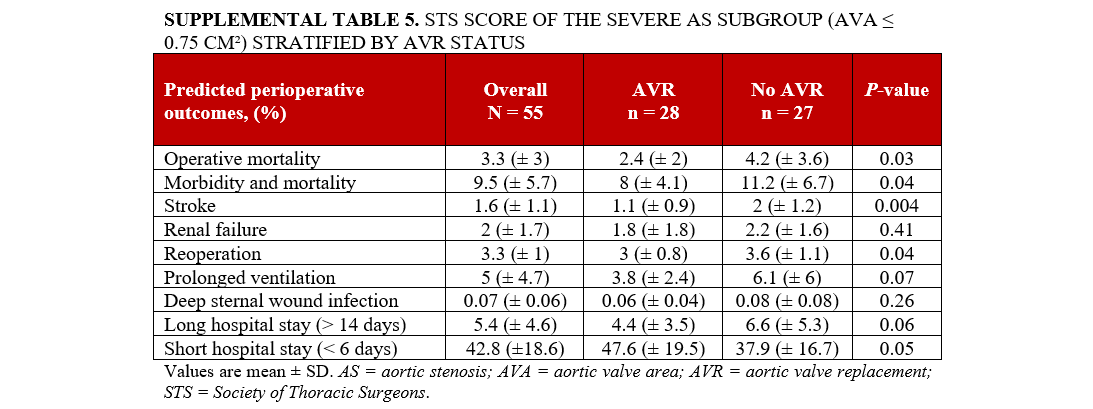

Subgroup analysis (AVA ≤ 0.75 cm²)

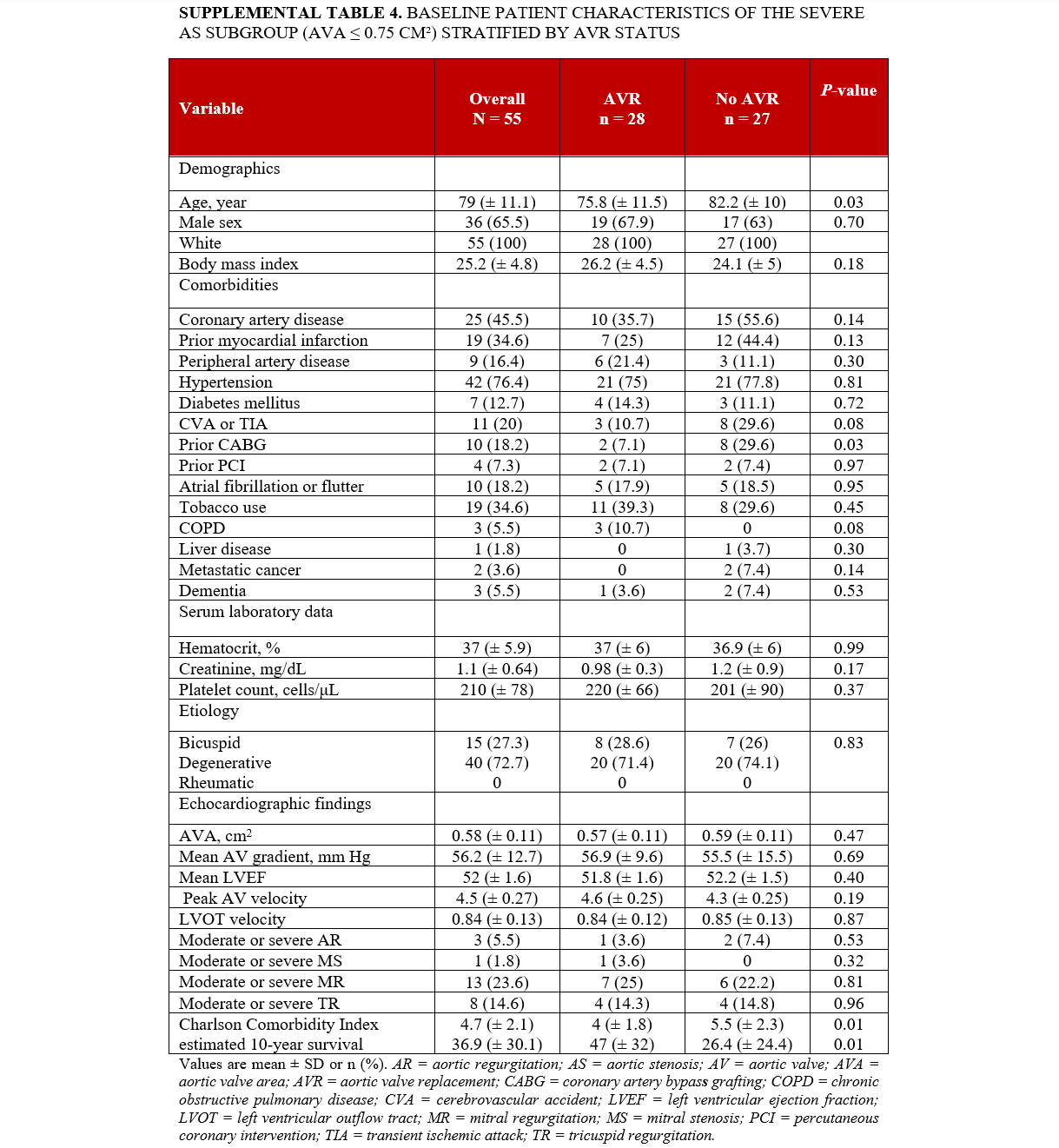

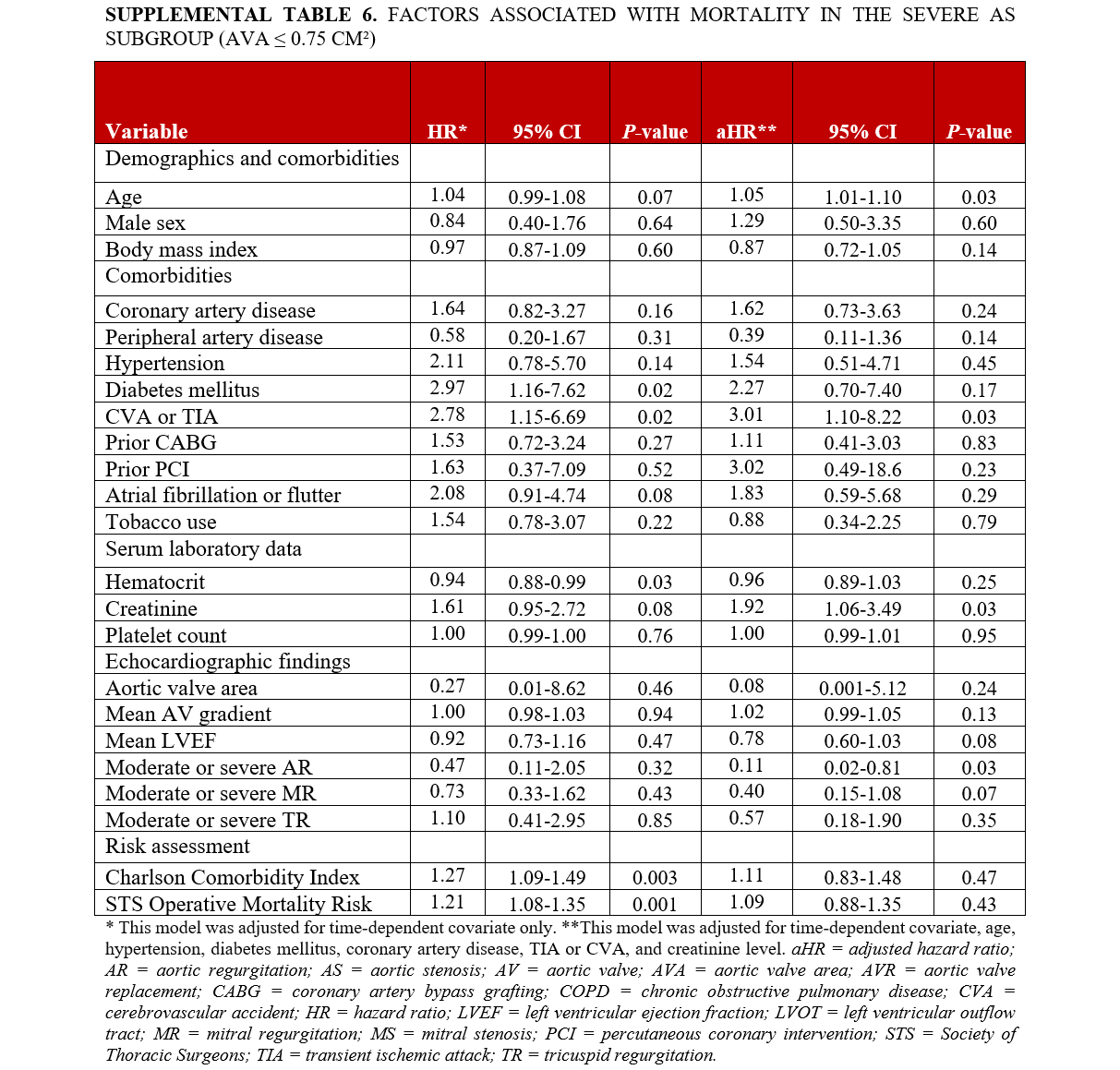

Supplemental Table 4 outlines the characteristics of the subgroup of individuals with severe AS with AVA < 0.75 cm². The analysis included a total of 55 patients. In this subgroup, those who underwent AVR were younger (75.8 ± 11.5 years) compared to those who did not (82.2 ± 10 years; P = .03), with no significant differences in race and gender between the 2 groups. Individuals who underwent AVR were less likely to have a history of prior CABG (7.1% vs 29.6%; P = .03). No significant differences were observed in other baseline comorbidities, AS etiology, other laboratory tests, or echocardiographic findings. Individuals who underwent AVR had a lower CCI score (4 ± 1.8 vs 5.5 ± 2.3; P = .009) and a higher estimated 10-year survival rate (47% ± 32 vs. 26% ± 24; P = .01) compared with individuals who did not undergo AVR. Additionally, individuals who underwent AVR had a lower calculated risk of operative mortality (2.4 ± 2 vs 4.2 ± 3.6; P = .03), morbidity and mortality (8 ± 4.1 vs 11.2 ± 6.7; P = .04), stroke (1.1 ± 0.9 vs 2 ± 1.2; P = .004), reoperation (3 ± 0.8 vs 3.6 ± 1.1; P = .04), and a shorter hospital stay (47.6 ± 19.5 vs 37.9 ± 16.7 days; P = .05) according to STS short-term/operative risk scores (Supplemental Table 5). Factors associated with mortality in the severe AS subgroup (AVA < 0.75 cm²) are presented in Supplemental Table S6.

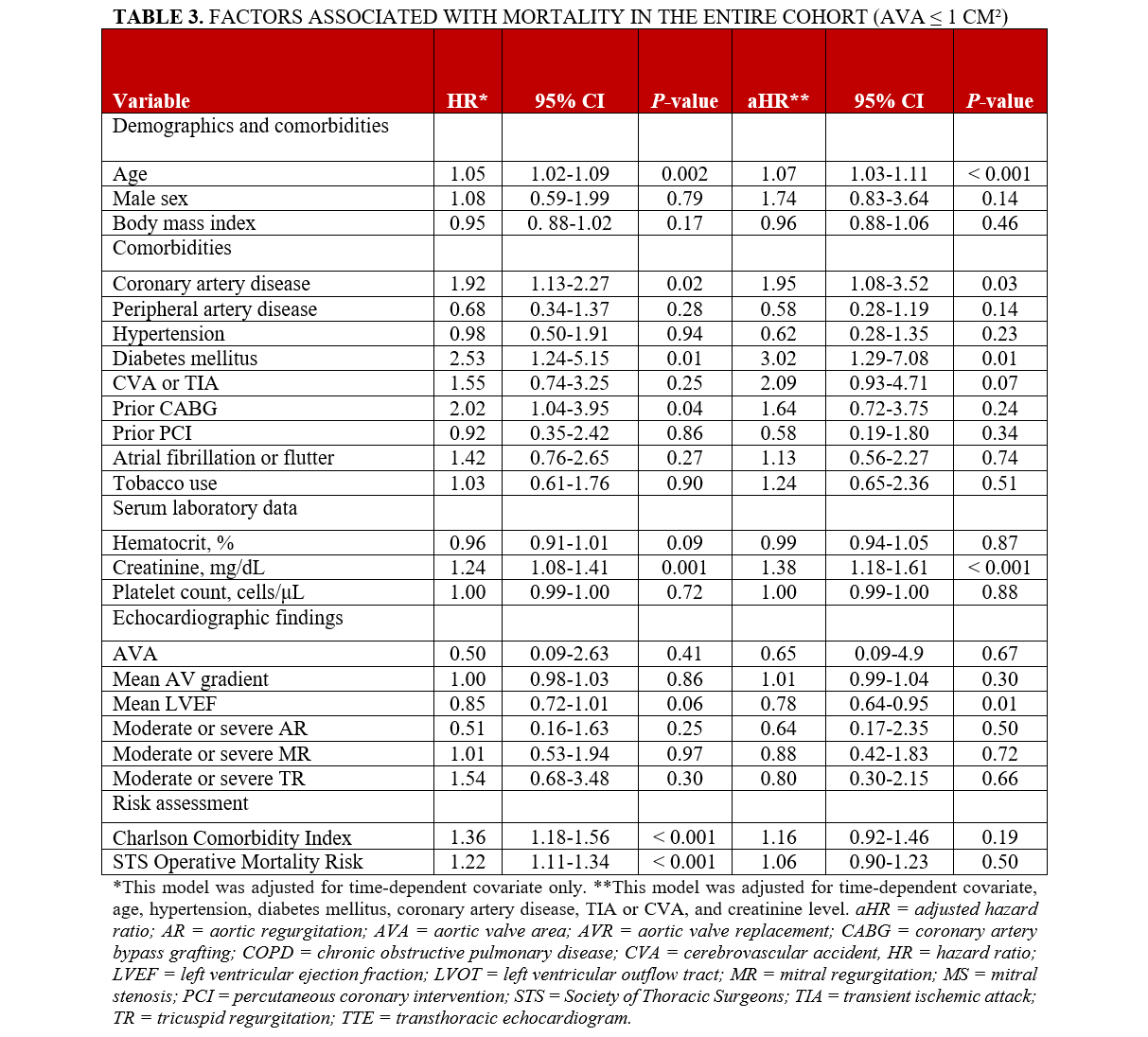

Factors associated with mortality

The study identified several independent factors associated with higher mortality. These factors included older age (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.03-1.11; P < .001), history of CAD (adjusted [a] HR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.08-3.52; P < .03), DM (aHR, 3.02; 95% CI, 1.29-7.08; P < .01), higher creatinine levels (aHR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.18-1.61; P < .001), and lower mean LVEF (aHR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.64-0.95; P = .01) (Table 3).

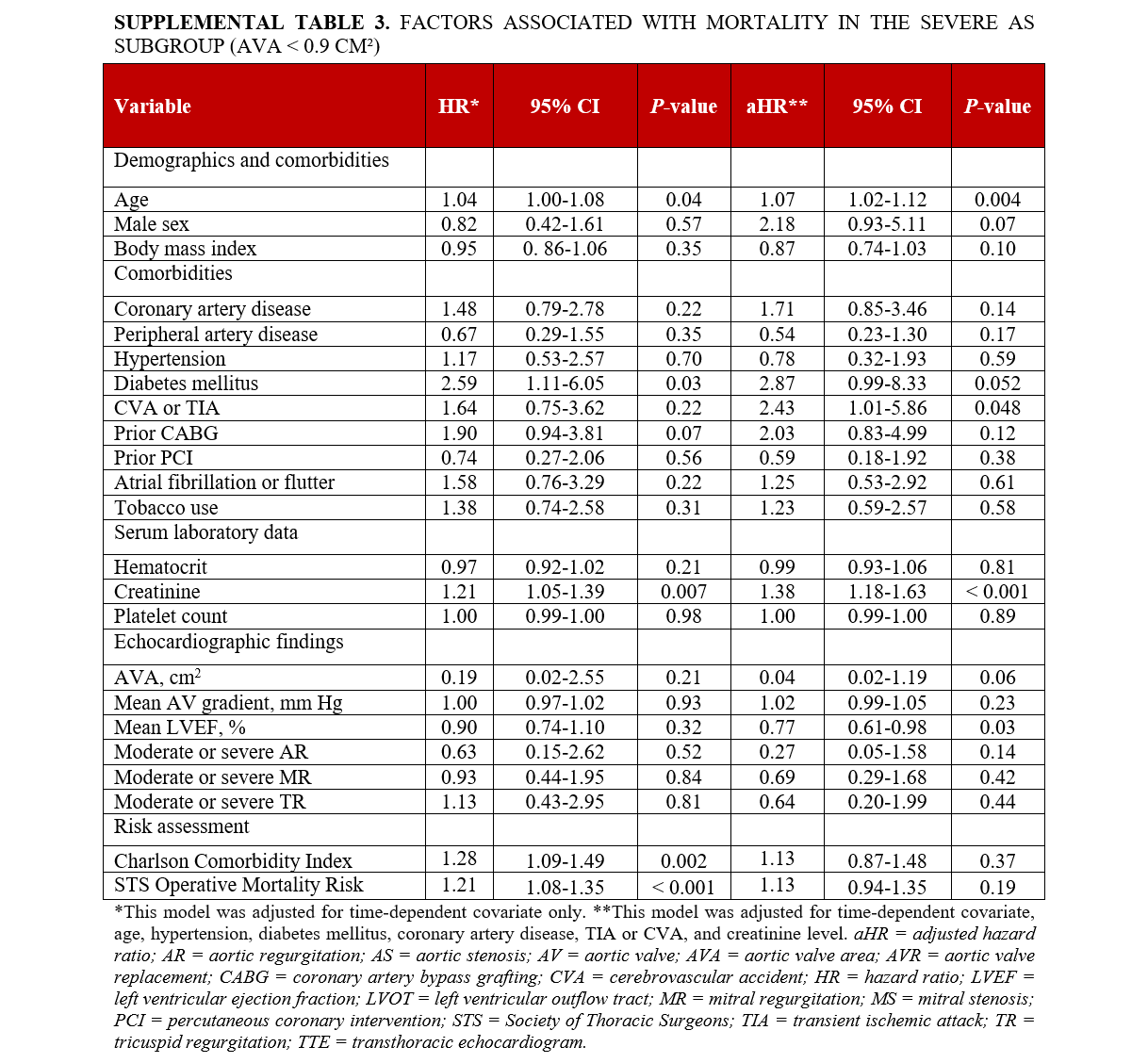

In individuals with an AVA of less than 0.9 cm², older age (aHR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.12; P = .004), a history of TIA/CVA (aHR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.01-5.86; P < .04), higher creatinine levels (aHR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.18-1.63; P < .001), and lower LVEF (aHR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.61-0.98; P = .03) were associated with increased mortality. Furthermore, among those with an even smaller AVA (≤ 0.75 cm²), advanced age (aHR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.10; P = .03), a history of TIA/CVA (aHR, 3.01; 95% CI, 1.10-8.22; P = .03), and higher creatinine levels (aHR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.06-3.49; P = .03) were independently associated with a higher likelihood of mortality.

Survival analysis

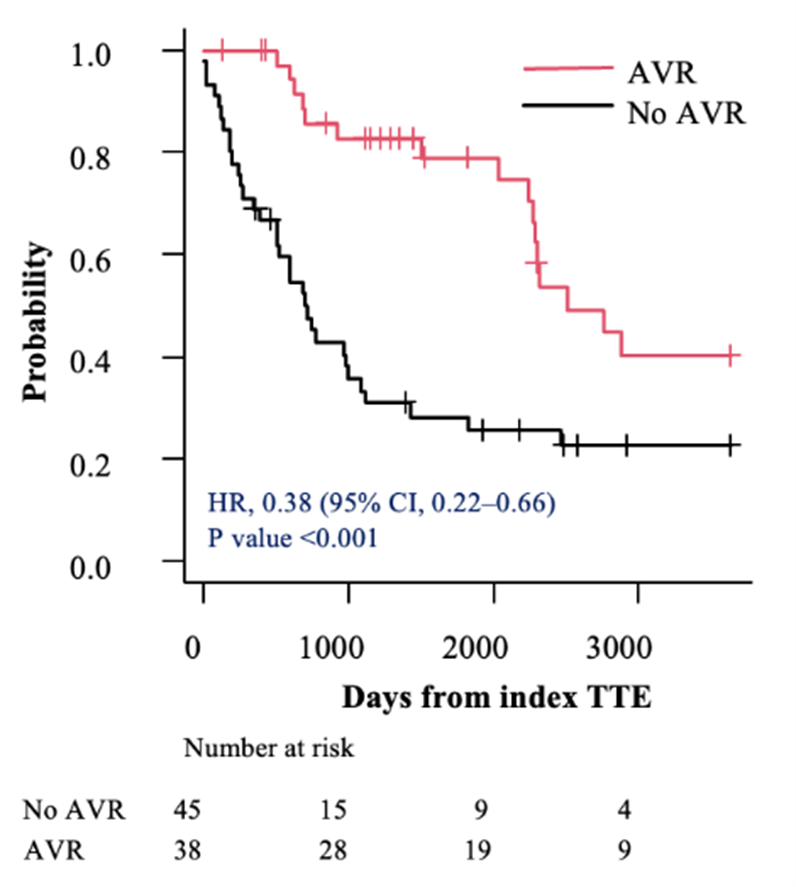

Before accounting for immortal time, all individuals with severe asymptomatic AS (AVA< 1.0 cm2) and an LVEF of 50% to 54% who underwent AVR within 2 years of their index TTE had lower mortality compared with those treated conservatively (HR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.22-0.66; P < .001) (Figure 2A). After adjusting for the index TTE to AVR as a time-dependent covariate, the HR was of only borderline significance (HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.31-1.01; P = .054 (Figure 2B).

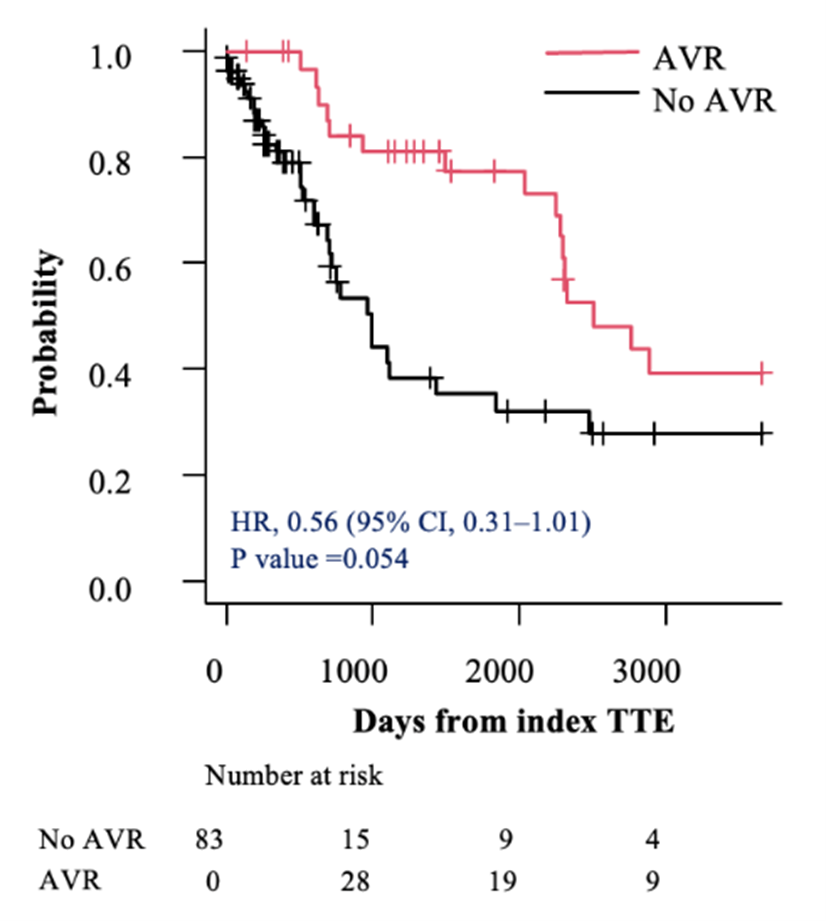

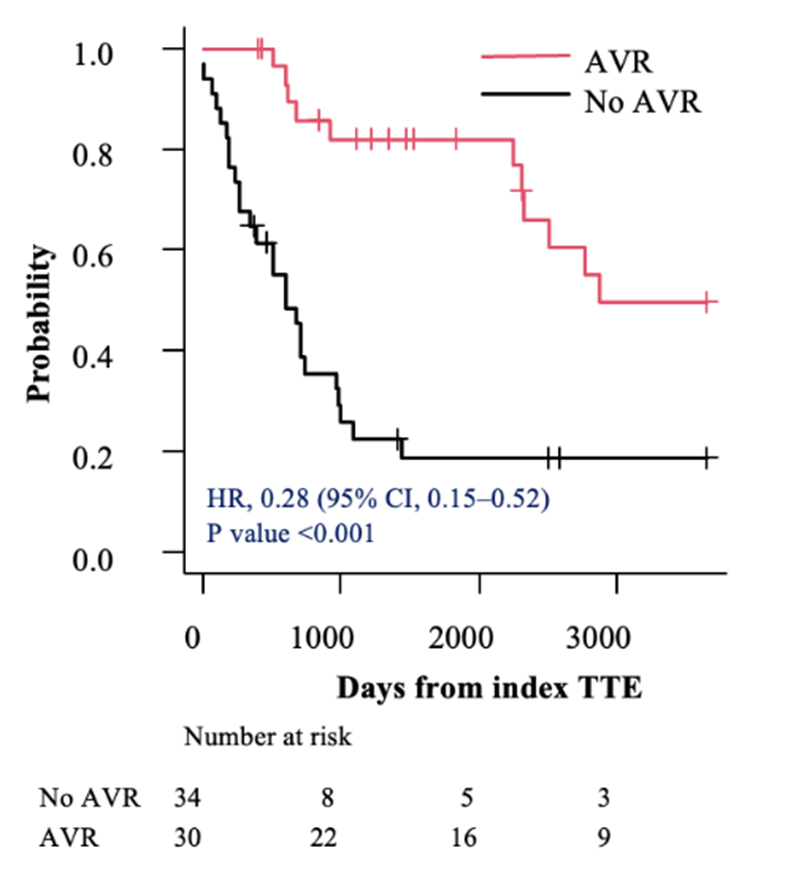

In the subsets of individuals with severe AS (AVA < 0.9 cm²) and very severe AS (AVA ≤ 0.75 cm²), AVR was associated with a lower hazard of mortality compared with those who did not undergo AVR (HR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.15-0.52; P < .001 vs HR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.09-0.43; P < .001, respectively) (Figures 3A and 4A). This survival benefit persisted even after incorporating the time elapsed from the index TTE to the AVR as a time-dependent covariate (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.21-0.84; P = .01 vs HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.15-0.75; P = .008, respectively) (Figures 3B and 4B).

Discussion

In this work, we have shown that, even within this small sample required to assess this narrow LVEF range, AVR is associated with improved survival among initially asymptomatic individuals with an AVA of less than 0.9 cm2. Although the result was not quite statistically significant, in additional analyses, there was also a trend toward improved survival in this LVEF range for all individuals with severe AS up through an AVA of 1.0 cm2. This mortality advantage in the subsets more severe AS suggests a “dose-dependent” relationship. Taken together, these results suggest that a mortality advantage is likely even among the broader population with an AVA of less than or equal to 1.0 cm2.

The optimal timing for AVR in asymptomatic individuals with severe AS with an LVEF of 50% to 54% remains uncertain, with divergent recommendations and LVEF thresholds in European and American guidelines.5-7 Previous research has shown increased mortality risks in asymptomatic patients with AS with an LVEF of greater than 60%.21,22 While randomized clinical trials have endorsed an early AVR strategy in asymptomatic severe AS by showing a reduction in all-cause mortality, these trials did not specifically target individuals within the 50%-to-54% LVEF range.10-12 Notably, these trial included individuals with higher mean or median LVEFs, potentially limiting the generalizability of their findings to this patient population with an LVEF of 50% to 54%. Moreover, the different enrollment criteria of previous trials, such as the requirement for very severe AS in the RECOVERY trial or the exclusion of individuals at high surgical risk in the AVATAR and EARLY TAVR trials, limit the ability of these results to inform this specific clinical situation.10,11 Given the implausibility of conducting trials specific to asymptomatic individuals with severe AS with high gradient and an LVEF of 50% to 54%, our study provides more support for the higher LVEF threshold (55%) used in European guidelines, particularly in more severe forms of AS.

Forthcoming trials are likely to provide additional information regarding which individuals should receive AVR in severe AS, even without symptoms. For example, the EASY AS-trial is assessing differences in mortality or heart failure hospitalization among all individuals with severe asymptomatic AS, even with a Vmax down to 4.0 m/sec and an LVEF of greater than equal to 50%.23 The DANAVR trial will include some individuals with normal systolic function but markers of diastolic dysfunction, such as left atrial enlargement, abnormal E/e’ ratio, or elevated N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in the setting of normal systolic function.24 The EVOLVED trial will include individuals with mid-wall late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.25 These trial results should provide much more information that will allow the integration of clinical and imaging data to customize treatment approaches to asymptomatic severe AS.

Although trials are ideal for determining treatment effects and many trials of AVR have been performed, they are often underpowered to detect heterogeneous treatment effects in small populations. To address the treatment decision in this small population with a narrow LVEF range of 50% to 54%, we had to query a large echocardiography registry of over 1 million echocardiograms to detect sufficient numbers of individuals to study. However, as predicted in this analysis of observational data, the individuals chosen for AVR were better surgical candidates. For example, those who underwent AVR demonstrated a lower burden of comorbidities, as reflected in their lower CCI scores. In our study, the CCI score averaged 4.2 (± 1.7) in the AVR group. In addition, individuals who received AVR had substantially lower STS-PROM scores, with a mean operative mortality risk of 2.4% (± 2). To mitigate potential biases stemming from these case mix differences, we incorporated relevant clinical variables into extended Cox models. Although all individuals were initially asymptomatic, about three-quarters of those who eventually received AVR developed symptoms later, prompting AVR.

In this observational dataset with retrospective analysis, we also addressed immortal time bias. This bias can occur in retrospective analyses of observational data when individuals who die before they can be considered for or receive AVR are systematically allocated to the “medical management” group. Such misclassification can lead to an overestimation of treatment effects. To address this, we treated AVR as a time-dependent covariate. This approach essentially allows a given individual to “count” for “medical management” before AVR but then “count” for AVR after the replacement. This method offsets the bias of systematic allocation of those who die early to the “no AVR” group. We have previously shown that failure to consider procedures or surgeries as time-dependent covariates can cause overestimation of treatment effects.13,14

Even when time-varying covariates are used, the reduction in mortality among those with an AVA of less than 0.9 cm² as well as an AVA of less than or equal to 0.75 cm² persists. These findings, along with the overall finding of borderline significance observed among all individuals with high-gradient severe AS but without symptoms, raise concerns about withholding AVR for those individuals, as it may increase mortality. This concern arises from the possibility that the incidence of sudden death among asymptomatic individuals with severe AS may be higher than previously reported in prior studies.26 Additionally, delays in patients reporting symptoms promptly as well as the anticipated higher risk of operative mortality in symptomatic patients with severe AS highlight the critical need for careful clinical decision making.

These findings have important implications for clinical practice, emphasizing the need for close monitoring when considering conservative management strategies for asymptomatic individuals with severe AS with an LVEF of 50% to 54%. AVR within 2 years of index TTE appears to offer significant benefits in selected individuals with more severe AS who were asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. Clinicians should carefully weigh the risks and benefits of early intervention, taking into account disease severity and individual patient characteristics. Although trials could potentially provide more information, they are unlikely to ever be performed with adequate statistical power for this specific population.

Limitations

Our study must be interpreted in the setting of several limitations. First, this research is a retrospective analysis. Second, the use of NLP for data extraction might create errors; nevertheless, to mitigate this risk, a manual chart review was conducted. Third, our study cohort consisted only of individuals from 7 hospitals within a single health care setting; therefore, the results may not be generalizable to all practice settings. Moreover, the sample size of our study may have led to the negative finding of borderline statistical significance in the main analysis. Time-varying covariates are statistically inefficient but important for avoiding immortal time bias. Fourth, although we performed systematic physician chart review to determine asymptomatic status, we cannot determine if individuals had symptoms that were underrecognized or underreported, nor can we assess whether symptom detection was comparable across subjects. This could be addressed in a trial framework with systematic stress testing, but is not feasible with retrospective analysis of observational data. Fifth, we did not have enough statistical power to conduct subgroup analyses on individuals with TAVR alone. Finally, inconsistencies in echocardiogram interpretation across the 7 hospitals and the absence of direct image adjudication for echocardiographic data could have introduced variability in data accuracy.

Conclusions

Among initially asymptomatic individuals with severe high-gradient AS and an LVEF of 50% to 54%, our study demonstrated that AVR was associated with significantly improved survival, particularly in cases with high-grade severe AS. Guidelines should consider a more inclusive LVEF threshold for recommending AVR in cases of asymptomatic severe AS, especially for those with advanced disease.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Muhammad Etiwy, MD1,2; Adam N. Berman, MD, MPH3; Michael H. Picard, MD2; Chiara Fraccaro, MD, PhD4; Nicole Karam, MD, PhD5; Meagan M. Wasfy, MD, MPH2; Yunong Zhao, MS6; Magdi Zordok, MD7; John Hsu, MD, MBA, MSCE6,8; Jason H. Wasfy, MD, MPhil2,6

From the 1Department of Medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, New Hampshire; 2Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; 3Leon H. Charney Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, New York; 4Department of Cardiac, Thoracic, Vascular Sciences and Public Health, University of Padova, Padova, Italy; 5Department of Cardiology, European Hospital Georges Pompidou, Paris, France; 6Mongan Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; 7Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Baylor Scott and White, Plano, Texas; 8Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

Disclosures: Dr Fraccaro has received minor lecture fees from Edwards Lifesciences. Dr Karam serves as a consultant for Edwards, Medtronic, and Abbott. Dr Wasfy is supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R56HL171144). The remaining authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Funding: This work was in part supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R56HL171144) and the Massachusetts General Hospital Executive Committee on Research (24-1) awarded to Dr. Wasfy, as well as the generous support of the Clem family.

Address for correspondence: Jason H. Wasfy, MD, MPhil, Mass General Brigham Heart and Vascular Institute, 55 Fruit St, Boston, MA 02114, USA. Email: jwasfy@mgh.harvard.edu; X: @jasonwasfy

References

1. Yadgir S, Johnson CO, Aboyans V, et al; Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 Nonrheumatic Valve Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of calcific aortic valve and degenerative mitral valve diseases, 1990-2017. Circulation. 2020;141(21):1670-1680. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043391

2. Tung M, Nah G, Tang J, Marcus G, Delling FN. Valvular disease burden in the modern era of percutaneous and surgical interventions: the UK Biobank. Open Heart. 2022;9(2):e002039. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2022-002039

3. Tang L, Gössl M, Ahmed A, et al. Contemporary reasons and clinical outcomes for patients with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis not undergoing aortic valve replacement. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(12):e007220. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.007220

4. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(17):1597-1607. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1008232

5. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143(5):e72-e227. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

6. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al; ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(7):561-632. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395

7. Praz F, Borger MA, Lanz J, et al; ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group. 2025 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2025;46(44):4635-4736. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf194

8. Hillis GS, McCann GP, Newby DE. Is asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis still a waiting game? Circulation. 2022;145(12):874-876. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.058598

9. B Bohbot Y, de Meester de Ravenstein C, Chadha G, et al. Relationship between left ventricular ejection fraction and mortality in asymptomatic and minimally symptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(1):38-48. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.07.029

10. Kang DH, Park SJ, Lee SA, et al. Early surgery or conservative care for asymptomatic aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(2):111-119. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1912846

11. Banovic M, Putnik S, Penicka M, et al; AVATAR Trial Investigators*. Aortic valve replacement versus conservative treatment in asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis: the AVATAR trial. Circulation. 2022;145(9):648-658. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.057639

12. Généreux P, Schwartz A, Oldemeyer JB, et al; EARLY TAVR Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement for asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(3):217-227. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2405880

13. Axtell AL, Bhambhani V, Moonsamy P, et al. Surgery does not improve survival in patients with isolated severe tricuspid regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(6):715-725. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.04.028

14. Wasfy JH, Achanta A, Hidrue MK, et al. Association between implanted cardioverter-defibrillators and mortality for patients with left ventricular ejection fraction between 30% and 35. Open Heart. 2023;10(2):e002289. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2023-002289

15. Malmasi S, Sandor NL, Hosomura N, Goldberg M, Skentzos S, Turchin A. Canary: an NLP platform for clinicians and researchers. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;8(2):447-453. doi:10.4338/ACI-2017-01-IE-0018

16. Berman AN, Ginder C, Sporn ZA, et al. Natural language processing for the ascertainment and phenotyping of left ventricular hypertrophy and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy on echocardiogram reports. Am J Cardiol. 2023;206:247-253. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2023.08.109

17. Etiwy M, Flannery LD, Li SX, et al. Examining lack of referrals to heart valve specialists as mechanisms of potential underutilization of aortic valve replacement. Am Heart J. 2024;274:54-64. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2024.04.006

18. Li SX, Patel NK, Flannery LD, et al. Trends in utilization of aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(9):864-877. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.11.060

19. Dong T, Sunderland N, Nightingale A, et al. Development and evaluation of a natural language processing system for curating a trans-thoracic echocardiogram (TTE) database. Bioengineering (Basel). 2023;10(11):1307. doi:10.3390/bioengineering10111307

20. Nath C, Albaghdadi MS, Jonnalagadda SR. A natural language processing tool for large-scale data extraction from echocardiography reports. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153749. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153749

21. Lancellotti P, Magne J, Dulgheru R, et al. Outcomes of patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis followed up in heart valve clinics. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(11):1060-1068. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3152

22. Taniguchi T, Morimoto T, Shiomi H, et al; CURRENT AS Registry Investigators. Prognostic impact of left ventricular ejection fraction in patients with severe aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(2):145-157. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2017.08.036

23. Richardson C, Gilbert T, Aslam S, et al. Rationale and design of the early valve replacement in severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis trial. Am Heart J. 2024;275:119-127. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2024.05.013

24. The Early Valve Replacement in Severe ASYmptomatic Aortic Stenosis Study (EASY-AS). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04204915. Updated September 25, 2025. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04204915

25. Bing R, Everett RJ, Tuck C, et al. Rationale and design of the randomized, controlled Early Valve Replacement Guided by Biomarkers of Left Ventricular Decompensation in Asymptomatic Patients with Severe Aortic Stenosis (EVOLVED) trial. Am Heart J. 2019;212:91-100. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2019.02.018

26. Taniguchi T, Morimoto T, Shiomi H, et al; CURRENT AS Registry Investigators. Sudden death in patients with severe aortic stenosis: observations from the CURRENT AS registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(11):e008397. doi:10.1161/JAHA.117.008397