Early Outcomes of Facilitated Transfemoral Versus Alternative Access for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2026. doi:10.25270/jic/25.00171. Epub January 8, 2026.

Abstract

Objectives. Transfemoral (TF) access for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) may be challenging in patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD). Alternative access through intra- and extrathoracic approaches can be performed. Recently, a facilitated TF access strategy, which involves the use of intravascular lithotripsy to optimize the iliofemoral arteries prior to TAVR, has been utilized. The aim of this study was to evaluate early outcomes of facilitated TF access compared to alternative access in patients with severe PAD.

Methods. Patients with severe PAD who underwent TAVR from 2021 to 2023 were included in the study and were divided into 2 groups: facilitated and alternative access. The primary endpoint was a composite of mortality, stroke, and vascular complications. Mortality was evaluated in-hospital and at 1-month follow-up.

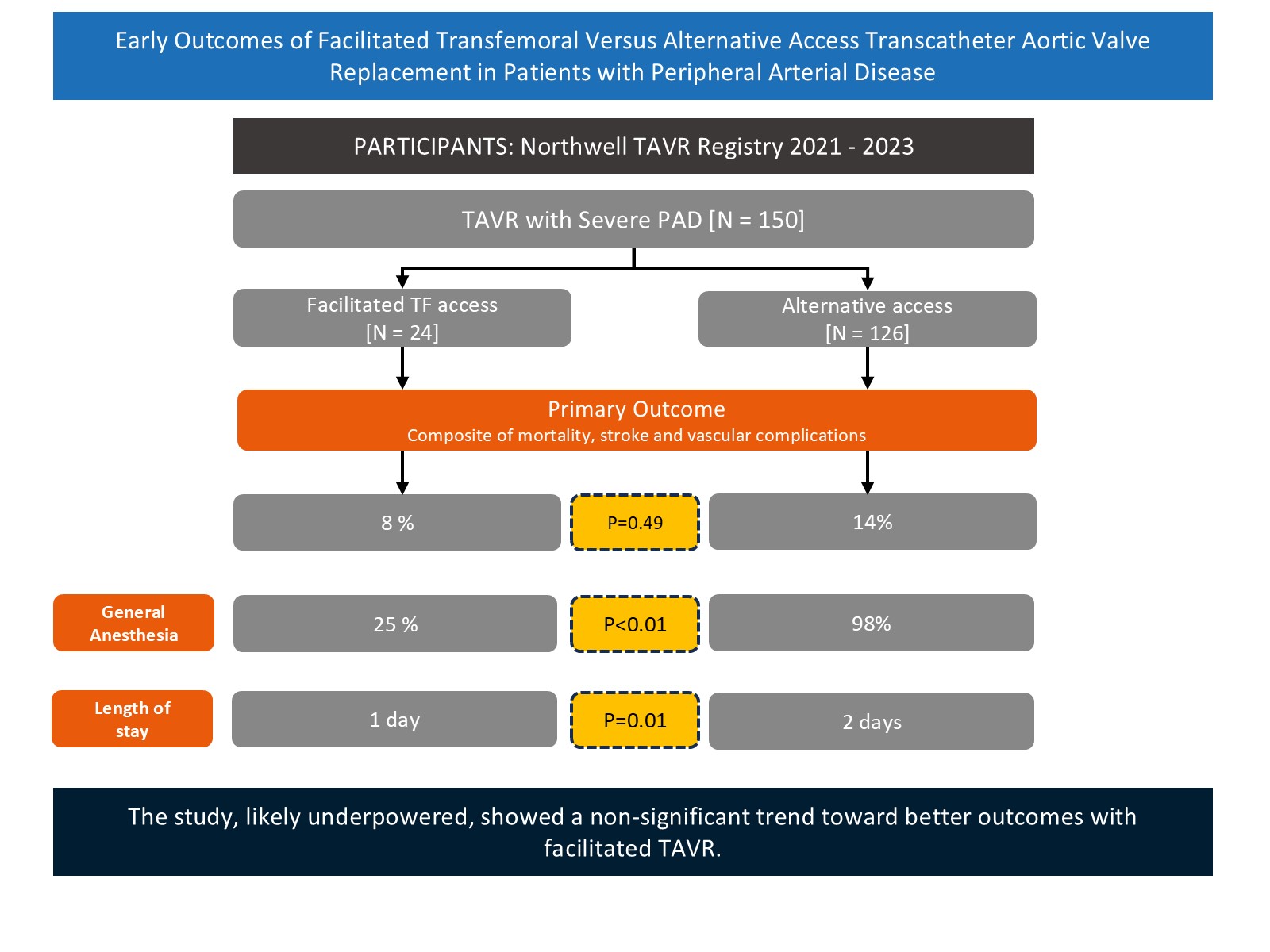

Results. Of 150 TAVR patients with severe PAD, 24 underwent facilitated access. Baseline characteristics including age, Society of Thoracic Surgeons score, and mean gradients were similar between the 2 groups. The most common alternative access was transsubclavian, followed by transcarotid. Primary outcomes were numerically higher in the alternative access group (14% vs 8%); however, this did not reach statistical significance (P = .49). General anesthesia use and postoperative length of stay were higher in the alternative access group. Postoperative and 1-month mortalities were similar between the 2 groups.

Conclusions. Although the primary endpoint did not reach statistical significance, the numerical trend toward better outcomes in the facilitated TAVR group indicates a potential advantage. Large-scale prospective studies are required to determine the appropriate access strategy for TAVR in patients with severe PAD.

Introduction

Over the past decade, transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has emerged as an alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) and its utilization has now surpassed SAVR in the United States.1 This shift has been driven in part by the expanded approval for low and intermediate risk.2 Access routes for TAVR include transfemoral (TF) or alternative access approaches.3,4 Among these, the TF approach is the most common, with 95.3% of TAVR cases in the United States performed via TF access.5,6

When TF access is compromised, such as in patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD), small vessel caliber, tortuous anatomy, or prior iliofemoral interventions, alternative access routes must be considered.7 PAD is a frequent comorbidity that affects 25% of TAVR patients and is particularly concerning, as severe PAD increases the risk of major vascular complications and procedural bleeding, and also limits the use of certain vascular closure devices post-TAVR.1,7-9 Once widely used, the intrathoracic approaches (transapical and direct aortic) are now largely of historical interest because of their higher rates of complications, morbidity, and mortality, while extrathoracic alternative access strategies have gained wider acceptance.1 These include transaxillary/subclavian, transinnominate, transcarotid, and transcaval approaches. Recent expert consensus suggests that, when anatomically feasible, transcarotid and transcaval access are preferred to transaxillary access, with transcarotid access being the most used alternative access site in North America.6

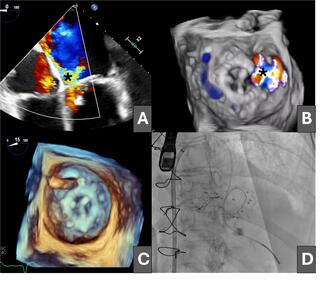

More recently, a facilitated TF access strategy using intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) has been increasingly utilized in patients with severe symptomatic lower extremity PAD. This approach involves the use of IVL to fracture intimal and medial vessel calcifications, increasing vessel compliance and enabling the passage of sheaths and valve delivery systems through the femoral artery. This novel TAVR approach has enabled the use of the TF route even when femoral access was previously considered unsuitable.10-12 Limited studies have evaluated the outcomes of IVL-facilitated TF TAVR when compared to conventional alternative access TAVR. The purpose of this study was to compare the early outcomes and safety of IVL-facilitated TF access with conventional alternative access strategies in TAVR patients with severe PAD.

Methods

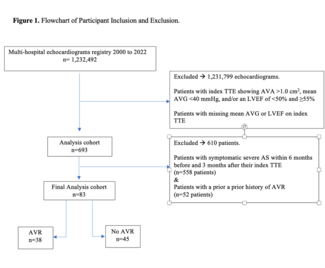

Data was collected from the Northwell TAVR registry, a prospectively maintained mandatory database at 4 high-volume TAVR/transcatheter edge-to-edge repair centers within the Northwell Health system. A total of 150 TAVR patients with severe PAD who underwent TAVR from 2021 to 2023 were included in the study. Study data was collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies hosted at Northwell Health. The study received Northwell Institutional Review Board approval along with a waiver of informed consent. The study adhered to all relevant ethical guidelines and principles.

The included patients with severe PAD were divided into 2 groups: facilitated TF and alternative access. All included patients underwent contrast‐enhanced multidetector computed tomography, including the evaluation of iliac and femoral arteries. Patients were then scheduled to either undergo facilitated TF access TAVR or alternative access TAVR. Facilitated access involved the use of IVL in cases of suboptimal iliofemoral access prior to TAVR. The site of alternative access was at the discretion of the operator.

Baseline demographics and comorbidities were collected. Demographic characteristics included age, gender, and body mass index. Comorbidities included smoking, chronic lung disease, hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, carotid artery stenosis, myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED), stroke, Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) score, left ventricular ejection fraction, and balloon-expandable valves. The HOSTILE score, a surrogate for complexity of iliofemoral disease, was also calculated.

The primary endpoint was a composite of mortality, stroke, and vascular complications at discharge. Vascular complications were defined as the presence of a major or minor vascular complication. Mortality and stroke were also evaluated at discharge and at 1 month. All clinical endpoints were defined according to the Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC)-3 definitions.13 Other outcomes evaluated at discharge included unplanned vascular intervention, access-site hematoma, CIED, device embolization, blood transfusion, general anesthesia, and postoperative length of stay (LOS). Unplanned vascular intervention was defined as any access site procedure required for hemostasis, including covered stent placement or vascular cutdown.

Categorical variables are presented as counts and/or percentages and were compared using the chi-square statistic or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± SD and were compared using the Student’s t‐test or presented as mean [lower quartile, upper quartile] and were compared using the Mann-Whitney test as appropriate. A P-value of less than or equal to 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were 2‐tailed and performed using Prism 9.4.0 (GraphPad Software).

Results

A total of 150 patients with severe PAD who underwent TAVR between 2021 and 2023 were included in the analysis. Of these, 24 patients (16%) underwent facilitated TF access TAVR, while the remaining 126 (84%) underwent alternative access TAVR.

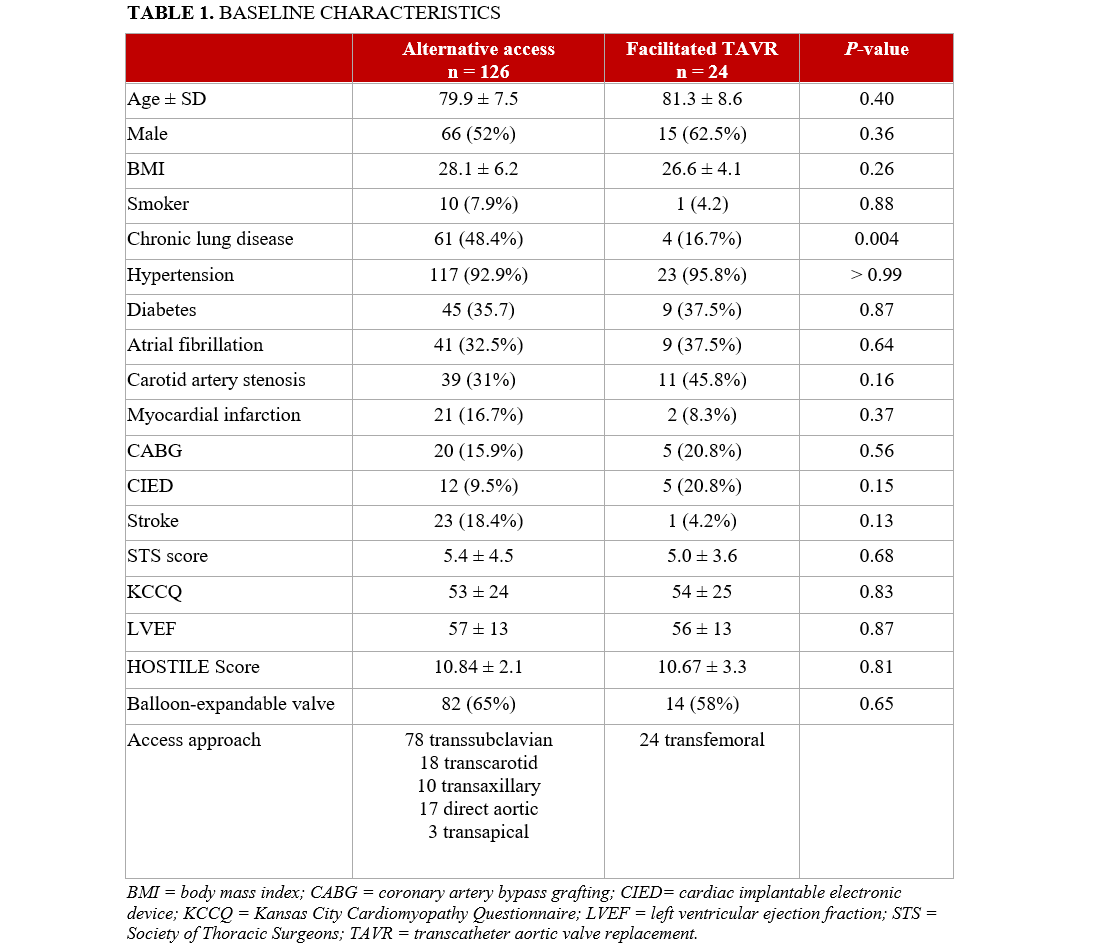

Baseline characteristics, including age, STS score, HOSTILE score, and mean transvalvular gradients, were comparable between the 2 groups; the exception was a higher prevalence of chronic lung disease in the alternative access group (48.4% vs 16.7%; P = .004) (Table 1). The mean STS score for the overall cohort was 5.2%. The mean HOSTILE score was 10.7 (median 11.5) and was comparable between the alternative access and facilitated TF access groups (10.8 vs 10.7, respectively). Among patients who underwent alternative access, the subclavian artery was the most frequently used site, followed by the carotid artery (Table 1).

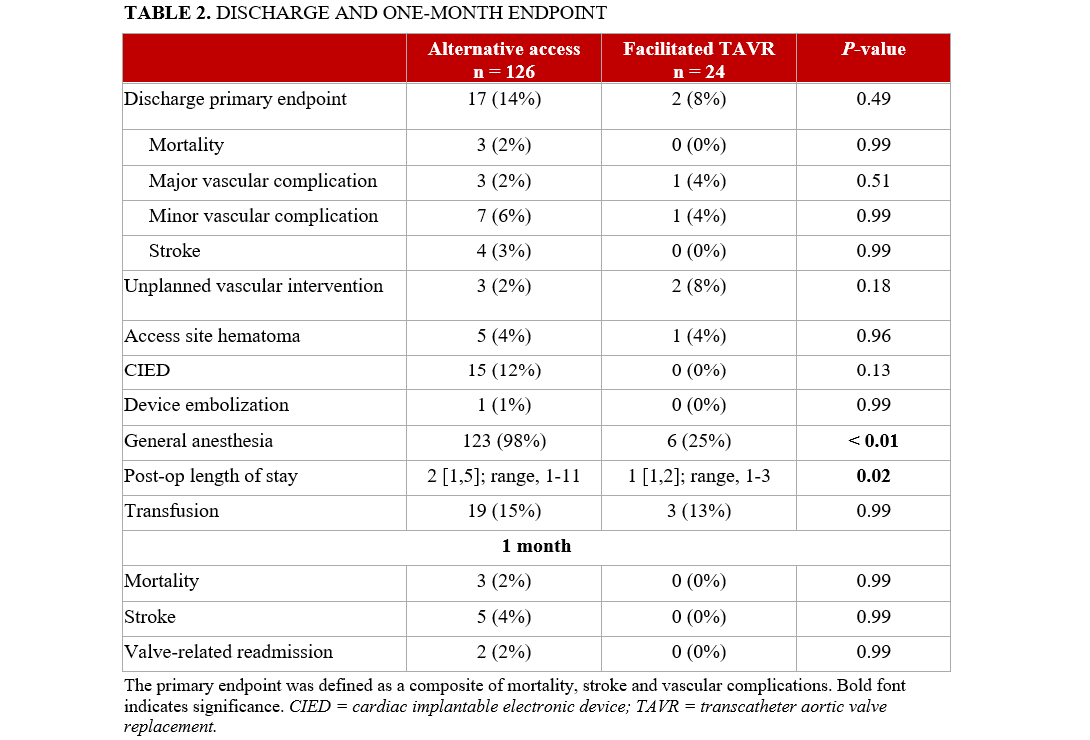

The composite primary endpoint of mortality, stroke, or vascular complications occurred more frequently in the alternative access group compared with the facilitated TF access group (14% vs 8%), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .49) (Table 2). General anesthesia was used significantly more often in the alternative access group (98% vs 25%; P < .01). The postoperative LOS was also longer in the alternative access group (2 days vs 1 day; P = .02).

A trend toward a higher rate of new cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) implantation was observed in the alternative access group (12% vs 0%; P = .13). Rates of unplanned vascular intervention were higher in the facilitated TF group (8% vs 2%), though this difference was not statistically significant. Mortality rates were comparable between the 2 groups at both discharge and at the 1-month follow-up, with no statistically significant differences observed.

Discussion

When TF access is not feasible, alternative approaches must be considered for TAVR. This study compared procedural and clinical outcomes between facilitated TF access TAVR and conventional alternative access TAVR. Although postprocedural complication rates were similar between groups, patients with severe PAD who underwent facilitated TF access TAVR experienced a shorter hospital stay and significantly less use of general anesthesia.

The HOSTILE score has recently emerged as a valuable tool to quantify the severity and extent of iliofemoral disease in patients with PAD. By incorporating parameters such as minimal luminal diameter, calcium burden, and vessel tortuosity, the HOSTILE score provides a standardized and objective assessment of anatomic complexity. In a multicenter study, Palmerini et al demonstrated significantly lower 30-day and 1-year major adverse events with facilitated TF access TAVR compared withh transthoracic access approaches.10 They defined a high HOSTILE score as greater than 8.5, which was independently associated with increased mortality.10 Despite a higher mean HOSTILE score (10.7) in our facilitated TF group compared with the threshold identified by Palmerini et al, outcomes in our cohort were comparable to those observed with alternative access strategies (Table 1). In our study, vascular access selection was determined at the discretion of the primary operator and may have been influenced by anatomic factors such as heavy anterior wall calcification of the common femoral artery, which can render the puncture site unsuitable despite otherwise favorable iliofemoral anatomy. Operator experience, collaboration with vascular or cardiothoracic surgery, and institutional practice patterns likely also contributed to the decision-making process; a detailed evaluation of these individual anatomic considerations is beyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, the absence of a statistically significant difference in HOSTILE scores between groups suggests that both cohorts demonstrated comparable degrees of anatomic complexity. Thus, for patients with severe iliofemoral PAD or high HOSTILE score, IVL is a safe and feasible option to modify iliofemoral calcifications.

Previous studies have highlighted the utility of facilitated access TAVR as an appropriate choice for patients with severe lower extremity PAD. When compared with transaxillary access specifically, Linder et al demonstrated decreased major adverse outcomes (all-cause death, stroke, bleeding) with facilitated access TAVR.14 Similarly, Nardi et al demonstrated the safety of facilitated TAVR with 100% successful TF aortic valve delivery with few complications.12 Consistent with these findings, our study also achieved 100% device delivery success.

Facilitated access has evolved since its first use for TAVR in patients with severe lower extremity PAD. Several complications were reported after its inception, all mainly related to severe atherosclerotic disease including vessel perforation/dissection, access-related bleeding, and stent/graft implantation.12 By fragmenting superficial and deep calcifications using acoustic shock waves, there is reduced risk for barotrauma-induced vessel perforation/dissection due to lower pressure balloon inflation required for this process.14

Two patients in the facilitated TF access group required unplanned vascular intervention—one because vessel perforation necessitating open repair with graft anastomosis, and another because of post-closure bleeding and hematoma following Perclose device (Abbott) deployment. This highlights the technical challenges of TAVR in patients with severe PAD, where Perclose sutures may anchor onto calcified plaque rather than the vessel wall, resulting in complications.15 Thus, despite there being no bleeding initially, suboptimal closure led to the postoperative bleed, requiring repair. In the alternative access group, 2 patients experienced iliofemoral injury necessitating open surgical repair at the site of the small-bore sheath used for pigtail catheter insertion. These cases highlight the inherent challenges of TF access, where even small-caliber sheaths may increase the risk of vascular complications in patients with diffuse PAD.

Retrograde embolization of atherosclerotic debris or iliac artery displacement during catheter advancement and catheter-induced embolization in the aortic arch or ascending aorta are also risks with severe PAD.10 Stroke risk is present and concerning in patients with severe PAD, but the use of cerebral embolic protection systems during facilitated access TAVR still requires further investigation.10 Our study did not show a statistically significant difference in stroke rates. However, other studies have reported a lower risk of stroke with facilitated access TAVR.10,12,14 Notably, 3 of the 4 strokes (75%) in the alternative access group occurred via a trans-subclavian approach.6

Permanent pacemaker (PPM) implantation is a concern after TAVR, and multiple factors, including anatomic and procedural characteristics and baseline electrophysiological variables, contribute to the overall risk.16 While there was no statistical significance, there was a slightly increased rate of PPM implantation in the alternative access TAVR group in our current study. Previous studies have reported variable rates of PPM implantation between TF vs alternative access. A propensity-matched study reported significantly increased PPM implantation with the TF approach compared to the transcarotid approach.17 Similarly, other retrospective studies have reported an increased trend of PPM implantation with TF access compared with alternative access, but this was not statistically significant.18,19 Conversely, a meta-analysis showed a 23% decreased risk in PPM implantation with the TF approach compared with the transaxillary approach.20 Although the exact reason for increased PPM implantation with alternative access is unknown, the prolonged procedural time leading to longer manipulation of the atrioventricular node can lead to higher chances of conduction disturbances and PPM implantation.20

Given the resource-intensive nature of TAVR, it is crucial to identify and optimize factors that contribute to reduced health-care resource utilization. Notably, the observed reduction in LOS by 1 day for facilitated access TAVR, in comparison to alternative access routes, represents a significant advantage. This decreased LOS can likely be attributed to the decreased use of general anesthesia in patients who underwent facilitated access TAVR. General anesthesia use in TAVR is known to be associated with increased LOS, anesthesia-related complications, 30-day mortality, and stroke.21,22 However, the choice of anesthetic is based upon the preoperative comorbidities and procedural approach.23 While TAVR can be performed with conscious sedation when using the TF approach, it is not preferred with a majority of alternative access approaches. This is because of the concern for lung injury, cardiac tamponade, and required limited movement.7 Thus, facilitated access TAVR is a useful choice when avoiding general anesthesia.

Limitations

Several limitations were present in the study. This is a retrospective study, so results may change over time. Our study had a small sample size, which may have contributed to the nonsignificant results in certain outcomes, including the primary outcome and PPM implantation. Our study did not utilize all alternative access approaches, including the transcaval approach. Our study also had several strengths worth mentioning. Our study was performed across 4 institutions with multiple operators, increasing our findings’ generalizability. Furthermore, we compared a composite of alternative access routes with the facilitated access route.

Conclusions

Facilitated TF access for TAVR may be associated with favorable procedural and clinical outcomes when compared with other alternative access approaches. In our study, this strategy was linked to a shorter LOS and markedly lower use of general anesthesia, which likely contributed to overall procedural efficiency and reduced resource utilization. Although the primary endpoint did not reach statistical significance, likely because of the study being underpowered, the numerical trend towards better outcomes, such as decreased stroke rates, in the facilitated TAVR group indicates a potential advantage. Large-scale prospective studies are required to determine the appropriate access strategy for TAVR in patients with concomitant severe aortic stenosis and PAD with challenging femoral anatomy.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Ahmad Mustafa, MD; Denny Wang, BS; Cole Dutton, BS; Arber Kodra, MD; Muhammad Abubakar Shakir, MD; Ythan Goldberg, MD; Mei Chau, MD; Shankar Thampi, MD; Priti Mehla, MD; Chapman Wei, MD; Shangyi Liu, MS; Michael Cinelli, MD; Bruce Rutkin, MD; Elana Koss, MD; Gregory Maniatis, MD; Alexander Iribarne, MD; Apurva Patel, MD; Sean Wilson, MD; Wally Omar, MD; Robert Kalimi, MD; Alan Hartman, MD; Jacob Scheinerman, MD; Chad Kliger, MD, MS

From the Cardiovascular Institute, Northwell, New Hyde Park, New York.

The abstract was previously presented at TCT 2024 and published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Mustafa A, Wang D, Dutton C, et al. TCT-906 facilitated transfemoral versus alternative access transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients with peripheral vascular disease: intra-procedural and 30-Day Outcomes. JACC. 2024;84(18_Supplement). doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2024.09.1092

Disclosures: Dr Patel serves as a consultant for Medtronic. The remaining authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Data availability: The data used in the study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Address for correspondence: Chad Kliger, MD, Department of Cardiovascular & Thoracic Surgery, Lenox Hill Hospital/Northwell Health, 130 East 77th Street, 4th floor, New York, NY 10075, USA. Email: ckliger@northwell.edu

References

1. Banks A, Gaca J, Kiefer T. Review of alternative access in transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2020;10(1):72-82. doi:10.21037/cdt.2019.10.01

2. Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, et al; Evolut Low Risk Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(18):1706-1715. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1816885

3. Adams DH, Popma JJ, Reardon MJ, et al; U.S. CoreValve Clinical Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding prosthesis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(19):1790-1798. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1400590

4. Thomas M, Schymik G, Walther T, et al. One-year outcomes of cohort 1 in the Edwards SAPIEN Aortic Bioprosthesis European Outcome (SOURCE) registry: the European registry of transcatheter aortic valve implantation using the Edwards SAPIEN valve. Circulation. 2011;124(4):425-433. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.110.001545

5. Kaneko T, Hirji SA, Yazdchi F, et al. Association between peripheral versus central access for alternative access transcatheter aortic valve replacement and mortality and stroke: a report from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15(9):e011756. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.011756

6. Sherwood M, Allen KB, Dahle TG, et al. SCAI expert consensus statement on alternative access for transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2025;4(3Part A):102514. doi:10.1016/j.jscai.2024.102514

7. Fanaroff AC, Manandhar P, Holmes DR, et al. Peripheral artery disease and transcatheter aortic valve replacement outcomes: a report from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Therapy registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(10):e005456. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.117.005456

8. Généreux P, Webb JG, Svensson LG, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Vascular complications after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: insights from the PARTNER (Placement of AoRTic TraNscathetER Valve) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(12):1043-1052. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.003

9. Bechara CF, Annambhotla S, Lin PH. Access site management with vascular closure devices for percutaneous transarterial procedures. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52(6):1682-1696. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2010.04.079

10. Palmerini T, Saia F, Kim WK, et al. Vascular access in patients with peripheral arterial disease undergoing TAVR: the Hostile registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16(4):396-411. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2022.12.009

11. Di Mario C, Chiriatti N, Stolcova M, Meucci F, Squillantini G. Lithotripsy-assisted transfemoral aortic valve implantation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(28):2655. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy021

12. Nardi G, De Backer O, Saia F, et al. Peripheral intravascular lithotripsy for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a multicentre observational study. EuroIntervention. 2022;17(17):e1397-e1406. doi:10.4244/eij-d-21-00581

13. Généreux P, Piazza N, Alu MC, et al; VARC-3 WRITING COMMITTEE. Valve Academic Research Consortium 3: updated endpoint definitions for aortic valve clinical research. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(21):2717-2746. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.02.038

14. Linder M, Grundmann D, Kellner C, et al. Intravascular lithotripsy-assisted transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe iliofemoral calcifications: expanding transfemoral indications. J Clin Med. 2024;13(5):1480. doi:10.3390/jcm13051480

15. Durmuş G, Belen E, Bayyiğit A, Can MM. Comparison of complication and success rates of ProGlide closure device in patients undergoing TAVI and endovascular aneurysm repair. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:2687862. doi:10.1155/2018/2687862

16. Batta A, Hatwal J. Risk of permanent pacemaker implantation following transcatheter aortic valve replacement: which factors are most relevant? World J Cardiol. 2024;16(2):49-53. doi:10.4330/wjc.v16.i2.49

17. Olivier ME, Di Cesare A, Poncet A, et al. Transfemoral versus transcarotid access for transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JTCVS Tech. 2022;15:46-53. doi:10.1016/j.xjtc.2022.05.019

18. Arai T, Romano M, Lefèvre T, et al. Direct comparison of feasibility and safety of transfemoral versus transaortic versus transapical transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9(22):2320-2325. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2016.08.009

19. Gleason TG, Schindler JT, Hagberg RC, et al. Subclavian/axillary access for self-expanding transcatheter aortic valve replacement renders equivalent outcomes as transfemoral. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105(2):477-483. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.07.017

20. Abusnina W, Machanahalli Balakrishna A, Ismayl M, et al. Comparison of transfemoral versus transsubclavian/transaxillary access for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2022;43:101156. doi:10.1016/j.ijcha.2022.101156

21. Arbel Y, Zivkovic N, Mehta D, et al. Factors associated with length of stay following trans-catheter aortic valve replacement - a multicenter study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):137. doi:10.1186/s12872-017-0573-7

22. Fadah K, Khalafi S, Corey M, et al. Optimizing anesthetic selection in transcatheter aortic valve replacement: striking a delicate balance between efficacy and minimal intervention. Cardiol Res Pract. 2024;2024:4217162. doi:10.1155/2024/4217162

23. Afshar AH, Pourafkari L, Nader ND. Periprocedural considerations of transcatheter aortic valve implantation for anesthesiologists. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2016;8(2):49-55. doi:10.15171/jcvtr.2016.10