Self-Expanding Aortic Endografts for Endovascular Repair of Native and Recurrent Coarctation of the Aorta

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2026. doi:10.25270/jic/25.00394. Epub January 23, 2026.

Abstract

Objectives. Endovascular repair of coarctation of the aorta (CoA) can be challenging in the presence of arch angulation, post-stenotic dilation, or prior surgical repair, which may limit the performance of balloon-expandable covered stents. To address these anatomic constraints, the authors evaluated the use of a self-expanding thoracic aortic endoprosthesis for CoA repair.

Methods. The authors performed a multicenter retrospective review of patients who underwent endovascular repair of native or recurrent CoA using the GORE TAG Thoracic Branch Endoprosthesis Extender or GORE TAG Conformable Thoracic Stent Graft (W.L. Gore & Associates) between January 1, 2023, and December 31, 2025.

Results. Thirteen patients (median age 32 years; range, 21-49 years; 77% male) underwent endovascular treatment. All patients exhibited significant baseline peak-to-peak gradients (median = 23 mm Hg; IQR: 10, 27). Hemodynamic resolution was achieved in all cases (median = 0 mm Hg; IQR: 0, 2; P < .001). Median waist diameter increased from 11 mm (IQR: 9, 12) to 20 mm (IQR: 18, 22) (P < .001). Aortic isthmus ratio increased from 0.46 (IQR: 0.39, 0.54) to 0.87 (IQR: 0.77, 0.92) (P < .001). No intraprocedural complications were observed.

Conclusions. Self-expanding thoracic endografts demonstrated excellent conformability, effective gradient elimination, and early procedural success in the treatment of CoA. Continued follow-up, including protocolized imaging, will be essential to assess mid- and long-term durability and to define the role of this approach in patients with complex aortic anatomy.

Introduction

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) accounts for approximately 6% to 8% of congenital heart disease and may present in isolation or in association with additional structural or genetic abnormalities.1,2 Clinical presentation varies by age and disease severity, ranging from systemic hypertension and upper-lower extremity blood pressure gradients in adolescents and adults to ductal-dependent systemic perfusion and cardiovascular collapse in neonates. While surgical repair remains the standard of care in early infancy, advances in transcatheter therapy have substantially expanded the role of endovascular therapy for both primary intervention and reintervention.3

Over the past 3 decades, stent-based therapy has evolved from bare-metal balloon-expandable stents to covered platforms capable of addressing more complex anatomy, including tortuous arches and postsurgical aneurysms. Large multicenter studies have demonstrated favorable outcomes, with the COAST I (Coarctation of the Aorta Stent Trial) showing immediate and sustained relief of transaortic gradients and improved systemic blood pressure, and the COAST II trial demonstrating comparable efficacy with added protection against aortic wall injury using covered Cheatham Platinum stents (NuMED).4-7 Nonetheless, ongoing rates of stent fracture and reintervention have been reported, underscoring persistent limitations of existing stent platforms.8

Technical challenges therefore remain in the endovascular management of CoA, including stress imparted to the aortic wall during balloon inflation, difficulty achieving uniform apposition in highly angulated arches, and the fixed geometry of rigid stent frames. To address these anatomical and mechanical constraints, we report our experience using a self-expanding thoracic aortic endoprosthesis for endovascular repair of CoA, highlighting its feasibility, enhanced arch conformability, and favorable early hemodynamic outcomes.

Methods

This study was determined to be exempt from institutional review board oversight. Informed consent was obtained from the patients for the intervention described and for the publication of their deidentified data. We conducted a 2-center retrospective analysis of patients with CoA who underwent endovascular repair between January 1, 2023, and December 31, 2025 at the Mayo Clinic and the Saint Francis Heart and Vascular Institute using the GORE TAG Thoracic Branch Endoprosthesis Extender or the GORE TAG Conformable Thoracic Stent Graft (W.L. Gore & Associates).9 For simplicity, these devices are hereafter referred to as the aortic extender and CTAG, respectively. Only tubular endograft configurations were included; cases involving branched systems were excluded. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for the procedures performed and for publication of their cases, including all associated images.

Preoperative transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and computed tomography angiography (CTA) were performed in all patients to define aortic anatomy, assess hemodynamic severity, and identify associated congenital or arch-related abnormalities. Initial selection for endovascular graft utilization was at the discretion of the treating operator in patients with isolated CoA without associated lesions requiring concurrent surgical intervention. All cases underwent multidisciplinary review to confirm the optimal management strategy (open surgical vs endovascular) based on anatomic and clinical considerations. Following the introduction of self-expanding endovascular grafts into clinical practice, our physicians transitioned to exclusive use of this platform for endovascular repair of CoA; during the study period, no patients who met the criteria for endograft placement were treated with a balloon-expandable covered stent.

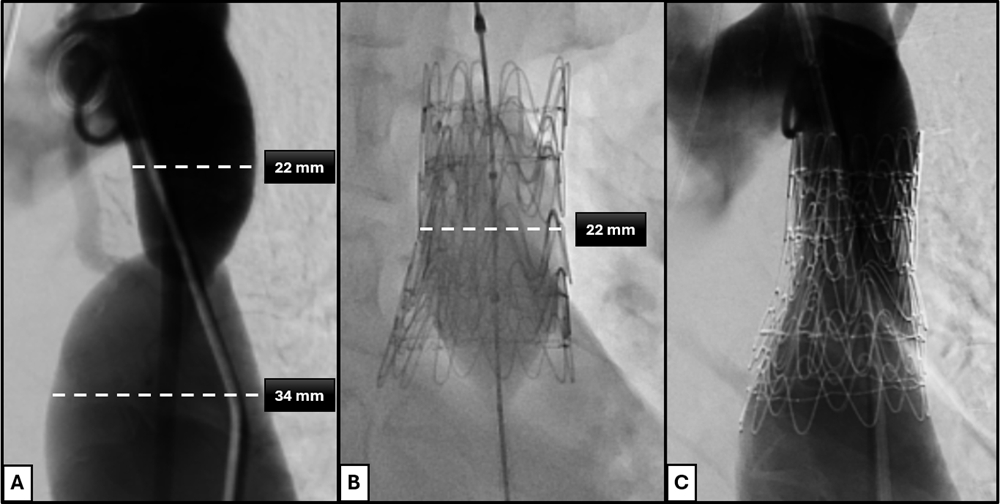

Graft implantation was followed by high-pressure noncompliant balloon dilation. Balloon diameter was matched to the native aortic dimension immediately proximal to the target segment, avoiding overexpansion. Controlled effacement of the external vascular waist served as confirmation of intimal expansion and procedural success; no further modification (ie, reinforcement with bare metal stent implantation) was performed even when recoil persisted.

Demographic characteristics, imaging findings, procedural variables, and short-term outcomes were evaluated. Categorical variables were reported as frequency (%), and continuous variables as median (25th, 75th percentiles). Paired comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test because of the non-normal distribution of the data.

Results

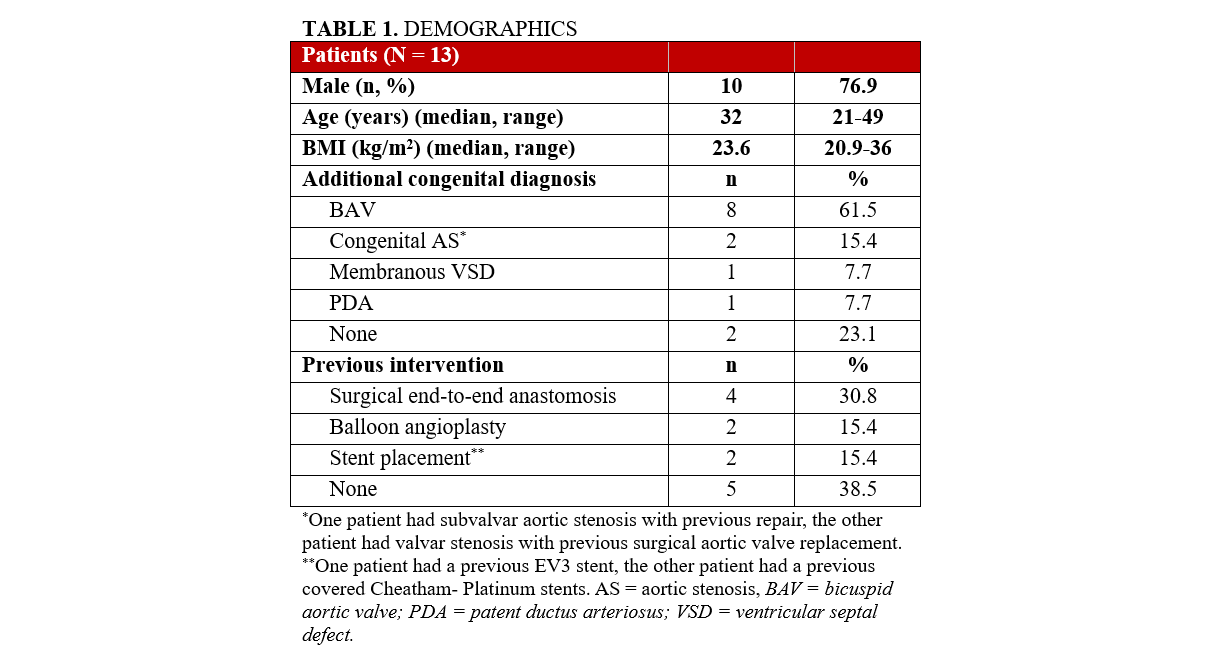

Thirteen patients (median age 32 years; range, 21-49 years; 77% male) have undergone the procedure to date (December 2025), the majority of whom had associated congenital cardiac diagnosis. Patient demographics and congenital cardiac diagnoses are summarized in Table 1. All patients were symptomatic, presenting with hypertension and/or exertional claudication. Most had unrepaired native coarctation (n = 5, 39%), while the remainder had prior procedures: balloon angioplasty (n = 2, 15%), stent placement (n = 2, 15%), or surgical end-to-end repair (n = 4, 31%). One patient (8%) underwent concomitant transcatheter aortic valve-in-valve replacement for bioprosthetic stenosis.

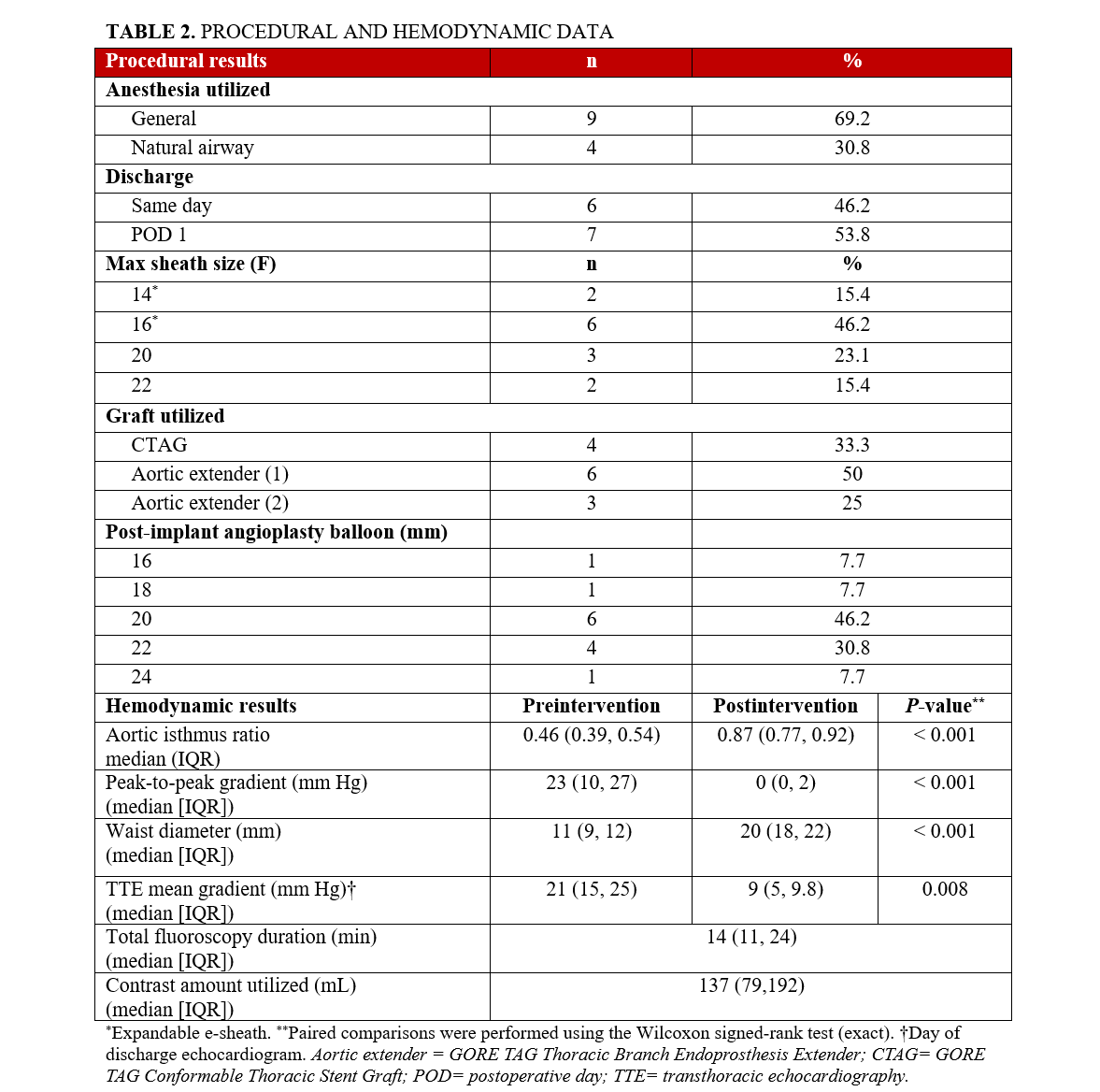

Procedural and hemodynamic data are outlined in Table 2. In brief, large-bore femoral arterial access was utilized for initial angiography and device delivery, with secondary radial access used for hemodynamic monitoring and check angiography. The maximum sheath size ranged from 14F to 22F (14F [n = 2, 15%], 16F [n = 6, 46%], 20F [n = 3, 23%], and 22F [n = 2, 15%]), reflecting an evolution in practice with early cases using larger sheaths and later cases demonstrating successful deployment through 14F to 16F Edwards expandable eSheaths (Edwards Lifesciences). All patients demonstrated significant peak-to-peak ascending-to-descending (Asc-Dsc) aortic gradients at baseline (median = 23 mm Hg; IQR: 10, 27). Most required a single aortic extender (n = 6, 46%), while 3 patients (23%) required 2 aortic extenders. CTAGs were used in 4 early cases (31%). High-pressure noncompliant balloon dilation was performed after endograft deployment, and completion angiography confirmed the absence of uncontained aortic disruption in all procedures.

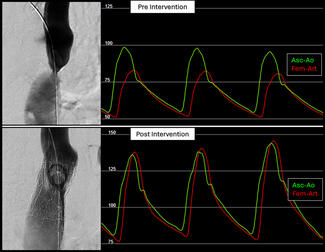

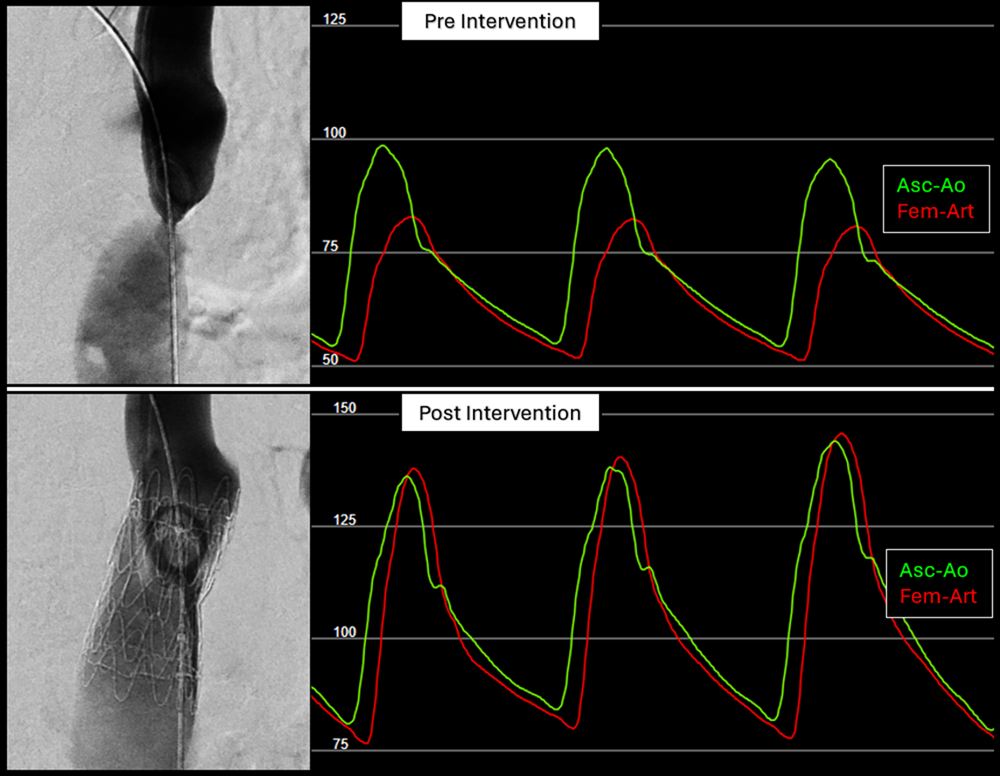

Postintervention invasive measurements revealed no residual Asc-Dsc gradient (median = 0 mm Hg; IQR: 0, 2; P < .001). Several patients demonstrated physiologic pressure reversal (femoral arterial systolic pressure > ascending systolic pressure; Figure 1), consistent with normalization of arch physiology (Figure 1). Negative gradients were not recorded and were documented as 0. The median waist diameter increased from 11 (IQR: 9, 12) to 20 mm (IQR: 18, 22) (P < .001). Aortic isthmus ratio increased from 0.46 (IQR: 0.39, 0.54) to 0.87 (IQR: 0.77, 0.92) (P < .001). No intraprocedural complications occurred.

Patients were discharged on either the same day (n = 6, 46%) or the following day (n = 7, 54%); all but 1 patient (8%) had a surface echocardiogram prior to discharge. TTE-derived mean systolic gradients decreased from 21 mm Hg (IQR: 15, 25) preintervention to 9 mm Hg (IQR: 5, 9.8) postintervention (P = .008). Among the 4 patients with at least a 6-month follow-up, 2 patients (15%) have had CT angiograms. Imaging confirmed expected graft expansion and sustained hemodynamic improvement, with a Doppler-derived systolic mean descending aortic gradient of 3 mm Hg (IQR: 3, 4). To date, no patient has required reintervention (follow-up range, 6-21 months).

Discussion

This report represents the first systematic application of the GORE TAG Thoracic Branch Endoprosthesis Extender and GORE TAG Conformable Thoracic Stent Graft platforms specifically for endovascular repair of aortic coarctation, beyond their previously described use in aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm pathology.10 In this cohort, endovascular repair resulted in consistent and complete resolution of coarctation gradients, with normalization of hemodynamics in all patients (Table 2). Notably, the implanted grafts demonstrated dynamic conformational changes during systole following procedural completion (Video), behavior more consistent with the expansile properties of native aortic tissue than with a rigid, closed-cell stent frame. In prior clinical trials of stent-based coarctation therapy, procedural success was defined by effective gradient reduction (peak-to-peak < 20 mm Hg or upper-lower systolic blood pressure difference < 20 mm Hg) and restoration of luminal diameter to match the descending aorta (improvement of aortic isthmus ratio).4,8,11 Our early results met these established benchmarks; however, it will be of particular interest to determine whether the dynamic behavior of a self-expanding endograft promotes a more physiologic flow profile and whether this translates into improved central blood pressure control and reverse left ventricular remodeling over time.

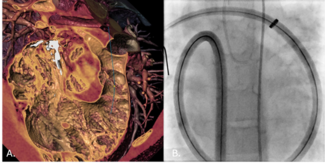

From an anatomic perspective, the segmented nitinol architecture and self-expanding design enables reliable conformability to the coarctation segment, accommodating marked differences between inflow and outflow diameters while achieving complete luminal coverage prior to balloon dilation (Figure 2). Structural integrity was maintained without infolding, even when the graft was substantially under-deployed (waist < 30% of nominal graft diameter, eg, a 37-mm implant across a 9-mm coarctation). Radiopaque graft markers facilitate accurate positioning and overlap when extensions were required, and the availability of additional extenders or CTAG modules allows optimization of proximal or distal sealing, including extension into the aortic arch distal to the left carotid artery when anatomically or emergently indicated. These features, which we and others have previously described in related applications, support the adaptability of this platform for complex coarctation anatomy.12,13

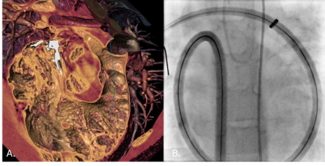

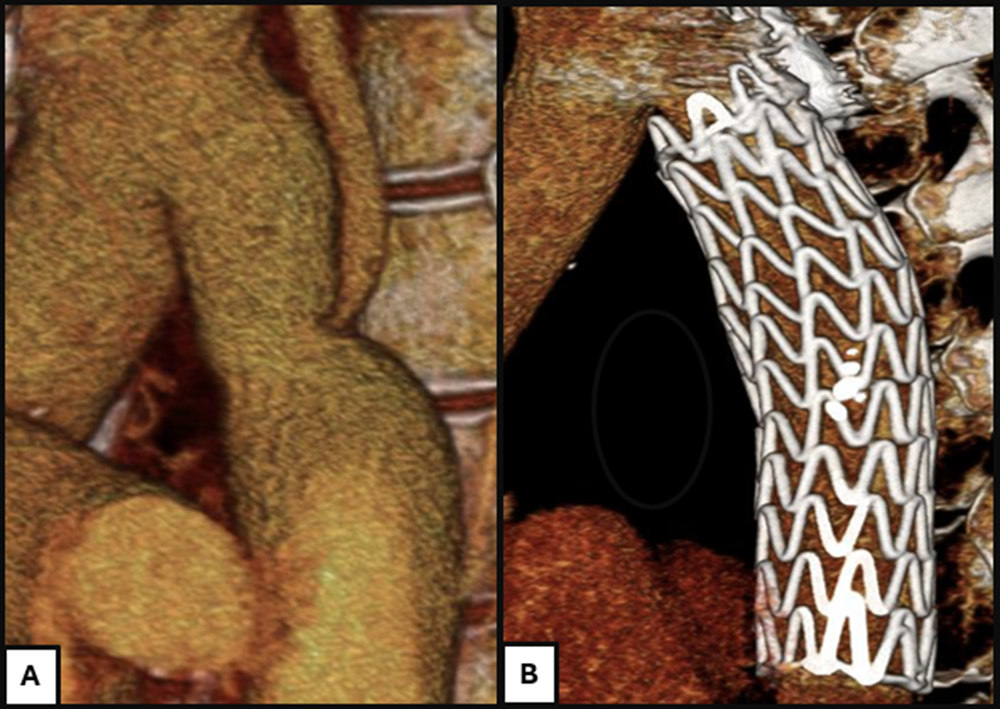

Aortic wall injury associated with balloon angioplasty, bare-metal stents, and covered stents has been well described.14,15 Establishing a continuous endovascular covering prior to angioplasty represents a fundamental shift in lesion management, as subsequent high-pressure dilation can be intentionally confined within the grafted segment. In contrast, dissection occurring during balloon-expandable covered-stent deployment may necessitate additional covering implantation and repeated balloon dilations, potentially propagating dissection proximally or distally and complicating management. With the endograft approach, effacement of the coarctation waist served as the procedural endpoint, and mild residual recoil was accepted. Although concern exists regarding recurrent waist formation or restenosis related to abnormal tissue at the coarctation site, we hypothesize that effective angioplasty results in controlled dissection of the aortic tissue external to the graft, leading to progressive expansion over time rather than recoil (Figure 3). Prospective multicenter studies and protocolized postprocedural imaging will be required to validate this hypothesis.

Despite labeled requirements for 20F to 26F access,9 devices were successfully delivered through a 14F to 16F expandable e-sheath. This reduction in access profile is clinically relevant because of the well-established association between large-bore sheaths and access morbidity, particularly in adolescents and young adults.16-17 Ultrasound-guided femoral access and closure devices were routinely employed, and no access site complications occurred. Because the expandable sheath is short, deployment proceeded without a formal unsheathing maneuver; in this setting, traction from the retention sleeve may transmit force to the graft. To prevent displacement, the previously described technique of cutting the suture that secures the sleeve to the delivery handle was routinely employed, except in cases requiring deployment near supra-aortic branch origins.18

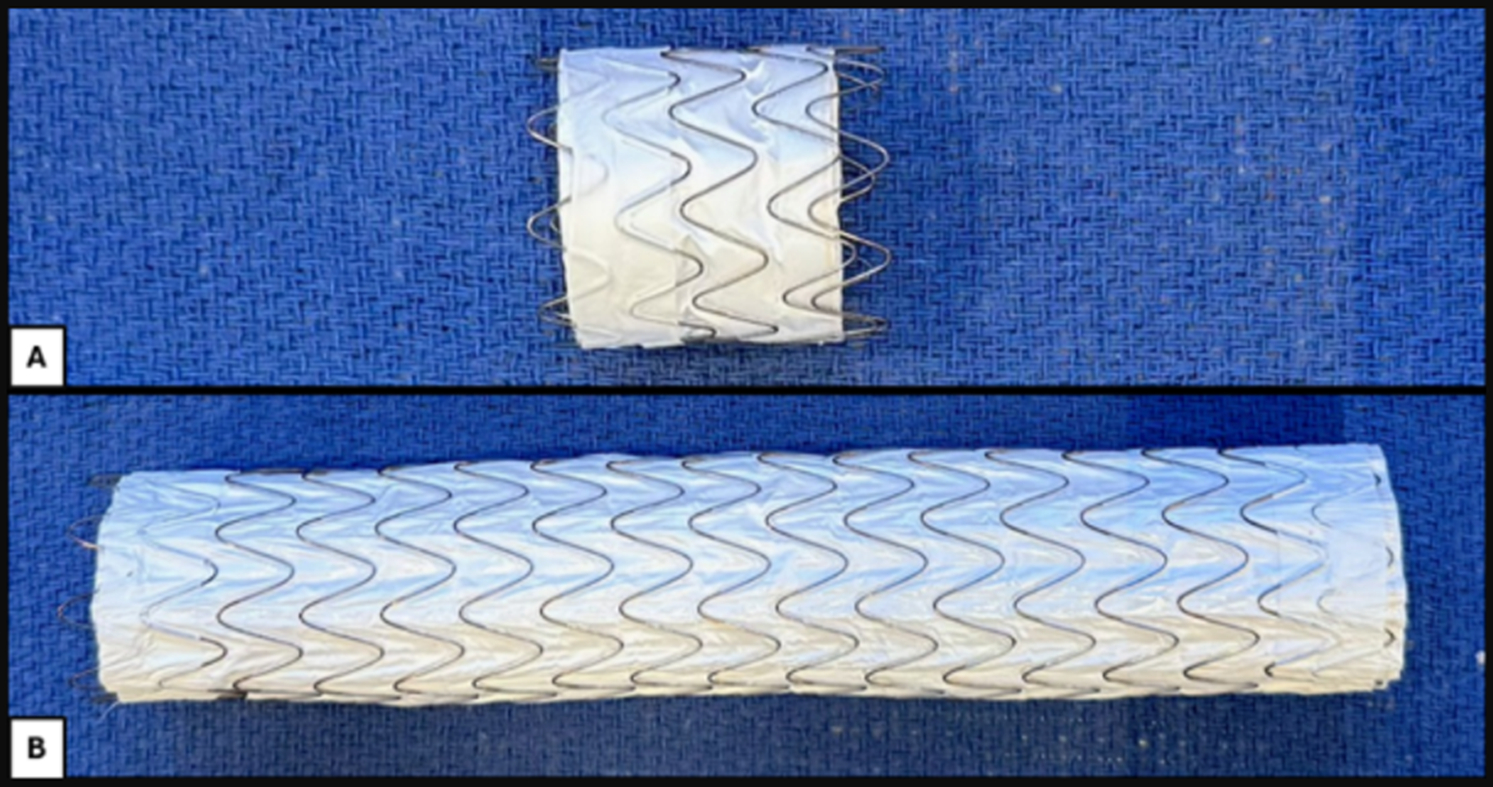

As our practice transitioned to endovascular graft-based repair, questions emerged regarding the need for cerebrospinal fluid drainage to mitigate the risk of spinal cord ischemia, a complication associated with substantial morbidity and mortality and one that may be easily misdiagnosed.19 This consideration is rarely discussed in the context of stent implantation—including covered stents—for coarctation repair. In contrast, spinal cord ischemia is a recognized complication of other surgical and endovascular interventions of the abdominal aorta, with reported rates of up to 15% depending on the extent of aortic coverage and baseline patient risk.20-21 Endovascular repair of coarctation, however, typically involves limited coverage confined to the aortic isthmus, preserving radiculomedullary inflow, including the artery of Adamkiewicz. This principle is reflected in use of the thoracic branch extender, which provides 3.6 to 4.6 cm of coverage depending on diameter, compared with the longer 10-cm CTAG configuration (Figure 4).9 Limiting coverage to the minimum necessary helps preserve spinal cord perfusion. Accordingly, routine prophylactic cerebrospinal fluid drainage was not performed, with intervention reserved for the rare occurrence of postoperative neurologic deficit—which was not observed in this cohort.

In summary, this report outlines a strategy intended to improve the safety and predictability of endovascular management of aortic coarctation. These data demonstrate acute procedural success and favorable early safety and provide the foundation for larger, multicenter studies with mid- and long-term follow-up, including comparative evaluation against surgical repair and prior balloon-expandable stent platforms.

Limitations

This study is limited by the current availability of only short-term follow-up, although protocolized surveillance with 1-year CT angiography has now been implemented. Selection bias may have influenced device use and outcomes. Broader adoption is further limited by variable access to the expandable e-sheath and difficulty obtaining these endografts in free-standing children’s hospitals and smaller programs; however, centers with established access benefit from off-the-shelf availability, allowing rapid integration into clinical practice without the need for custom device procurement. Multicenter participation with standardized imaging surveillance and randomized comparison of stent-based and graft-based platforms would be ideal to validate these early results, assess long-term durability, and determine whether a superior platform exists.

Conclusions

Self-expanding endografts achieved effective CoA relief with procedural success and no complications. These observations support selective adoption of this modality for complex or recurrent CoA, with continued surveillance needed to establish sustained long-term outcomes.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Kaitlyn Krebushevski, DO1,2; Allison K. Cabalka, MD1,2; Nathaniel W. Taggart, MD1,2; Pradyumna Agasthi, MD3; Alexander C. Egbe, MBBS2; William R. Miranda, MD2; Peter M. Pollak, MD4; Abigail M. Sutter, PA-C1,2; Frank Cetta, MD1,2; Jason H. Anderson, MD1,2

From the 1Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, Division of Pediatric Cardiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota; 2Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Division of Structural Heart Diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota; 3Department of Cardiology, Saint Francis Heart and Vascular Institute, Tulsa, Oklahoma; 4Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida.

Disclosures: Dr Cabalka is a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Inc., and B. Braun Medical, Inc. Dr Pollak is a consultant for W.L. Gore & Associates. Dr Anderson serves on a cardiac advisory board for W.L. Gore & Associates and is a consultant for Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences. The remaining authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Address for correspondence: Kaitlyn Krebushevski, DO, 1216 2nd St SW, Rochester, MN 55902, USA. Email: Krebushevski.kaitlyn@mayo.edu; X: @Kaitlynkreb, @Dr_JHAnderson

References

- Feltes TF, Bacha E, Beekman RH III, et al; American Heart Association Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; American Heart Association. Indications for cardiac catheterization and intervention in pediatric cardiac disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(22):2607-2652. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31821b1f10

- Writing Committee Members, Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(24):e223-e393. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.08.004

- Stephens EH, Feins EN, Karamlou T, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons clinical practice guidelines on the management of neonates and infants with coarctation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2024;118(3):527-544. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2024.04.012

- Butera G, Manica JL, Marini D, et al. From bare to covered: 15-year single center experience and follow-up in trans-catheter stent implantation for aortic coarctation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;83(6):953-963. doi:10.1002/ccd.25404

- Schleiger A, Al Darwish N, Meyer M, Kramer P, Berger F, Nordmeyer J. Long-term follow-up after endovascular treatment of aortic coarctation with bare and covered Cheatham platinum stents. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;102(4):672-682. doi:10.1002/ccd.30793

- Meadows J, Minahan M, McElhinney DB, McEnaney K, Ringel R; COAST Investigators. Intermediate outcomes in the prospective, multicenter coarctation of the aorta stent trial (COAST). Circulation. 2015;131(19):1656-1664. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013937

- Taggart NW, Minahan M, Cabalka AK, et al; COAST II Investigators. Immediate outcomes of covered stent placement for treatment or prevention of aortic wall injury associated with coarctation of the aorta (COAST II). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9(5):484-493. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2015.11.038

- Holzer RJ, Gauvreau K, McEnaney K, Watanabe H, Ringel R. Long-term outcomes of the coarctation of the aorta stent trials. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(6):e010308. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.120.010308

- W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc. GORE® TAG® Thoracic Branch Endoprosthesis Instructions for Use. US Food and Drug Administration. P210032C. Accessed December 17, 2025. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf21/P210032C.pdf

- Erben Y, Oderich GS, Verhagen HJM, et al. Multicenter experience with endovascular treatment of aortic coarctation in adults. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69(3):671-679.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2018.06.209

- Yang L, Chua X, Rajgor DD, Tai BC, Quek SC. A systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes of transcatheter stent implantation for the primary treatment of native coarctation. Int J Cardiol. 2016;223:1025-1034. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.295

- Krebushevski K, Cabalka AK, Pollak PM, Yu L, Anderson JH. Self-expanding aortic endoprosthesis for conduit preparation prior to transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;106(4):2244-2251. doi:10.1002/ccd.70039

- Agasthi P, Mendes BC, Cabalka AK, et al. Thoracic branching endoprosthesis for management of coarctation of the aorta with subclavian artery involvement. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2024;3(4):101335. doi:10.1016/j.jscai.2024.101335

- Castaldi B, Ciarmoli E, Di Candia A, et al. Safety and efficacy of aortic coarctation stenting in children and adolescents. Int J Cardiol Congenit Heart Dis. 2022;8:100389. doi:10.1016/j.ijcchd.2022.100389

- Tretter JT, Jones TK, McElhinney DB. Aortic wall injury related to endovascular therapy for aortic coarctation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(9):e002840. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.002840

- Golden AB, Hellenbrand WE. Coarctation of the aorta: stenting in children and adults. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;69(2):289-299. doi:10.1002/ccd.21009

- Forbes TJ, Garekar S, Amin Z, et al; Congenital Cardiovascular Interventional Study Consortium (CCISC). Procedural results and acute complications in stenting native and recurrent coarctation of the aorta in patients over 4 years of age: a multi-institutional study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;70(2):276-285. doi:10.1002/ccd.21164

- Anderson JH, Krebushevski K, Cabalka AK, Sutter AM, Taggart NW, Agasthi P. Modified deployment of a self-expanding aortic endoprosthesis for congenital aortic and conduit repair applications. J Invasive Cardiol. 2025. doi: 10.25270/jic/25.00368

- Zalewski NL, Rabinstein AA, Krecke KN, et al. Characteristics of spontaneous spinal cord infarction and proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(1):56-63. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2734

- Scali ST, Giles KA, Wang GJ, et al. National incidence, mortality outcomes, and predictors of spinal cord ischemia after thoracic endovascular aortic repair. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72(1):92-104. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2019.09.049

- Zalewski NL, Rabinstein AA, Krecke KN, et al. Spinal cord infarction: clinical and imaging insights from the periprocedural setting. J Neurol Sci. 2018;388:162-167. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2018.03.029