Outcomes of Impella 5.5-Supported Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients With Cardiogenic Shock

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2025. doi:10.25270/jic/25.00250. Epub December 8, 2025.

Abstract

Objectives. The use of a microaxial flow pump (mAFP) to support high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (HRPCI) in patients with cardiogenic shock (CS) is well established. A high-flow, surgically implanted mAFP (Impella 5.5, Abiomed/Johnson & Johnson MedTech) is increasingly used in patients with CS, yet little is known about the outcomes in HRPCI. The authors aimed to describe the outcomes, patient and procedural characteristics of Impella 5.5-supported HRPCI in a high-volume center.

Methods. The authors identified all adult patients who underwent Impella 5.5-supported percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) at Providence St. Vincent Medical Center from January 1, 2021, to December 31, 2024. Patient demographics and clinical data were abstracted from the medical record. Categorical data were reported as frequency and percentage. Continuous variables represented by intervals were summarized using mean and SD or median and IQR.

Results. Of the 34 patients identified, 31 were male, and the mean age was 62.9 (± 9.7) years. All patients had a maximal CS stage of C-E. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 24.3%. Unprotected left main was treated in 50% of the study cohort, and 94% of the patients required multivessel PCI. The mean SYNTAX score was 35.9 (± 10.8) and the residual SYNTAX score was 7.4 (± 5.9). Major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events occurred in 41% of the patients. The 90-day all-cause mortality was 38%.

Conclusions. Impella 5.5 is feasible to support HRPCI in patients with severe multivessel coronary artery disease, severe heart failure, and CS with acceptable short- and intermediate-term patient outcomes.

Introduction

The use of a microaxial flow pump (mAFP) (Impella 2.5/CP, Abiomed/Johnson & Johnson MedTech) to support high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (HRPCI) in patients with complex coronary artery disease (CAD), left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, and cardiogenic shock (CS) has been well studied.1-3 There are limitations with the use of femoral access for mAFP support, including severe peripheral arterial disease or tortuosity that precludes the insertion of a femoral artery mAFP.4,5 Long-term support with a femoral artery mAFP is also associated with risks of bleeding, limb ischemia, arterial thrombus formation, hemolysis, and acute renal failure.4,6

Patients with CS requiring urgent revascularization represent a population with high morbidity and mortality.7 Routine hemodynamic support with intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) or venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) for patients with acute myocardial infarction cardiogenic shock (AMICS) has not shown significant benefit.8,9 Recently, the DanGeR shock trial showed lower mortality in patients with AMICS treated with a mAFP despite higher rates of bleeding, limb ischemia, and acute kidney injury.6 However, there is little data on patients requiring urgent complex coronary revascularization with persistent or worsening shock despite vasoactive/inotropic support and treatment with a mechanical circulatory support (MCS) device.

A surgically implanted mAFP (Impella 5.5) provides greater left ventricular hemodynamic support than a percutaneous mAFP and is increasingly used to support patients with CS.10,11 The Impella 5.5 is inserted through a vascular conduit anastomosed to the aorta or axillary artery, allowing for a longer duration of support, patient mobilization, and reduced risks of limb ischemia and hemolysis.11,12

The use of Impella 5.5 to support HRPCI in patients with cardiogenic shock remains poorly described. In this report, we present a case series of patients with CS undergoing Impella 5.5-supported HRPCI.

Methods

We queried the electronic medical record to identify adult patients who underwent Impella 5.5-supported HRPCI at our center from January 1, 2021 to December 31, 2024. Patients who required Impella 5.5 placement as bailout post-PCI were excluded. The decision to implant the Impella 5.5 as a primary device or to upgrade to the Impella 5.5 was made by the multidisciplinary shock team. Baseline characteristics, comorbidities, laboratory data, vital signs, and echocardiographic data were extracted. The Charlson Comorbidity Index and the baseline and maximal Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions-Cardiogenic Shock Working Group (SCAI-CSWG) stages were computed for all patients.13-15 CS was defined as a systolic blood pressure of less than or equal to 90 mm Hg with evidence of organ hypoperfusion or management with inotropes or MCS. Guideline-directed medical therapy scores were calculated for all patients who were discharged using the Heart Failure Collaboratory scoring (HFCS) system.16

Angiographic and procedural characteristics were recorded, and the Synergy between PCI with TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery (SYNTAX) score, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) SYNTAX score, and residual SYNTAX score were calculated.17,18 If a patient had staged PCI during their hospitalization while being supported with Impella 5.5, the residual SYNTAX score was calculated after the final PCI. Coronary artery lesions were classified per the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force (ACC/AHA) classification if PCI was performed.19 The Multicenter Chronic Total Occlusion Registry of Japan (J-CTO) score was calculated for every patient with a chronic total occlusion (CTO).20

We collected major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) at 30 and 90 days. MACCE was defined as the composite of all-cause mortality, stroke/transient ischemic attack, myocardial infarction, and target vessel revascularization. Adverse events were defined according to published criteria.21 Sepsis was defined as organ dysfunction and tissue hypoperfusion with associated positive blood cultures.6

Categorical data were reported as frequency and percentage. Continuous variables represented by intervals were summarized using the mean of each interval. For numeric variables that had upper bounds, the highest number was used as the representative value. Numeric variables were summarized according to their distribution: those with a normal distribution were presented using the mean and SD, while skewed variables were described using the median and IQR. Analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide 8.3.

The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at Providence St. Vincent Medical Center (PSVMC). Informed consent was waived by the IRB at PSVMC.

Results

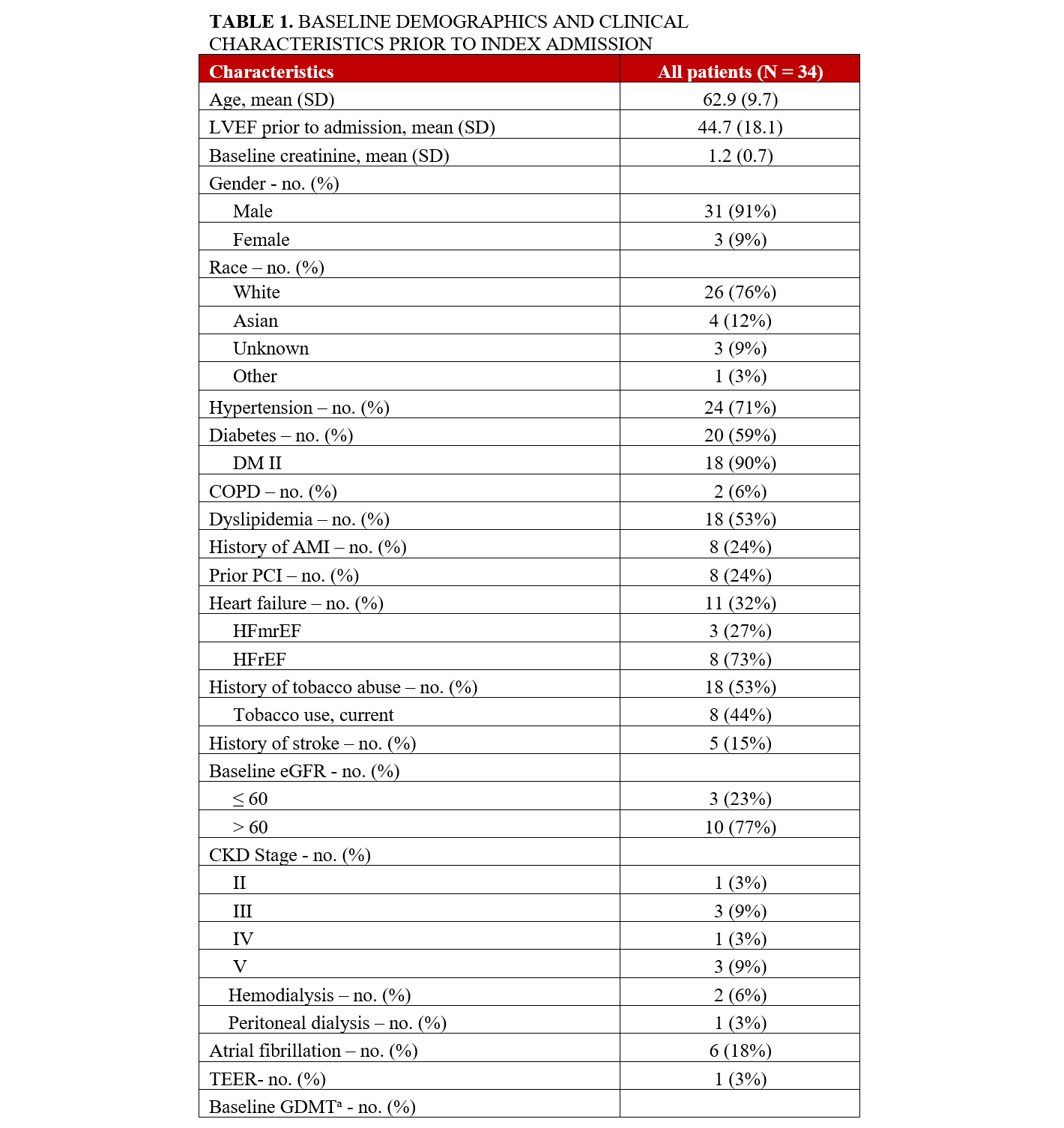

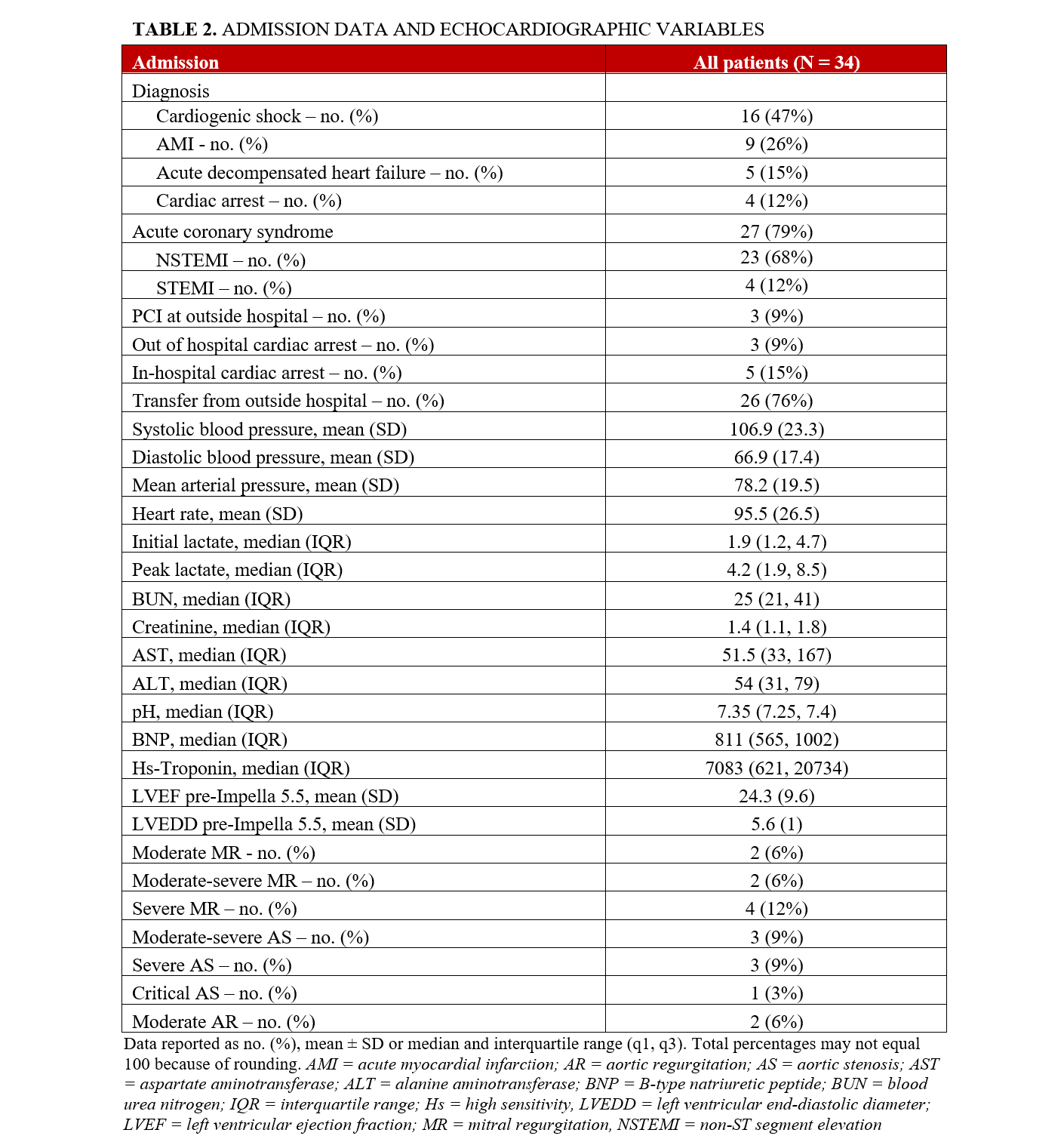

We identified 151 patients who had an Impella 5.5 between January 2021 and December 2024. Out of the 151 patients, 34 (23%) patients underwent Impella 5.5-supported HRPCI. PCI was performed after Impella 5.5 placement in all patients. The mean age of the cohort was 62.9 (± 9.7) years and 91% were male (Table 1). Hypertension (24, 71%), diabetes mellitus (20, 59%), dyslipidemia (18, 53%), and tobacco abuse (18, 53%) were prevalent. The average Charlson Comorbidity Index on admission was 5.3 (± 1.9).

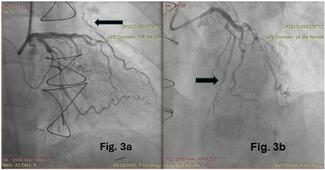

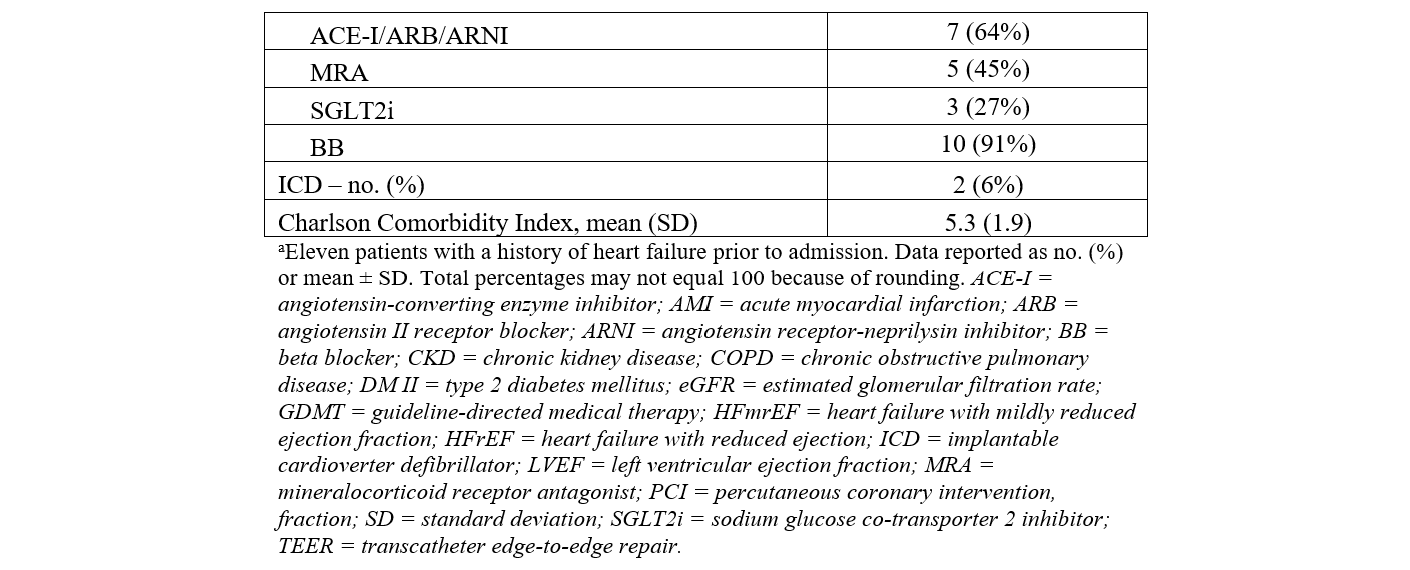

The admission diagnosis was cardiogenic shock (16, 47%), acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (9, 26%), acute decompensated heart failure (5, 15%), and cardiac arrest (4, 12%) (Table 2). Of the 34 patients who underwent Impella 5.5-supported HRPCI, 23 (68%) patients had a non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and 4 (12%) patients had an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) at presentation. Of the 4 patients with STEMI as the admission diagnosis, the times to Impella 5.5 implantation were 4, 14, 17, and 34 hours. Two patients had STEMI as the indication for PCI, and both had an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. One STEMI patient had balloon angioplasty of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) at an outside hospital, was placed on VA-ECMO and Impella CP, and was subsequently transferred to our institution 3 days after the index event. The last STEMI patient was noted to have severe multivessel disease and an LAD that could not be wired; this patient had an IABP placed and was referred for multivessel PCI. Eight (24%) patients experienced cardiac arrest, including 3 out-of-hospital. Most patients (26, 76%) were transferred from another facility. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and mean left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) prior to Impella 5.5 placement were 24.3% and 5.6 cm, respectively.

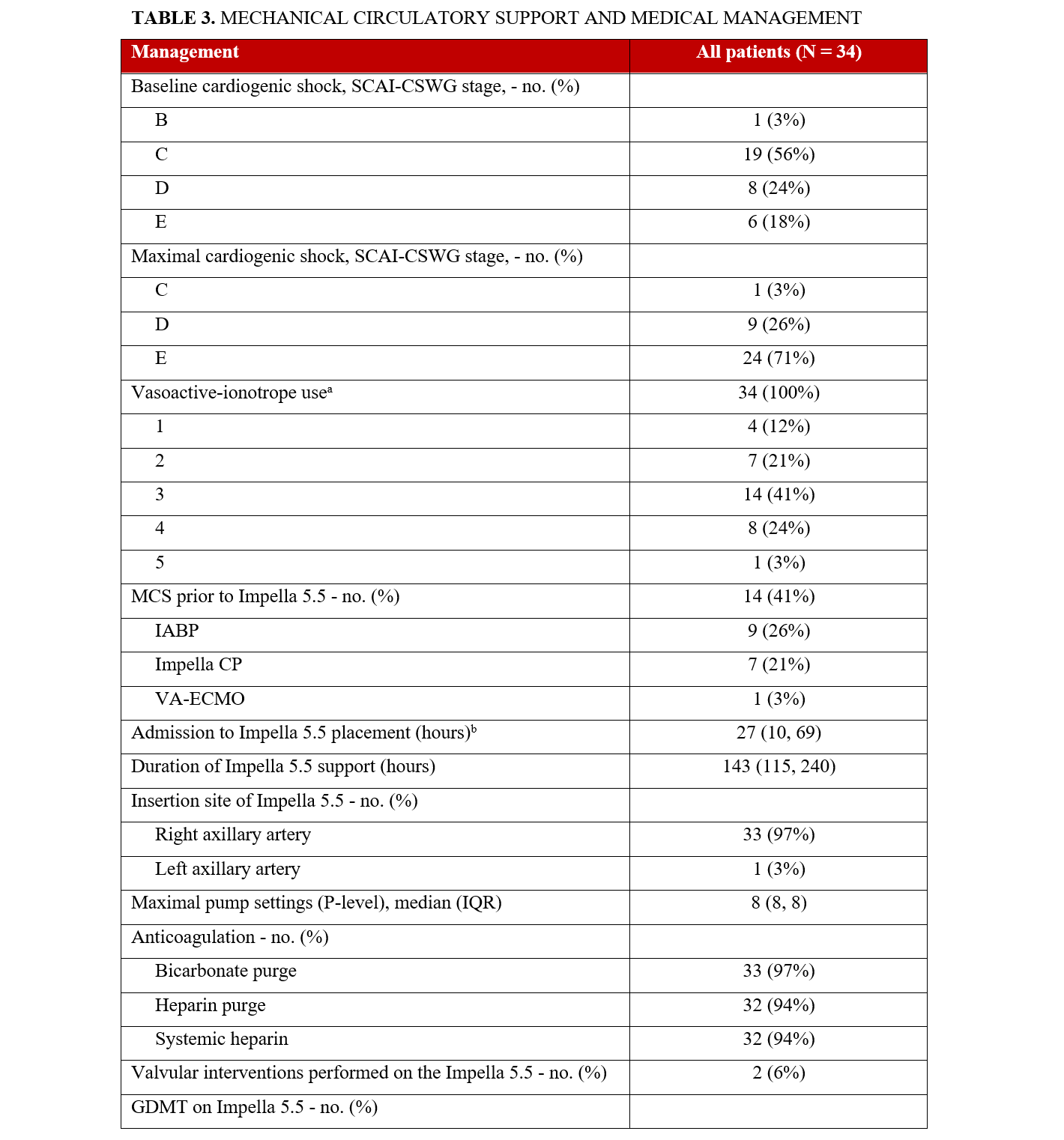

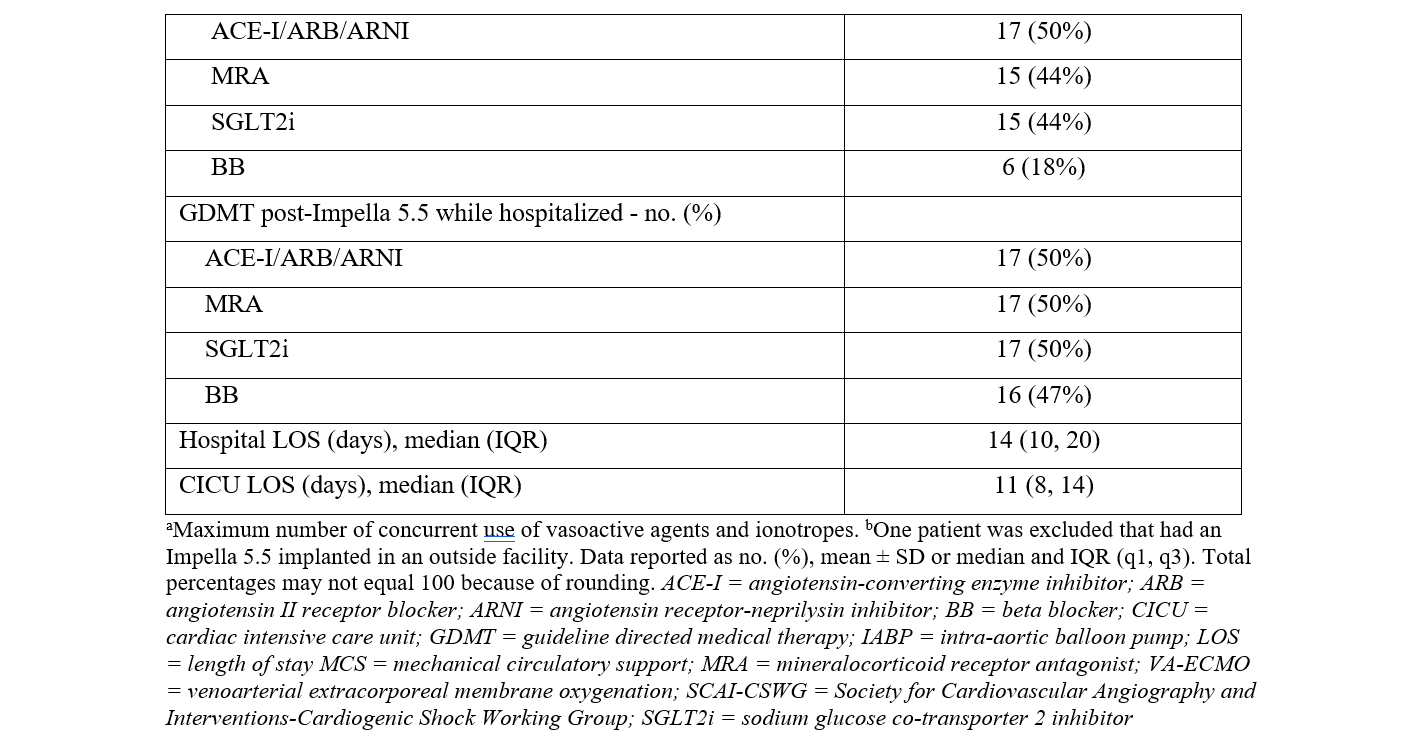

The most common baseline SCAI-CSWG stage was C (19, 56%), followed by stage D (8, 24%) and stage E (6, 18%) (Table 3). The maximal CS stage, however, was predominantly stage E (24, 71%) and stage D (9, 26%). The maximum numbers of vasoactive and inotropic agents used concurrently were 1 (12%), 2 (21%), 3 (41%), 4 (24%), and 5 (3%). Fourteen patients (41%) were treated with other MCS prior to Impella 5.5, including 9 intra-aortic balloon pumps (26%), 7 Impella CP (21%), and 1 VA-ECMO (3%). Patients were transitioned to an Impella 5.5 for a variety of reasons, including the need for a higher level of support (9, 64%), as a bridge to decision for surgical or percutaneous revascularization (4, 29%), and to mitigate the complications associated with prolonged use of a femoral mAFP, such as hemolysis, bleeding, and vascular complications (1, 7%).

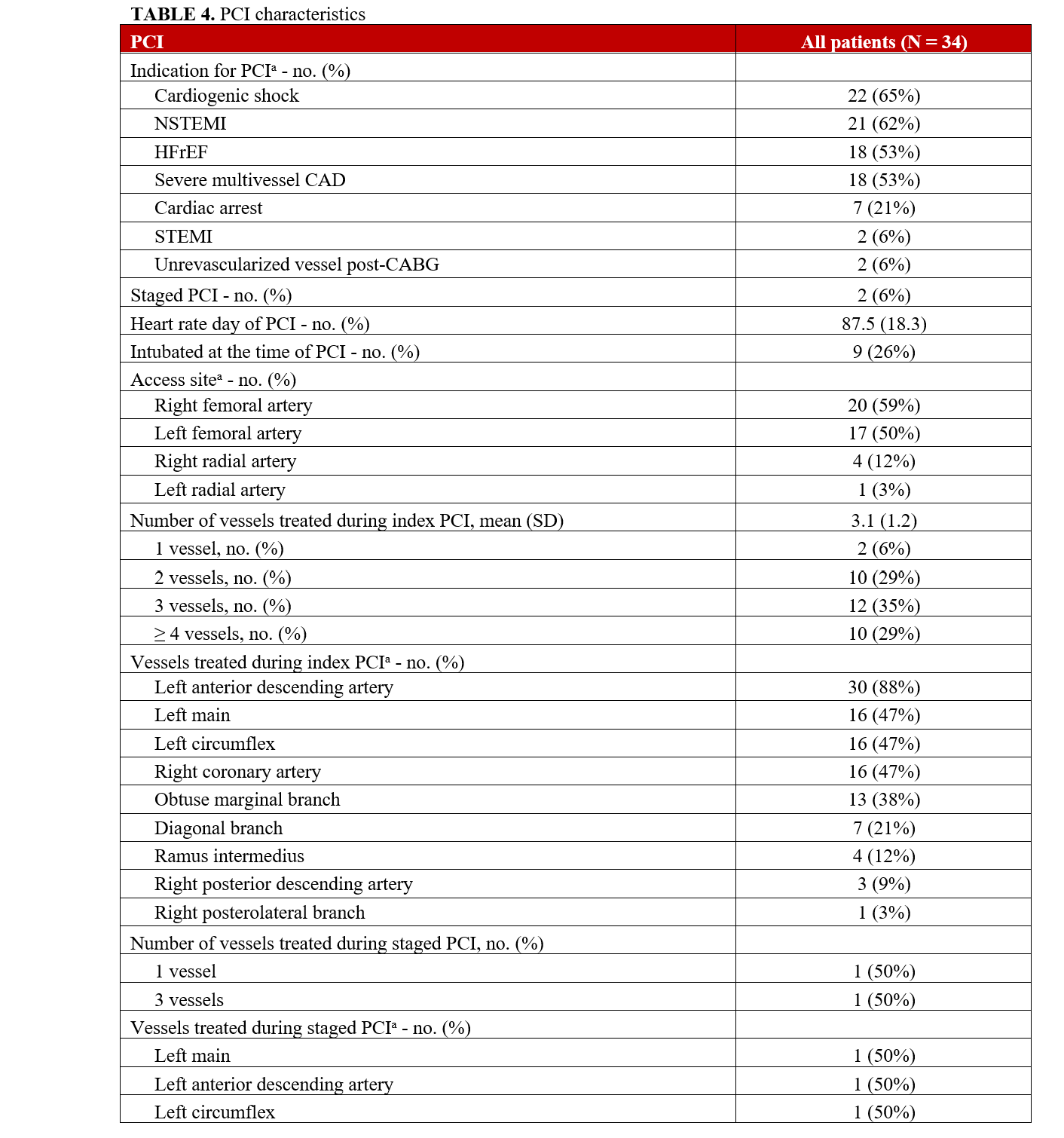

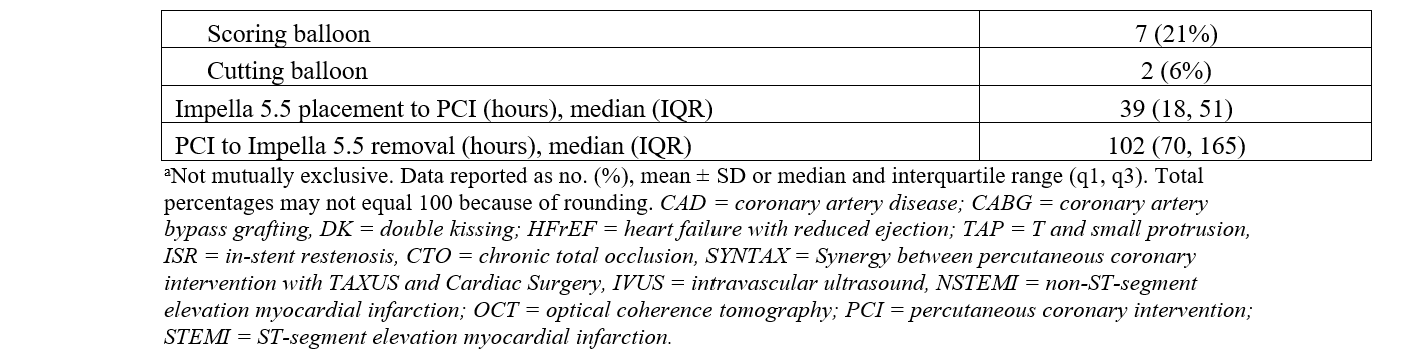

There were 2 transcatheter edge-to-edge repairs done in patients supported with Impella 5.5. Two patients had an aortic valve replacement prior to Impella 5.5 placement during their index hospitalization. All other patients with severe aortic stenosis had balloon aortic valvuloplasty prior to Impella 5.5 placement. The median duration from Impella 5.5 placement to PCI was 39 hours (IQR, 18, 51) (Table 4). The median duration post-PCI to Impella 5.5 explant was 102 hours (IQR, 70, 165). The median duration of Impella 5.5 support was 143 hours (115, 240). The median intensive care unit length of stay (LOS) was 11 days, while the median hospital LOS was 14 days. Guideline-directed medial therapy was initiated in 22 (65%) patients while supported with the Impella 5.5.

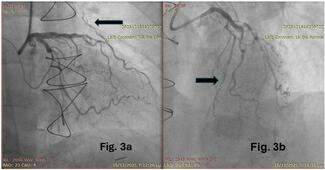

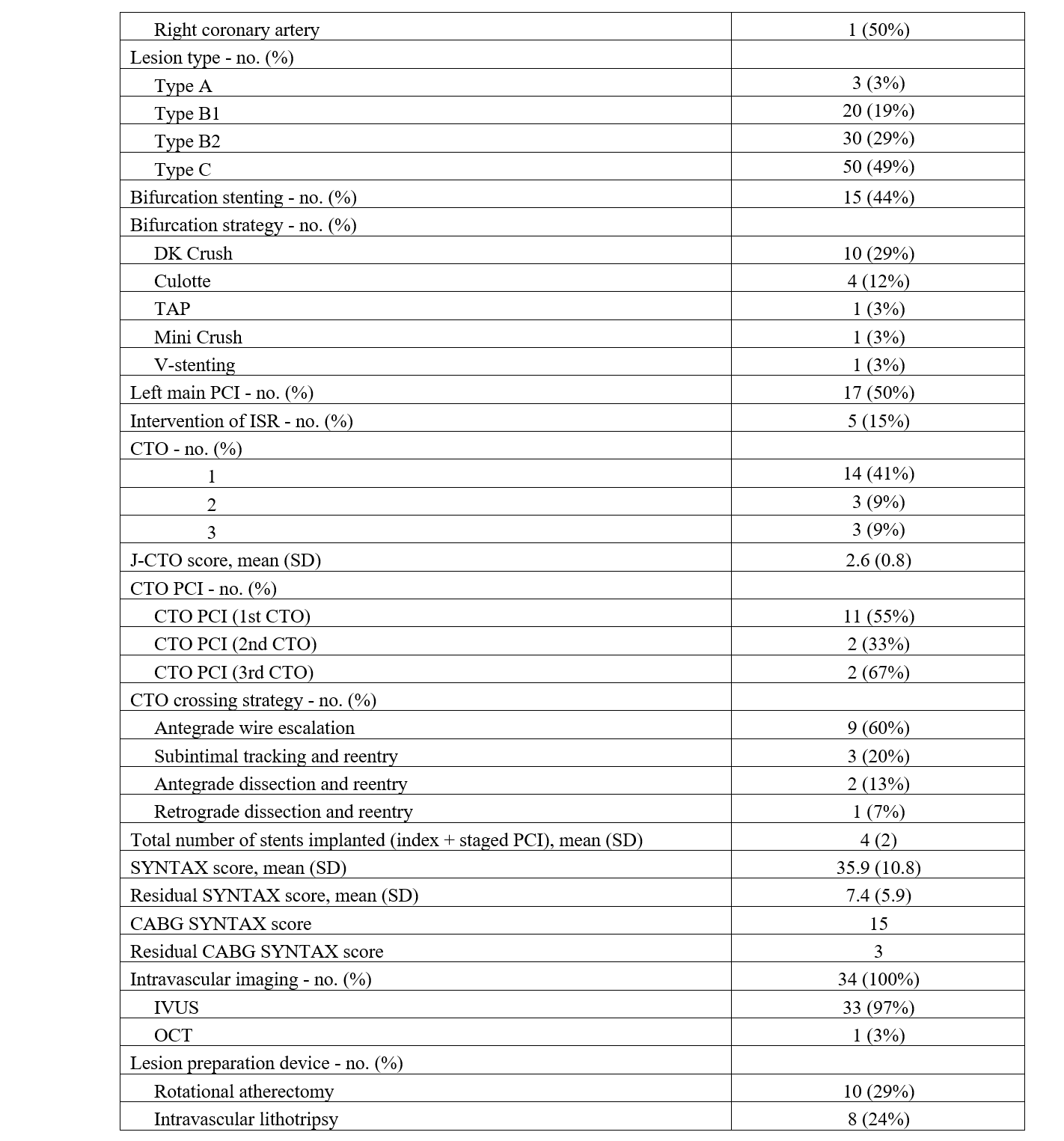

Procedural characteristics are summarized in Table 4. The mean SYNTAX score was 35.9 (± 10.8) and the residual SYNTAX score was 7.4 (± 5.9). All patients were determined to be at prohibitive risk for surgical revascularization after multidisciplinary assessment, and 94% of patients required multivessel PCI. Left-main PCI was performed in 50% (17) of the study population. The lesion severity was very complex: 49% (50) of the coronary artery lesions that were intervened on were type C lesions and 29% (30) were type B2 lesions. Two patients required PCI of surgically un-revascularized native vessels 2 and 3 days post-CABG. One patient did not have angiography of surgical grafts and was excluded from the CABG SYNTAX calculation. The other patient had a CABG SYNTAX score of 15 and a residual CABG SYNTAX score of 3.

The access site for PCI was primarily the femoral artery (37, 88%), and dual access was utilized in 24% of patients. Bifurcation stenting was performed in 44% of the study population. CTOs were prevalent, with 29 CTOs in 20 (59%) patients with an average J-CTO score of 2.6. Fourteen (41%) patients had 1 CTO, 3 (9%) patients had 2 CTOs, and 3 (9%) patients had 3 CTOs. CTO PCI was attempted in 59% of lesions, with an angiographic success rate of 88%. Antegrade wire escalation (AWE) was the most successful crossing strategy (9, 60%), followed by subintimal tracking and reentry (3, 20%) and antegrade dissection and reentry (2, 13%). One (7%) patient was successfully crossed with retrograde dissection and reentry. The mean number of stents implanted per patient was 4 (± 2).

Intravascular imaging was utilized in all patients. Intravascular ultrasound was used 97% of the time, and optical coherence tomography was used in 1 (3%) patient. The most common adjunctive lesion preparation device used was rotational atherectomy (10, 29%), followed by intravascular lithotripsy (8, 24%), scoring balloon (7, 21%), and cutting balloon (2, 6%).

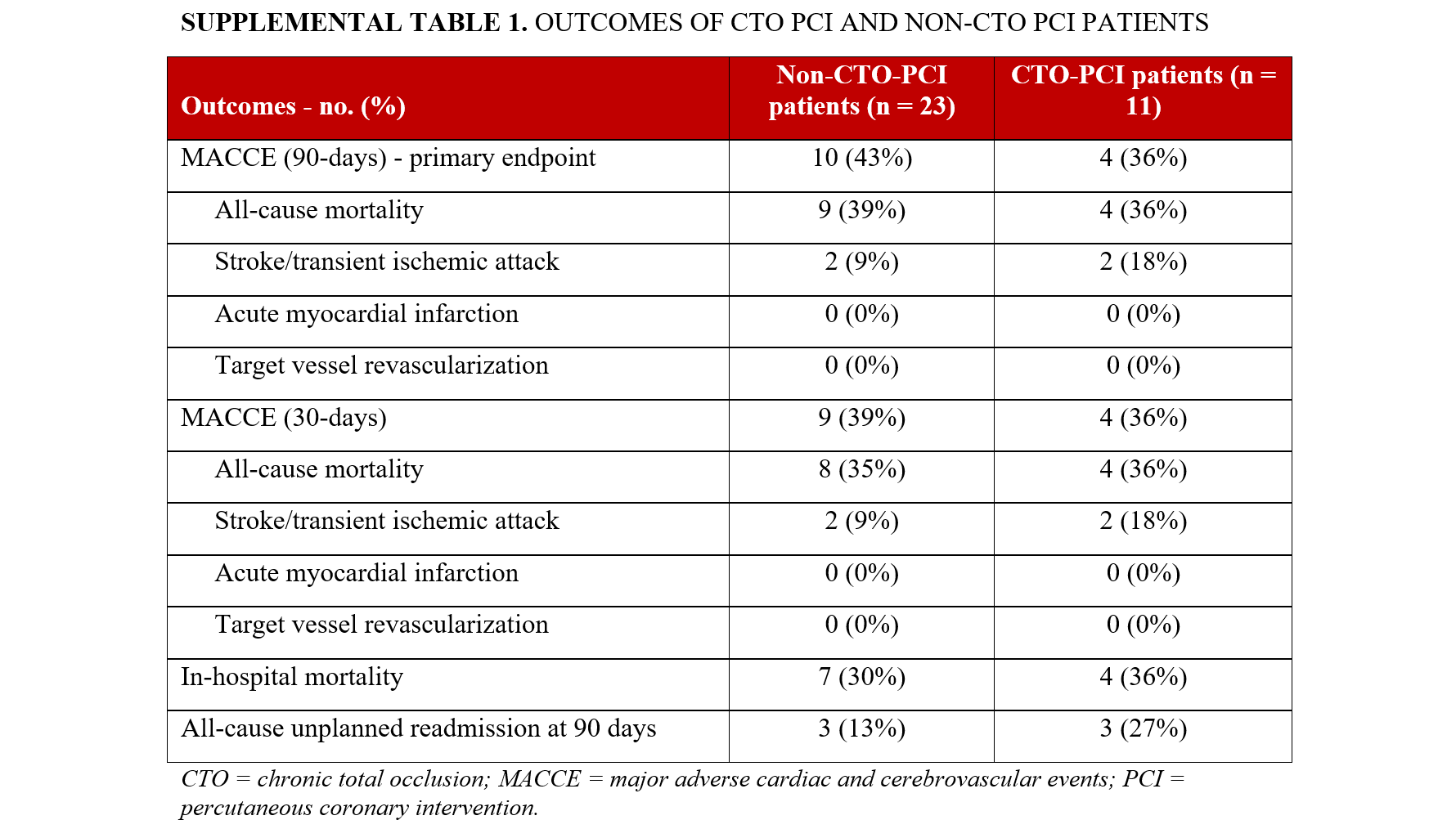

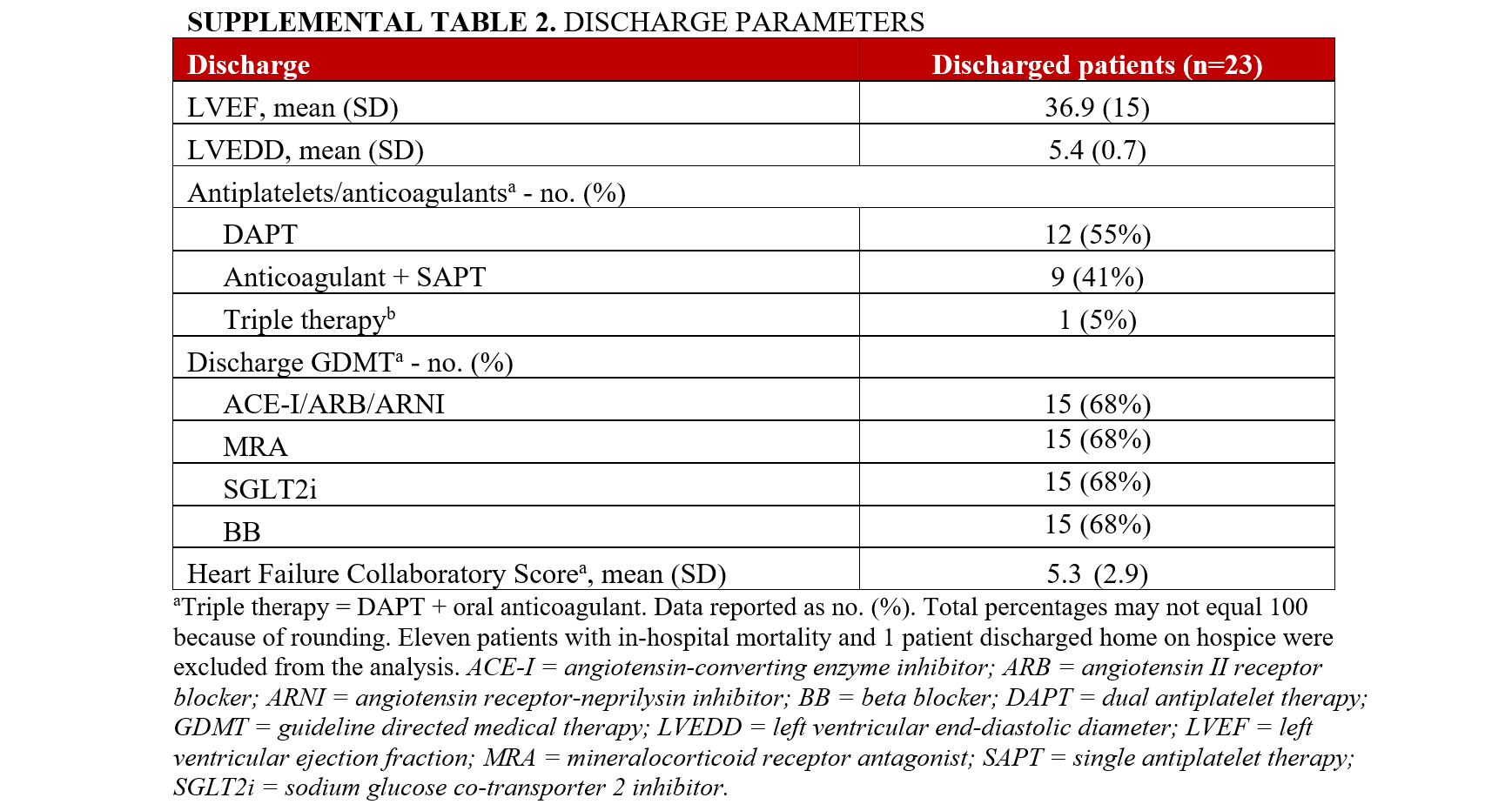

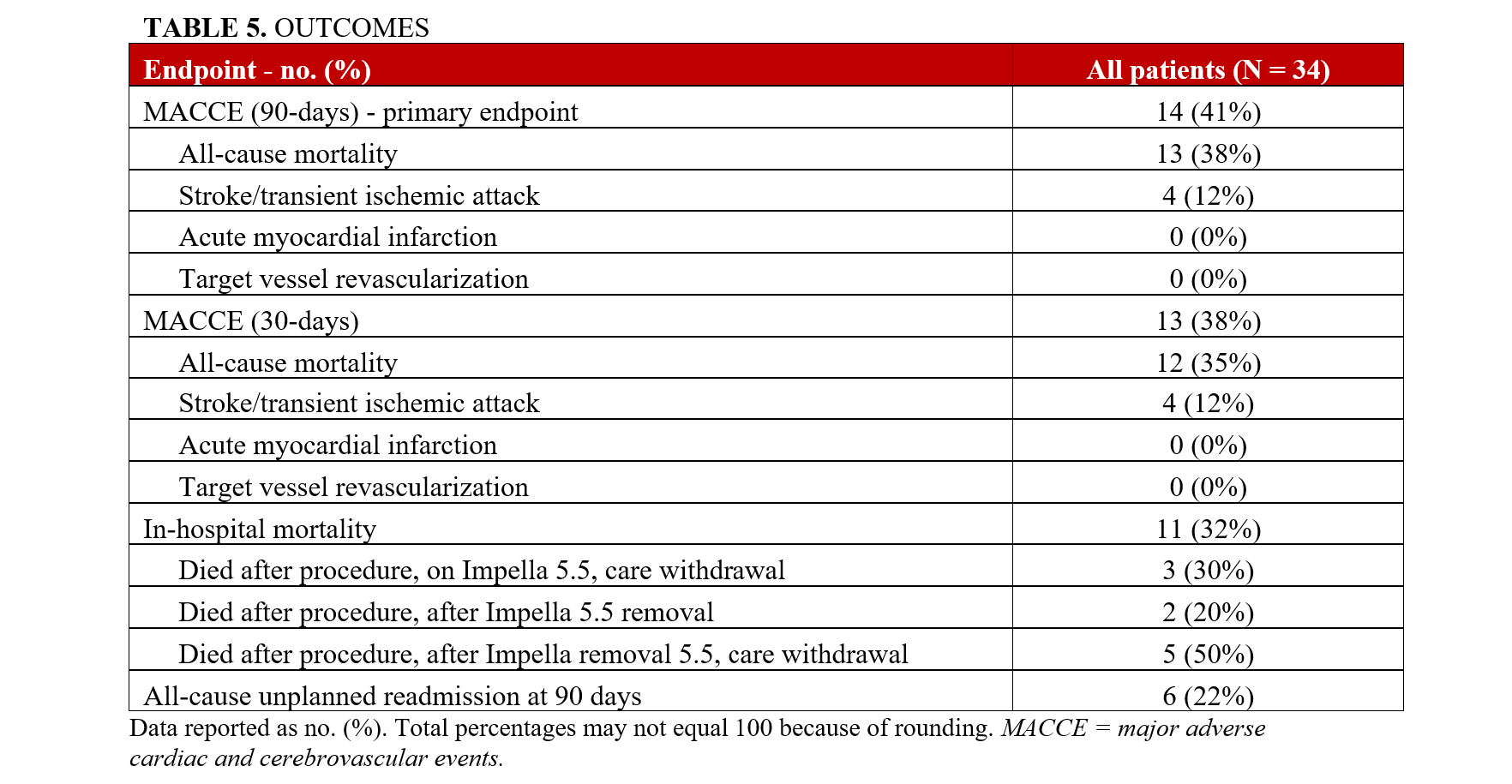

MACCE occurred in 41% (14) of the patients (Table 5). In-hospital mortality was 32% (11); however, there was no intraprocedural death. The all-cause mortality after 30 and 90 days was 35% (12) and 38% (13). There was no AMI or target vessel revascularization after 90 days. The all-cause unplanned readmission at 90 days was 22% (6). MACCE was similar in the CTO-PCI and the non-CTO PCI cohorts (Supplemental Table 1). The mean HFCS on discharge was 5.3 (± 2.9) (Supplemental Table 2). There was improvement of the LVEF prior to discharge. The mean LVEF on discharge was 36.9 (± 15) (Supplemental Table 2).

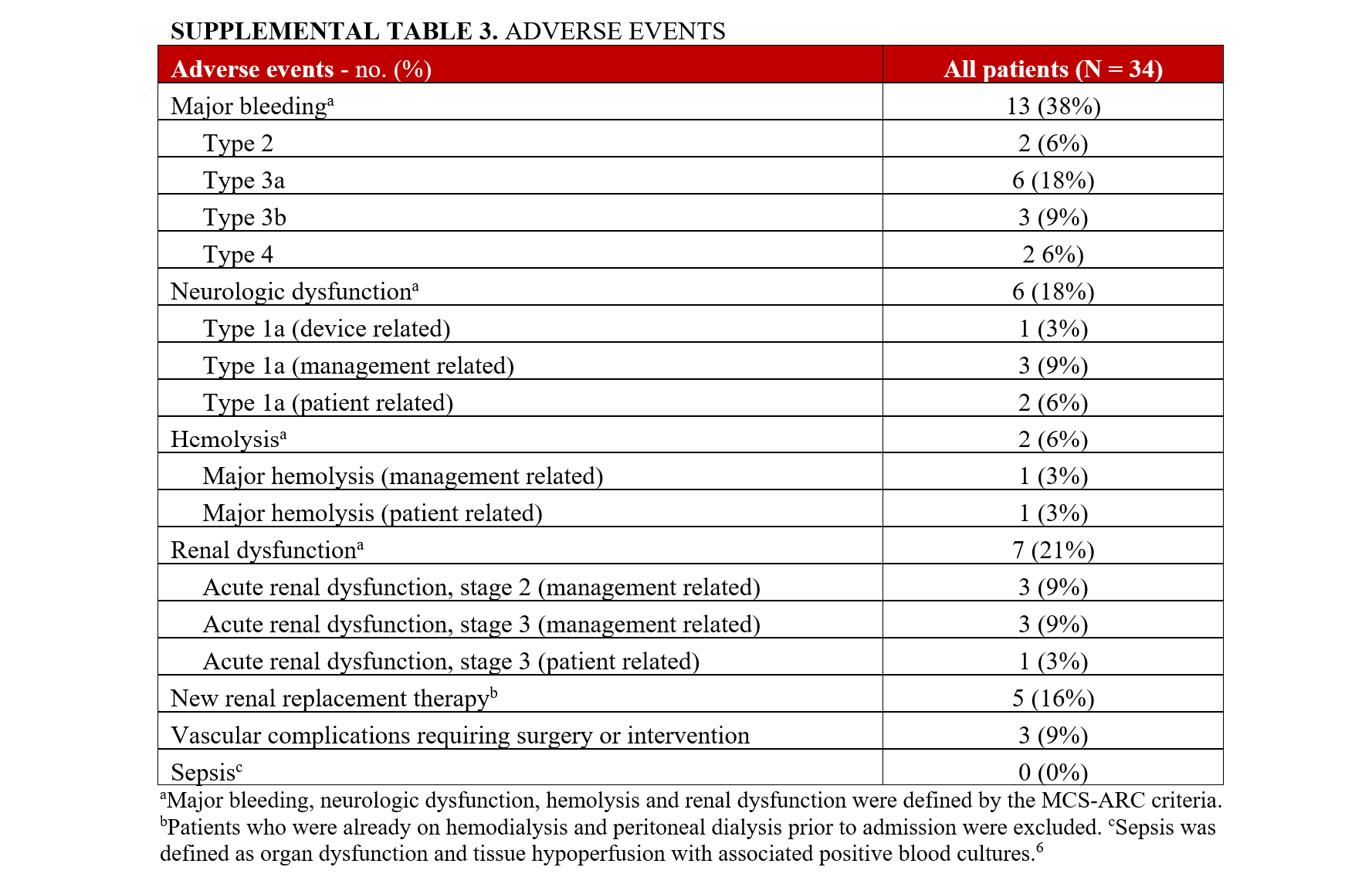

Major bleeding occurred in 13 (38%) patients, and the most common were type 3a (6, 18%) and type 3b (3, 9%) bleeding adverse events requiring blood transfusion (Supplemental Table 3). Bleeding events were primarily due to gastrointestinal bleeding, epistaxis, and procedure-related bleeding, including access site bleeding. There were 2 (6%) device-related bleeding events at the insertion site that required surgical intervention. However, there were no fatal bleeding events.

Major hemolysis occurred in 2 (6%) patients; 1 was patient-related due to a pre-existing LV thrombus, and the other was device-related. Five (16%) patients had a new requirement of dialysis during their hospitalization; 2 of these patients had recovery of their renal function prior to discharge, and 2 patients had an in-hospital mortality. One patient was initiated on dialysis a few days before Impella 5.5 placement and continued to require dialysis 90 days post-procedure. There were no reported episodes of sepsis.

Discussion

In this single-center report, we describe the clinical, procedural, anatomic characteristics, and outcomes of patients undergoing HRPCI while supported by an Impella 5.5. The major findings of our study are that Impella 5.5 is feasible and effective to support HRPCI in patients with late stages of CS. Patients had significant underlying multivessel CAD, as evidenced by high baseline SYNTAX scores, and underwent complex and extensive revascularization. The mean SYNTAX score was 35.9 (± 10.8), the lesion complexity was high, and left-main PCI was performed on 50% of patients. Rates of hemolysis and acute kidney injury (AKI) requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT) were lower than previous trials of femoral mAFP in CS.6 The 30- and 90-day mortality rates were lower than previously published mortality rates despite the degree of CS.6,8,9

Although CS was not an inclusion criterion, CS was prevalent and the distribution of baseline SCAI-CSWG stages in our cohort was similar to previous randomized trials that have investigated the use of MCS in AMICS.6,9 In the ECLS trial, the baseline CS stages were C (53.4%), D (8.7%), and E (38%).9 In the DanGer shock trial, the baseline SCAI-CSWG stages were C (55.9%), D (28.5%), and E (15.6%).6 In our study cohort, most (97%) patients had a maximal SCAI-CSWG stage D-E, underscoring the severity of illness of the study population.

PCI was very complex, as reflected by the high ACC/AHA lesion classification and very high J-CTO and SYNTAX scores. In a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of 54 patients who underwent HRPCI supported by a percutaneous left atrial-femoral artery bypass pump (TandemHeart), the median SYNTAX score was 33.22 Awar et al found that the mean SYNTAX score was 32 ± 11 in patients who underwent ECMO-supported HRPCI.23 In the PROTECT II and PROTECT III studies, the mean SYNTAX scores were 30.3 ± 13.1 and 28.0 ± 12.6, respectively, in the mAFP group.1,24 In our study, the mean SYNTAX score was higher (35.9 ± 10.8). The lesion complexity was also very high; 78% of the PCI lesions were type B2 or C lesions.

In a multicenter observational national registry in Italy that evaluated the use of mAFP for HRPCI, left-main PCI was performed in 48% of the study population and the mean number of vessels treated was 1.9 ± 0.9.3 In the PROTECT II and PROTECT III trials, left-main PCI was performed in 28.2% and 43.3%, respectively.24 In PROTECT III, the mean number of vessels treated was 2.1 ± 0.7.24 In our study, unprotected left-main PCI was performed in 50% of the patients and the mean number of treated vessels was 3.2 (± 1.3). CTOs were prevalent in our study; 59% of our study population had a CTO compared with 8.8% in PROTECT II and 13.6% in PROTECT III.24 The mean J-CTO score was 2.6 (± 0.8). Of the CTOs attempted, revascularization was successful in 88%, with the majority treated with antegrade crossing strategies. Intracoronary imaging was utilized for procedural guidance in all patients.

Major bleeding was the most common reported adverse event (38%). In IABP-SHOCK II, life threatening or severe bleeding occurred in 3.3% of patients and moderate bleeding occurred in 17.3% of patients.8 Similar rates of bleeding were observed in the ECMO group (23.4%) in ECLS shock and in the mAFP group (21.8%) in DanGer shock.6,9 While the overall bleeding rate was higher than previously published shock trials, device-related bleeding requiring intervention only occurred in 6% of the patients in our study, and there were no fatal bleeding events.

Major hemolysis was low (6%) and significantly less than was seen in the Impella CP-supported DanGer trial (12.4%), despite a much longer duration of support seen in our case series (143 vs 59 hours).6 The CSWG reported that in patients supported with Impella 5.0/5.5, hemolysis occurred in 22% of patients and there was a new requirement of RRT for acute renal failure in 35.1% of patients.10 In our study, acute renal dysfunction occurred in 21% of the study population, and 16% of patients not previously on dialysis required RRT. The lower incidence of hemolysis and need for RRT despite much longer duration of support suggests that hemodynamic support with Impella 5.5, as opposed to Impella CP, may be a preferred strategy for patients requiring higher levels or longer duration of support.

The incidence of Type 1a MCS-ARC neurologic dysfunction in our study was 18%; however, only 1 (3%) patient had a neurologic dysfunction that was device-related. The etiology of the cerebrovascular accidents in our study was secondary to atherosclerosis, cardioembolic process in the setting of severe LV dysfunction, and the development of a new LV thrombus after Impella 5.5 placement, as well as postprocedural complication from a transcatheter aortic valve replacement with concurrent Impella 5.5 replacement.

MACCE occurred in 41% of our study cohort at 90 days, driven primarily by all-cause mortality and stroke/transient ischemic attack. In the IABP group in IABP-SHOCK II, the 30-day all-cause mortality was 39.7%; in the ECMO group in ECLS, it was 47.8%.8,9 In DanGer, the 180-day all-cause mortality was 45.8% in the mAFP group.6 In our study, the 30-day all-cause mortality was 35%, and the 90-day all-cause mortality was 38%.

The overall median duration from Impella 5.5 placement to HRPCI was 39 hours (18, 51) in our study, reflecting the collaborative process of the multidisciplinary heart team approach to stabilize the patient, determine the right revascularization strategy, and ensure successful completion of PCI within a few days.

Limitations

Our study has limitations inherent to its retrospective design. First, data extraction was limited by the documentation of the variables in the electronic medical record. Second, the study population was homogenous (91% white, 76% male), which may limit generalizability. Third, all procedures were performed at a quaternary medical center by providers with extensive experience with HRPCI and both surgical implantation and long-term management of the Impella 5.5 pump. It is possible the results are not generalizable to centers with limited experience. Fourth, PCI was performed by 7 interventionalists, though 68% were done by 1 interventionalist. Thus, there was no standardized interventional approach. Lastly, the acute—and often unstable—nature of the patient presentation precluded routine use of viability testing.

Conclusions

The use of Impella 5.5 to support HRPCI is feasible in patients with cardiogenic shock, heart failure, and very advanced CAD. Further research is needed to ascertain the relative benefits compared with other temporary MCS devices for HRPCI in CS.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Olufemi Olorunda, MD, MPH1; Jason Wollmuth, MD2; Hsin-Fang Li, PhD2; Jacob Abraham, MD2

From the 1Division of Cardiology, Samaritan Health Services, Corvallis, Oregon; 2Center for Cardiovascular Analytics, Research, and Data Science, Providence-St. Joseph Research Network, Portland, Oregon.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Corrin Murphy and Jannate Ahmed for the technical assistance and administrative support provided for the manuscript.

Disclosures: Dr Olorunda holds common stock in Pfizer. Dr Wollmuth is a consultant/speaker for Abbott Vascular, Shockwave, Abiomed, and Boston Scientific. Dr Abraham is an employee of Edwards Lifesciences and receives honoraria from Abbott and Abiomed/J&J Medtech. Dr Li reports no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Address for correspondence: Jacob Abraham, MD, 9427 Southwest Barnes Road, Suite 594. Portland, OR 97225, USA. Email: Jacob.Abraham@providence.org

References

- O'Neill WW, Kleiman NS, Moses J, et al. A prospective, randomized clinical trial of hemodynamic support with Impella 2.5 versus intra-aortic balloon pump in patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: the PROTECT II study. Circulation. 2012;126(14):1717-1727. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.098194

- Pietrasik A, Gąsecka A, Pawłowski T, et al. Multicenter registry of Impella-assisted high-risk percutaneous coronary interventions and cardiogenic shock in Poland (IMPELLA-PL). Kardiol Pol. 2023;81(11):1103-1112. doi:10.33963/v.kp.97218

- Chieffo A, Ancona MB, Burzotta F, et al. Observational multicentre registry of patients treated with IMPella mechanical circulatory support device in ITaly: the IMP-IT registry. EuroIntervention. 2020;15(15):e1343-e1350. doi:10.4244/EIJ-D-19-00428

- Zein R, Patel C, Mercado-Alamo A, Schreiber T, Kaki A. A review of the Impella devices. Interv Cardiol. 2022;17:e05. doi:10.15420/icr.2021.11

- Glazier JJ, Kaki A. The Impella device: historical background, clinical applications and future directions. Int J Angiol. 2019;28(2):118-123. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1676369

- Møller JE, Engstrøm T, Jensen LO, et al; DanGer Shock Investigators. Microaxial flow pump or standard care in infarct-related cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(15):1382-1393. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2312572

- Sterling LH, Fernando SM, Talarico R, et al. Long-term outcomes of cardiogenic shock complicating myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82(10):985-995. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.06.026

- Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann FJ, et al; IABP-SHOCK II Trial Investigators. Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(14):1287-1296. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1208410

- Thiele H, Zeymer U, Akin I, et al; ECLS-SHOCK Investigators. Extracorporeal life support in infarct-related cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(14):1286-1297. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2307227

- Fried J, Farr M, Kanwar M, et al. Clinical outcomes among cardiogenic shock patients supported with high-capacity Impella axial flow pumps: a report from the Cardiogenic Shock Working Group. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2024;43(9):1478-1488. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2024.05.015

- Ramzy D, Soltesz E, Anderson M. New surgical circulatory support system outcomes. ASAIO J. 2020;66(7):746-752. doi:10.1097/MAT.0000000000001194

- Ramzy D, Anderson M, Batsides G, et al. Early outcomes of the first 200 US Patients treated with Impella 5.5: a novel temporary left ventricular assist device. Innovations (Phila). 2021;16(4):365-372. doi:10.1177/15569845211013329

- Kapur NK, Kanwar M, Sinha SS, et al. Criteria for defining stages of cardiogenic shock severity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(3):185-198. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.04.049

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

- John KJ, Stone SM, Zhang Y, et al. Application of Cardiogenic Shock Working Group-defined Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (CSWG-SCAI) Staging of Cardiogenic Shock to the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) database. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2023;57:82-90. doi:10.1016/j.carrev.2023.06.019

- Fiuzat M, Hamo CE, Butler J, et al. Optimal background pharmacological therapy for heart failure patients in clinical trials: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(5):504-510. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.11.033

- Sianos G, Morel MA, Kappetein AP, et al. The SYNTAX Score: an angiographic tool grading the complexity of coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention. 2005;1(2):219-227

- Farooq V, Girasis C, Magro M, et al. The CABG SYNTAX Score - an angiographic tool to grade the complexity of coronary disease following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: from the SYNTAX Left Main Angiographic (SYNTAX-LE MANS) substudy. EuroIntervention. 2013;8(11):1277-1285. doi:10.4244/EIJV8I11A196

- Ellis SG, Vandormael MG, Cowley MJ, et al. Coronary morphologic and clinical determinants of procedural outcome with angioplasty for multivessel coronary disease. Implications for patient selection. Multivessel Angioplasty Prognosis Study Group. Circulation. 1990;82(4):1193-1202. doi:10.1161/01.cir.82.4.1193

- Morino Y, Abe M, Morimoto T, et al; J-CTO Registry Investigators. Predicting successful guidewire crossing through chronic total occlusion of native coronary lesions within 30 minutes: the J-CTO (Multicenter CTO Registry in Japan) score as a difficulty grading and time assessment tool. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4(2):213-221. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2010.09.024

- Kormos RL, Antonides CFJ, Goldstein DJ, et al. Updated definitions of adverse events for trials and registries of mechanical circulatory support: a consensus statement of the mechanical circulatory support academic research consortium. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39(8):735-750. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.010

- Alli OO, Singh IM, Holmes DR Jr, Pulido JN, Park SJ, Rihal CS. Percutaneous left ventricular assist device with TandemHeart for high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: the Mayo Clinic experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;80(5):728-734. doi:10.1002/ccd.23465

- Awar L, Song AJ, Dhillon AS, Mehra A, Burstein S, Shavelle DM. Use of the CardioHELP device for temporary hemodynamic support during high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention. J Invasive Cardiol. 2021;33(8):E614-E618. doi:10.25270/jic/20.00652

- O'Neill WW, Anderson M, Burkhoff D, et al. Improved outcomes in patients with severely depressed LVEF undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with contemporary practices. Am Heart J. 2022;248:139-149. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2022.02.006