A Challenging Case of Left Main Chronic Total Occlusion and the Reverse T-Stenting and Small Protrusion (TAP) Technique: Success With the Investment Strategy

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2026. doi:10.25270/jic/26.00009. Epub January 26, 2026.

A 62-year-old man with a history of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) (left internal mammary artery [LIMA] to left anterior descending artery [LAD], left radial artery graft to right coronary artery ([RCA]) was referred to our center because of worsening anginal symptoms despite being on optimal antianginal medical therapy (metoprolol 50 mg twice daily, isosorbide mononitrate 20 mg once daily). Physical examination, electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, and routine laboratory tests were normal, with negative cardiac enzyme values.

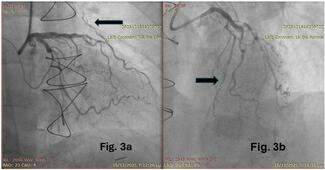

Coronary angiography revealed total occlusion of both the left coronary artery and the RCA at their ostial origins (Figure 1A and B). The LIMA graft showed severe stenosis (90%) at the anastomotic end (Figure 1C), while the radial artery graft to the distal RCA was patent (Figure 1D). Interestingly, the LIMA graft was anastomosed to a major diagonal branch rather than the LAD (Video 1).

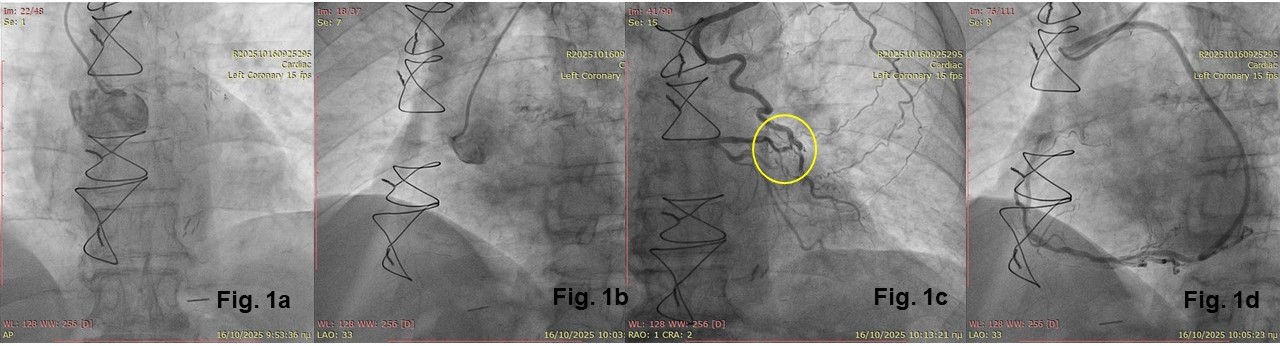

According to patient preference, we proceeded with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of the left main (LM) chronic total occlusion (CTO). The CTO procedure setup included bi-ulnar access under ultrasound guidance, a 7F 3.5 CLS guiding catheter at the ostium of the LM, and a 6F IMA guiding catheter at the LIMA. Antegrade wiring escalation technique with a Gaia Second (ASAHI INTECC) (Figure 2A) and a Turnpike Spiral microcatheter (Teleflex) support was successful, with the antegrade wire advancing through the proximal LAD to the major diagonal branch (Figure 2B). The Gaia Second guidewire was then exchanged for a workhorse wire.

After predilation of the LM and proximal LAD, multiple attempts were made to wire the left circumflex artery (LCX) using a dual microcatheter system (ReCross [IMDS] initially, followed by a SASUKE [ASAHI INTECC]) (Figure 2C). A 2-stent technique, the reverse T-stenting and small protrusion (TAP) technique, was then employed. In this technique, a stent is first inflated at the side branch (here, the LCX) while simultaneously inflating a 1:1 noncompliant balloon at the major branch. Minimal stent strut protrusion does not require rewiring (Figure 2D and E). A second stent is then placed from the LM to the LAD (Figure 2F). Rewiring, kissing balloon inflation, and the proximal optimization technique follow, completing the LM stenting (Video 2).

Incomplete filling of the distal LAD was observed, which appeared to be partially occluded more distally (Figure 2G). The ulnar artery remained patent after PCI, as shown by forearm angiography (Figure 2H). The procedure was intentionally stopped after balloon dilation of the proximal part of the LAD and the diagonal and scheduled for completion after 4 to 8 weeks. This staged approach, called the investment CTO strategy, has been shown to be safe and more effective than the standard 1-stage CTO procedure in difficult CTO cases.

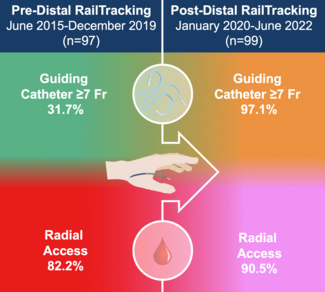

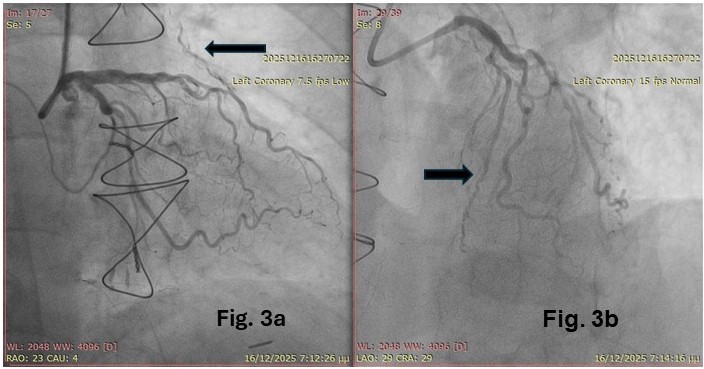

The second-stage PCI was performed via the right ulnar artery again. This revealed an open LAD (Figure 3B), despite its previous appearance of occlusion, while the LIMA graft now appeared diffusely narrowed (string sign) (Figure 3A). Dilation of the proximal LAD and stent placement concluded the second procedure (Video 3). The patient was discharged the next day without complications and remained asymptomatic at the 2-month follow-up.

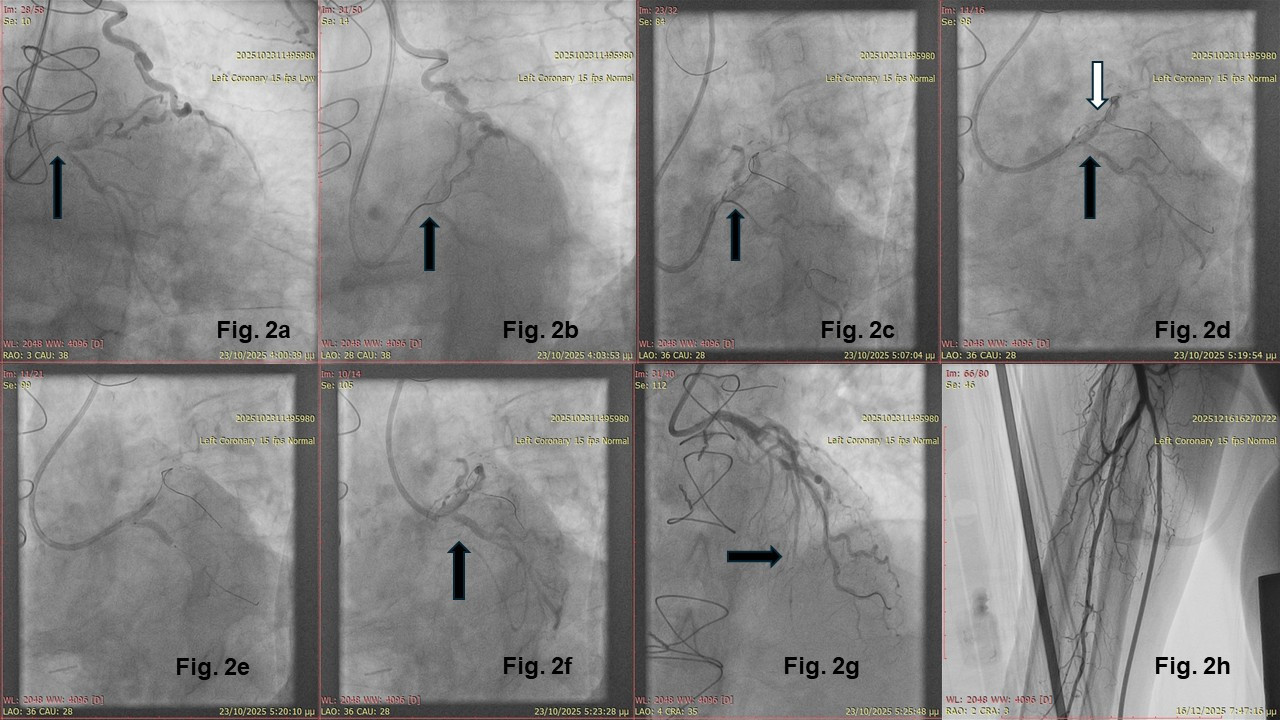

LM-CTO PCI is feasible but demanding and uncommon (~0.6% of CTO PCIs) and should only be performed by experienced operators. It is usually performed in patients with previous CABG and potential LIMA graft failure.1 Bi-ulnar access, even in patients with a harvested ipsilateral radial artery, is safe, especially under ultrasound guidance, and can help avoid femoral artery complications.2 The investment CTO strategy increases overall success rates (> 90%) and reduces complication risk.3-5 In addition, reverse TAP is noninferior to the double-kissing crush technique in LM bifurcation PCI.6

Affiliations and Disclosures

Konstantinos Filippou, MD1; Konstantinos Manousopoulos, MD1; Panagiotis Varelas, MD1; Dimitrios Karelas, MD1; Ioannis Kouloulias, MD1; Alexandros Zaraggas, MD1; Ioannis Papadopoulos, MD1; Ioannis Nenekidis, MD, PhD2; Ioannis Tsiafoutis, MD, PhD1

From the 12nd Cardiology department General Hospital Korgialeneio Mpenakeio- Hellenic Red Cross, Greece; 21st Cardiothoracic and Heart Transplant Unit, Onassio Cardiac Surgery Center, Kallithea, Athens, Greece.

Disclosures: The authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Consent statement: The authors confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report, including image(s) and associated text, has been obtained from the patient in line with the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) guidance.

Address for correspondence: Konstantinos Filippou, MD, Hemodynamic Department, General Hospital Korgialeneio Mpenakeio-Hellenic Red Cross, 11145 Nikolaidou Street, Athens 11526, Greece. Email: filippakos.kos@gmail.com

References

- Strepkos D, Alexandrou M, Mutlu D, et al. Outcomes of left main chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;105(1):23-31. doi:10.1002/ccd.31289

- Kedev S, Zafirovska B, Dharma S, Petkoska D. Safety and feasibility of transulnar catheterization when ipsilateral radial access is not available. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;83(1):E51-E60. doi:10.1002/ccd.25123

- Øksnes A, Skaar E, Engan B, et al. Effectiveness, safety, and patient reported outcomes of a planned investment procedure in higher-risk chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention: rationale and design of the invest-CTO study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;102(1):71-79. doi:10.1002/ccd.30692

- Kladou E, Strepkos D, Alexandrou M, et al; PROGRESS‐CTO Investigators. Modification procedures for chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the PROGRESS-CTO registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;106(7):3628-3639. doi:10.1002/ccd.70228

- Xenogiannis I, Choi JW, Alaswad K, et al. Outcomes of subintimal plaque modification in chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;96(5):1029-1035. doi:10.1002/ccd.28614.

- Olschewski M, Ullrich H, Knorr M, et al. Randomized non-inferiority TrIal comParing reverse T And Protrusion versus double-kissing and crush Stenting for the treatment of complex left main bifurcation lesions. Clin Res Cardiol. 2022;111(7):750-760. doi:10.1007/s00392-021-01972-2