Clinical Predictors of Long-Term Atrial Fibrillation Recurrence Post Catheter Ablation: An ITHACA-Database Analysis

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2026. doi:10.25270/jic/25.00273. Epub January 12, 2026.

Abstract

Objectives. Shared decision making regarding how to best manage atrial fibrillation (AF) includes the use and efficacy of catheter ablation (CA) as a treatment option. However, the long-term success rate for the procedure based on patients’ baseline demographics and comorbidities remains unclear. The authors aimed to create a user-friendly predictive model to help provide an individualized risk score for long-term AF recurrence.

Methods. Ablation outcomes reported in the electronic medical records were documented from 3, 12, and 24 months, and last follow-up visit, which was an average of 42 months. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify independent variables associated with AF recurrence. Based on respective coefficients, associated variables were used to create the ORACLE-AF (symptOmatic AF, race [White], AF type [persistent], cardioversion, late age > 70, early AF recurrence, asthma/COPD, heart failure) model. A k-1 machine learning model was used for validation, using an 80/20 development test cohort ratio.

Results. A total of 3440 patients (69.4 ± 10.2 years, 44% women) who received a de novo CA were included in the analysis. Forty-eight percent of patients had the primary composite outcome of AF recurrence by the end of the 42-month observation period. After analysis, the ORACLE-AF model was created with an area under the curve of 0.80.

Conclusions. Using machine learning, the authors created a predictive tool to allow for individualized risk prediction for long-term AF recurrence following CA. These findings highlight the need to consider risk factors not typically associated with long-term AF recurrence during the pre-ablation consultation.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most prevalent arrhythmia globally and confers a high morbidity and mortality burden. Catheter ablation (CA) has emerged as the first line of therapy for the treatment of both persistent and paroxysmal AF.1-3 The 2023 American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society/American Heart Association (ACC/HRS/AHA) guidelines established CA even for patients who have not failed antiarrhythmic drug (AAD) therapy previously.4 Despite the improved efficacy of the procedure with novel technology over the years, AF recurrence rates post-index procedure are estimated to be between 20% and 40%, with the risk most pronounced in the first-year post-procedure.5,6 With emerging evidence suggesting that maintenance of sinus rhythm early in the disease course is predictive of future outcomes,7 there is a growing need to identify and risk-stratify patients for recurrence post-CA. Prior attempts to create risk stratification tools for AF recurrence post-CA are limited by sample size and limited post-procedure follow-up, and require the input of diagnostic or laboratory results.8-14 Currently, there are no available risk stratification tools that can be leveraged using readily available patient information without the need for imaging or laboratory results. Furthermore, an AF recurrence risk stratification tool could help clinicians identify modifiable risk factors that could be mitigated during the periprocedural period to improve the success of the intervention.

Using an extensive and robust patient-level database (ITHACA) with long-term follow-up, our objective is to identify baseline characteristics that are predictive of long-term recurrence that could be integrated into a risk stratification tool.

Methods

Population selection and follow-up

ITHACA is a single health system, multicenter registry of patients who underwent CA at 1 of 5 electrophysiology laboratories. The mean longitudinal follow-up is 42 months, and follow-up adherence is robust (approximately 97% for each variable collected). To minimize bias, trained clinicians manually extracted data from a standard electronic medical records system using a highly standardized protocol.

This study involved all patients from the Northwell Health system who underwent CA for AF between 2015 and 2021. Patients younger than 18 year with a previous left atrial (LA) ablation procedure were excluded from this cohort. Patients were followed longitudinally, with data collected on demographics, AF type (paroxysmal, persistent, or longstanding persistent), comorbidities, procedural details, and post-ablation outcomes (including recurrence, AAD use, repeat ablation, cardioversion, hospitalization, and adverse cardiovascular events). Data was collected at baseline, on the day of discharge post-procedure, at 3 months, at 12 months, at 24 months, and during the last patient visit.

The Northwell Health Institutional Review Board approved this study, and the research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Independent variables and baseline characteristics

The complete list of variables recorded in the database through manual chart review included age, sex, body mass index, race, type of AF, symptomatic AF, history of prior non-AF ablations, history of direct current cardioversion (DCCV), smoking history, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), heart failure (HF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypertension (HTN), hyperlipidemia (HLD), diabetes mellitus (DM), asthma, coronary artery disease (CAD) including a history of percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft, peripheral vascular disease (PVD), end-stage renal disease (ESRD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), thyroid disease, liver disease, cancer, valvular disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke. The implantation of pacemakers (PPM), cardiac defibrillators (ICD), and loop recorders (ILR) were also documented. Symptomatic AF was assessed using patient chart notes indicating symptoms associated with AF, such as palpitations, shortness of breath, lightheadedness, dizziness, near syncope, syncope, weakness, and fatigue. Baseline medications were also recorded, including beta blockers, AADs, oral anticoagulation, and calcium channel blockers.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was a composite outcome of AF recurrence, defined as documented AF recurrence, patient endorsement of AF symptoms, DCCV, redo ablation, and initiation of AADs post-ablation. The definition used for the primary outcome is aligned with primary effectiveness endpoints for CA success, as commonly seen in investigator device exemption (IDE) trials. Secondary outcomes included stroke and mortality. AF recurrence at 12 months, 24 months, and the last follow-up, which was 42 months on average, was identified using documentation (electrocardiogram, implantable cardiac monitor, wearable devices) or chart notes documenting symptoms consistent with prior AF episodes for each patient. All documented AF episodes were counted as recurrence regardless of duration and symptoms.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were summarized as mean ± SD if normally distributed and median ± IQR if not. Categorical data were presented as counts and percentages. The Student’s t-test, 1-way analysis of variance, χ2 test, and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare differences across groups. Continuous variables that were converted to binary were done using the median value. For the purposes of multivariable regression, COPD and asthma were combined. Outcome prediction analysis was performed at 1 year and for long-term follow-up using a backward stepwise selection logistic regression model, with a P-value of greater than 0.2 being the cutoff value for exclusion from the model. Results were visualized using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, and forest plots were generated to present the regression odds ratios (OR). Using the coefficients from the regression model for the primary composite endpoint, we generated the equation for the risk score. The risk score values were separated into quartiles, classifying patients into 4 groups: low risk, low-moderate risk, moderate risk, and high risk. Youden index was calculated for the optimal risk-score cutoff for predicting the composite endpoint. Because of the lack of an external validation cohort, a k-1 machine learning validation method was used. Our sample was randomly split at 80% for the training set and 20% for the testing set. The model, using the preselected variables from the logistic regression, was trained on the 80% of the dataset and tested on the remaining 20% to assess the generalizability of our findings. Analysis was performed using RStudio 2023.12.1+402 "Ocean Storm" (Posit PBC), STATA/IC16.1 (StataCorp LLC). and Prism Version 10.3.0 (GraphPad).

Results

Patient characteristics

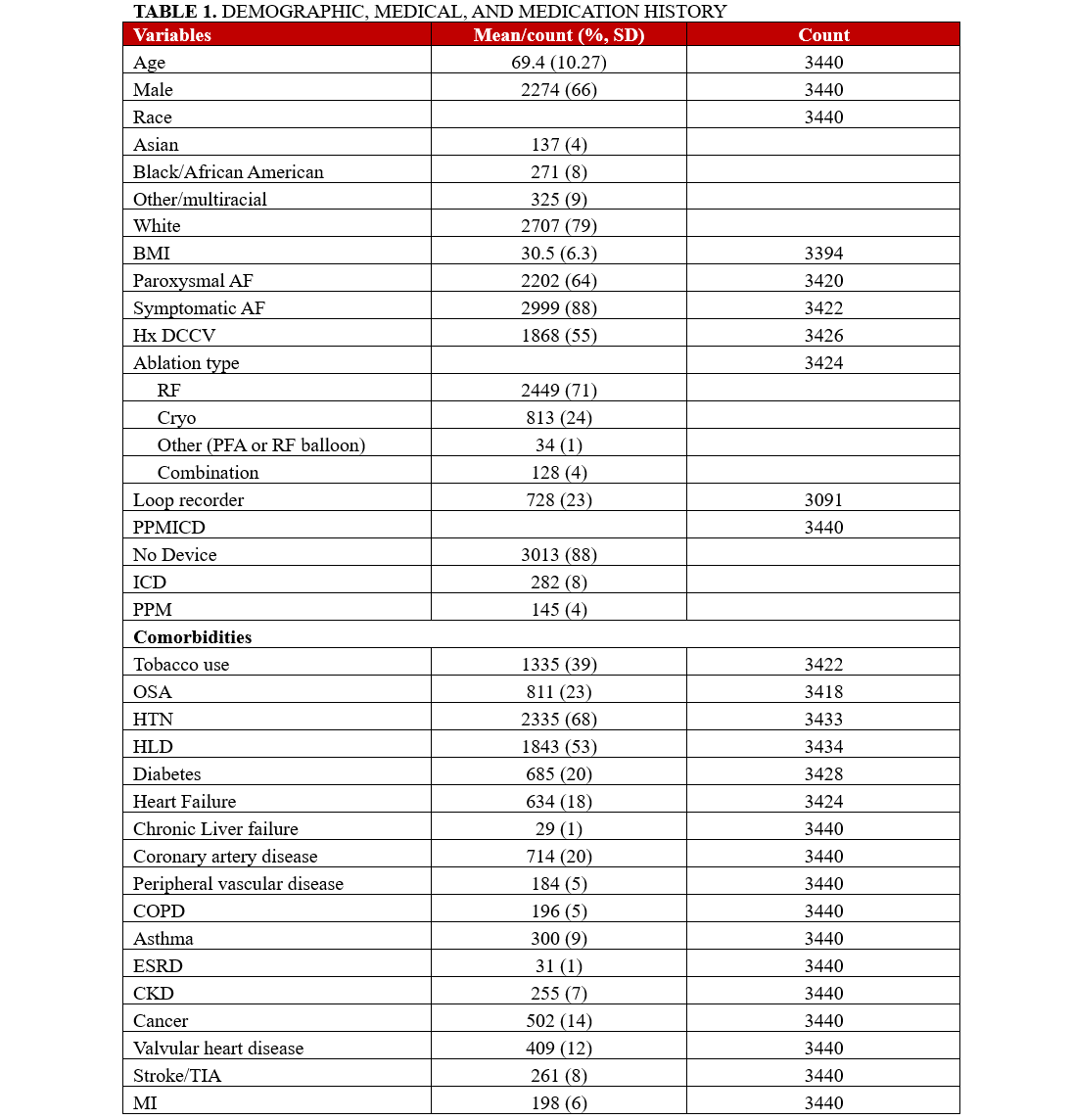

A total of 3440 patients were included in our analysis. The mean age of the participants was 69.4 ± 10.2 years, with the majority in the age range of 62 to 78 years. There was a total of 1166 women (44%) included in the cohort, 733 patients (21%) were non-White, and 2202 patients (64%) had paroxysmal AF. The most common comorbidities in our cohort included HTN (2335/3433 patients, 68%), HLD (1843/3434 patients, 53%), tobacco use (1335/3422 patients, 39%), OSA (811/3418 patients, 23%), DM (685/3428 patients, 20%), and CAD (714/3440 patients, 20%). A detailed summary of the baseline characteristics and outcomes are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Clinical outcomes

Singular AF recurrence

During the maximum follow-up of 42 months,1538 patients (44%) experienced AF recurrence as indicated by documentation or patient-endorsed AF symptoms during the study period. Of those patients, 846 (55%) experienced early AF recurrence, defined as AF recurrence during the blanking period of 3 months post-ablation, 339 (22%) presented with first-time AF recurrence from between 3 months and 12 months post-ablation, and 185 (12%) presented with first-time AF recurrence between 12 months and their last follow-up visit, which was 42 months on average.

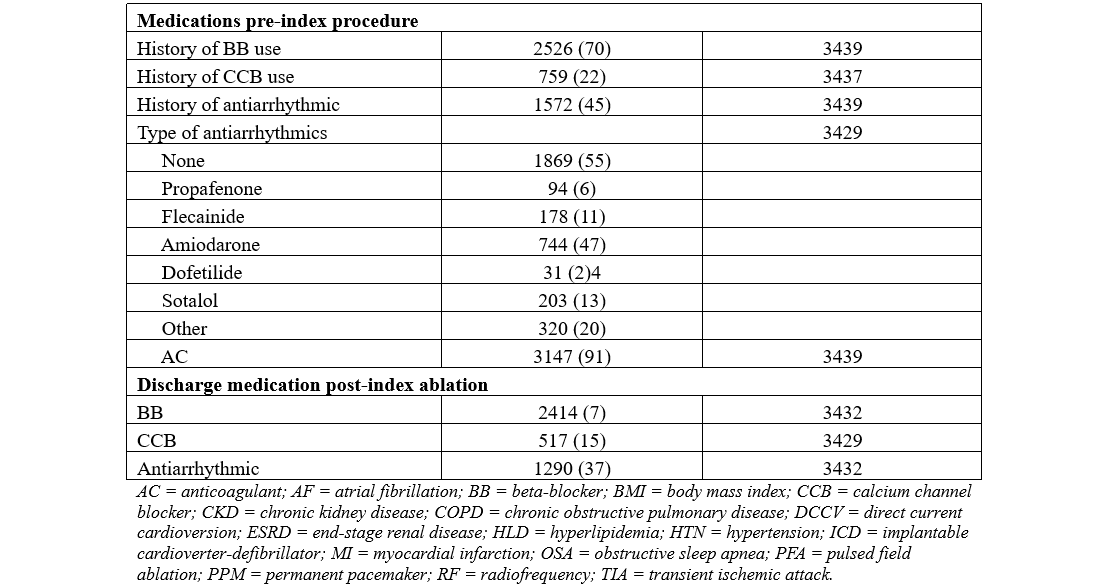

Composite outcome of AF recurrence

Overall, 1204 of our patients (35%) had the primary composite outcome at 12 months and 1651 patients (48%) experienced the composite outcome of AF recurrence at any point during the maximum follow-up period (mean: 42 months). One hundred-sixteen patients (3%) died during follow-up, and stroke occurred in 41 patients (1%).

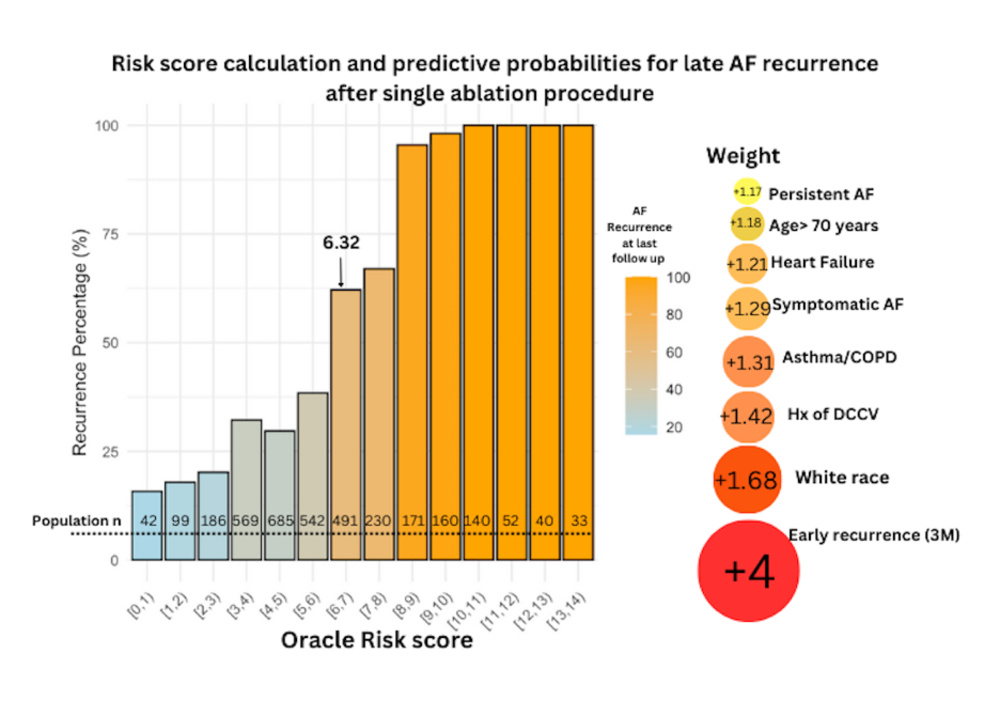

Logistic regression model for the composite outcome: 1-year and long-term follow-up

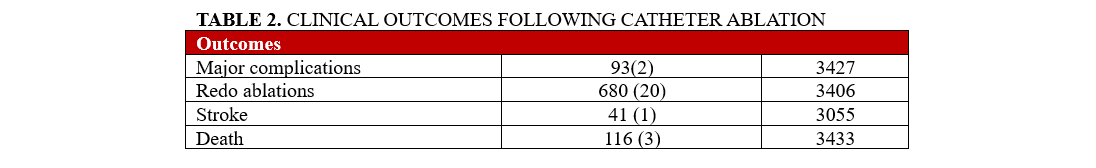

In a backward stepwise logistic regression for the primary composite outcome at 1 year post-ablation, age greater than 70 years (OR, 1.01, 1.00-1.02; P = .008) and persistent AF (OR, 1.33, 1.12-1.57; P = .001) were independently associated with the composite outcome. The prediction performance (area under the curve [AUC] = 0.56) of the 1-year model was suboptimal compared with the long-term outcome model. In a backward stepwise logistic regression for the primary outcome at 42 months, we identified 8 key variables, which were independently associated with our primary composite outcome. In detail, age greater than seventy years (OR, 1.18, 1.01-1.39; P = .05), White race (OR, 1.68, 1.06-2.67; P = .026), persistent AF (OR, 1.17, 1.01-1.37; P = .04), asthma/COPD (OR, 1.31, 1.01-1.68; P = .034), heart failure (OR, 1.21, 1.01-1.47; P = 0.05), history of DCCV (OR, 1.420944, 1.2-1.68; P = .001), symptomatic AF (OR, 1.29, 1-1.6; P = .044), and early recurrence (OR, 4, 3.4-4.8; P = .001) were associated with higher incidence of the composite endpoint (Figure 1). Sex, renal function, ablation type, and history of AAD use were not significant and were not associated with higher incidence of the composite outcome.

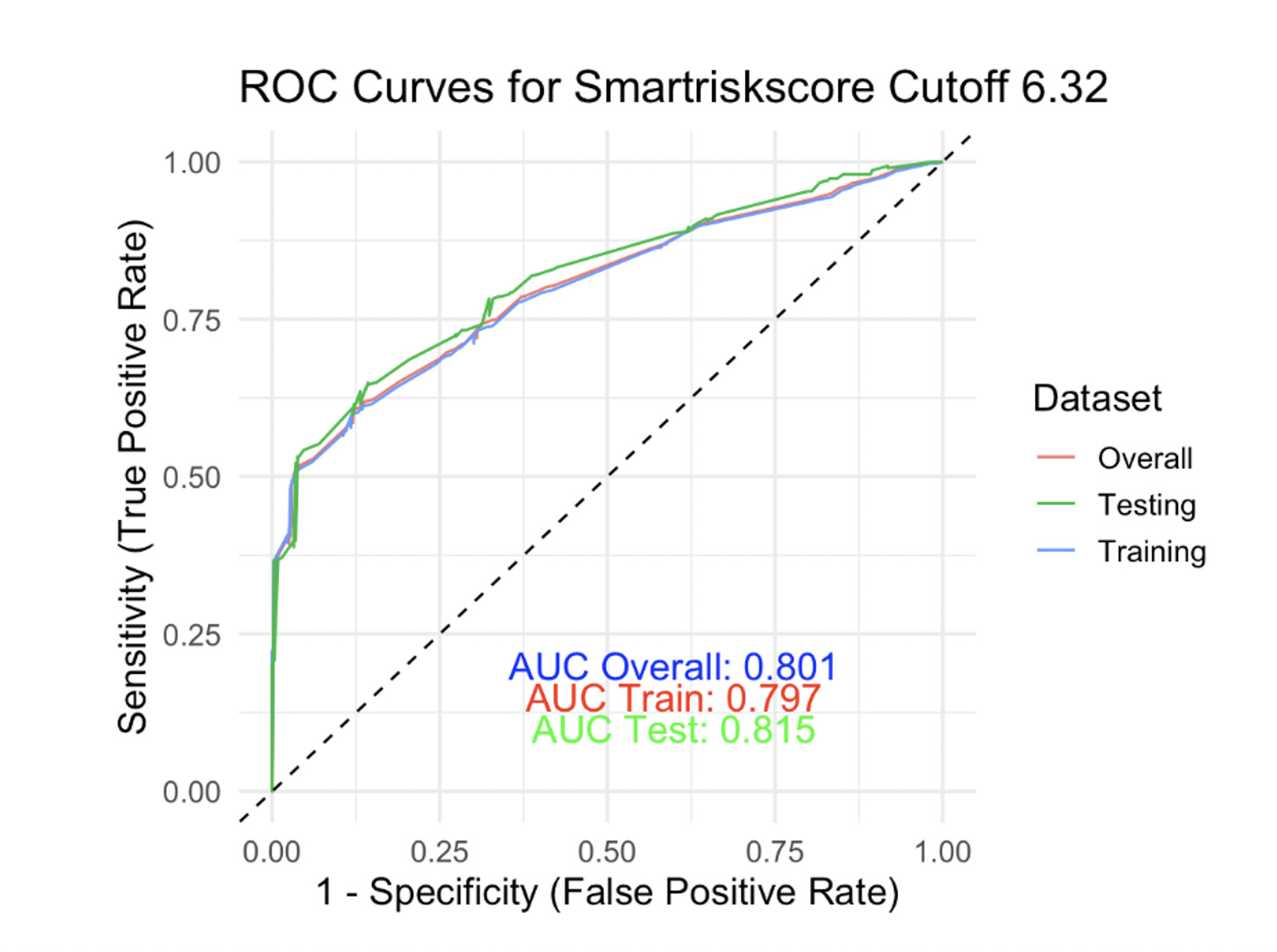

Cryoablation (OR, 1.18, 0.98-1.43) and ESRD (OR, 2, 0.85-5.11) were more frequent in patients who presented with the composite outcome, but did not reach statistical significance. An ROC curve was generated based on the above 8 predictors with an AUC equal to 0.71. Early AF recurrence within the blanking period of 3 months was the strongest predictor of the composite outcome in our model. Patients with AF recurrence during the blanking period were twice as likely to present with the composite outcome throughout the follow-up period compared with patients with no events during the blanking period.

Creating a risk score to predict composite outcome at 42 months

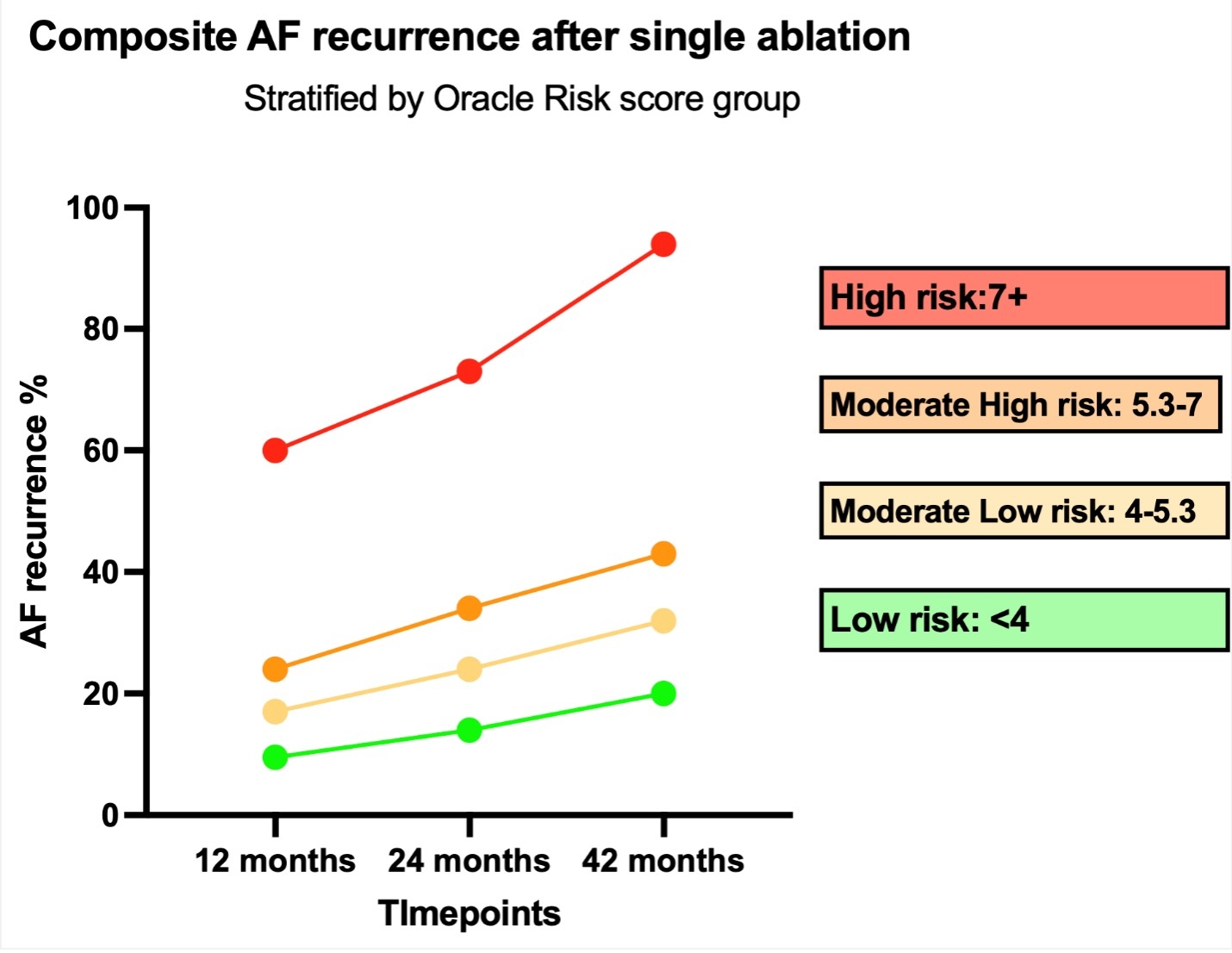

Only statistically significant variables from the multivariable logistic regression, including age greater than 70 years, White race, asthma/COPD, persistent AF, early recurrence, heart failure, history of DCCV, and symptomatic AF, were used to generate a prediction score. Sex, renal function, and type of ablation did not improve on the prognostic power of our risk tool and were not included. The regression coefficient of each variable was used as a multiplier to formulate the score equation. The score in our population ranged from 0 to 13.26, and the median was 5.3. The population was then stratified into quartiles based on risk scores: 0-4, 4-5.3, 5.3-7, and 7+. At the time of the last follow-up, the percentages of the composite outcome were 20%, 32%, 43%, and 94% for the low risk, low-moderate risk, moderate-high risk, and high-risk groups, respectively (P = .01). We found that the cumulative incidence of the composite outcome was higher in groups with higher risk score at every time point (12 months, 24 months, last follow-up).

We also noticed that the annual risk of the composite outcome was similar among the low, low-moderate, and moderate-high groups (mean: +5.4%), but it was higher for the high-risk group (mean: +14.2%), P = .03. Details regarding the composite outcome progression across groups are seen in Figures 2 and 3. Using the Youden index in order to select the optimal predicted probability score cut-off, we found that this was for a score value of 6.32, corresponding with a sensitivity (SENSE) of 78% and a specificity (SPEC) of 73%. To validate our model, we used the k-1 machine learning validation method running one thousand random splits (80/20) for training and testing the model respectively. The results, as displayed in Figure 4, indicate that the overall AUC was 0.80 and the AUC on the testing sample was 0.815 (SENSE = 79%; SPEC = 72%).

Discussion

Main findings

Based on a retrospective analysis of 3440 patients undergoing de novo CA for AF, our study found a composite outcome rate of 48% from the time of the index procedure until the last follow up visit (42 months). Predictors independently associated with the primary composite outcome were persistent AF, age greater than 70 years, heart failure, symptomatic AF, asthma/COPD, history of DCCV, White race, and early recurrence, in order of magnitude. Using the above variables, we developed a model to predict the long-term composite outcome inclusive of AF recurrence, DCCV, redo ablation, and initiation of AADs post-ablation with a maximum accuracy of 77%. Based on the predictive model, we developed a risk stratification tool to categorize patients into low-risk, low-moderate risk, high-moderate risk, and high risk for the composite outcome based on their periprocedural clinical phenotypes.

Previous risk prediction models

To date, multiple risk prediction tools have been created to predict AF recurrence following a CA. The BASE-AF2 score—which analyzes BMI, LA dilation, smoking history, early AF recurrence, duration of AF history, and AF type—was used in a 2013 study of 236 patients who underwent cryoablation to predict AF recurrence up to 30 months post-procedure; it resulted in a tool with an AUC of 0.93 for those with more than 3 such risk factors.12 In a subsequent study, the APPLE score had an AUC of 0.634 for the prediction of AF recurrence within 1 year following ablation among 1145 patients; this score includes all modalities of ablations and uses age, AF type, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), LA diameter, and left ventricular ejection fraction.8

The ATLAS, CAAP-AF, and MB-Later scores have predicted AF recurrence 3 to 4 years after ablation using AF type, LA measurements, and sex.9-11 Both ATLAS (n = 1934) and CAAP-AF (n = 2062) also included age, while additional considerations included smoking (ATLAS), CAD, failed AAD (CAAP-AF), early recurrence, and bundle branch block (MB-Later). The AUC for MB-Later (n = 133) was 0.782 and CAAP-AF obtained an AUC of 0.650, while ATLAS presented Kaplan-Meier survival curves without an AUC.

One of the most recent attempts, the HASBLP score, achieved an AUC of 0.77 when predicting AF recurrence 2 years post-procedure among 1065 patients. This score included age, BMI, AF type, snoring, length of AF history and LA size, but did not differentiate between persistent and paroxysmal patients.14 The LAGO (n = 243) score primarily used echocardiographic information, including type of AF, structural heart disease, CHA2DS2-VASC score, LA diameter, and LA sphericity, and followed patients for 3 years.13 A meta-analysis done comparing an additional 4 AF prediction models, including the 6 mentioned above, found that all but 1 tool had a significant predictive value, with AUC’s ranging from 0.553 to 0.669.15 The scores with the highest AUCs all included early AF recurrence as a risk factor for recurrence between 12 and 31 months post-ablation. Current risk prediction tools require the use of either laboratory data, such as eGFR, or echocardiographic data, such as LA measurement, and focus only on AF recurrence as the primary outcome for a maximum of 31 months post-ablation.

ORACLE-AF Model

The ORACLE-AF Model [symptOmatic AF, Race (White), AF Type (persistent), Cardioversion, Late Age > 70, Early AF recurrence, Asthma/COPD, Heart Failure] uses 8 independent variables that were associated with the composite outcome by 42 months post-de novo CA in our cohort. While all these variables have been reported to affect the efficacy of CA, the fact that White race and asthma/COPD are the second and fourth most impactful variable, respectively, in ORACLE-AF is surprising compared with the magnitude of importance traditional risk factors such as persistent AF, age greater than 70 years, and HF have in predicting the composite endpoint.16-27

While it is impossible to make direct comparisons to other tools because of the differing study population, the performance of ORACLE-AF (AUC = 0.80) was comparable to previously published models without the need of preprocedural imaging or lab data and distinctly focused on predicting long-term AF recurrence. The comparability between ORACLE-AF and previous models underscores the need to further refine and identify novel echo parameters outside of classic LA measurements, as previous models using LA measurements did not outperform our model. Further attempts to make a direct comparison between the performance of ORACLE-AF and other models with our cohort was unobtainable, as the ITHACA database does not contain the imaging or laboratory information that are requisites for other models to achieve accurate results.

Clinical implications

The variables used within our model can be categorized into those associated with either the chronicity or the comorbidities of AF. In line with traditional predictive models, persistent AF and history of DCCV are suggestive of patients with more progressive disease. Patients with persistent AF are more likely to receive DCCV while acutely symptomatic because of intolerance of atrioventricular dyssynchrony, loss of atrial kick, or inability to achieve adequate rate control. Patients who previously endorsed symptoms pre-ablation (nearly 90% of the cohort) are more likely to seek care for recurrent appreciable symptoms, which is a noted limitation of the analysis. Comorbidities associated with AF such as HF and pulmonary disease demonstrate the important of multidisciplinary management for chronic disease. COPD and asthma are associated with worse outcomes following CA, and adherence to continuous positive airway pressure for greater than 290 minutes per night is crucial for the maintenance of sinus rhythm post-CA.25,28 The bidirectional relationship between the dual cardiac epidemics of HF and AF are well reported, with the pathophysiological interplay of the disease often begetting one another; HF can increase LA pressure triggering the development of AF, while persistent AF can result in tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy.

Although not significant, and likely because of the low overall incidence rate in the cohort (1%), ESRD demonstrated a trend toward being associated with long-term AF recurrence. It is interesting to note that BMI was not associated with long-term AF recurrence within our cohort, a finding that is commonly reported in the existing literature.29,30 Like HF and AF, the relationship between obesity and AF is both bidirectional and multifactorial. That our cohort did not demonstrate this relationship speaks to the ever-evolving information surrounding the exact pathophysiological mechanisms occurring within AF. More studies are needed to elucidate this connection, especially considering the growing epidemiological disease burden imparted by both AF and obesity.

Non-modifiable risk factors, such as age, further support the importance of early CA in the AF disease process.31 When compared with White patients in our cohort, non-White patients had improved outcomes, concordant with the current literature that suggests minorities have better outcomes following CA. However, minorities are less likely to receive a CA despite the evidence suggesting that they would significantly benefit from the procedure.32,33 This finding underscores the importance of equitable access to tertiary care providers.

Early recurrence contributed the greatest weight to the ORACLE-AF risk score, a finding consistent with the reported literature, and common among the highest performing AF recurrence prediction models. However, though early recurrence within the blanking period has been well described as a predictor of 1-year recurrence post-CA, the present analysis found it was only significantly associated with long-term AF recurrence.34 This finding suggests the need to expand the evaluation period beyond 1 year to fully understand the pathophysiological mechanism of early recurrence that drives long-term recurrence. The inflammatory response leading to early recurrence could potentially indicate atrial remodeling and structural changes, resulting in long-term recurrence. It is important to note that, because of the inclusion of early AF recurrence in the ORACLE-AF model, only a preliminary risk profile can be created pre-ablation, with early recurrence status input after the blanking period to create a more comprehensive personalized risk profile for the patient.

The ORACLE-AF model provides insight into a patient’s individualized long-term risk profile for the composite outcome comprising AF recurrence, DCCV, redo ablation, and initiation of AADs post-ablation; it uses medical information that is easy to gather and does not require the input of echocardiographic or laboratory data. Chronicity and comorbidities are highlighted as key variables for the long-term maintenance of sinus rhythm post-CA, suggesting that early intervention and management of chronic disease are critical. By using ORACLE-AF, electrophysiologists can risk-stratify their patients to personalize AF management and thereby optimize long-term outcomes. Furthermore, the risk-prediction model suggests that patients who experience early recurrence may have a more aggressive substrate requiring close longitudinal follow-up and early reintervention; however, the mechanism of this association with long-term recurrence needs further investigation.

Limitations

ITHACA is a retrospective cohort and therefore has limitations that apply to all similar databases. Although we reviewed all available data, as is inherent to the limitations of all retrospective analysis, some of the variables used in the analysis had a maximum missingness of roughly 2%. As such, pertinent medical conditions, such as thyroid disease and pericardial disease, were unable to be collected because of expected variability within the medical records. Additionally, it is important to note that the ORACLE-AF model does not use echocardiographic variables. Some variables such as LA size can be surrogates for atrial cardiomyopathy, which has been demonstrated as an independent risk factor for recurrence.35,36 The lack of these variables may limit the overall accuracy of the ORACLE-AF model.

Another limitation of our study is that the precise timing of AF recurrence was unknown and was therefore approximately estimated by the timing of the nearest visit. Furthermore, detection of AF recurrence within the cohort was not uniform, creating possible statistical discrepancies in AF recurrence between those followed with continuous monitoring and those followed with traditional methods. This reflects the “real-world” data acquisition, as all ablation patients were included in the analysis, regardless of monitoring status.

Additionally, because of the timing of the creation of the database, only 1% of the patients had a PFA ablation performed. PFA has since become increasingly popular, as contemporary studies have demonstrated its comparable safety and efficacy to thermal ablations.37,38 Subsequent studies using the ITHACA database will include PFA patients to validate our model within this population. Creation of the database had a primary focus on AF ablations and did not consider other ablation procedures outside of pulmonary vein isolations. Our analysis and our prediction tool were not externally validated. However, the internal validation was performed using a machine learning approach to improve the overall validity of the model. Future studies will be performed to externally validate the ORACLE-AF model.

Conclusions

Using machine learning, we created a predictive tool to allow for individualized risk prediction for long-term AF recurrence following CA. The ORACLE-AF model can be used during the medical decision-making process between patient and provider to provide valuable insights regarding ablation outcomes. The variables found within the ORACLE-AF model highlight the need to consider risk factors not typically associated with long-term AF recurrence during pre-ablation consultation.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Jonas Leavitt, BS1,2; Dimitrios Varrias, MD1; Christopher Gasparis, MD1,2; Elliot Wolf, BA1; Stefanos Zafeiropoulos, MD1; Ari Zimmer, MD1; Laurence M. Epstein, MD1; Kristie M. Coleman, MPH, RN1; Stavros E. Mountantonakis, MD, MBA1

From the 1Northwell Cardiovascular Institute, Center for Arrhythmias, New Hyde Park, New York; 2Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, New York.

Disclosures: The authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Address for correspondence: Jonas Leavitt, BS, Lenox Hill Hospital, 100 East 77th Street, New York, NY 10075, USA. Email: jleavitt@northwell.edu

References

1. Hsu JC, Darden D, Du C, et al. Initial findings From the National Cardiovascular Data registry of atrial fibrillation ablation procedures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81(9):867-878. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.11.060

2. Cappato R, Calkins H, Chen SA, et al. Updated worldwide survey on the methods, efficacy, and safety of catheter ablation for human atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3(1):32-38. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.109.859116

3. Packer DL, Mark DB, Robb RA, et al; CABANA Investigators. Effect of catheter ablation vs antiarrhythmic drug therapy on mortality, stroke, bleeding, and cardiac arrest among patients with atrial fibrillation: the CABANA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(13):1261-1274. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.0693

4. Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, et al; Peer Review Committee Members. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149(1):e1-e156. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001193

5. Darby AE. Recurrent atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation: considerations for repeat ablation and strategies to optimize success. J Atr Fibrillation. 2016;9(1):1427. doi:10.4022/jafib.1427

6. Hussein AA, Saliba WI, Martin DO, et al. Natural history and long-term outcomes of ablated atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4(3):271-278. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.111.962100

7. Kirchhof P, Camm AJ, Goette A, et al; EAST-AFNET 4 Trial Investigators. Early rhythm-control therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1305-1316. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2019422

8. Kornej J, Hindricks G, Shoemaker MB, et al. The APPLE score: a novel and simple score for the prediction of rhythm outcomes after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Clin Res Cardiol. 2015;104(10):871-876. doi:10.1007/s00392-015-0856-x

9. Mesquita J, Ferreira AM, Cavaco D, et al. Development and validation of a risk score for predicting atrial fibrillation recurrence after a first catheter ablation procedure - ATLAS score. Europace. 2018;20(FI_3):f428-f435. doi: 10.1093/europace/eux265

10. Mujović N, Marinković M, Marković N, Shantsila A, Lip GY, Potpara TS. Prediction of very late arrhythmia recurrence after radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: the MB-LATER clinical score. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40828. doi:10.1038/srep40828

11. Winkle RA, Jarman JW, Mead RH, et al. Predicting atrial fibrillation ablation outcome: the CAAP-AF score. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13(11):2119-2125. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.07.018

12. Canpolat U, Aytemir K, Yorgun H, Şahiner L, Kaya EB, Oto A. A proposal for a new scoring system in the prediction of catheter ablation outcomes: promising results from the Turkish Cryoablation registry. Int J Cardiol. 2013;169(3):201-206. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.08.097

13. Bisbal F, Alarcón F, Ferrero-de-Loma-Osorio A, et al. Left atrial geometry and outcome of atrial fibrillation ablation: results from the multicentre LAGO-AF study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19(9):1002-1009. doi:10.1093/ehjci/jey060

14. Han W, Liu Y, Sha R, et al. A prediction model of atrial fibrillation recurrence after first catheter ablation by a nomogram: HASBLP score. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:934664. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.934664.

15. Mulder MJ, Kemme MJB, Hopman LHGA, et al. Comparison of the predictive value of ten risk scores for outcomes of atrial fibrillation patients undergoing radiofrequency pulmonary vein isolation. Int J Cardiol. 2021;344:103-110. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.09.029

16. Kim YG, Boo KY, Choi JI, et al. Early recurrence is reliable predictor of late recurrence after radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2021;7(3):343-351. doi:10.1016/j.jacep.2020.09.029

17. Willems S, Khairy P, Andrade JG, et al; ADVICE Trial Investigators. Redefining the blanking period after catheter ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: insights from the ADVICE (Adenosine Following Pulmonary Vein Isolation to Target Dormant Conduction Elimination) trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016;9(8):e003909. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.115.003909

18. Boriani G, Bonini N, Vitolo M, et al. Asymptomatic vs. symptomatic atrial fibrillation: clinical outcomes in heart failure patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2024;119:53-63. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2023.09.009

19. Bukari A, Nayak H, Aziz Z, Deshmukh A, Tung R, Ozcan C. Impact of race and gender on clinical outcomes of catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2017;40(10):1073-1079. doi:10.1111/pace.13165

20. Yu HT, Kim IS, Kim TH, et al. Persistent atrial fibrillation over 3 years is associated with higher recurrence after catheter ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2020;31(2):457-464. doi:10.1111/jce.14345

21. Wasmer K, Eckardt L, Breithardt G. Predisposing factors for atrial fibrillation in the elderly. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14(3):179-184. doi:10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2017.03.010

22. Biffi M, Boriani G, Bartolotti M, Bacchi Reggiani L, Zannoli R, Branzi A. Atrial fibrillation recurrence after internal cardioversion: prognostic importance of electrophysiological parameters. Heart. 2002;87(5):443-448. doi:10.1136/heart.87.5.443

23. Pandit SV, Jalife J. Aging and atrial fibrillation research: where we are and where we should go. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4(2):186-187. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.11.011

24. Bahnson TD, Giczewska A, Mark DB, et al; CABANA Investigators. Association between age and outcomes of catheter ablation versus medical therapy for atrial fibrillation: results from the CABANA trial. Circulation. 2022;145(11):796-804. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.055297

25. Skoll D, Lu R, Gasmelseed AY, et al. Asthma is associated with higher recurrence rates of atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2025;22(11):2810-2818. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.12.011

26. Cha YM, Wokhlu A, Asirvatham SJ, et al. Success of ablation for atrial fibrillation in isolated left ventricular diastolic dysfunction: a comparison to systolic dysfunction and normal ventricular function. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4(5):724-732. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.110.960690

27. Wilton SB, Fundytus A, Ghali WA, et al. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness and safety of catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in patients with versus without left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(9):1284-1291. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.06.053

28. Varrias D, Kossack A, Leavitt J, et al. Adherence to CPAP for patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing catheter ablation: a "real-world" analysis. Heart Rhythm. 2025:S1547-5271(25)00382-0. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2025.03.163

29. Sivasambu B, Balouch MA, Zghaib T, et al. Increased rates of atrial fibrillation recurrence following pulmonary vein isolation in overweight and obese patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2018;29(2):239-245. doi:10.1111/jce.13388

30. Vermeer J, Houterman S, Medendorp N, van der Voort P, Dekker L; Ablation Registration Committee of the Netherlands Heart Registration. Body mass index and pulmonary vein isolation: real-world data on outcomes and quality of life. Europace. 2024;26(6):euae157. doi:10.1093/europace/euae157

31. Andrade JG, Wells GA, Deyell MW, et al; EARLY-AF Investigators. Cryoablation or drug therapy for initial treatment of atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(4):305-315. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2029980

32. Vandenberk B, Chew DS, Parkash R, Gillis AM. Sex and racial disparities in catheter ablation. Heart Rhythm O2. 2022;3(6Part B):771-782. doi:10.1016/j.hroo.2022.08.002

33. Eberly LA, Garg L, Yang L, et al. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in management of incident paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e210247. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.024

34. Vaishnav AS, Levine E, Coleman KM, et al. Early recurrence of atrial fibrillation after pulmonary vein isolation: a comparative analysis between cryogenic and contact force radiofrequency ablation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2020;57(1):67-75. doi:10.1007/s10840-019-00639-3

35. Goette A, Corradi D, Dobrev D, et al. Atrial cardiomyopathy revisited-evolution of a concept: a clinical consensus statement of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC, the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asian Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS). Europace. 2024;26(9):euae204. doi:10.1093/europace/euae204

36. Chollet L, Iqbal SUR, Wittmer S, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation phenotype and left atrial volume on outcome after pulmonary vein isolation. Europace. 2024;26(4):euae071. doi:10.1093/europace/euae071

37. Chun KJ, Miklavčič D, Vlachos K, et al. State-of-the-art pulsed field ablation for cardiac arrhythmias: ongoing evolution and future perspective. Europace. 2024;26(6):euae134. doi:10.1093/europace/euae134

38. Ekanem E, Neuzil P, Reichlin T, et al. Safety of pulsed field ablation in more than 17,000 patients with atrial fibrillation in the MANIFEST-17K study. Nat Med. 2024;30(7):2020-2029. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03114-3