Shortened Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Duration After Percutaneous Patent Foramen Ovale and Atrial Septal Defect Closure

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

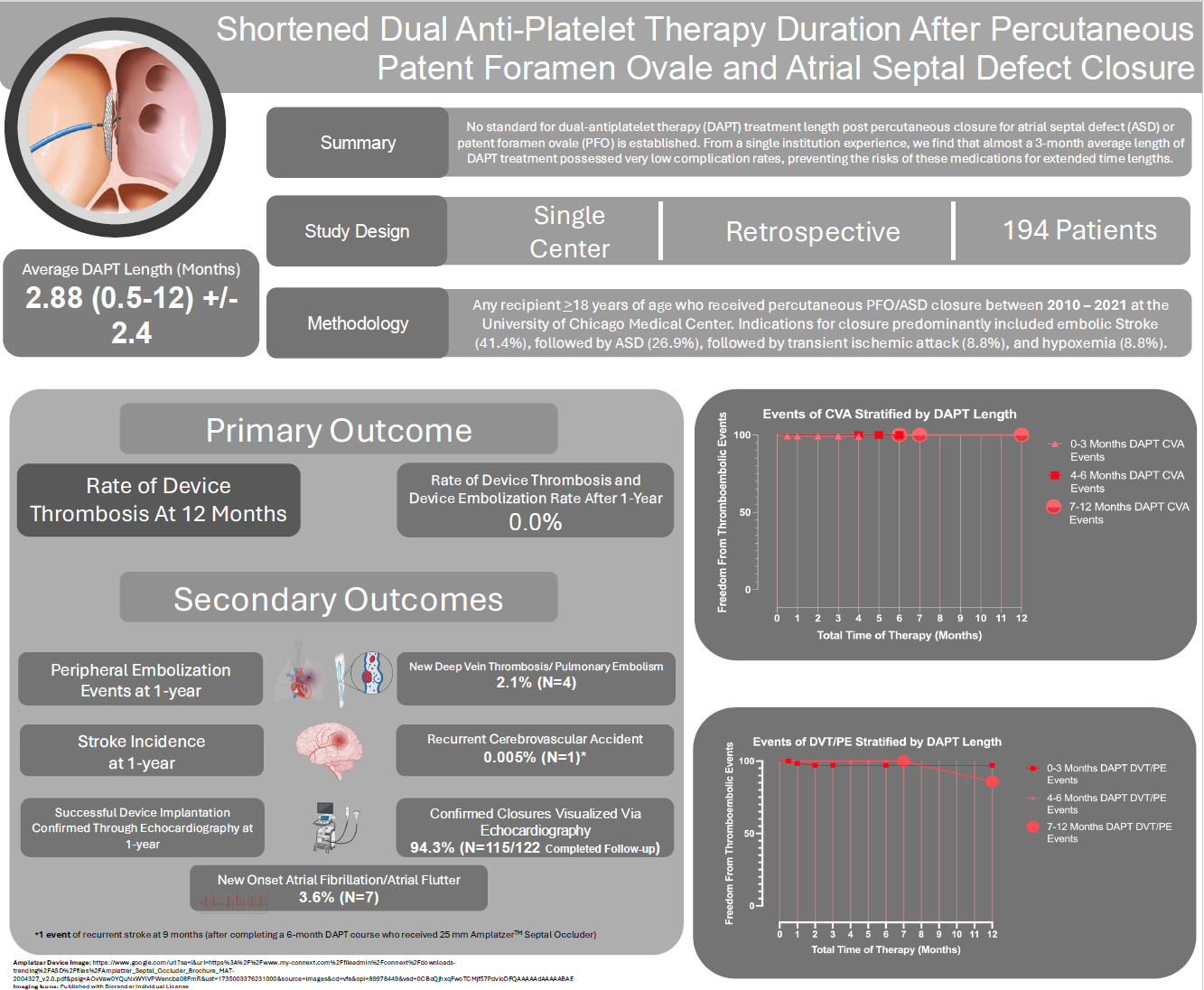

Objectives. Current guidelines recommend patent foramen ovale (PFO) closure in patients with cryptogenic stroke, while atrial septal defect (ASD) closure is indicated for a shunt with right atrial/right ventricular (RV) enlargement. Major procedural complication rates from PFO/ASD closure are low. However, there is a theoretical risk of thrombus formation early after implantation, prior to endothelialization of the device, that may be prevented by dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT). There is little data on the optimal timing and duration of DAPT post-device placement; thus, this study aimed to evaluate the safety of shortened DAPT after PFO/ASD closure with respect to device thrombosis and clinical stroke.

Methods. One hundred ninety-four patients 18 years or older who underwent transcatheter PFO/ASD closure from 2010 to 2021 were included in the study. The primary outcome was the rate of device thrombosis at 1 year. The secondary outcome was stroke and peripheral embolization at 1 year.

Results. Closures were primarily performed for cryptogenic stroke (41.9%) and ASD closure for RV enlargement (26.9%). The average length of DAPT was 2.91 ± 2.6 months. At 1 year, there were no cases of device thrombosis or embolization.

Conclusions. This study suggests that 3 months or less of DAPT may be safe in patients after percutaneous PFO/ASD closure.

Introduction

The prevalence of patent foramen ovale (PFO) has been reported to be up to 25% in the general population.1 Atrial septal defects (ASDs) are the second most common congenital defect, with the most significant proportion being secundum ASDs.2 Percutaneous transcatheter closure of secundum ASDs remains the standard of care in select patients with right ventricular (RV) overload and/or dysfunction.2 Until recently, the closure of PFOs in cryptogenic stroke was controversial. Furlan et al found that in patients with a PFO and cryptogenic stroke, PFO closure was not associated with improved outcomes over medical therapy.3 In 2017, the CLOSE and REDUCE trials showed a definitive reduction of stroke incidence in those who underwent PFO closure after a cryptogenic stroke compared with medical therapy.4,5 The 6-year outcome data from the RESPECT trial also demonstrated a reduction in ischemic stroke in those assigned to the PFO closure group.6 Based on these recent trials, 2020 guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and 2021 guidelines from the American Heart Association (AHA)/American Stroke Association newly recommended PFO closure in select patients with cryptogenic stroke for secondary prevention after careful exclusion of other potential sources of embolism.7,8

Overall, the major procedural complication rate from PFO closure is exceedingly low, especially in newer-generation devices.9 In a meta-analysis of 10 studies, significant complications of PFO closure, such as pericardial tamponade, device fracture, and myocardial infarction, were found to be 1.5%.10 Thrombus formation, while only observed in 1% to 2% of patients, is a recognizable and potentially harmful complication that may lead to stroke.11 Activation of the coagulation cascade and endothelialization of these devices is part of the natural healing processes, which contributes to eliminating any residual shunt.12 However, excessive coagulation may lead to dangerous thrombus formation on these closure devices. This occurrence is highest within the first month after implantation, but is rare after 1 year.13 However, there is a paucity of data regarding the optimal timing, type, and duration of antiplatelet or anticoagulation post-device placement.

To date, no randomized data is available regarding the optimal duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) following PFO/ASD closure. All recommendations are based on expert opinion, and 6 months of DAPT is recommended.7 This study aimed to evaluate the safety of a shortened DAPT course after PFO/ASD closure with respect to device thrombosis and clinical stroke.

Methods

This single-center retrospective study evaluated the use of a shortened duration of DAPT among patients with PFO/ASD closure. The Human Research and Ethics Committee at the University of Chicago approved this study. All patients provided written informed consent for the procedure, and their data was collected in a secure electronic database.

A total of 194 patients aged 18 years or older who had PFO or ASD closure from 2010 to 2021 at our institution were included. PFO closure was pursued for patients with cryptogenic stroke or peripheral embolism. Cryptogenic stroke was diagnosed after screening, which included brain magnetic resonance imaging and/or computed tomography, at least 24-hour Holter monitoring, transthoracic echocardiography, and carotid Doppler. The American Academy of Neurology defined transient ischemic attack (TIA) as “brief episodes of neurological dysfunction resulting from focal cerebral ischemia not associated with permanent cerebral infarction.”14

PFO closure was also pursued preoperatively for patients undergoing liver transplantation or any surgery where a theoretical risk of paradoxical embolism was elevated. The diagnosis of PFO or ASD was made via either a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) or a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE). PFO was found with agitated saline injection, demonstrating a right-to-left shunt with or without the Valsalva maneuver. ASD was interpreted based on the Doppler flow elicited at the point of the interatrial septum. Additionally, ASD closure was pursued in patients with isolated secundum ASD with impaired functional capacity and/or right atrial (RA)/RV enlargement.

Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, breastfeeding, or unable to tolerate any duration of DAPT, or had another indication for long-term DAPT (such as percutaneous coronary intervention), active bacteremia/endocarditis, known intracardiac thrombi, or a life expectancy of less than 12 months.

Device selection was left to the implanting operator. The devices included the Amplatzer PFO Occluder (Abbott), Amplatzer ASD Occluder (Abbott), Amplatzer Cribriform Occluder (Abbott), and GORE CARDIOFORM Septal or ASD Occluder (W. L. Gore & Associates). The Amplatzer occluder devices have 2 self-expanding discs of a wire mesh of nickel-titanium (nitinol), which contains a polyester framework that aids in the endothelization process. These discs are connected via a thin waist that spans the distance of the tunnel or defect. The GORE CARDIOFORM Septal and ASD Occluders comprise 2 platinum-filled nitinol discs covered by polytetrafluoroethylene material, designed to be thromboresistant. This device also has a thin waist between both discs. Patients with a nickel allergy received a GORE CARDIOFORM Septal or ASD Occluder.

Baseline TTE or TEE was performed on all patients with an agitated saline study before intervention. The procedure was performed predominantly under moderate sedation with midazolam and fentanyl. General anesthesia was used for cases with hemodynamic instability, respiratory failure, or where the use of TEE was necessary. Bilateral femoral venous access was obtained in nearly all cases for device deployment and ViewFlex intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) (Abbott). Patients were given intravenous heparin (50-70 U/kg) to achieve an activated clotting time of 250 to 300 seconds throughout the case. Technical aspects of crossing the atrial defect were left to the discretion of the implanting physician. PFOs were sized using a bicaval view, and ASDs were sized using a sizing balloon and the stop-flow technique. ICE was used to ensure the left atrial disc was free of adjacent structures in the mid-left atrium. Fluoroscopy was used to confirm proper device positioning, and color Doppler via ICE was used to assess for any residual leak around the device.

Patients were kept overnight to monitor for bleeding complications, arrhythmias, and changes in neurologic status. TTE was obtained within 24 hours post-procedure. DAPT loading doses of aspirin (325 mg) and clopidogrel (600 mg) were given orally in the procedure room, then maintenance doses of aspirin (81 mg daily) and clopidogrel (75 mg daily) were given the days following the loading doses. As part of institutional practice, no other antiplatelet agent was given to the cohort. The duration of therapy was up to the provider—typically between 2 weeks and 12 months—but was encouraged to be as short as possible, based on patient characteristics such as age and previous cerebrovascular accident (CVA) history

Patients were seen in the clinic at 1, 6, and 12 months by the provider who performed the PFO/ASD closure. A complete history and physical were obtained, and each patient was evaluated for TIA/stroke, new atrial arrhythmias, bleeding complications, any cardiovascular complications, and new pulmonary embolism (PE)/deep vein thrombosis (DVT). TTE was obtained at 6 months and at 12 months. A neurologist evaluated any new TIA/stroke. Bleeding events were defined by Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria.15 Our primary outcome was the rate of device thrombosis at 12 months as measured by clinical history, defined by thrombotic/embolic events, including CVA/TIA, or systemic embolism incidence. Secondary outcomes were peripheral embolization at 12 months and successful device implantation as confirmed by follow-up echocardiography.

Continuous variables were presented as median and range. Paired t-test analysis was used to compare the pre- and post-intervention means. Statistical analysis was performed with Minitab 19 (Minitab, LLC).

Results

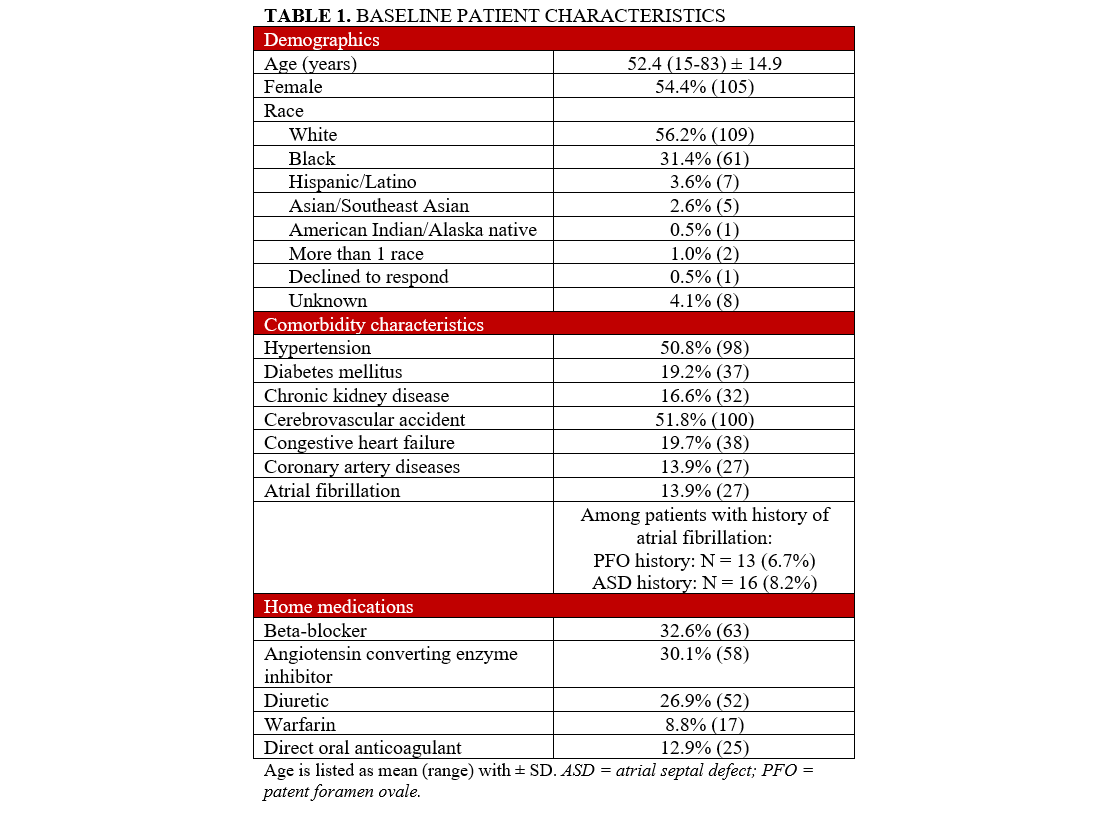

The baseline characteristics of the population are noted in Table 1. The mean age of the cohort was 52.4 ± 14.9 years; 105 (54.4%) patients were female. More than half (100, 51.8%) of the cohort had a history of CVA, while 27 (13.9%) had a history of atrial fibrillation (AF). Seventeen (8.8%) patients were on warfarin, and 25 (12.9%) were on a direct oral anticoagulant for treatment of PE/DVT or AF. No patients were on combined DAPT before the insertion of the device. One hundred-nine (56.2%) patients were Caucasian, 61 (31.4%) patients were Black, and 8 (4.1%) patients reported an unknown race or did not self-identify.

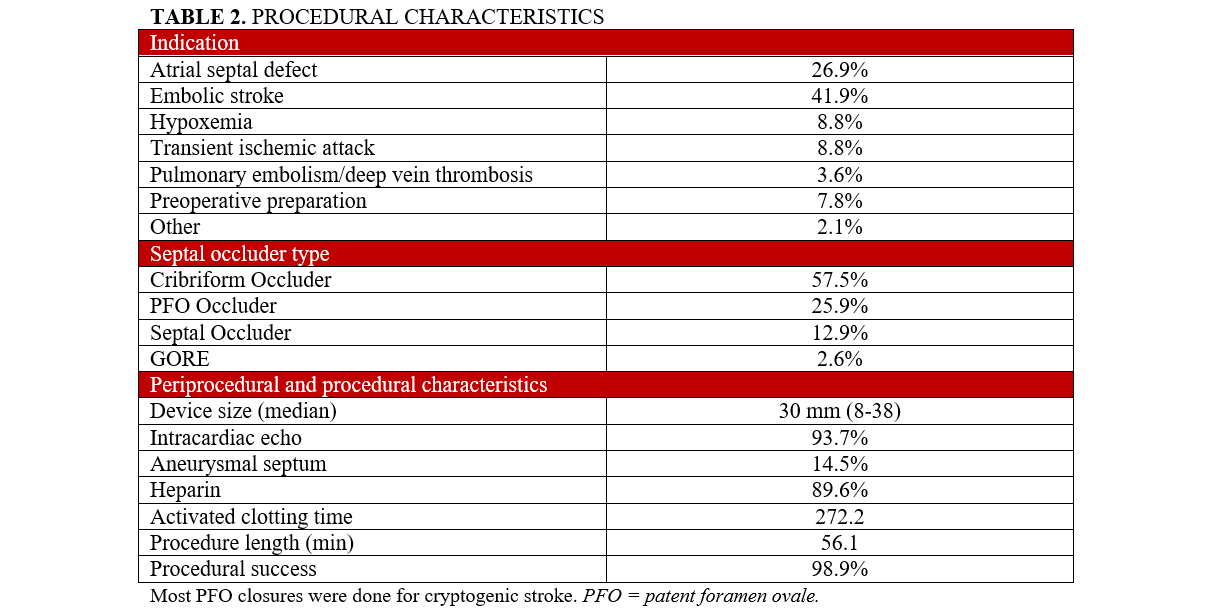

Procedural characteristics are described in Table 2. Most closures were performed because of a history of cryptogenic stroke (81, 41.9%) followed by ASD closure for RV enlargement (52, 26.9%). Preoperative closure (15, 7.8%) was primarily pursued in patients undergoing liver transplantation. The Amplatzer devices were used more than the Gore device (189 [97.4%] vs 5 [2.6%], respectively). The predominant Amplatzer occluder was the Cribriform Occluder, followed by the PFO and Septal Occluders (Table 2). ICE was performed in 182 (93.7%) cases, and aneurysmal septum was found in 28 (14.5%) patients. Procedural success, defined as the deployment of a closure device with a negative bubble study on ICE or TEE, occurred in 192 (98.9%) cases.

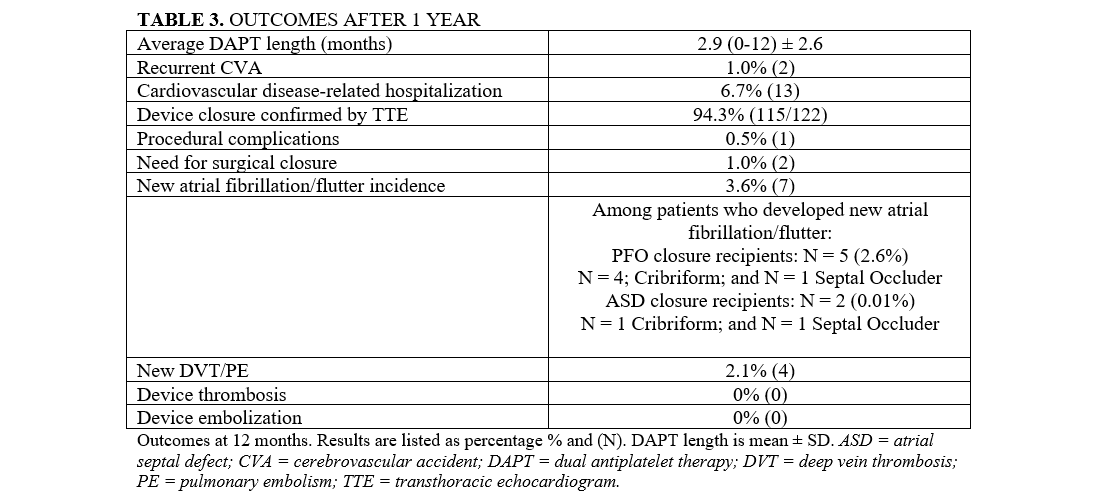

Table 3 describes outcomes measured at 1 year. The average length of DAPT was 2.91 months (0-12) ± 2.6 months. Fifty-seven (29%) patients received DAPT for 1 month, while 56 (29%) received DAPT for 3 months. After the completion of DAPT for each respective regimen, all patients continued aspirin 81 mg monotherapy. At 1 year, there were no cases of device thrombosis or device embolization. On sonographic evaluation, TTE showed successful device closure with no residual shunt at 12 months in 115 (94.3%) of the 122 recipients who had a 1-year follow-up. One (0.5%) patient had a significant femoral bleed requiring a blood transfusion, while 1 patient (0.5%) required surgical extraction and closure due to an undiagnosed nickel allergy. Another patient (0.5%) underwent robotic closure of a persistent shunt for the past 12 months. One (0.5%) patient had a recurrent stroke 9 months after closure with a 25-mm Amplatzer Septal Occluder, after completing 6 months of DAPT; this patient had a history of AF pre-device closure. Six (3.1%) patients were hospitalized because of cardiovascular issues such as supraventricular tachycardia, new left ventricular dysfunction, and the aforementioned cases. New-onset AF was seen in 7 (3.6%) patients: 5 (2.6%) and 2 (0.01%) in the PFO- and ASD-closure recipient groups, respectively. New DVT/PE was seen in 4 (2.1%) patients, all of whom were implanted with Amplatzer devices.

The estimated event-free survival stratified across CVA incidents and DVT/PE events is reported in the Central Figure. Among all stratified time lengths of DAPT (0-3 months, 4-6 months, and 7-12 months), there were no CVA events. There were 2 DVT/PE events within the 0- to 3-month DAPT group: 1 at 1 month and 1 at 2 months.

Discussion

In patients who underwent PFO closure for cryptogenic stroke or TIA, there were no cases of device thrombosis or device embolization at 12 months, with an average duration of DAPT for just under 3 months; 41.4% of patients had 2 months or less of antiplatelet therapy. There was 1 stroke post-closure that occurred after 6 months of DAPT. While there were no prospective trials evaluating reduced DAPT time lengths at the time of this study, 2 retrospective outcomes studies have demonstrated that a shortened DAPT strategy after PFO closure is just as safe as more extended strategies. Kefer et al performed procedures specifically for cryptogenic stroke, while our cohort reports outcomes over a more heterogeneous set of indications.16 The report by Guedeney et al from the AIR-FORCE cohort of 933 percutaneous PFO-closure recipients—96.9% of whom received DAPT for 3 months or less—potentially suggests that no temporary DAPT is a viable option; however, device distribution and follow-up frequency were sparsely reported.17 Yet, our findings demonstrate similar safety endpoints over similarly reduced DAPT prescription intervals.

The current literature does not have an agreed-upon duration for DAPT after PFO closure. Current AHA/American College of Cardiology guidelines offer no consensus and only cite expert opinion.2 Polzin et al demonstrated that, despite high on-treatment platelet reactivity among clopidogrel patients after PFO/ASD closure, no device thrombosis was detected among 140 patients;18 this suggests that combination therapy may not be warranted at all. The most recent trials utilized variable combinations and durations of therapy with up to 6 months of both aspirin and clopidogrel.4-6 In the RESPECT trial, 6% of patients received no therapy at all after closure.6 In the REDUCE trial, DAPT was specified for at least 3 days. After that, antiplatelet therapy was at the discretion of each participating site, consisting of any combination or monotherapy of aspirin, clopidogrel, or dipyridamole.5

Our data showed no evidence of device-related thrombosis or embolism at 1 year. Many patients (29.0%) received around 3 months of DAPT, while most others received DAPT for less than 1 month (41.4%). In particular, patients who were undergoing liver transplantation (7.8%) only received DAPT for 2 weeks because of their high bleeding risk; no device thrombosis in this group was observed. DAPT duration was shortened at the primary physician's discretion by assessing the individual’s clinical bleeding risks. It has been well documented that there are differences in device-related thrombosis across a spectrum of occluder devices; for example, in a 1000-patient study by Krumsdorf et al, GORE devices had a higher incidence of device-related thrombosis at the 6-month monitoring mark than Amplatzer devices (0.8% vs 0.0%).19 While our study was unable to control for these factors because device use was at the direction of the operator through a retrospective study model, we have found that Amplatzer devices at 1 year have comparable rates to those reported by Krumsdorf et al, indicating a continued signal of safety. Furthermore, the heterogeneity in device usage is attributed to the 2016 approval of the PFO occluder device, 6 years from the 2010 start of the study cohort.

Our patient cohort had similar rates of AF, DVT, and PE to what is found in the current literature. In the 2017 RESPECT trial, 3 (0.6%) patients who underwent PFO closure developed AF/atrial flutter; whereas, in the CLOSE trial, 4.6% of patients developed AF/atrial flutter, which is similar to our cohort (3.6%).4,6 We also found that both preprocedural ASD patients and postprocedural recipients of ASD closure comprised the majority of AF incidence and new-onset AF at 1-year follow-up, respectively—all of these patients received the Amplatzer Cribriform device. This contrasts with prior studies demonstrating GORE devices having a higher preponderance to developing postprocedural AF; notably, our cohort had a minority of GORE recipients, but this potentially indicates that the introduction of the Amplatzer Cribriform device may be a precipitant.20 Similarly, Saver et al found only 3 (0.6%) patients who developed new DVT/PE, compared with 4 (2.1%) patients in our cohort who developed new DVT/PE after PFO closure.6 Given that the Amplatzer device has relatively few complications with low risk for thrombosis, our data suggests that shorter durations of DAPT would be safe in these device recipients. However, because of the lower proportion of GORE devices in our study, generalizability in these recipients may be limited.

In our cohort, 1 patient had a large femoral bleed requiring blood transfusion (BARC Class 3a). In the CLOSE trial, 2 of 238 patients had a major or fatal bleeding event, while 3 of 400 patients had vascular events in the RESPECT trial.4,6 One patient in our cohort required surgical closure because of a nickel allergy, whereas 2 of 400 patients in the RESPECT trial required surgical closure for a persistent shunt.6 Overall, our study had similar device-related complications to those reported in the current literature.

Limitations

There are certain limitations to this study. First, the study only follows patients for 12 months. Also, the patient cohort may be too small to detect a difference in an otherwise well-tolerated, relatively safe procedure. Additionally, this study is a retrospective analysis performed at a single academic medical center. The duration of DAPT device selection and AF monitoring were left to the discretion of the implanter. The unique characteristics of each device may be a protective or contributing factor to complications and would need to be controlled in subsequent studies. In addition, most of the cases in this study were PFO closure, which may explain why the majority of the patients received PFO occluders/Cribriform devices instead of septal occluders. Furthermore, more patients in our study received an Amplatzer device than a GORE device, which may limit the generalizability of the safety of DAPT among GORE devices. The most common modality used to assess device endothelialization was noninvasive sonographic evaluation, which was used for this study and may be limited in visibility and reproducibility; novel imaging techniques that improve characterization of endothelialization should be implemented when performing further work on this topic. Future studies must directly compare durations of DAPT after PFO closure in a prospective fashion, specifically clarifying indications and controlling for a spectrum of device applications as a part of an effective comparison. In addition to ambiguity in DAPT length, it is unclear what role P2Y12 inhibitors vs aspirin monotherapy have post-closure. While there was minimal new arrhythmogenesis in our cohort in either PFO or ASD closure recipients, this incidence suggests that those underlying rhythm disorders may need to be further studied before generalizing these findings to this population. Future studies should also examine the utility of DAPT in patients who are already on therapeutic anticoagulation for indications such as AF or thromboembolism. These findings, particularly compared with randomized controlled findings, would be necessary before considering generalizability.

Conclusions

This single-center retrospective study suggests that 3 months or less of DAPT may be safe in patients after percutaneous PFO or ASD closure. A single antiplatelet regimen may also have similar preventative benefits. At 12 months, no cases of clinically relevant thromboembolic events attributed to device implantation were observed.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Ankur Srivastava, MD1; Dhruvil A. Patel, MD2; AbdulRahman Dia, MD3; Sandeep Nathan, MD, MS4; John E. Blair, MD5; Jonathan Paul, MD4; Prateek Sharma, MD4; Jennifer Smazil, APN4; Lauren Roark, RN4; Janet Friant, APN4; Moira McDowell, APN4; Rohan Kalathiya, MD6; Atman P. Shah, MD4

From the 1Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York; 2Department of Medicine, Section of Internal Medicine, University of Chicago Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois; 3Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Duly Health and Care, New Lenox, Illinois; 4Department of Medicine, Section of Cardiology, University of Chicago Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois; 5Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Cardiology, University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, Washington; 6Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Section of Cardiology, Johns Hopkins Medical Center, Baltimore, Maryland.

This project was submitted as an abstract and presented at the Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) 2022 annual conference held May 19 to 22, 2022 in Atlanta, Georgia; and at the Cardiovascular Research Therapeutics (CRT) 2024 annual conference held March 9 to 12, 2024 in Washington, DC.

Disclosures: Dr Shah is a consultant and proctor for Abbott Vascular. Dr Patel is a consultant for SumHealth. The remaining authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Address for correspondence: Dhruvil A. Patel, MD, 5841 S Maryland Ave, MC6080, Chicago, IL 60637, USA. Email: Dhruvil.patel@uchicagomedicine.org; X: @dhrupat97, @SandeepNathanMD, @Jonathan_PaulMD, @RohanKalMD

References

1. Hagen PT, Scholz DG, Edwards WD. Incidence and size of patent foramen ovale during the first 10 decades of life: an autopsy study of 965 normal hearts. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59(1):17-20. doi:10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60336-x

2. Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139(14):e698-e800. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000603

3. Furlan AJ, Reisman M, Massaro J, et al; CLOSURE I Investigators. Closure or medical therapy for cryptogenic stroke with patent foramen ovale. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):991-9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1009639

4. Mas JL, Derumeaux G, Guillon B, et al; CLOSE Investigators. Patent foramen ovale closure or anticoagulation vs. antiplatelets after stroke. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(11):1011-1021. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1705915

5. Søndergaard L, Kasner SE, Rhodes JF, et al; Gore REDUCE Clinical Study Investigators. Patent foramen ovale closure or antiplatelet therapy for cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(11):1033-1042. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1707404

6. Saver JL, Carroll JD, Thaler DE, et al; RESPECT Investigators. Long-term outcomes of patent foramen ovale closure or medical therapy after stroke. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(11):1022-1032. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1610057

7. Messé SR, Gronseth GS, Kent DM, et al. Practice advisory update summary: patent foramen ovale and secondary stroke prevention: report of the guideline subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2020;94(20):876-885. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000009443

8. Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, et al. 2021 guideline for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2021;52(7):e364-e467. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000375

9. Collado FMS, Poulin MF, Murphy JJ, Jneid H, Kavinsky CJ. Patent foramen ovale closure for stroke prevention and other disorders. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(12):e007146. doi:10.1161/JAHA.117.007146

10. Khairy P, O'Donnell CP, Landzberg MJ. Transcatheter closure versus medical therapy of patent foramen ovale and presumed paradoxical thromboemboli: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(9):753-760. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00010

11. Pristipino C, Sievert H, D'Ascenzo F, et al; European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI); European Stroke Organisation (ESO); European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA); European Association for Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI); Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC); ESC Working group on GUCH; ESC Working group on Thrombosis; European Haematological Society (EHA). European position paper on the management of patients with patent foramen ovale. General approach and left circulation thromboembolism. EuroIntervention. 2019;14(13):1389-1402. doi:10.4244/EIJ-D-18-00622

12. Rodés-Cabau J, Palacios A, Palacio C, et al. Assessment of the markers of platelet and coagulation activation following transcatheter closure of atrial septal defects. Int J Cardiol. 2005;98(1):107-112. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.03.022

13. Kovacevic P, Srdanovic I, Ivanovic V, Rajic J, Petrovic N, Velicki L. Late complications of transcatheter atrial septal defect closure requiring urgent surgery. Postepy Kardiol Interwencyjnej. 2017;13(4):335-338. doi:10.5114/aic.2017.71617

14. Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, et al; American Heart Association; American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2276-2293. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192218

15. Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123(23):2736-2747. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449

16. Kefer J, Carbonez K, Pierard S, et al. Antithrombotic therapy duration after patent foramen ovale closure for stroke prevention: impact on long-term outcome. J Interv Cardiol. 2022;2022:6559447. doi:10.1155/2022/6559447

17. Guedeney P, Farjat-Pasos JI, Asslo G, et al; AIR-FORCE Task Force. Impact of the antiplatelet strategy following patent foramen ovale percutaneous closure. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2023;9(7):601-607. doi:10.1093/ehjcvp/pvad023

18. Polzin A, Dannenberg L, Sophia Popp V, Kelm M, Zeus T. Antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel and aspirin after interventional patent foramen ovale/atrium septum defect closure. Platelets. 2016;27(4):317-321. doi:10.3109/09537104.2015.1096335

19. Krumsdorf U, Ostermayer S, Billinger K, et al. Incidence and clinical course of thrombus formation on atrial septal defect and patient foramen ovale closure devices in 1,000 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(2):302-309. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.030

20. Ravellette KS, Gornbein J, Tobis JM. Incidence of atrial fibrillation or arrhythmias after patent foramen ovale closure. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2023;3(1):101173. doi:10.1016/j.jscai.2023.101173