Operator Radiation Dose Comparing Left Radial Artery and Right Radial Artery Approaches Among Patients With Subclavian Tortuosity

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Operator radiation exposure (ORE) is one of the most adverse occupational hazards faced by interventional cardiologists. The presence of subclavian tortuosity can influence ORE.

Methods. This single-center retrospective study compared the cumulative radiation (CR) exposure in μSv and normalized radiation exposure (CR/DAP) of the primary operator during cardiac catheterization of all patients with subclavian tortuosity from left (LRA) and right radial artery approaches (RRA). ORE was measured at 4 anatomical locations: thorax, abdomen, left eye, and right eye.

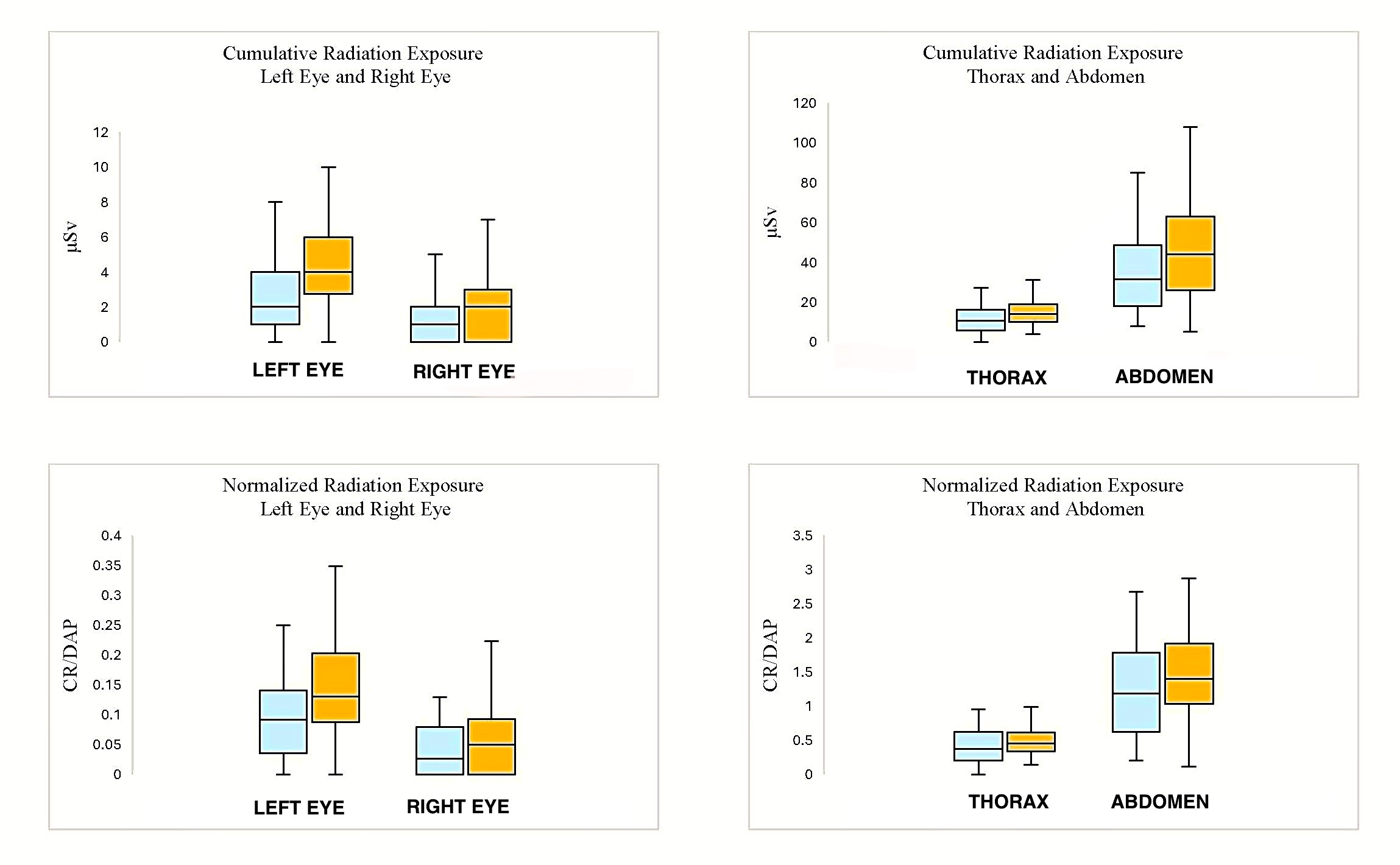

Results. CR dose was significantly higher in the RRA group than in the LRA group at the left eye (P = .004), right eye (P = .01), thorax (P = .01) and abdomen (P = .01). CR/DAP dose was significantly higher in the RRA group than in the LRA group at the left eye (P = .04) and right eye (P = .03).

Conclusions. In cases with subclavian tortuosity, the LRA was associated with less CR to the operator than the RRA. The LRA was also associated with less CR/DAP that persisted at the anatomical location of the left eye. The authors recommend operators have time thresholds to exchange for appropriate catheters in patients with subclavian tortuosity. Furthermore, operators should consider time thresholds to change access sites to avoid potential procedural complications and excessive fluoroscopic times.

Introduction

Radiation exposure is an occupational hazard of concern to interventional cardiologists. It is associated with left-sided brain tumors, cataracts, and thyroid disease.1 Selective coronary angiography from the radial approach is a common approach because it reduces bleeding complications for patients and costs for medical centers.2,3 However, the use of a radial artery approach has greater radiation exposure compared with a femoral artery approach.4

Subclavian tortuosity is an important cause for failure of transradial coronary procedures,5 and several studies report subclavian tortuosity as a reason for procedural failure in some patients. Although not statistically significant, there was a greater presence of subclavian tortuosity from the right radial artery approach (RRA) compared with the left radial artery approach (LRA).6,7 An observational study of percutaneous coronary procedures demonstrated a significantly greater presence of subclavian tortuosity in the RRA compared with the LRA. This study also found that the RRA was associated with a greater cumulative and normalized radiation exposure (CR/DAP) than the LRA at the thorax and wrist; most of the sample did not have subclavian tortuosity.8

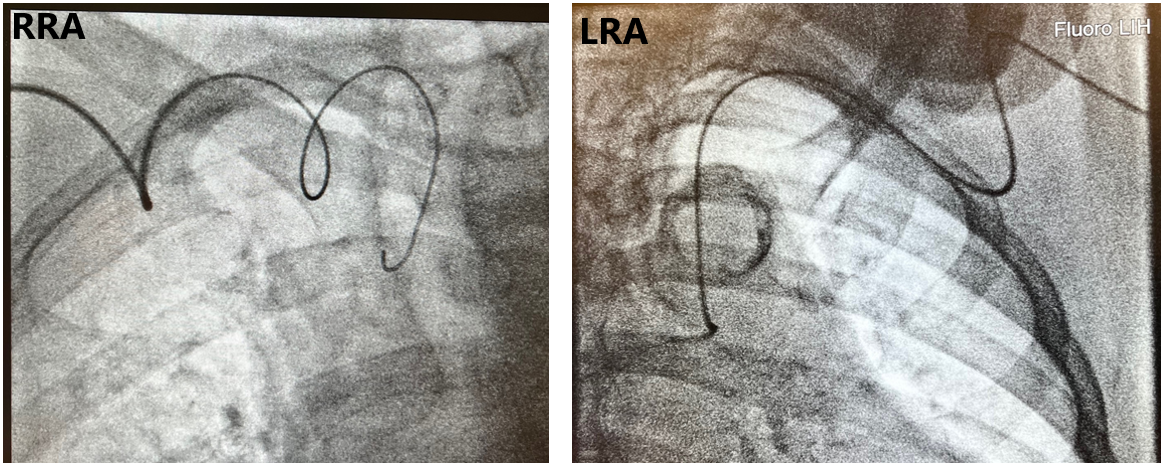

The presence of subclavian tortuosity can lead to greater procedural times, which can lead to greater operator radiation exposure (ORE). Studies assessing ORE for transradial coronary angiography have shown that use of the RRA is associated with greater ORE than use of the LRA.9,10 We hypothesize that the presence of subclavian tortuosity will also demonstrate greater ORE from the RRA than the LRA. We are unaware of any studies focusing on ORE among patients with subclavian tortuosity. In this study, we compared the cumulative and normalized ORE between the RRA and LRA in 4 regions—the left eye, right eye, thorax, and abdomen—in cases with subclavian tortuosity (Figure 1).

Methods

Setting

This is a retrospective secondary analysis from the HARRA randomized clinical trial conducted at a tertiary center.10 The HARRA trial compared the cumulative and normalized ORE between the LRA and RRA in 4 regions—the left eye, right eye, thorax, and abdomen—in cases of elective cardiac catheterization. The study included patients older than 18 years undergoing elective cardiac catheterization who were deemed suitable for a radial approach. Patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-STEMI, hemodynamic instability, previous coronary artery bypass grafts, arteriovenous fistulas for hemodialysis, and non-palpable radial pulses were excluded. Radiation was measured only during diagnostic selective coronary angiography. Radiation was not measured during percutaneous coronary interventions. The 13 operators had experience ranging from 4 to 30 years, and all had extensive experience using both LRA and RRA approaches. The presence of subclavian tortuosity was determined by the operator performing the procedure. Ethical approval was received from the institutional review board of the hospital. All participants provided written informed consent.

Procedures

All procedures were performed on the right side of the patient. The radial artery was accessed (conventional or “snuffbox”) using a modified Seldinger technique with an 18-gauge needle. A 10 or 16-cm slender radial sheath (Terumo) was inserted into the radial artery. A standardized protocol for coronary projections was employed. Four standard left coronary and 2 standard right coronary artery projections were taken. Catheter selection and additional cineangiograms were taken at the operator’s discretion.

RRA and LRA setup

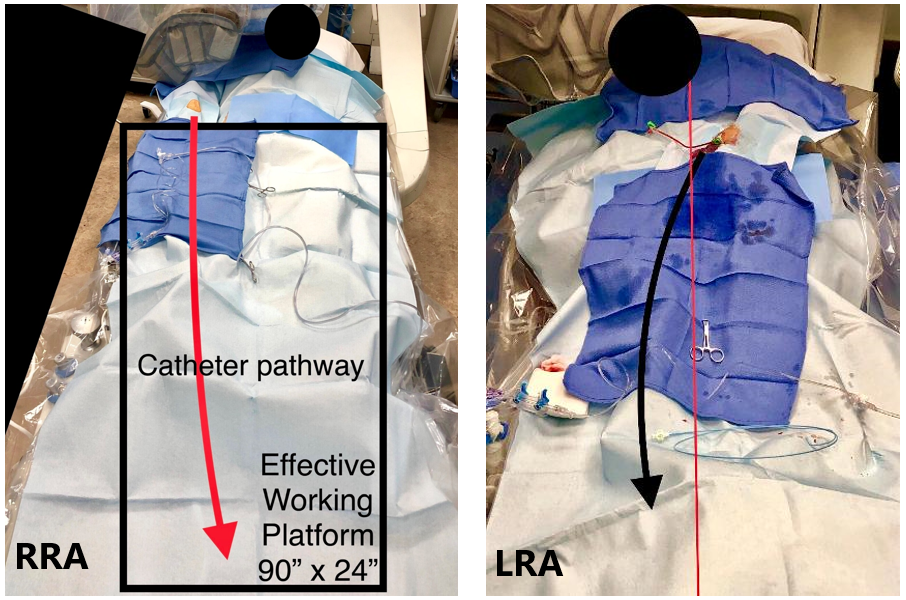

Hyperadduction was used for patients in the RRA group. The objective was to place the right wrist parallel with the right flank of the body. The arm was moved to a semi-adducted position and radial artery access was obtained. After access, the arm was hyperadducted and placed as close as possible to the body. For the LRA group, the left arm was adducted and placed on a standard swivel arm board. A radial access sleeve (Tesslagra Design Solutions) was placed over the arm to achieve circumferential sterility; radial access was then obtained. After access, the LRA was adducted so that the hub of the sheath was placed at the patient’s midline axis and the sleeve drape was clamped down to create tension toward the operator to minimize arm drift and promote ergonomics. Both approaches are shown in Figure 2.10

Radiation measurements and radiation safety measures

Four real-time radiation dosimeters (Raysafe i3 System) were positioned outside the operator’s lead at the thorax, abdomen, left eye, and right eye. Radiation was measured in microsieverts (µSv). Radiation dose measurements were transmitted to a dosimetry monitor that operators could not see. All operators wore the same radiation protection garments. Standard table-mounted shielding, and a standard ceiling-mounted lead shield with a lead skirt were used. Operators had the option to place the shields in the position they prefer. We used 2 fluoroscopic rooms, each with identical shielding arrangements and software producing the same radiation output algorithms. No supplementary radiation technologies were used. ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) etiquette was regularly used.11 Frequent collimation was used because it is the standard practice at our hospital.

Study outcomes and variables

The primary outcome was the radiation exposure of the primary operator at the left eye. This was measured both with the cumulative radiation exposure (CR) in microsieverts (μSv) and normalized by dose-area-product (DAP), expressed as (CR/DAP). Secondary outcomes were the CR and CR/DAP of the primary operator at the right eye, thorax, and abdomen.

Covariates included patient demographics: age (years), sex (female/male), race/ethnicity (White/non-White), height (cm), weight (kg), body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), and body surface area (m2). Patient medical and surgical variables were smoking status, hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and previous coronary angiography, all measured as no/yes. Procedure variables were DAP (cGy.cm2), fluoroscopic time (minutes), contrast amount delivered (cc), milligray (mGy), distal radial approach (no/yes), cineangiograms (number used), and catheters (number used).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics consisted of mean and SD for the continuous variables and frequency, and percentage for the categorical variables. Inferential parametric statistics of analysis of variance compared the continuous variables. The Pearson chi-square test compared the categorical variables except when the expected cell size was less than 5, where the Fisher’s exact test was used. For the outcome variables, an additional inferential non-parametric analysis of the Mann-Whitney U test was performed. All variables that were statistically different between the LRA and RRA approaches were included as covariates in the multivariate linear regression analyses. The thorax underwent logarithmic transformation because of the presence of skewness. As intention-to-treat analyses were used, the 3 patients with access-site switch were kept in the analyses at the original side to which they had been randomly assigned (1 patient from the LRA and 2 patients from the RRA). All P-values were 2-tailed with the alpha level for significance set at a P-value of less than 0.05. IBM SPSS Statistics Version 30 (IBM) was used for all analyses.

Results

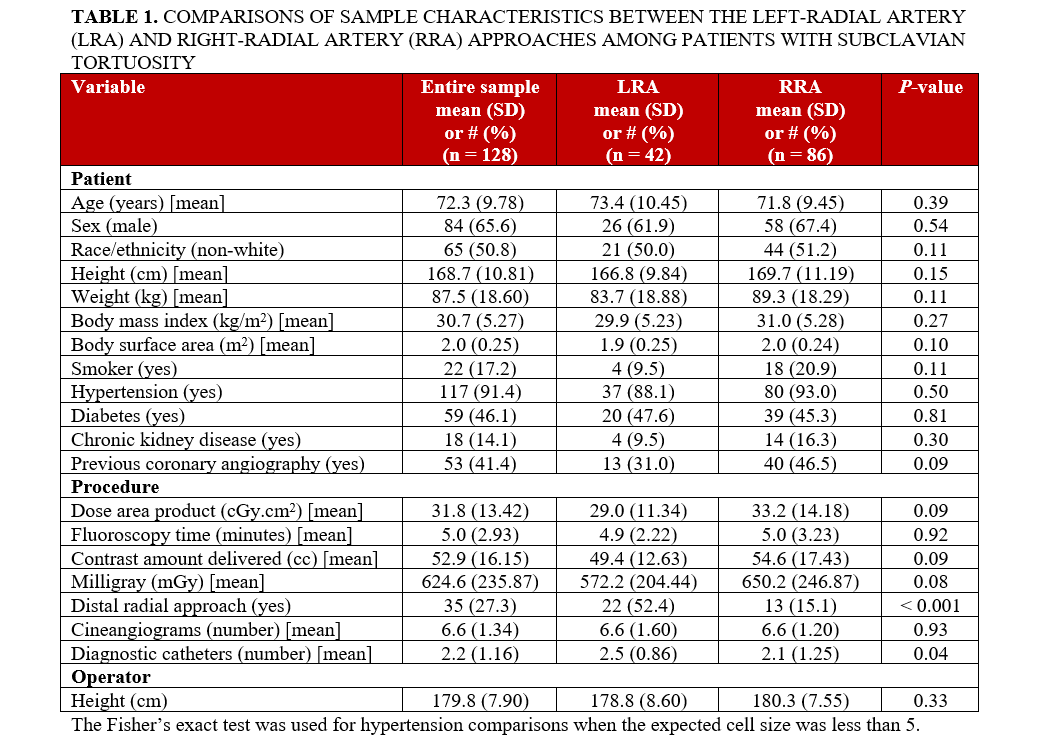

Of the patients with subclavian tortuosity, 32.9% (42) underwent the LRA approach and 67.2% (86) underwent the RRA approach. Comparisons of the sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 72.3 years, 65.6% (84) were male, and 50.8% (65) were of non-White race/ethnicity. In terms of medical history, 91.4% (117) of the patients had hypertension, and 46.1% (59) had diabetes. None of the patient variables significantly differed between the LRA and RRA approaches.

There were 2 procedure variables that significantly differed between the LRA and RRA approaches: the cases involving the LRA approach used the distal radial approach more often than the RRA cases, and the LRA cases used a greater number of diagnostic catheters compared with the RRA approach. There was access site crossover because of the presence of severe subclavian tortuosity for 3 patients (1 for LRA and 2 for RRA). For these 3 patients, the patient randomly assigned to the LRA approach had a fluoroscopic time of 9.2 minutes. The 2 patients randomly assigned to the RRA approach had fluoroscopic times of 4.0 and 5.1 minutes.

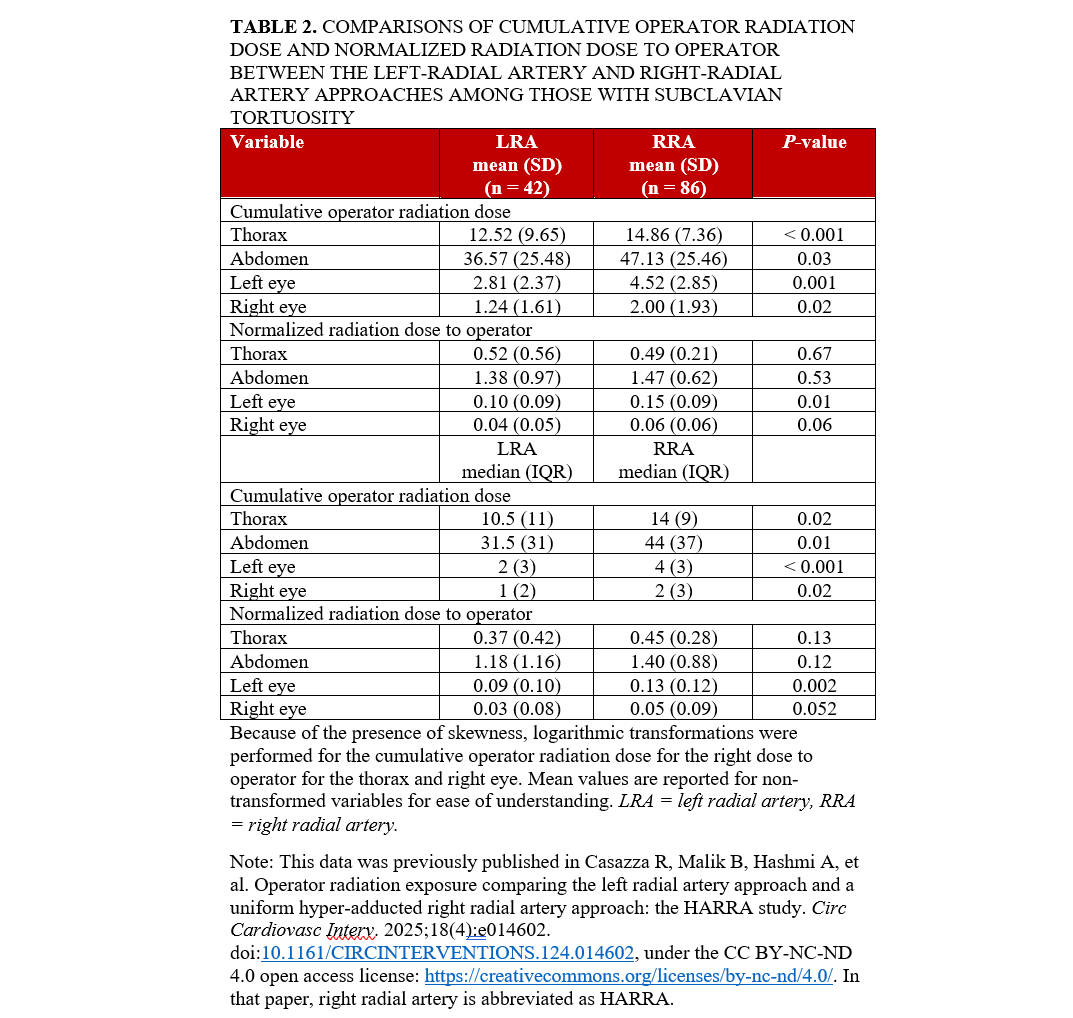

Table 2 shows univariate comparisons of the CR and CR/DAP doses to operators. The mean CR dose was significantly lower in the LRA group than in the RRA group at the thorax (P < .001), abdomen (P = .03), left eye (P < .001), and right eye (P = .02). The mean CR/DAP dose was significantly lower in the LRA group than in the RRA group at the left eye (P = .01). Median analyses for both the CR dose and the CR/DAP dose outcomes had similar significance patterns as with mean dose analyses (Figure 3).

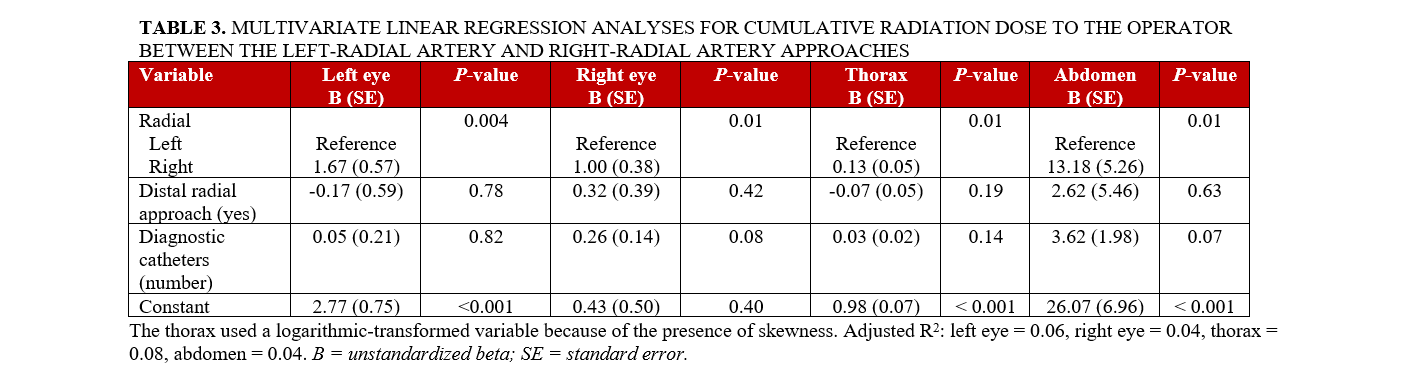

Multivariate linear regression analyses for CR and CR/DAP to operators encountering subclavian tortuosity are shown in Tables 3 and 4. The CR was significantly higher in the RRA group than in the LRA group at the left eye (P = .004), right eye (P = .01), thorax (P = .01), and abdomen (P = .01). The CR/DAP was significantly higher in the RRA group than in the LRA group at the left eye (P = .04) and right eye (P = .03).

Discussion

Our study demonstrates an association of lower cumulative ORE using an LRA at the thorax, abdomen, left eye, and right eye compared with an RRA in patients with subclavian tortuosity. There was also an association of lower normalized ORE at the level of the left and right eyes. Our study has similar findings to prior research suggesting that subclavian tortuosity has an effect on ORE.6-8 We add to the literature, demonstrating that, in patients with subclavian tortuosity, the LRA is associated with less cumulative exposure compared with the RRA at 4 anatomical locations.

Several elements may explain why the LRA was associated with less ORE. First, shielding from the LRA facilitates an oblique ceiling-mounted shield position as opposed to the RRA setup, where the shield is typically in a more perpendicular position, which can expose the operator to primary and tertiary scatter radiation. Second, when using the LRA, operators may be closer to the table-mounted shield, which can provide better protection from leakage radiation of the fluoroscopic unit. Operators using the LRA may also position the patient table lower than operators using the RRA, which increases the distance between the fluoroscopic unit and dosimeters, as well as dropping the radiation output from the fluoroscopic unit.12 Lastly, subclavian tortuosity can play a role in ORE.

The LRA was also associated with less CR/DAP at the level of the left and right eyes in patients with subclavian tortuosity. It is possible that shield migration contributed to an increase in normalized exposure using the RRA at the level of the eyes. As subclavian tortuosity becomes more pronounced, operators may be less attentive to strategic shield positioning and may be solely focused on catheter manipulation. When using the LRA, the ceiling-mounted shield infrequently moves out of position because of the logistics of operating from the right side of the patient table, which can account for the reductions. These findings are especially important as the left eye is at more risk of radiation-induced cataracts than the right eye because of its proximity to the patient and radiation source when operating from the right side of the patient.13-15

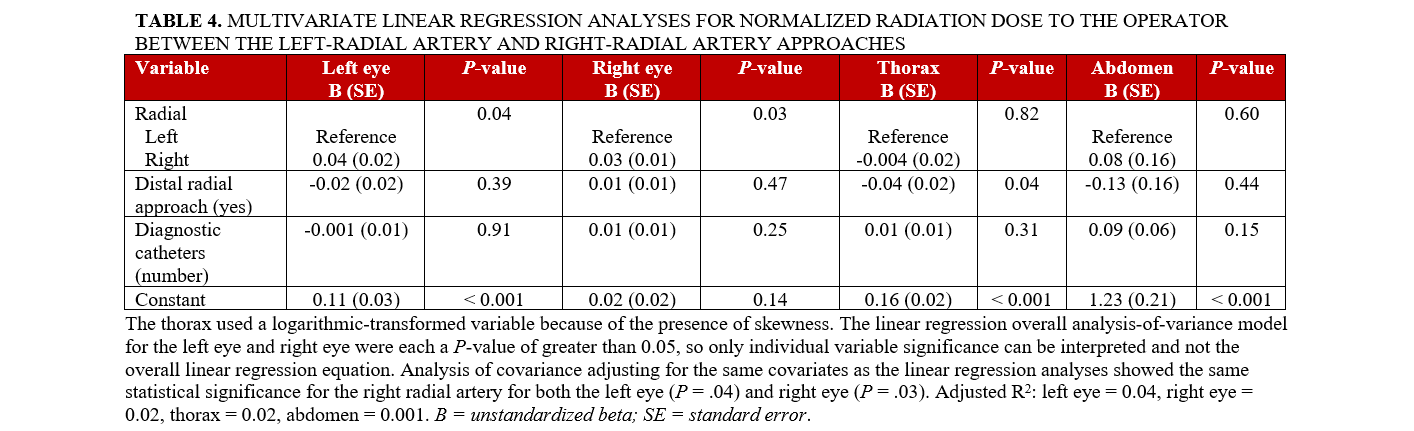

There are 3 important factors when considering subclavian tortuosity in terms of how it may impact ORE. First is the degree of tortuosity. Mild tortuosity may not have an impact on ORE, especially for experienced “radial-first” operators. However, as tortuosity becomes more pronounced, this can pose a problem for selective coronary engagement and guide support. As catheters move across the trachea fluoroscopically, the difficulty of catheter manipulation increases. Subclavian loops or an “elephant’s head” tortuosity can pose technical challenges for operators (Figure 4). Research suggests that, for catheters passing the spine greater than 1 cm on fluoroscopy, exchanging for Judkins catheters from universal radial approach catheters may provide faster coronary engagement.16 As the severity of tortuosity increases, this can add fluoroscopic time as well as ORE if strategic shield placement is not attended to by operators.

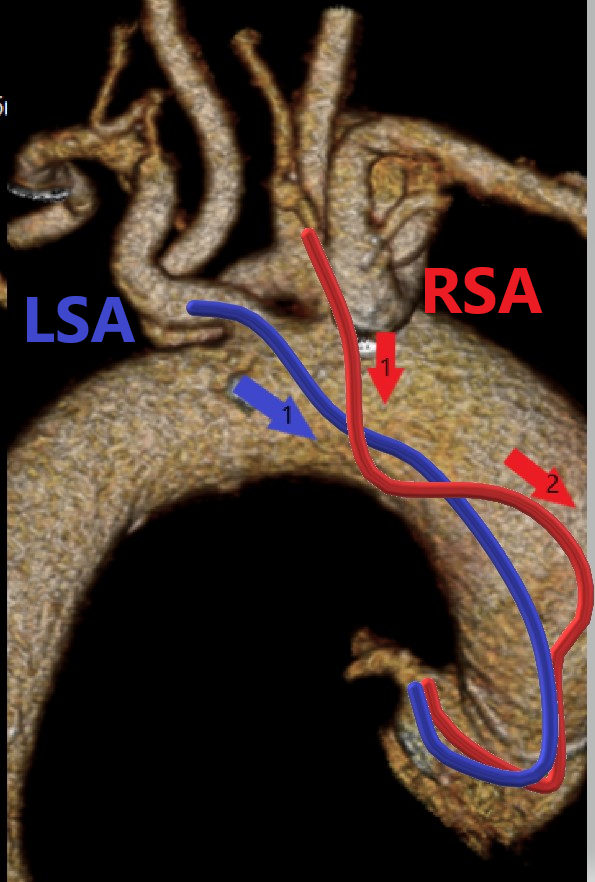

The second factor is the entry angle at the junction of the subclavian artery and the aorta. Aorto-innominate junction entry angles can pose technical challenges that may be more difficult compared with the left subclavian’s junction with the aorta. The passage of catheters from an LRA is similar to a femoral approach9 and may provide a more favorable angle when entering the ascending aorta, which can provide faster engagement into coronary ostia. There is typically 1 vector angle for catheters passing from the LRA as opposed to 2 or more vector angles using the RRA, which may increase technical difficulties, particularly depending on the severity of subclavian tortuosity (Figure 5).

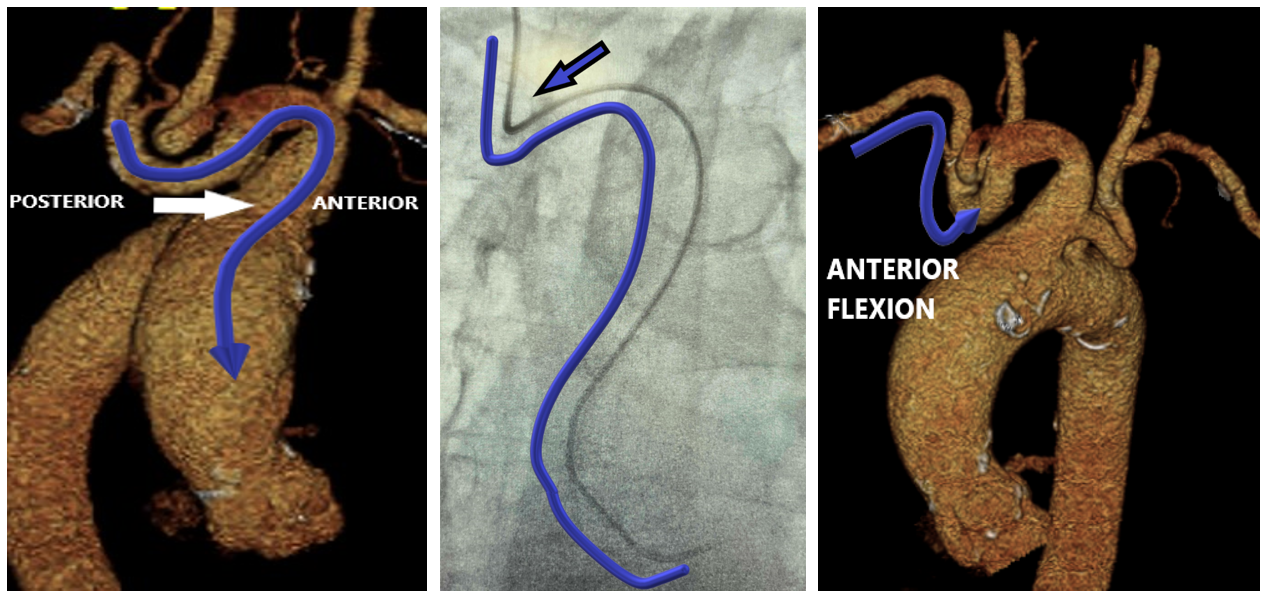

The third factor to consider is the anterior flexion of the right subclavian artery, which can be a technical concern. It arises from the brachiocephalic trunk with 2 consecutive vascular bifurcations at that level, which adds a dimension of tortuosity as it bends into the ascending aorta (Figure 6). Frequently, there are acute bends at the aorto-innominate junction, which create a contact point with the upper vasculature that causes a loss of catheter torque transmission. Anterior flexion of the left subclavian may pose less of an issue because of its direct takeoff from the aorta.

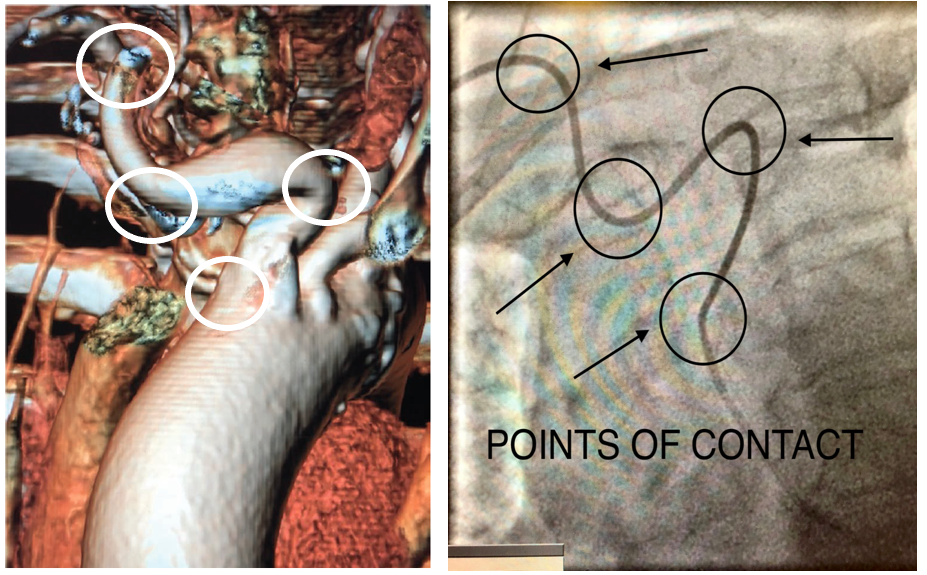

Subclavian tortuosity challenges can make a radial approach procedure arduous. Selective coronary angiography or interventions become increasingly difficult because of the torque being transmitted into the tortuosity rather than the tip of the catheter. This typically occurs because there are several points of contact with the catheter and the subclavian artery (Figure 7). This may lead to catheters “helicoptering” and even kinking. Operators should periodically look at the upper vasculature under fluoroscopy. Furthermore, operators should be vigilant in checking pressure waveforms, as this is an indicator of catheter kinking, which is more prevalent in patients with subclavian tortuosity. Operators should also have time thresholds to exchange catheters more suited for selective angiography and proper guide support if the catheter they are manipulating is unsuited. In addition, operators should have time thresholds to switch access sites to avoid procedural complications (ie, stroke) as well as excessive fluoroscopic times, which can ultimately have a direct impact on ORE.

Limitations

A strength of this study is that it is the first to compare ORE in cases with subclavian tortuosity. However, it does have several limitations. First, the study was conducted at a single center and may not be generalizable to other centers. Second, subclavian tortuosity was determined at the discretion of the operator; therefore, there is some degree of subjectivity. Future research should consider a dedicated trial evaluating ORE in patients with standardized subclavian tortuosity criteria. Third, we did not measure the time it takes to resolve cases with severe subclavian tortuosity before considering an access-site switch, nor did we measure the overall procedure time. Fourth, individual shielding positioning may have varied from operator to operator and may impact individual ORE doses. Fifth, as we did not collect data on the degree of subclavian tortuosity, we were unable to stratify patients by subclavian anatomy to understand the nuances of when LRA access may be preferred. Furthermore, a dedicated study describing degrees of subclavian tortuosity would make defining subclavian tortuosity more objective.

Conclusions

In cases with subclavian tortuosity, the LRA was associated with less CR exposure to the operator than the RRA. In addition, the LRA was associated with less persisting CR/DAP at the left and right eyes of the operators than the RRA. We recommend operators have time thresholds to exchange for appropriate catheters in patients with subclavian tortuosity. Furthermore, operators should consider time thresholds to change access sites to avoid potential procedural complications and excessive fluoroscopic times.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Richard Casazza, MAS1; Bilal Malik, MD1; Arsalan Hashmi, MD1; Joshua Fogel, PhD2; Enrico Montagna, RT (CI)1; Darren Gibson, RT1; Andres Palacio, RT (CI)1; Habiba Beginyazova, RT1; Robert Frankel, MD1; and Jacob Shani, MD1

From the 1Department of Cardiology, Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, New York; 2Department of Management, Marketing, and Entrepreneurship, Brooklyn College, Brooklyn, New York.

Disclosures: Mr Casazza is the director of R&D for Tesslagra Design Solutions. The remaining authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Address for correspondence: Richard Casazza, MAS, Department of Cardiology, Maimonides Medical Center, 4802 10th Avenue, Brooklyn, NY, 11219, USA. Email: rcasazza@maimo.org

References

- Kumar G, Rab ST. Radiation safety for the interventional cardiologist—a practical approach to protecting ourselves from the dangers of ionizing radiation. American College of Cardiology. January 4, 2016. Accessed April 27, 2025. https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2015/12/31/10/12/radiation-safety-for-the-interventional-cardiologist

- Romagnoli E, Biondi-Zoccai G, Sciahbasi A, et al. Radial versus femoral randomized investigation in ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: the RIFLE-STEACS (Radial Versus Femoral Randomized Investigation in ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(24):2481-2489. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.017

- Rinfret S, Kennedy WA, Lachaine J, et al. Economic impact of same-day home discharge after uncomplicated transradial percutaneous coronary intervention and bolus-only abciximab regimen. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3(10):1011-1019. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2010.07.011

- Sciahbasi A, Frigoli E, Sarandrea A, et al. Radiation exposure and vascular access in acute coronary syndromes: the RAD-Matrix trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(20):2530-2537. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.018

- Burzotta F, Brancati MF, Trani C, et al. Impact of radial-to-aorta vascular anatomical variants on risk of failure in trans-radial coronary procedures. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;80(2):298-303. doi:10.1002/ccd.24360

- Kawashima O, Endoh N, Terashima M, et al. Effectiveness of right or left radial approach for coronary angiography. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2004;61(3):333-337. doi:10.1002/ccd.10769

- Norgaz T, Gorgulu S, Dagdelen S. A randomized study comparing the effectiveness of right and left radial approach for coronary angiography. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;80(2):260-264. doi:10.1002/ccd.23463

- Sciahbasi A, Rigattieri S, Sarandrea A, et al. Determinants of operator radiation exposure during percutaneous coronary procedures. Am Heart J. 2017;187:10-18. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2017.02.012

- Dominici M, Diletti R, Milici C, et al. Operator exposure to x-ray in left and right radial access during percutaneous coronary procedures: OPERA randomised study. Heart. 2013;99(7):480-484. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302895

- Casazza R, Malik B, Hashmi A, et al. Operator radiation exposure comparing the left radial artery approach and a uniform hyper-adducted right radial artery approach: the HARRA study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv: 2025;18(4):e014602. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.124.014602

- Radiation and your health. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. February 15, 2024. Accessed April 27, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/radiation-health/about/index.html

- Pancholy SB, Joshi P, Shah S, Rao SV, Bertrand OF, Patel TM. Effect of vascular access site choice on radiation exposure during coronary angiography: the REVERE trial (Randomized Evaluation of Vascular Entry Site and Radiation Exposure). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(9):1189-1196. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2015.03.026

- Hamada N. Ionizing radiation sensitivity of the ocular lens and its dose rate dependence. Int J Radiat Biol. 2017;93(10):1024-1034. doi:10.1080/09553002.2016.1266407

- Rose A, Rae WID, Sweetlove MA, Ngetu L, Benadjaoud MA, Marais W. Radiation induced cataracts in interventionalists occupationally exposed to ionising radiation. SA J Radiol. 2022;26(1):2495. doi:10.4102/sajr.v26i1.2495

- Jacob S, Boveda S, Bar O, et al. Interventional cardiologists and risk of radiation-induced cataract: results of a French multicenter observational study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(5):1843-1847. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.04.124

- Case BC, Yerasi C, Forrestal BJ, et al. Right transradial coronary angiography in the setting of tortuous brachiocephalic/thoracic aorta ("elephant head"): impact on fluoroscopy time and contrast use. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;99(2):418-423. doi:10.1002/ccd.29470