Long-Term Study of Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Paravalvular Leak Closure for Hemolysis

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Objectives. Paravalvular leak (PVL) is a complication of valve replacement that may result in hemolytic anemia. This study evaluated the long-term impact of transcatheter PVL closure (TPVLC) on hemolysis markers in affected patients.

Methods. This multicenter study included 39 patients who underwent TPVLC for hemolysis from February 2013 to March 2024. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), hemoglobin (Hb) and indirect bilirubin were assessed at baseline and at 1, 6, 12, and 24 months. A subgroup of patients who had received preprocedural blood transfusions was also analyzed. Secondary endpoints included procedure-related hemolysis and preprocedural predictors of hemolysis compared with a cohort treated for heart failure.

Results. In the overall cohort (n = 39), TPVLC resulted in a significant improvement in hemolysis markers. Indirect bilirubin levels significantly decreased from the first month (P = .001), while LDH levels showed a significant reduction from 6 months onwards (P = .02). Hb levels significantly increased from the first month (P = .009). In transfused patients, both LDH and indirect bilirubin levels significantly decreased from the first month (P = .006 and P = .005, respectively), whereas Hb levels demonstrated a significant increase from 6 months onwards (P = .011). Procedure-related hemolysis occurred in 3 (7.7%) patients. Predictors of hemolysis included mechanical prostheses (P = .008), mitral PVL (P = .002), and chronic kidney disease (P = .001).

Conclusions. TPVLC significantly improves hemolysis markers over long-term follow-up.

Introduction

Paravalvular leak (PVL) is a major complication following surgical or transcatheter valve replacement that is caused by an incomplete seal between the sewing ring and the native annulus of the prosthetic valve. While most paravalvular defects remain asymptomatic, 1% to 3% of patients may develop symptoms of heart failure or hemolysis, which can adversely impact their survival.1,2 When the surgical risk for redo surgery is considered to be high, a transcatheter approach is recommended. According to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology guidelines, transcatheter PVL closure (TPVLC) is an effective alternative for patients with prosthetic valves, symptomatic heart failure (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class III–IV), and/or persistent hemolytic anemia, provided their anatomy is suitable for percutaneous treatment at specialized centers.3,4 The long-term outcome of the transcatheter closure technique, especially on hemolysis, has been debated. Several studies have investigated the bidirectional effects of TPVLC on hemolysis, consistently underscoring the importance of achieving complete leak closure for optimal outcomes.5-7

In the current study, we retrospectively analyzed the short- and long-term outcomes of patients who underwent TPVLC with hemolysis as the primary indication.

Methods

Study population

This study was conducted across multiple centers and included patients who consecutively underwent transcatheter interventions for PVL to manage hemolysis. The patients were treated at 5 hospitals in Greece—Sotiria Hospital (Athens), Hippokration Hospital (Athens), Hygeia Hospital (Athens), Interbalkan Medical Center (Thessaloniki), and Aghios Loukas Hospital (Thessaloniki)—from February 2013 to March 2024. Exclusion criteria included anemia attributed to causes other than hemolysis, such as gastrointestinal bleeding (eg, peptic ulcer disease, colorectal cancer), malignancies (eg, hematologic or solid tumors), chronic kidney disease, nutritional deficiencies (eg, iron, vitamin B12, or folate deficiency), or bone marrow disorders (eg, aplastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndromes). Data collection was performed by local investigators, anonymized, and entered into a centralized PVL registry. This registry included details such as baseline clinical characteristics, imaging assessments (eg, echocardiography, multislice imaging, and computed tomography), procedural specifics, and short- and long-term outcomes. At each center, the local heart team, which consisted of interventional cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and imaging specialists, was responsible for determining the necessity of transcatheter intervention, as well as the technical strategy and access route for each case. The clinical follow-up was evaluated either by telephone or physical visit. The study received approval from the institutional ethics committee and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The authors confirm that informed consent was obtained from all the patients for the study described in the manuscript and for the publication of their data.

Endpoints and definitions

The primary endpoint of this study was the evaluation of both short- and long-term changes in hemolysis indices—specifically lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), hemoglobin (Hb), and indirect bilirubin—among patients with hemolysis undergoing TPVLC. These biomarkers were assessed at 1, 6, 12, and 24 months post-procedure and compared to baseline values in order to monitor the course of hemolytic anemia over time. Additionally, a subgroup analysis was conducted in patients with hemolysis who had received blood transfusions preoperatively to evaluate whether transfusion status influenced the post-procedural evolution of hemolysis.

Secondary endpoints included the occurrence of TPVLC-related hemolysis, which represents a worsening of the pre-existing PVL and was defined as an increase in LDH activity of at least 100 IU/L compared with baseline at any follow-up point, as established in a previously published study.8 Additionally, the study focused on identifying preoperative factors that may predispose patients to hemolysis; this was investigated through a comparative analysis between patients who developed hemolysis and those who underwent PVL closure primarily because of heart failure, using data from a unified institutional database.

Hemolytic anemia was defined as anemia accompanied by elevated hemolysis indices after excluding other causes such as gastrointestinal bleeding, malignancies, chronic kidney disease, nutritional deficiencies or bone marrow disorders. These markers included Hb concentration, indirect bilirubin levels, and LDH levels of greater than 400 U/L. The transfusion criteria, both pre- and postprocedural, were applied to patients with Hb levels of less than 10 g/dL, particularly when accompanied by symptoms of anemia (eg, fatigue, dyspnea consistent with NYHA functional class III or IV). The final decision was based on the clinical judgment of the attending cardiologist, taking into consideration the overall patient status and ongoing evidence of hemolysis. Clinical success in this context was defined as a sufficient reduction in hemolysis to maintain transfusion independence for at least 6 months following the intervention. Technical success was defined as the effective deployment and stable implantation of the closure device, resulting in a greater than 90% reduction of the PVL cross-sectional area, which corresponds to mild PVL (less than 10%) as assessed by transthoracic echocardiography (TTE). PVL severity was determined using semi-quantitative echocardiographic criteria according to the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) recommendations.9 All definitions were based on previously published studies.5,8-13

TPVLC techniques

TPVLC techniques vary based on valve type and anatomy. The anterograde transeptal approach is most common for mitral valves, especially for defects in the anterolateral position. If unfeasible, transapical access or an arteriovenous loop may be used. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) guides the procedure, confirming device placement and valve function. For aortic valves, retrograde transfemoral access is typically employed.14-17

TTE is the primary method for assessing the severity and location of the PVL. Severity is determined by the ratio of sewing ring circumference to suture dehiscence length, with a ratio of less than 10% indicating mild, between 10% and 20% moderate, greater than 20% severe, and greater than 40% suggesting valve instability. Clinically significant PVL is defined as at least moderate regurgitation with symptoms of heart failure and/or hemolysis. TEE provides further evaluation and guides procedures. Cardiac computed tomography may also be used to map the defect, detailing its size, shape, and location relative to the surrounding structures.18

Device selection

The choice of closure device depends on the size and shape of the paravalvular regurgitation; operators aim for precise closure without affecting prosthetic valve function. The most commonly used devices are from the Amplatzer family (Abbott), including the Amplatzer Vascular Plug II (AVP II), the Amplatzer Valvular Plug III (AVP III) and the Amplatzer Vascular Plug IV (AVP IV), as well as the Amplatzer Duct Occluder I (ADO I) and Amplatzer Duct Occluder II (ADO II), the Amplatzer Septal Occluder and the Amplatzer Muscular VSD Occluder. Among these, the AVP III is the only CE-marked device approved for PVL closure. Additionally, the Occlutech PLD Occluder, designed specifically for PVL closure, is available in Europe.19-21

Statistical analysis

The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Continuous variables are presented as means (± SD), and categorical variables are shown as frequencies and percentages. For skewed distributions, medians (IQR) are reported. Parametric and non-parametric continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t-test and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, respectively. Categorical variables were analyzed with x2 tests or the Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was set at a P-value of less than or equal to 0.05, with a 95% CI. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier curves. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software, Version 20 (IBM).

Results

Patient and procedural characteristics

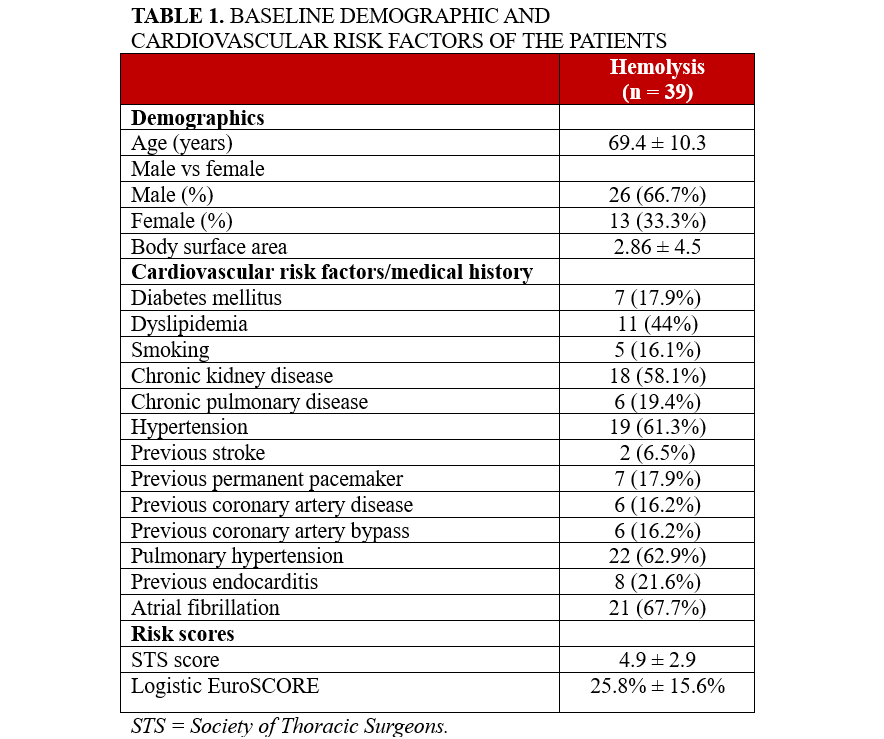

The patients were selected from a unified multicenter database of individuals who underwent transcatheter paravalvular leak closure with hemolysis or heart failure symptoms as the primary indication. Following the application of exclusion criteria, a total of 39 patients from 5 Greek centers who underwent transcatheter closure of paravalvular regurgitation to manage hemolytic anemia between February 2013 and March 2024 were included in the study. The duration of follow-up was 15 ± 9 months. The mean age was 69.4 ± 10.3 years, and 26 (66.7%) of the patients were male. The mean Society of Thoracic Surgery-Predicted Risk Of Mortality (STS-PROM) score was 4.9 ± 2.9 and the mean European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (Logistic EuroSCORE) was 25.8% ± 15.6%. Detailed demographic data, cardiovascular risk factors, and surgical risk scores are presented in Table 1.

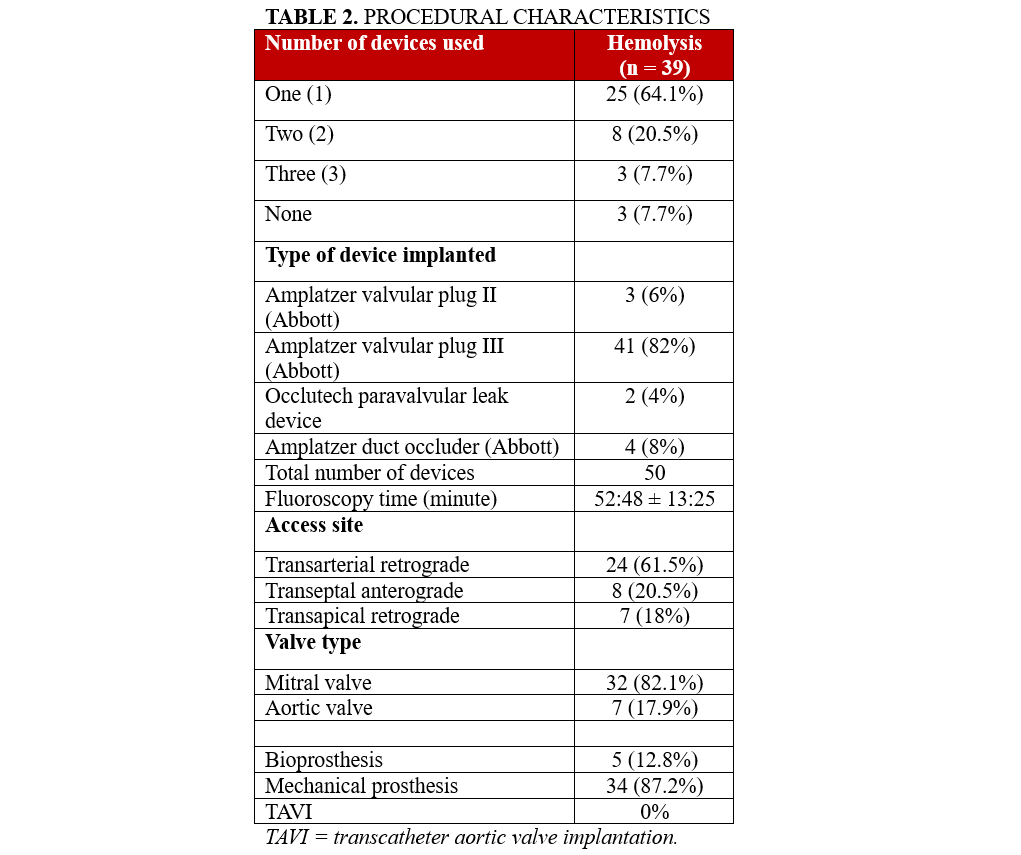

Overall, 34 (87.2%) of the patients had previously undergone surgical valve replacement with a mechanical valve, while 5 (12.8%) had received a bioprosthetic valve. None of the patients had undergone transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVΙ). The paravalvular leak was located at the mitral valve position in 32 (82.1%) of the patients and at the aortic valve position in 7 (17.9%). A total of 50 paravalvular leak closure devices were implanted. Specifically, 25 (64.1%) of the patients received 1 device, 8 (20.5%) received 2 devices and 3 (7.7%) required 3. In 3 (7.7%) cases, implantation was not possible because of anatomical challenges.

Of the 50 implanted devices, 41 (82.0%) were AVP III devices, followed by 4 (8%) ADO devices, 3 (6%) AVP II devices, and 2 (4%) Occlutech devices. Access site varied, with 24 (61.5%) patients undergoing transarterial retrograde access, 8 (20.5%) via transseptal anterograde and 7 (18%) via transapical retrograde access. These perioperative characteristics are detailed in Table 2.

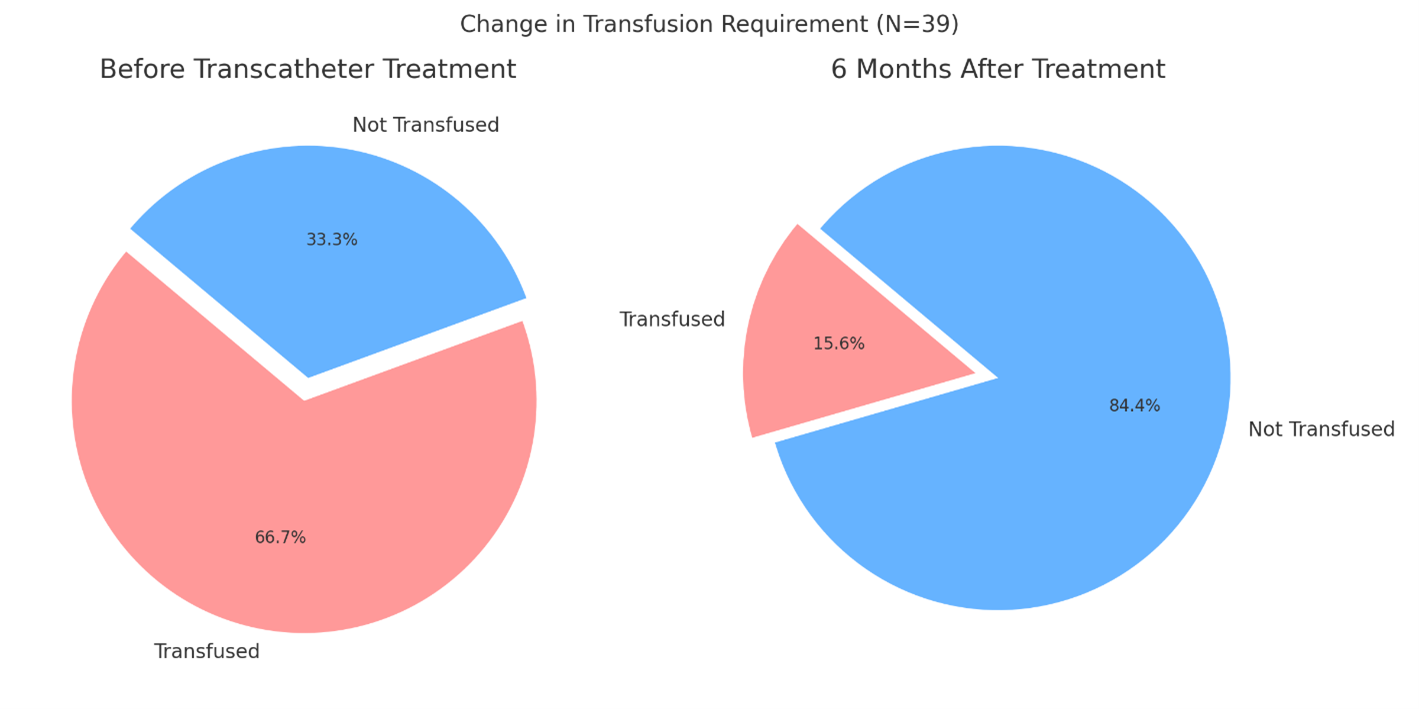

Prior to transcatheter treatment, 26 (66.7%) patients required transfusions, compared with 6 (15.6%) at 6 months post-procedure (P < .001) (Figure 1). Clinical success, defined as not needing a transfusion for at least 6 months, was achieved in 33 (84.4 %) patients. The technical success was 35 (89.7%). The rates of remaining moderate paravalvular leak were 34 (87.2%) preprocedural vs 2 (5.1%) at discharge (P < .001).

Outcomes

Primary outcome

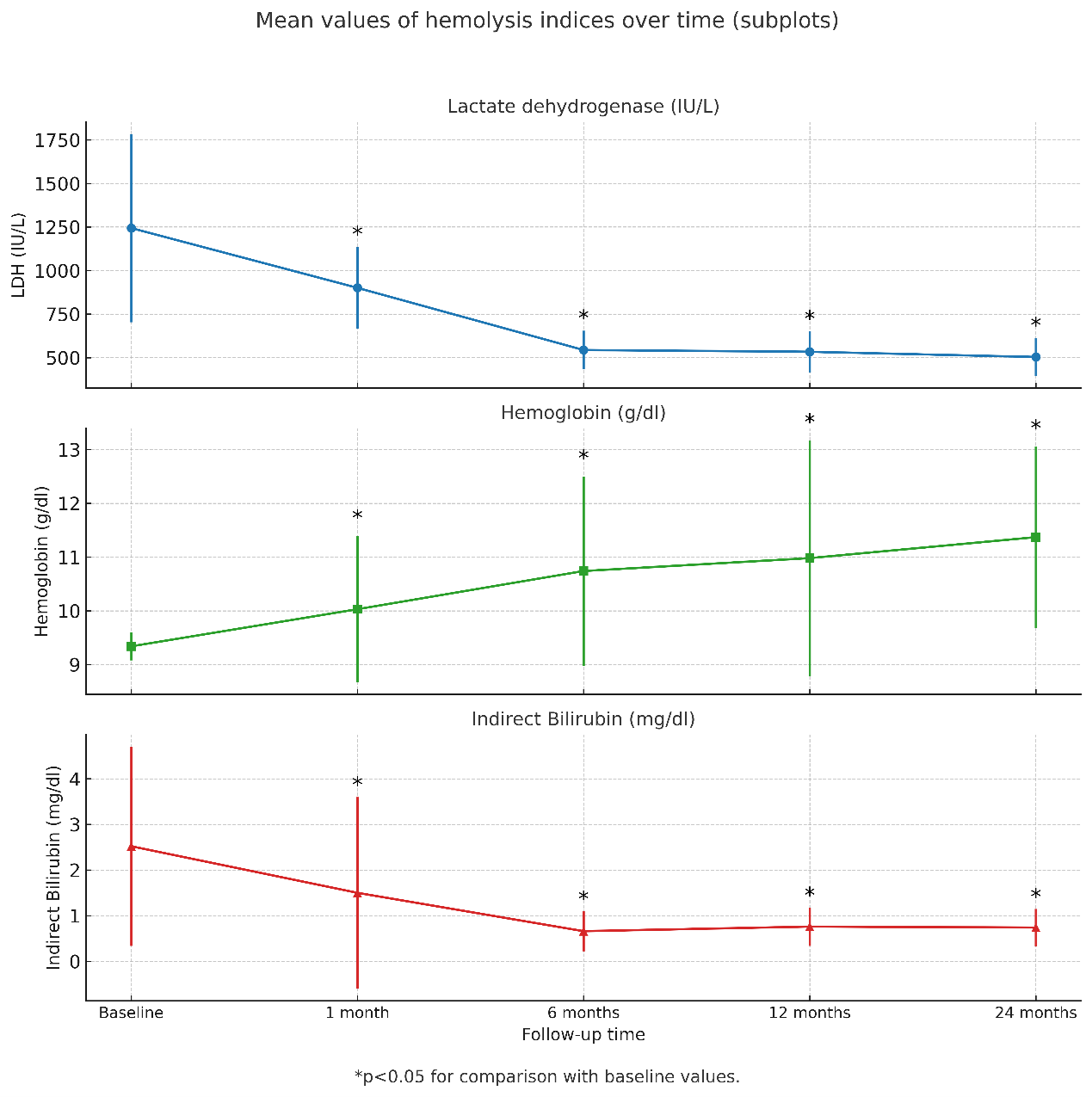

The mean preprocedural LDH was 1289 ± 540IU/L. Although reductions at 1 month (LDH 901 ± 235 IU/L, P = .141) were not statistically significant, a remarkable decrease was observed at 6 months (LDH 544 ± 111 IU/L, P = .020), 12 months (LDH 534 ± 117 IU/L, P = .019), and 24 months (LDH 504 ± 109 IU/L, P = .010). Hb levels significantly changed from preprocedural values (Hb 9.34 ± 0.26 g/dL) at 1 month (Hb 10.03 ± 1.36 g/dL, P = .009), 6 months (Hb 10.74 ± 1.76 g/dL, P = .001), 12 months (Hb 10.98 ± 2.19 g/dL, P = .009), and 24 months (Hb 11.37 ± 1.69 g/dL, P = .001). Indirect bilirubin, with a baseline of 2.52 ± 1.99 mg/dL, showed significant reductions at all time points: 1 month (1.50 ± 2.1 mg/dL, P = .001), 6 months (0.66 ± 0.44 mg/dL, P = .005), 12 months (0.76 ± 0.42 mg/dL, P = .005), and 24 months (0.74 ± 0.41 mg/dL, P = .004). All recordings in hemolysis indices over time, compared with preprocedural levels, are illustrated in Figure 2.

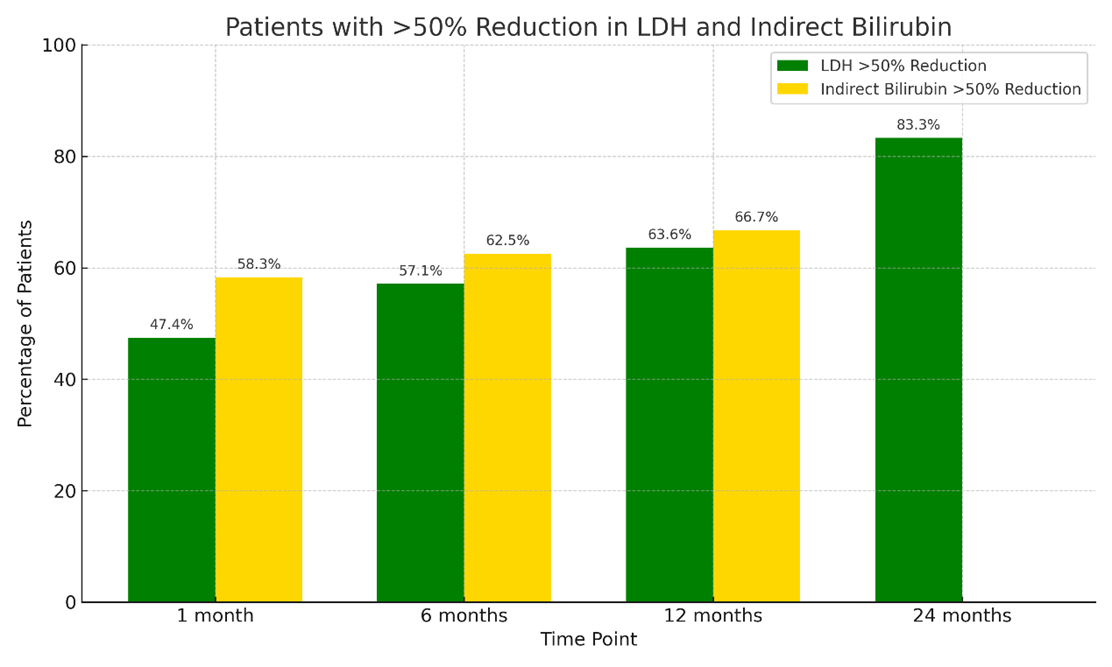

A greater than 50% reduction in LDH and indirect bilirubin from baseline was assessed at various time points. The proportion of patients who achieved a greater than 50% reduction in LDH was 18 (47.4%) patients at 1 month, 22 (57.1%) at 6 months, 25 (63.6%) at 12 months, and 32 (83.3%) at 24 months. Similarly, a greater than 50% reduction in indirect bilirubin was observed in 23 (58.3%) patients at 1 month, 24 (62.5%) at 6 months, 26 (66.7%) at 12 months, and 32 (81.1%) at 24 months. (Figure 3).

Out of 39 patients undergoing PVL closure, 26 (66.7%) required blood transfusions prior to the procedure. In this transfusion-dependent subgroup, LDH levels significantly decreased from preprocedural values (1453 ± 879 IU/L) at 1 month (617 ± 104 IU/L, P = .006), 6 months (388 ± 213 IU/L, P = .027), 12 months (494 ± 285 IU/L, P = .090), and 24 months (481 ± 170 IU/L, P = .045). Hb levels showed an increase from baseline (8.44 ± 1.14 g/dL) at 1 month (10.08 ± 1.4 g/dL, P = .070), 6 months (10.87 ± 1.75 g/dL, P = .011), 12 months (10.96 ± 2.11 g/dL, P = .025), and 24 months (11.34 ± 1.92 g/dL, P = .008). Indirect bilirubin showed a similar pattern, showing a decline from baseline (3.12 ± 2.52 mg/dL) at 1 month (2.00 ± 2.39 mg/dL, P = .005), 6 months (0.59 ± 0.35 mg/dL, P = .003), 12 months (0.70 ± 0.37 mg/dL, P = .002), and 24 months (0.71 ± 0.4 mg/dL, P = .005).

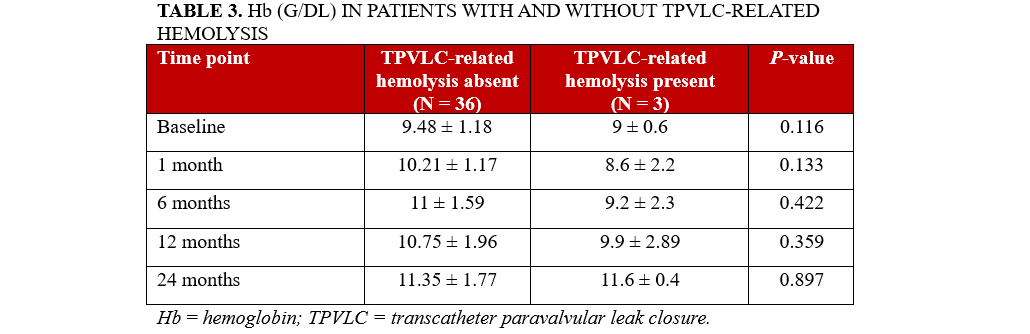

Secondary endpoints

There were 3 (7.7%) patients who experienced TPVLC-related hemolysis during the mean follow-up period of 15 ± 9 months (Table 3). A comparison of the baseline clinical and demographic parameters of patients undergoing transcatheter TPVLC with hemolysis (n = 39) to those with heart failure (n = 32) as the primary indication could help identify the pre-procedural factors that may contribute to the development of hemolysis prior to intervention.

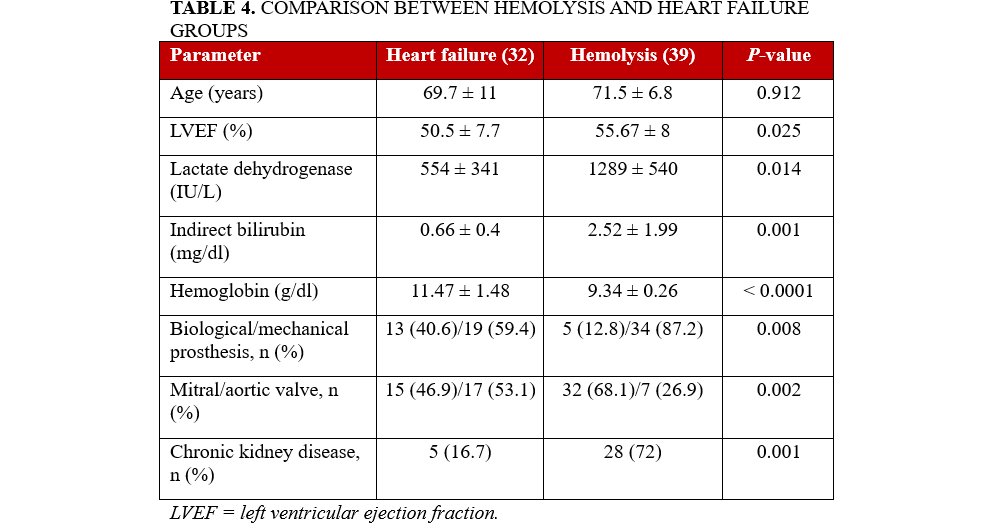

Patients in the hemolysis group exhibited a lower mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (50.5 ± 7.7% vs 55.7 ± 8.0%, P = .025), elevated LDH levels (1289 ± 540 vs 554 ± 341 IU/L, P = .014), increased indirect bilirubin concentrations (2.52 ± 1.99 vs 0.66 ± 0.40 mg/dL, P = .001), and lower Hb values (9.34 ± 0.26 vs 11.47 ± 1.48 g/dL, P < .0001) compared with the heart failure cohort. Furthermore, mechanical prosthetic valves were more prevalent in the hemolysis group (87.2% vs 59.4%, P = .008), as was mitral valve involvement (68.1% vs 46.9%, P = .002) and the presence of chronic kidney disease (72% vs 16.7%, P = .001) (Table 4).

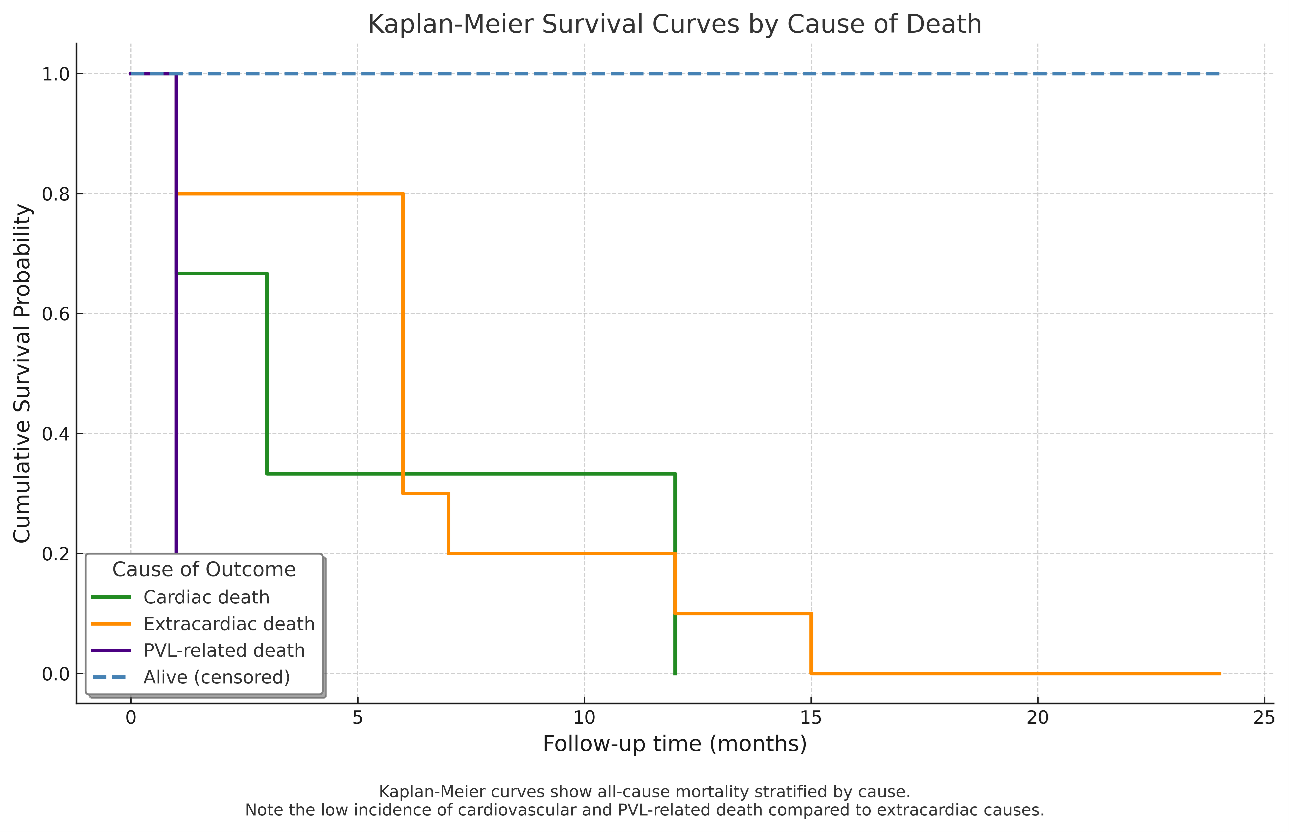

Survival

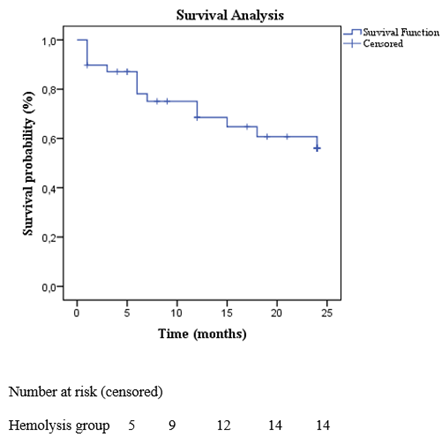

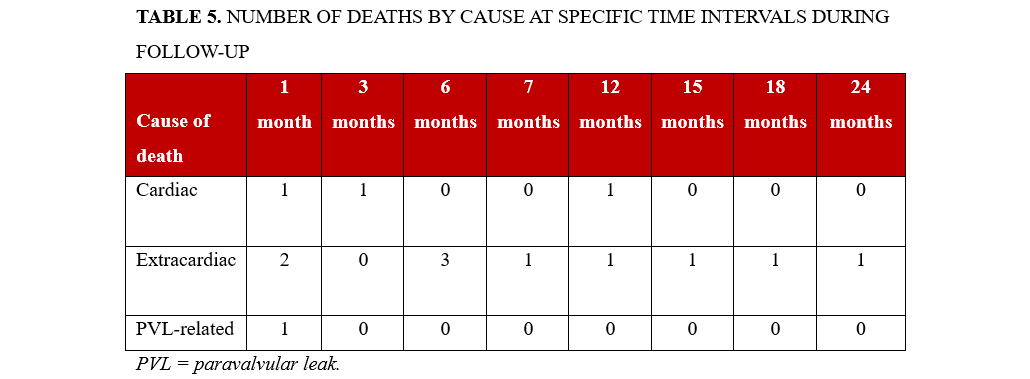

The Kaplan-Meier-estimated survival rate was 64.1%, corresponding to 25 out of 39 patients, over a follow-up period of 15 ± 9 months. During this time, 14 patients (35.9%) died. Mortality occurred as follows: 1 patient (2.6%) within the first month, 5 patients (12.8%) within 6 months, 11 patients (28.2%) within 12 months and 14 patients (35.9%) within 24 months (Figure 4). The primary causes of death were myelodysplastic syndrome (3 patients, 7.8%), septic shock or infection (3 patients, 7.8%), end-stage kidney disease (2 patients, 5.2%), complications from hip fracture surgery (1 patient, 2.6%), suicide (1 patient, 2.6%), acute decompensated right ventricular failure with liver dysfunction (1 patient, 2.6%), acute decompensated left ventricular failure (2 patients, 5.2%) and refractory hemolysis leading to multiple organ dysfunction (1 patient, 2.6%) (Figures 4 and 5, Table 5).

Discussion

This study highlights the clinical value of TPVLC in patients presenting with hemolysis. The intervention led to consistent and durable improvements in hemolysis markers, along with a substantial reduction in transfusion dependence. These benefits were sustained in the long term and were achieved despite the complex comorbidity profile of the treated population.

Our findings align with previous studies that focused on hemolysis improvement following TPVLC. Several studies have explored the 2-way effects of TPVLC on hemolysis, often highlighting the importance of achieving complete leak closure for optimal outcomes.5,6 Smolka et al studied 79 patients with PVL-related heart failure and hemolysis, demonstrating that TPVLC significantly improved hemolysis markers and Hb levels. Transfusion needs were notably reduced, especially when over 90% of the leak was sealed. Incomplete closure was linked to ongoing hemolysis and continued transfusion requirements. These benefits, including LDH reduction, lasted over 6 months. The study also identified mitral valve involvement and calcification as predictors of preprocedural hemolysis, and reported 14 cases of hemolysis related to the procedure itself.8 A case study by Abuelatta et al also underscored the unclear correlation between the size of a PVL and the severity of hemolysis; small defects can result in severe hemolysis, whereas larger leaks may not necessarily lead to hemolysis. Mild residual PVL can cause significant hemolytic anemia, which may be correctable through percutaneous closure of the leak. The development of dedicated devices for PVL closure is necessary to enhance the outcomes of percutaneous PVL repair.22 A multicenter registry by Hascoet et al identified incomplete PVL closure as a key factor associated with reduced clinical success in patients with hemolysis, underscoring the importance of achieving complete sealing.

Technical outcomes have improved with operator experience and dedicated closure devices. Nonetheless, the presence of hemolytic anemia and mechanical prostheses remains a predictor of less favorable results after TPVLC.23 Another study evaluating the impact of TPVLC found a reduction in transfusion requirements from 34% pre-procedure to 21% post-procedure, indicating improved control of hemolysis-related anemia. The intervention was associated with modest improvements in hemolysis markers, an increase in Hb levels, and decreased reliance on blood transfusions.24 Onorato et al analyzed the outcomes of TPVLC, reporting that the proportion of patients requiring hemolysis-related blood transfusions decreased from 35.5% to 3.8% in mitral valve patients and from 8.1% to 0% in aortic valve patients at 180 days post-procedure.25 In an analysis involving patients who underwent TPVLC, postprocedural hemolytic anemia was identified in 14 out of 129 patients who survived the procedure, with only 1 case showing worsening of pre-existing hemolysis.26 Burnard et al noted that while TPVLC carries a moderate complication risk, long-term survival in patients with hemolysis was strongly associated with complete leak resolution. In contrast, incomplete closure or ongoing hemolysis was linked to worse survival and increased rehospitalization due to heart failure.27 Another study emphasized the importance of controlling hemolysis to enhance survival, especially in patients with mitral or aortic PVLs. While survival tended to improve after closure, outcomes were influenced by leak complexity and the patient's overall clinical condition.28

Our analysis demonstrated a significant early and sustained hematologic improvement following PVL closure. LDH levels decreased markedly as early as 6 months post-intervention, with further reductions observed at 12 and 24 months. Hb and indirect bilirubin levels also showed significant improvement from the first month, indicating a prompt reduction in intravascular hemolysis. These changes likely reflect the immediate mechanical elimination of the high-shear forces responsible for red blood cell destruction, as well as the effective sealing of the PVL, which prevents further hemolysis. In transfusion-dependent patients, this favorable trajectory was even more pronounced: LDH and indirect bilirubin levels declined significantly from the first month, while Hb levels increased from the sixth month onward and remained elevated throughout follow-up. These findings suggest that effective PVL closure can gradually restore hematologic balance, particularly in patients who previously had severe hemolysis requiring chronic transfusions.

The need for blood transfusions declined markedly following TPVLC, likely as a result of the high technical success rate achieved in this cohort. This success can be attributed to the expertise of the interventional cardiologist and heart team, as well as the effective and precise deployment of the AVP III, which was the most frequently used occlusion device. The procedure led to a significant reduction in the incidence of moderate PVL, thereby minimizing the turbulent flow and shear stress responsible for ongoing red blood cell destruction. Only 3 patients met the criteria for persistent PVL-related hemolysis during follow-up, suggesting that most cases benefited from near-complete defect sealing.

Comparative analysis between patients undergoing PVL closure primarily for hemolysis vs those treated for heart failure revealed a significantly higher prevalence of mechanical prostheses and mitral valve involvement in the hemolysis group, suggesting a stronger mechanical component in red cell destruction. Μechanical valves can contribute to PVLs through improper placement, inadequate sealing, and increased pressure or altered blood flow. Over time, tissue weakening or fibrosis around the valve can exacerbate PVL, while trauma or inflammation of the surrounding heart tissue further increases the risk of leaks. In addition, patients in the hemolysis cohort demonstrated significantly lower Hb levels and higher markers of hemolysis (LDH and indirect bilirubin), consistent with ongoing red cell lysis. LVEF was also significantly reduced in this group, potentially reflecting chronic volume overload or subclinical myocardial dysfunction related to prolonged anemia. The higher prevalence of chronic kidney disease among hemolysis patients further suggests that systemic comorbidities may exacerbate hemolytic processes, either by impairing erythropoiesis or amplifying oxidative stress and inflammation. However, the overall survival remained limited, as demonstrated by Kaplan-Meier analysis, which revealed that cardiovascular and PVL-related mortality accounted for only a minority of deaths. PVL-related death was confined to the early postprocedural period, whereas most late deaths were attributable to extracardiac causes, highlighting the high burden of non-cardiac comorbidities in this population. These findings emphasize the need for precise procedural execution, thoughtful patient selection, and comprehensive long-term follow-up to optimize outcomes in this complex patient population.

Limitations

This multicenter study has several limitations. The small sample size of 39 patients reduces the statistical power and generalizability of the results. Variability across centers in terms of procedural techniques and patient selection could introduce biases. Additionally, the lack of a control group (eg, surgical repair or untreated cases) limits the ability to attribute outcomes solely to the transcatheter approach. Short follow-up may also underreport long-term complications. Moreover, although a standardized definition of hemolysis was retrospectively applied, uniform and objective transfusion criteria were not consistently implemented across centers. Despite the use of a standardized definition for hemolysis, transfusion decisions remained partly influenced by subjective clinical judgment. In addition, the assessment of PVL severity was based on semi-quantitative echocardiographic grading as per EACVI recommendations and performed by local imaging experts. Because of the retrospective and multicenter nature of the study, centralized core-lab adjudication was not feasible, potentially introducing interobserver variability. Furthermore, confounding factors like comorbidities and inconsistent baseline transfusion needs could complicate the interpretation of survival and hemolysis indices.

Conclusions

TPVLC in patients with hemolytic anemia led to an early and sustained improvement in hemolysis markers, including LDH, Hb, and indirect bilirubin. These benefits were evident as early as 1 month post-procedure and maintained through 24 months, both in the overall cohort and in the transfusion-dependent subgroup. The procedure was associated with a low incidence of post-closure hemolysis, and specific preprocedural factors—mechanical prostheses, mitral valve involvement, and chronic kidney disease—were linked to a higher likelihood of hemolysis.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Thekla Lytra, MD, MSc, PhD(c)1; Konstantinos Kalogeras, MD, PhD1; Vlasis Ninios, MD, MRCP2; Konstantinos Spargias, MD, PhD3; Petros Dardas, MD, PhD4; Manolis Vavuranakis, FESC, FACC, FSCAI1

From the 13rd Department of Cardiology, University of Athens, Sotiria Hospital, Athens, Greece; 2Cardiology Department, Interbalkan Medical Center, Thessaloniki, Greece; 3Cardiology Department, Hgeia Hospital, Athens, Greece; 4Cardiology Department, Aghios Loukas Hospital, Thessaloniki, Greece.

Disclosures: The authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Address for correspondence: Thekla Lytra, MD, MSc, PhD(c), 3rd Department of Cardiology, University of Athens, Sotiria Hospital, Athens 11527, Greece. Email: theklalytra@hotmail.com

References

- Desai A, Messenger JC, Quaife R, Carroll J. Update in paravalvular leak closure. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2021;23(9):122. doi:10.1007/s11886-021-01552-w

- Giblett JP, Rana BS, Shapiro LM, Calvert PA. Percutaneous management of paravalvular leaks. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16(5):275-285. doi:10.1038/s41569-018-0147-0

- Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(36):2739-2791. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx391

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(2):252-289. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.011

- Zoghbi WA, Chambers JB, Dumesnil JG, et al; American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee; Task Force on Prosthetic Valves; American College of Cardiology Cardiovascular Imaging Committee; Cardiac Imaging Committee of the American Heart Association; European Association of Echocardiography; European Society of Cardiology; Japanese Society of Echocardiography; Canadian Society of Echocardiography; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association; European Association of Echocardiography; European Society of Cardiology; Japanese Society of Echocardiography; Canadian Society of Echocardiography. Recommendations for evaluation of prosthetic valves with echocardiography and doppler ultrasound: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Task Force on Prosthetic Valves, developed in conjunction with the American College of Cardiology Cardiovascular Imaging Committee, Cardiac Imaging Committee of the American Heart Association, the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, the Japanese Society of Echocardiography and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography, endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association, European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, the Japanese Society of Echocardiography, and Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22(9):975-1014; quiz 1082-1084. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2009.07.013

- Hein R, Wunderlich N, Robertson G, Wilson N, Sievert H. Catheter closure of paravalvular leak. EuroIntervention. 2006;2(3):318-325.

- Pate GE, Al Zubaidi A, Chandavimol M, Thompson CR, Munt BI, Webb JG. Percutaneous closure of prosthetic paravalvular leaks: case series and review. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;68(4):528-533. doi:10.1002/ccd.20795

- Smolka G, Pysz P, Ochała A, et al. Transcatheter paravalvular leak closure and hemolysis—a prospective registry. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13(3):575-584. doi:10.5114/aoms.2016.60435

- Zamorano J, Gonçalves A, Lancellotti P, et al. EACVI reviewers. The use of imaging in new transcatheter interventions: an EACVI review paper. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17(8):835-835af. doi:10.1093/ehjci/jew043

- Ruiz CE, Hahn RT, Berrebi A, et al; Paravalvular Leak Academic Research Consortium. Clinical trial principles and endpoint definitions for paravalvular leaks in surgical prosthesis: an expert statement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(16):2067-2087. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.02.038

- Ruiz CE, Jelnin V, Kronzon I, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous closure of periprosthetic paravalvular leaks. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(21):2210-2217. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.074

- Kalogeras K, Ntalekou K, Aggeli K, et al. Transcatheter closure of paravalvular leak: multicenter experience and follow-up. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2021;62(5):416-422. doi:10.1016/j.hjc.2021.02.002

- García E, Arzamendi D, Jimenez-Quevedo P, et al. Outcomes and predictors of success and complications for paravalvular leak closure: an analysis of the SpanisH real-wOrld paravalvular LEaks closure (HOLE) registry. EuroIntervention. 2017;12(16):1962-1968. doi:10.4244/EIJ-D-16-00581

- Fanous EJ, Mukku RB, Dave P, et al. Paravalvular leak assessment: challenges in assessing severity and interventional approaches. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22(12):166. doi:10.1007/s11886-020-01418-7

- Vavuranakis M, Kalogeras K, Lozos V, et al. Transapical closure of multiple mitral paravalvular leaks with dual device deployment through a single sheath: a heart team job. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2018;59(6):367-369. doi:10.1016/j.hjc.2018.01.007

- Joseph TA, Lane CE, Fender EA, Zack CJ, Rihal CS. Catheter-based closure of aortic and mitral paravalvular leaks: existing techniques and new frontiers. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2018;15(9):653-663. doi:10.1080/17434440.2018.1514257

- Alkhouli M, Sarraf M, Maor E, et al. Techniques and outcomes of percutaneous aortic paravalvular leak closure. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9(23):2416-2426. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2016.08.038

- Jilaihawi H, Kashif M, Fontana G, et al. Cross-sectional computed tomographic assessment improves accuracy of aortic annular sizing for transcatheter aortic valve replacement and reduces the incidence of paravalvular aortic regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(14):1275-1286. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.045

- Goktekin O, Vatankulu MA, Ozhan H, et al. Early experience of percutaneous paravalvular leak closure using a novel Occlutech occluder. EuroIntervention. 2016;11(10):1195-1200. doi:10.4244/EIJV11I10A237

- Onorato EM, Muratori M, Smolka G, et al. Midterm procedural and clinical outcomes of percutaneous paravalvular leak closure with the Occlutech paravalvular leak device. EuroIntervention. 2020;15(14):1251-1259. doi:10.4244/EIJ-D-19-00517

- Calvert PA, Northridge DB, Malik IS, et al. Percutaneous device closure of paravalvular leak: combined experience from the United Kingdom and Ireland. Circulation. 2016;134(13):934-944. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022684

- Abuelatta R, Khedr L, AlHarbi I, Naeim HA. Management of severe haemolytic anaemia due to residual small mitral paravalvular leak post-percutaneous closure: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2020;4(3):1-6. doi:10.1093/ehjcr/ytaa101

- Hascoët S, Smolka G, Blanchard D, et al. Predictors of clinical success after transcatheter paravalvular leak closure: an international prospective multicenter registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15(10):e012193. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.122.012193

- Panaich SS, Maor E, Reddy G, et al. Effect of percutaneous paravalvular leak closure on hemolysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;93(4):713-719. doi:10.1002/ccd.27917

- Onorato EM, Alamanni F, Muratori M, et al. Safety, Efficacy and long-term outcomes of patients treated with the Occlutech paravalvular leak device for significant paravalvular regurgitation. J Clin Med. 2022;11(7):1978. doi:10.3390/jcm11071978

- Sorajja P, Cabalka AK, Hagler DJ, Rihal CS. Long-term follow-up of percutaneous repair of paravalvular prosthetic regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(21):2218-2224. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.07.041

- Bernard S, Yucel E. Paravalvular leaks—from diagnosis to management. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2019;21(12):67. doi:10.1007/s11936-019-0776-6

- Cruz-Gonzalez I, Ruiz CE, Hijazi ZM, Rama-Merchan JC. Transcatheter paravalvular leak closure: history, available devices. In: Smolka G, Wojakowski W, Tendera M, eds. Transcatheter Paravalvular Leak Closure. Springer Singapore; 2017:43-53. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-5400-6_3