Long-Term Outcomes After Transcatheter Tricuspid Valve-in-Valve Replacement

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Objectives. Transcatheter tricuspid valve-in-valve (ViV) replacement has emerged as a less invasive alternative to redo surgery in patients with failing bioprosthetic tricuspid valves. While short- and mid-term outcomes have been reported, data on long-term follow-up remain limited.

Methods. The authors conducted a single-center observational study including 12 consecutive patients who underwent transcatheter tricuspid ViV replacement. Clinical, echocardiographic, and procedural data were prospectively collected. Patients were followed at 1 and 12 months, and yearly thereafter; follow-up included annual clinical visits and echocardiography.

Results. The mean age of the patients was 45 years (range, 23-69 years); 92% were women, and the indication for ViV was prosthetic valve regurgitation in most (58%) cases. A balloon-expandable SAPIEN valve (Edwards Lifesciences) was implanted in all cases, with 100% procedural success. After a mean follow-up of 6 years (range, 1-11 years), 3 (25%) patients died, and 1 was readmitted because of heart failure. Functional status improved significantly, with all surviving patients in New York Heart Association class I or II at last follow-up. Transvalvular gradients remained stable over time in 83% of the patients. Two (17%) patients developed bioprosthetic valve dysfunction during follow-up: 1 due to significant tricuspid stenosis and the other due to severe tricuspid regurgitation.

Conclusions. Tricuspid ViV replacement offers durable symptomatic improvement and stable prosthesis function during long-term follow-up in most cases. This study is the first to report outcomes greater than or equal to 5 years in this population and supports the continued use of ViV as a viable option for these patients. Larger studies are warranted to validate these findings.

Introduction

Bioprosthetic valves are often preferred over mechanical prostheses in tricuspid replacement because of the lower risk of thromboembolic complications, as well as major bleeding associated with lifelong anticoagulation therapy.1 However, bioprosthetic valves are prone to structural valve degeneration, with reintervention rates at 10 years ranging between 10% and 20% in contemporary cohorts.2,3 Redo tricuspid valve surgery—whether after prior repair or replacement—carries considerable procedural risk, with reported early mortality rates of 10% to 15%.4-6 As a result, less invasive alternatives have gained increasing attention.

Transcatheter valve-in-valve (ViV) procedures have been well established in the aortic valve position,7 and ViV tricuspid interventions have also shown good early and midterm outcomes in both pediatric and adult populations.7-12 Despite these advances, data on long-term clinical outcomes following transcatheter tricuspid ViV replacement remain limited. This is of particular importance in the tricuspid space, as tricuspid ViV interventions are performed off-label using transcatheter valve systems dedicated to the treatment of aortic and pulmonary valves. Thus, the objective of this study was to determine the long-term clinical and hemodynamic outcomes of patients undergoing transcatheter ViV tricuspid procedures.

Methods

Patient population

The study population included 12 consecutive patients who were not candidates for reoperation and underwent transcatheter tricuspid ViV replacement at our center between October 2013 and March 2023. All patients were followed at 1 month after ViV replacement and then annually with a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) and clinical visit. No patient was lost to follow-up. Patient demographics, baseline characteristics, and periprocedural outcomes were collected prospectively in a dedicated database. The study was performed in accordance with the ethics committee of our institution, and all patients provided signed informed consent for the procedures.

Procedural technique

All ViV procedures were performed in a cath lab under fluoroscopic guidance using transfemoral venous access. Procedures were performed under local anesthesia and light sedation or under general anesthesia. A balloon-expandable transcatheter heart valve (SAPIEN XT or SAPIEN 3; Edwards Lifesciences) was advanced and deployed in the failed bioprosthesis without rapid ventricular pacing. Preexisting pacemaker leads crossing the tricuspid valve (if any) were jailed during the procedure. Hemostasis was achieved percutaneously, and all patients were monitored on a cardiac ward for at least 24 hours.

Study outcomes

Clinical outcomes included all-cause mortality and heart failure-related hospitalization over time. Other events—such as tricuspid valve reintervention, new pacemaker implantation, pacemaker complications related to jailed leads, bleeding, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, bioprosthetic valve thrombosis or dysfunction (defined as >1 grade worsening of tricuspid regurgitation [TR] or significant tricuspid stenosis with a mean gradient >10 mm Hg), and stroke—were also recorded. Functional status was assessed using the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification. Clinical events were defined according to the Tricuspid Valve Academic Research Consortium (TVARC) criteria.13 Echocardiographic data included mean transvalvular gradients and the presence and severity of TR reported at baseline, 30 days, 1 year, 2 to 4 years, and 5 to 10 years. Qualitative assessment of ventricular function and right ventricular (RV) dilatation were also performed.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as frequency (%), and continuous variables were reported as median (minimum to maximum or IQR) or mean (SD). Changes in the median transtricuspid prosthetic gradient over time were assessed using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test, and changes in functional class and tricuspid TR grade were compared using the Stuart-Maxwell test. Statistical significance was set at a P-value of less than 0.05. All analyses were performed using R (version 4.5.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing,) and GraphPad Prism (version 10.1.1).

Results

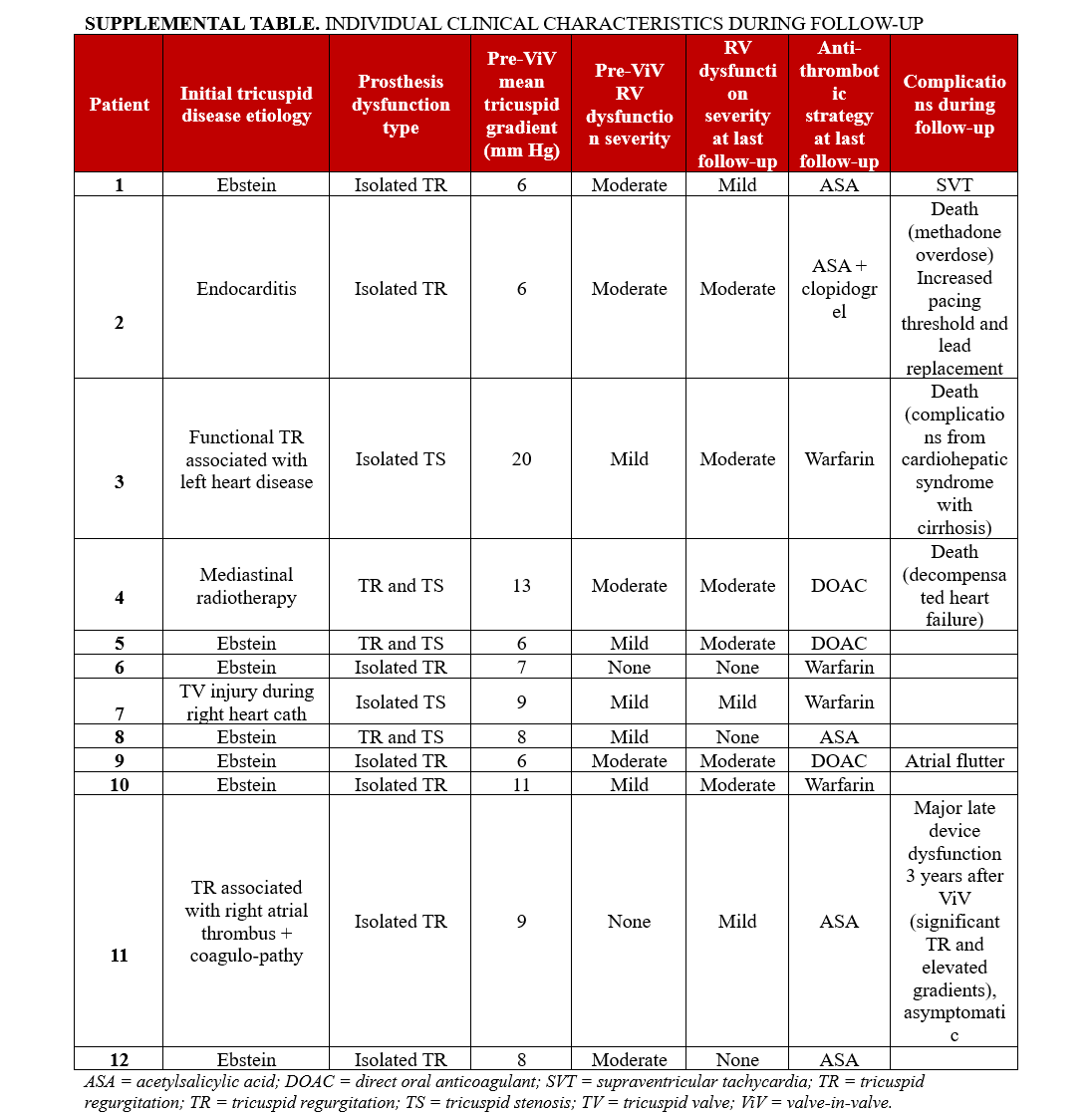

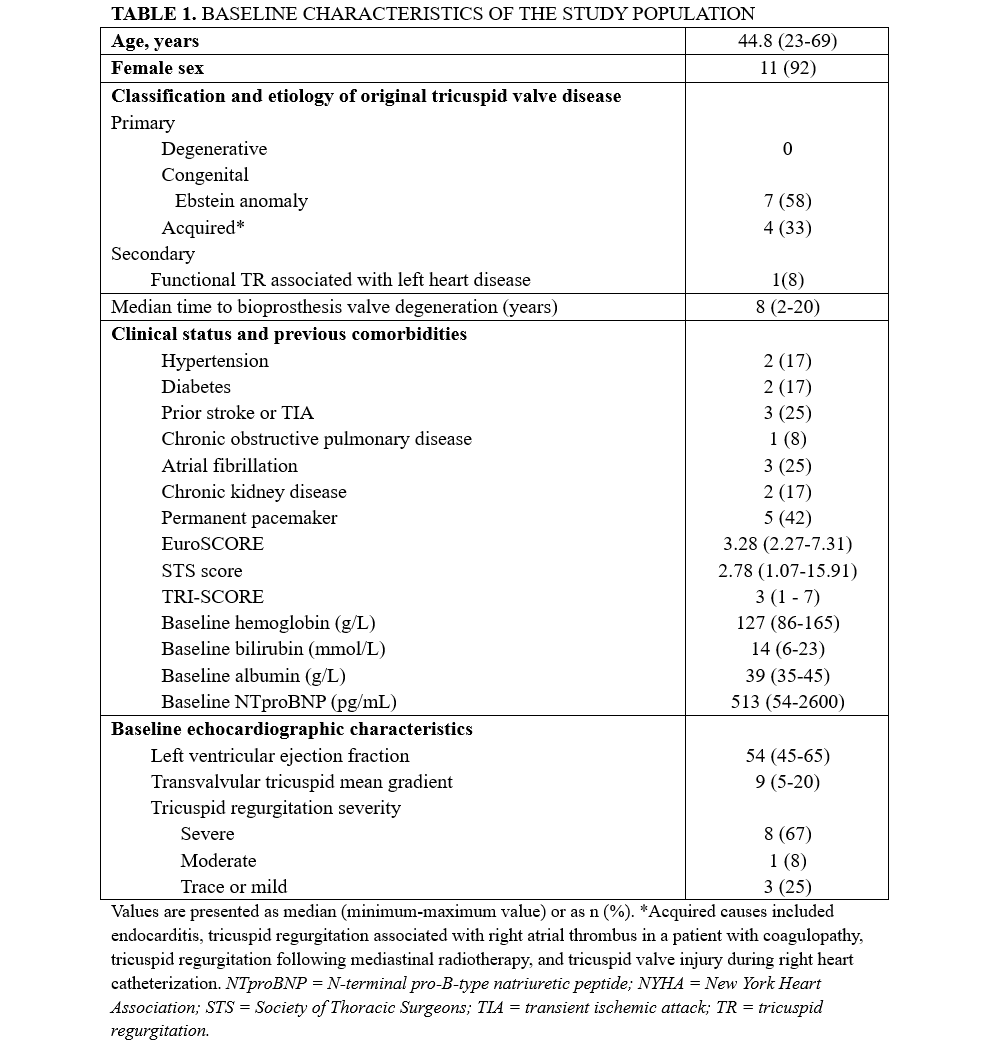

The main baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 45 ± 15 years, and most of them were women (n = 11, 92%). The principal cause of tricuspid valve disease was primary TR, distributed between congenital and acquired etiologies, with Ebstein anomaly accounting for 7 (58%) patients. Only 1 patient had secondary TR due to left ventricular disease. The median time from tricuspid valve surgery to prosthetic valve dysfunction was 8 years (range, 2-20 years). Four (33%) patients had other prosthetic valves in place. Comorbid conditions included atrial fibrillation (n = 3, 25%), chronic kidney disease (n = 2, 17%), and prior stroke or transient ischemic attack (n = 3, 25%). Five (42%) patients had permanent pacemakers: 3 with dual-chamber intravascular leads and 2 with dual-chamber epicardial leads. The median score baselines of the TRI-SCORE, EuroSCORE, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) scores were 3 (range, 1-7), 3.28 (range, 2.27-7.31), and 2.78 (range, 1.07-15.91), respectively. The indications for reintervention were isolated regurgitation in 7 (58%) patients, isolated stenosis in 2 (17%), and combined regurgitation and stenosis in 3 (25%). Additional individual patient characteristics are provided in the Supplemental Table.

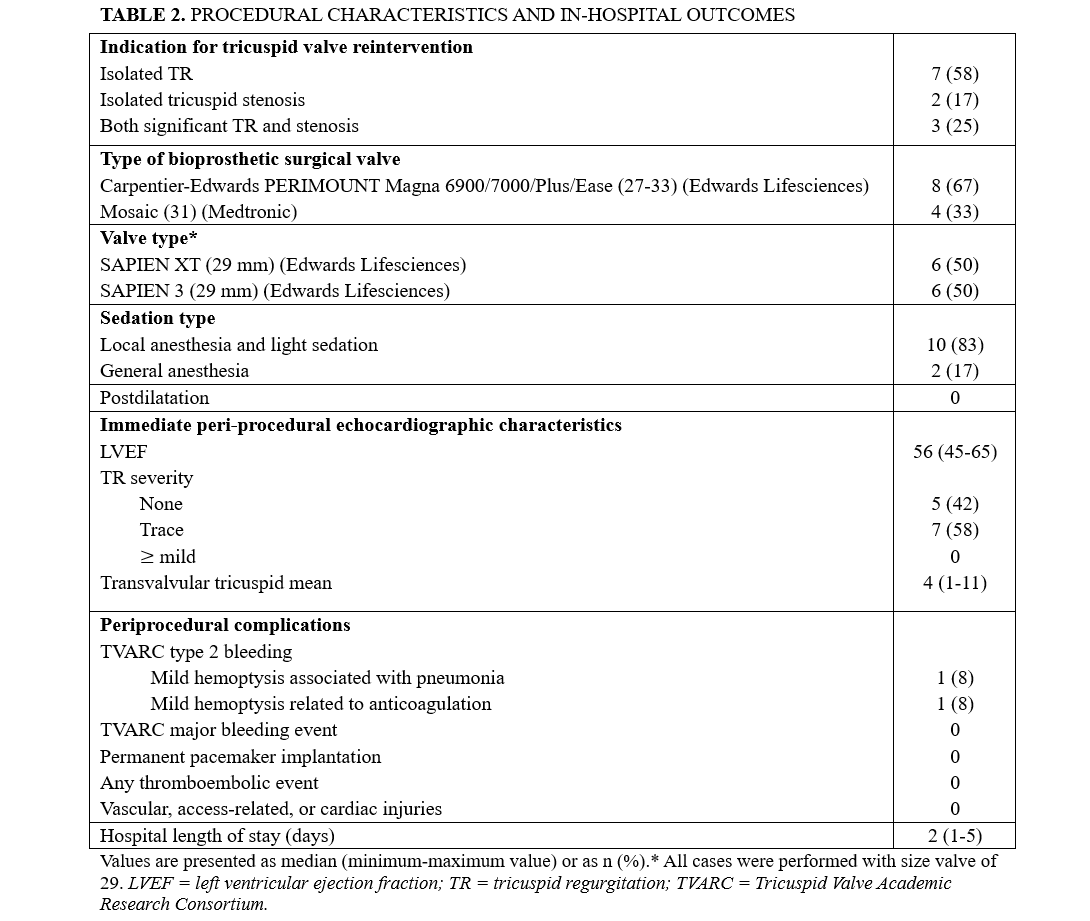

Procedural characteristics and outcomes

The main procedural characteristics and in-hospital outcomes are presented in Table 2. The most frequently degenerated surgical bioprosthesis was the Carpentier-Edwards PERIMOUNT (Edwards Lifesciences) (n = 8, 67%), whereas all ViV procedures were performed using a SAPIEN XT or SAPIEN 3 transcatheter heart valve (Edwards Lifesciences). All procedures were successful, and the median length of hospital stay after the procedure was 2 days (range, 1-5 days). No vascular, access-related, or cardiac injuries occurred during or after the procedure. Postprocedural echocardiography showed no or trace residual TR in any of the patients and a mean transvalvular gradient of 5.6 ± 2.4 mm Hg.

Clinical outcomes and follow-up

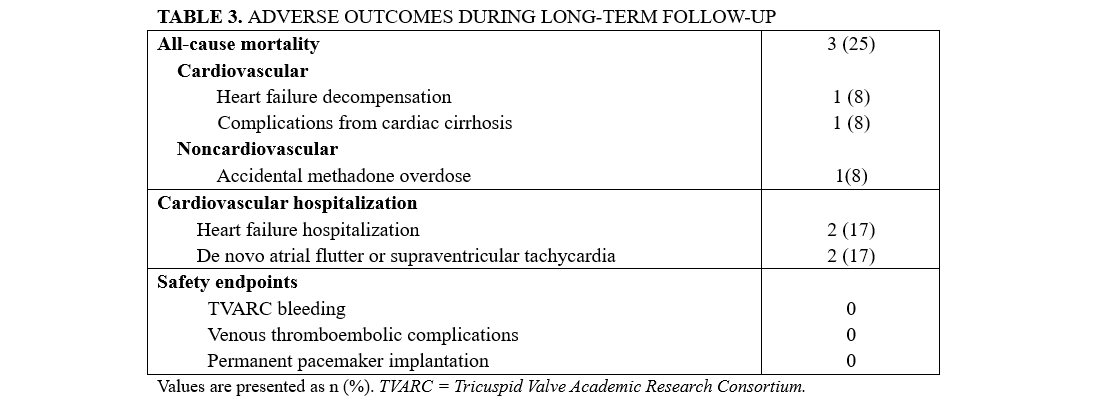

The mean follow-up of the study population was 6 years (range, 1-11 years), and no patients were lost to follow-up. The clinical outcomes are summarized in Table 3. Three (25%) patients died during the follow-up period. There were 2 cardiovascular deaths: 1 at 11 months post-procedure due to complications of cardiac cirrhosis, and another at 30 months from decompensated heart failure. A third, non-cardiovascular death occurred at 38 months, secondary to an accidental methadone overdose at home. Four cardiovascular hospitalizations occurred during follow-up: 2 for heart failure, 2 for cardiac arrhythmias (1 de novo atrial flutter and 1 supraventricular tachycardia).

Two patients developed bioprosthetic valve dysfunction, classified as major late device dysfunction according to TVARC. The first case involved severe TR with an elevated mean gradient 3 years after the procedure; however, the patient remained in good functional class, and no reintervention was planned at the last follow-up. The second case was a patient who later died from methadone overdose. This patient developed significant tricuspid stenosis (mean gradient >10 mm Hg) at 14 months and was maintained on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) during follow-up. No reintervention was planned, likely because the patient’s symptoms remained stable.

Echocardiographic findings

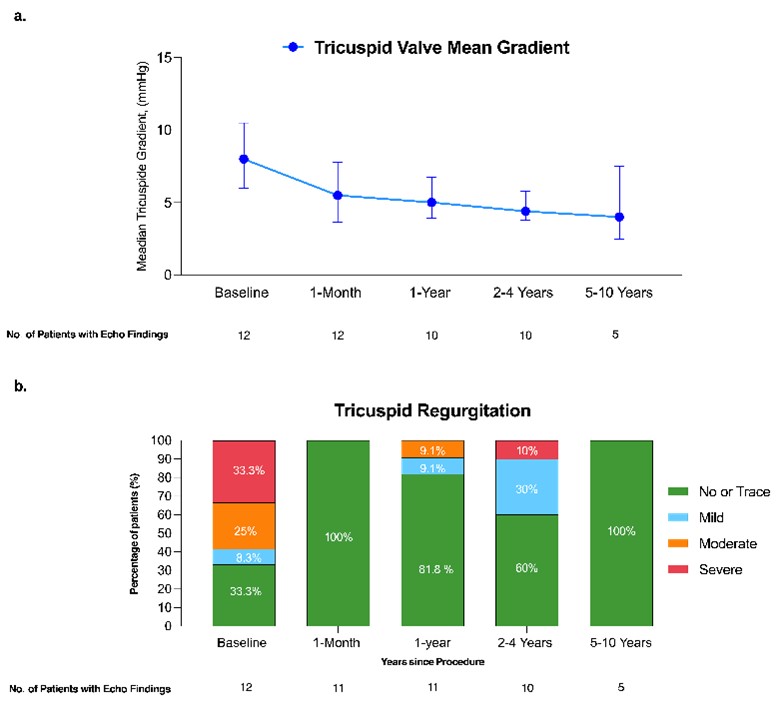

Mean transvalvular gradients declined significantly after ViV replacement and remained stable throughout follow-up (Figure 1A). The mean transvalvular gradient decreased from 9.2 ± 4.1 mm Hg at baseline to 4.0 ± 2.6 mm Hg at discharge (P = .002). It increased slightly at 1 month (5.6 ± 2.4 mm Hg) but remained significantly lower than baseline (P = .01). This difference persisted at the last follow-up (5.9 ± 3.4 mm Hg; P = .03) compared to baseline, indicating sustained valve performance in most patients.

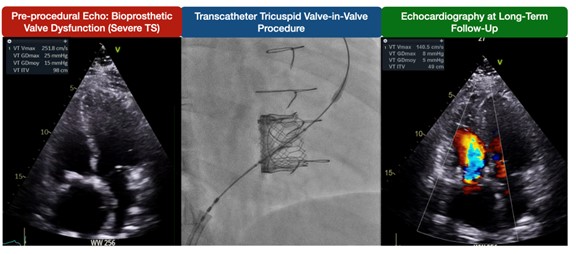

Data on TR severity during follow-up are shown in Figure 1B. At baseline, 33.3% (4) of patients had severe TR, 25% (3) had moderate TR, 8.3% (1) had mild TR, and 33.3% (4) had no or trace TR. At 1 month, all patients had no or trace TR (P = .04). During follow-up, 1 patient developed severe TR at the third year, classified as device dysfunction according to TVARC. However, this patient remained in NYHA class II and did not undergo tricuspid reintervention at the last follow-up. Figure 2 illustrates a case with sustained gradient improvement and no residual TR.

Echocardiographic assessments of RV function and size were available for all 12 patients at baseline and for all surviving patients during follow-up. At the time of ViV replacement, RV dysfunction was common, with only 2 (16.6%) patients exhibiting normal function. Mild and moderate dysfunction were each observed in 41.7% (5) of patients. At the last follow-up, 40% (4) of surviving patients exhibited normal function, 30% (3) mild dysfunction, and 30% (3) moderate dysfunction. At the time of the procedure, RV size was normal in 50% (6) of the patients, while 16.6% (2) had mild dilatation and 33.3% (4) had moderate dilatation. This pattern persisted at the last follow-up, with 40% (4) of patients having normal RV size and 10% (1) presenting with severe dilatation.

Functional class and quality of life

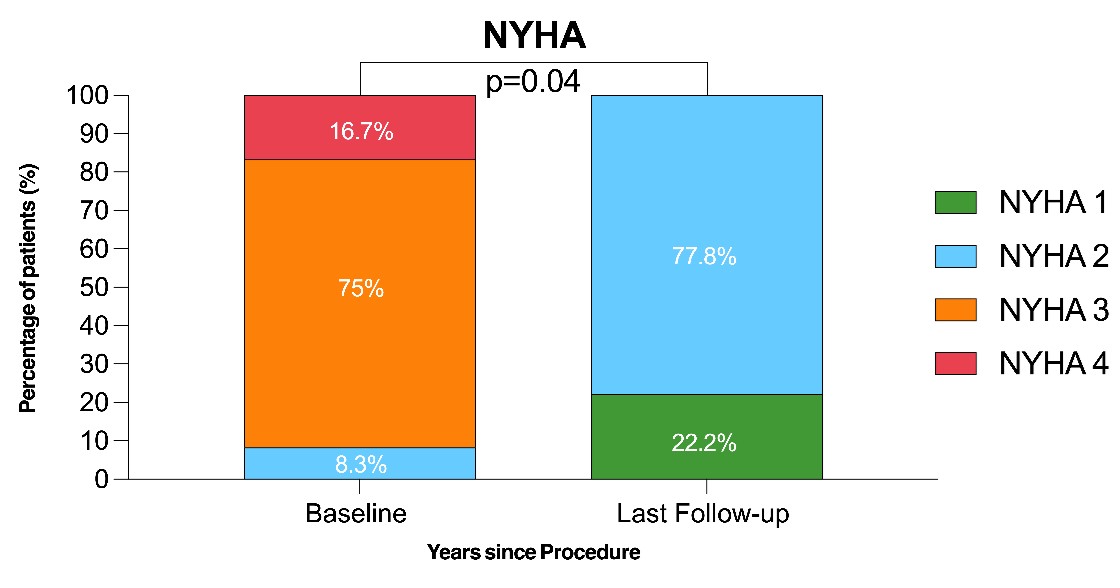

Data on NYHA functional class were available in all patients at baseline and all surviving patients at each follow-up interval. At the time of the procedure, most patients were in NYHA class III (9, 75%) or IV (2, 16.7%), with only 1 (8.3%) patient in class II. At the last follow-up among the surviving patients, the NYHA class had improved significantly (P = .04) (Figure 3). Data on Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)-23 scores assessing quality of life were available only at the last follow-up and showed a median score of 75 (range, 68-92 years) among the 9 surviving patients, corresponding to a “good to excellent” self-reported quality of life.

Antithrombotic management and bleeding events

Antithrombotic strategy varied considerably across the study population and is summarized in Table 4. Excluding patients who were already receiving anticoagulation for preexisting indications—such as atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, antiphospholipid syndrome, or mechanical valve prostheses—different strategies were employed. Three patients received a 3-month course of either dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) or warfarin, while 2 patients remained on DAPT and 1 patient on warfarin long term. One patient switched from aspirin to apixaban 5 years after ViV replacement because of a subclinical increase in the mean transvalvular gradient from 4 to 6 mm Hg. Given the presence of moderate right ventricular dysfunction, this adjustment was made to reduce the risk of valve thrombosis, after which the gradient returned to the baseline. Two bleeding events, consisting of mild hemoptysis associated with pneumonia and mild hemoptysis related to anticoagulation, were reported after the procedure and classified as TVARC type 2 bleeding. No other episode of bleeding was documented during the follow-up.

Patients with jailed pacemaker leads

Among the 3 patients with intravascular pacemakers and jailed leads, no acute lead dislodgment or fracture was reported during or after the procedure. However, 2 patients showed increased pacing thresholds because of ventricular lead entrapment during follow-up. In the first patient, the pacing threshold increased from 1 V at baseline to 2.25 V at 1-year follow-up, requiring placement of a new transvenous lead and battery replacement. The old lead was left in place without extraction. In the second patient, the threshold rose from 0.75 V at baseline to 1.5 V at 30 days, further increasing to 1.75 V at 1 year and reaching 2.25 V at 2 years. Lead replacement and battery change were indicated; however, the procedure could not be performed because of progressive heart failure decompensation, which ultimately resulted in the patient’s death.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on tricuspid ViV replacement to report outcomes beyond 5 years. The main findings can be summarized as follows: (1) the tricuspid ViV population represents a relatively young cohort (median age of 45 years) in whom long-term follow-up is crucial; (2) intraprocedural and clinical success rates were very high, with improved hemodynamic and functional status that was maintained in most patients over time (up to 10 years); (3) cardiovascular mortality and heart failure rehospitalization accounted for about one-fourth of the patients after a median follow-up of 6 years; and (4) although not all patients received anticoagulation during follow-up, no cases of bioprosthetic valve thrombosis were documented, while bioprosthetic valve dysfunction was observed in 17% of cases.

All-cause mortality in our cohort was higher (25%) than in larger series of tricuspid ViV procedures, which have reported mortality rates of 5% to 12%. However, these cohorts had much shorter follow-up durations (median, 13-15.3 months), and most reported deaths occurring within the first year.9,12 Notably, our findings are comparable to those of smaller studies reporting mid-term outcomes (mean follow-up of 3 years and mortality rates between 17% and 33%).14,15 These differences may reflect the extended observation period of our study and underscores the importance of long-term surveillance. Two patients in our cohort died from cardiovascular causes: 1 from heart failure secondary to chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity, and the other from heart failure complicated by cardiohepatic syndrome, which resulted in cirrhosis with multiple terminal complications. Similarly to all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality was also higher than rates reported in other cohorts (2.4%-6.5%). However, the incomplete follow-up of surviving patients in previous series limits the ability to make a direct comparison.9,12 Two patients (16.5%) were hospitalized for heart failure during follow-up. This rate is slightly higher than that reported in the current transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement trial (9.5%); however, their follow-up duration was only 1 year.16

Prosthetic valve hemodynamics remained stable throughout follow-up, with only 2 cases of prosthetic valve dysfunction due to severe TR and significant tricuspid stenosis. At the latest follow-up, an increased proportion of patients exhibited RV dysfunction; however, interpretation of this trend is limited by the small number of patients with available RV function data and subjective evaluation. These findings are consistent with those reported by McElhinney et al, who evaluated mid-term outcomes in a multicenter cohort of 306 patients undergoing tricuspid ViV or valve-in-ring replacement.9 In that study, prosthetic valve dysfunction during follow-up was observed in only 4.6% of patients and mean transvalvular gradients at final follow-up remained between 4 and 5 mm Hg. This closely mirrors the hemodynamic stability observed in our cohort, where the mean gradient remained near 5 mm Hg beyond the second year of follow-up. These values are consistent with current thresholds for normal Doppler flow parameters after tricuspid valve replacement.17 In contrast, the 2 patients in our cohort with bioprosthetic valve dysfunction demonstrated a marked elevation in the mean gradient (>10 mm Hg). This cutoff was chosen based on prior studies of tricuspid ViV procedures,9 rather than TVARC definitions, which primarily apply to outcomes of native TR treated with percutaneous devices.13 Moreover, although the presence of RV leads may confer a potential risk of immediate lead damage or dislodgement,18 no cases of this complication were observed.

Of note, the early improvements in functional status observed in our cohort were maintained over time. At baseline, the vast majority (>90%) of patients were in NYHA functional class III or IV, whereas all surviving patients were classified as NYHA I or II at follow-up. At last follow-up, KCCQ-23 scores reflected patient-reported quality of life in the “good to excellent” range, aligning well with their NYHA functional class and supporting the clinical relevance of these findings. Furthermore, to our knowledge, this is the first study to report an extended follow-up assessment of clinical success—measured by improvement from baseline in symptoms (NYHA class) as defined by the TVARC—for this type of procedure,13 supporting a sustained long-term benefit of tricuspid ViV replacement.

As previously described, antithrombotic management of patients undergoing ViV tricuspid replacement varied greatly in our population. This heterogeneity in management reflects the lack of evidence-based recommendations in the current literature regarding the optimal antithrombotic strategy in such patients.19 Current guidelines recommend the use of vitamin K antagonists for at least 3 months following bioprosthetic valve replacement in the tricuspid position, a strategy considered favorable in a low-pressure system.20 Similarly, the approved transcatheter tricuspid valve EVOQUE system recommends vitamin K antagonists or other anticoagulation therapy combined with aspirin during the first 6 months after implantation.16 Notably, in our cohort, although not all patients received routine short- or long-term anticoagulation after the procedure, only 1 had modification of antithrombotic therapy, likely reflecting concerns about valve thrombosis and durability. These findings highlight the importance of extended follow-up, as the low-pressure system may theoretically increase the risk of thrombotic events and compromise valve durability. Therefore, further research is essential to establish the optimal antithrombotic regimen in this setting.

Regarding jailed pacemaker leads, Anderson et al reported the incidence and types of pacemaker lead complications after transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement (TTVR), documenting 3 complications in 28 (10.7%) patients during a mean follow-up of 15.3 months: acute lead dislodgment, a marked increase in pacing impedance and threshold 2 weeks after TTVR, and lead fracture 7 months postprocedure.21 Although we did not observe lead dislodgment or complete fractures, we documented 2 cases out of 3 jailed ventricular leads with a clinically significant increase in pacing thresholds. In the first case, the increase occurred at 1 year and required lead replacement at 11 months postprocedure. In the second case, the pacing threshold progressively increased over 2 years; however, the patient died from heart failure decompensation before lead replacement could be performed. The remaining patient with jailed ventricular lead maintained normal device function after the procedure but died within the first year of follow-up from cardiac cirrhosis, limiting the ability to confirm lead integrity over time. A recent multidisciplinary consensus has emphasized the need to address long-term concerns, such as lead failure and the potential inability to perform transvenous lead extraction (TLE) when required in patients with jailed leads. Thus, lead extraction and other pacing strategies (coronary sinus pacing, leadless pacing) should be considered in a heart team approach in patients with a low to intermediate risk for TLE, pacing dependency, high risk of infective endocarditis, or an implantable cardioverter defibrillator.22

Limitations

This study has several limitations, including the small sample size and the retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data, which may reduce the strength of the conclusions and limit the ability to perform robust statistical comparisons. Additionally, as a single-center experience from a high-volume institution with substantial expertise in percutaneous structural interventions, its external validity may be limited. RV function was assessed qualitatively using TTE reports categorized as normal, mild, moderate, or severely impaired. Quantitative assessment of RV dysfunction was inconsistent, largely because commonly used parameters—such as tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion and tricuspid annular peak systolic velocity—are less reliable in the presence of tricuspid prosthetic valves, and other measures, including fractional area change, RV strain, and 3-dimensional RV evaluation, had not yet been routinely implemented during the study period. Nevertheless, long-term follow-up studies of surgical prostheses in the tricuspid position have also relied on qualitative RV assessment.23 Finally, the KCCQ-23 scores at the last follow-up could not be compared with the pre-intervention values, as baseline data were not collected.

Conclusions

This study is the first to report long-term follow-up in patients undergoing transcatheter tricuspid ViV replacement for bioprosthetic failure, with acceptable rates of cardiovascular mortality and hospitalization for heart failure. Improvements in the mean transvalvular gradients and NYHA functional class were sustained throughout the follow-up period. Larger studies with extended follow-up are warranted to assess antithrombotic management and clarify the relationship between valve durability and thromboembolic or bleeding events.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Émile Voisine, MD; Juan Hernando del Portillo, MD; Laurent Desjardins, MD; Christine Houde, MD; Jean Perron, MD; Frédéric Jacques, MD; Philippe Chetaille, MD; François Philippon, MD; Émilie Laflamme, MD; Élisabeth Bédard, MD; Josep Rodés-Cabau, MD, PhD

From the Quebec Heart and Lung Institute, Laval University, Quebec City, QC, Canada.

Dr Voisine and Dr del Portillo contributed equally to this work.

Acknowledgments: Dr Rodés-Cabau holds the Research Chair "Fondation Famille Jacques Larivière" for the Development of Structural Heart Interventions (Laval University, Quebec City, Canada).

Disclosures: Dr Rodés-Cabau has received institutional research grants and speaker fees from Edwards Lifesciences. The remaining authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Address for correspondence: Josep Rodés-Cabau, MD, PhD, Institut Universitaire de Cardiologie et de Pneumologie de Québec, 2725 Chemin Ste-Foy, Québec, QC G1V 4G5, Canada. Email: josep.rodes@criucpq.ulaval.ca

References

1. Anselmi A, Ruggieri VG, Harmouche M, et al. Appraisal of long-term outcomes of tricuspid valve replacement in the current perspective. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(3):863-871. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.09.081

2. Kang Y, Hwang HY, Sohn SH, Choi JW, Kim KH, Kim KB. Fifteen-year outcomes after bioprosthetic and mechanical tricuspid valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110(5):1564-1571. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.02.040

3. Sohn SH, Kang Y, Kim JS, Hwang HY, Kim KH, Choi JW. Early and long-term outcomes of bioprosthetic versus mechanical tricuspid valve replacement: a nationwide population-based study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2024;167(6):2117-2128.e11. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2023.01.025

4. Vassileva CM, Shabosky J, Boley T, Markwell S, Hazelrigg S. Tricuspid valve surgery: the past 10 years from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143(5):1043-1049. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.07.004

5. Jeganathan R, Armstrong S, Al-Alao B, David T. The risk and outcomes of reoperative tricuspid valve surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95(1):119-124. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.08.058

6. Sorajja P, Whisenant B, Hamid N, et al; TRILUMINATE Pivotal Investigators. Transcatheter repair for patients with tricuspid regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(20):1833-1842. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2300525

7. Cullen MW, Cabalka AK, Alli OO, et al. Transvenous, antegrade Melody valve-in-valve implantation for bioprosthetic mitral and tricuspid valve dysfunction: a case series in children and adults. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6(6):598-605. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2013.02.010

8. Ruparelia N, Mangieri A, Ancona M, et al. Percutaneous transcatheter treatment for tricuspid bioprosthesis failure. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;88(6):994-1001. doi:10.1002/ccd.26584

9. McElhinney DB, Aboulhosn JA, Dvir D, et al; VIVID Registry. Mid-term valve-related outcomes after transcatheter tricuspid valve-in-valve or valve-in-ring replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(2):148-157. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.051

10. McElhinney DB, Cabalka AK, Aboulhosn JA, et al; Valve-in-Valve International Database (VIVID) Registry. Transcatheter tricuspid valve-in-valve implantation for the treatment of dysfunctional surgical bioprosthetic valves: an international, multicenter registry study. Circulation. 2016;133(16):1582-1593. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019353

11. Aboulhosn J, Cabalka AK, Levi DS, et al. Transcatheter valve-in-ring implantation for the treatment of residual or recurrent tricuspid valve dysfunction after prior surgical repair. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(1):53-63. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2016.10.036

12. Taggart NW, Cabalka AK, Eicken A, et al. Outcomes of transcatheter tricuspid valve-in-valve implantation in patients with Ebstein anomaly. Am J Cardiol. 2018;121(2):262-268. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.10.017

13. Hahn RT, Lawlor MK, Davidson CJ, et al; TVARC Steering Committee. Tricuspid Valve Academic Research Consortium definitions for tricuspid regurgitation and trial endpoints. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82(17):1711-1735. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.08.008

14. Sahebjam M, Haji Zeinali A, Abbasi K, Borjian S. Mid to long-term echocardiographic follow-up of patients undergoing transcatheter tricuspid valve-in-valve replacement for degenerated bioprosthetic valves: first single-center report from Iran. J Tehran Heart Cent. 2022;17(3):112-118. doi:10.18502/jthc.v17i3.10843

15. Schamroth Pravda N, Vaknin Assa H, Levi A, et al. Tricuspid structural valve deterioration treated with a transcatheter valve-in-valve implantation: a single-center prospective registry. J Clin Med. 2022;11(9):2667. doi:10.3390/jcm11092667

16. Hahn RT, Makkar R, Thourani VH, et al; TRISCEND II Trial Investigators. Transcatheter valve replacement in severe tricuspid regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(2):115-126. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2401918

17. Praz F, George I, Kodali S, et al. Transcatheter tricuspid valve-in-valve intervention for degenerative bioprosthetic tricuspid valve disease. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2018;31(4):491-504. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2017.06.014

18. Davidson LJ, Tang GHL, Ho EC, et al; American Heart Association Interventional Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. The tricuspid valve: a review of pathology, imaging, and current treatment options: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149(22):e1223-e1238. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001232

19. Guedeney P, Rodés-Cabau J, Ten Berg JM, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for transcatheter structural heart intervention. EuroIntervention. 2024;20(16):972-986. doi:10.4244/EIJ-D-23-01084

20. Coisne A, Lancellotti P, Habib G, et al; EuroValve Consortium. ACC/AHA and ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart diseases: JACC guideline comparison. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82(8):721-734. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.05.061

21. Anderson JH, McElhinney DB, Aboulhosn J, et al; VIVID Registry. Management and outcomes of transvenous pacing leads in patients undergoing transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13(17):2012-2020. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2020.04.054

22. Fischer Q, Ellenbogen KA, Mittal S, et al. Atrioventricular conduction disturbances in patients undergoing transcatheter tricuspid valve intervention: a multidisciplinary consensus. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;18(14):1721-1736. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2025.06.026

23. Patlolla SH, Saran N, Schaff HV, et al. Prosthesis choice for tricuspid valve replacement: comparison of clinical and echocardiographic outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2024;167(2):668-679.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2022.07.003