Incidence, Correlates, and Outcomes of Echocardiographic Smoke-Like Effect After Transcatheter Edge-to-Edge Repair of Mitral Regurgitation With the MitraClip Device

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Objectives. The smoke-like effect (SE), the spontaneous echocardiographic contrast in the left atrium at transesophageal echocardiography, has been anecdotally reported after transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER) for mitral regurgitation (MR), but uncertainty persists on its impact. Thus, the authors aimed at appraising the incidence, correlates, and outcomes of SE after TEER.

Methods. The authors conducted a retrospective multicenter observational study that included all patients in whom successful TEER with MitraClip (Abbott) had been completed. SE was defined as the presence of swirling spontaneous echocardiographic contrast in the left atrium. Baseline clinical characteristics, echocardiographic features, and procedural details were collected. Outcomes included death, reintervention, and rehospitalization for heart failure (HF).

Results. A total of 2228 patients were included, with 143 (6.4%) exhibiting SE. Several baseline differences disfavored these individuals, including age, functional class, surgical risk, and significant tricuspid regurgitation (all P < .05). Procedurally, SE was associated with implantation of multiple MitraClips and longer procedures, but lower rates of significant residual MR (all P < .05). Hospital outcomes were similarly favorable and the same held true for subsequent follow-up (average 19 months, all P > .05). The only exception was the risk of rehospitalization for HF, which appeared marginally significant disfavoring the SE group at unadjusted analysis (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.68 [95% CI, 1.04-2.70], P = .033). This association was, however, no longer significant when baseline differences were taken into account (HR = 1.52 [95% CI, 0.94-2.48], P = .091).

Conclusions. SE after TEER is not uncommon, and is typically associated with a significantly worse clinical profile, particularly prior atrial fibrillation. Irrespectively, SE is not associated with adverse outcomes in the short- or long-term. Accordingly, it should not be considered per se as an indication for more aggressive medical management, with antithrombotic regimens being instead informed by other more established indications.

Introduction

Transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER) has revolutionized the management of mitral regurgitation (MR), offering a less invasive alternative to surgical repair, particularly for high-risk patients who may not be suitable for open-heart surgery.1-3 Despite its widespread adoption and proven efficacy, certain procedural outcomes, such as the development of the smoke-like effect (SE) or spontaneous echocardiographic contrast, remain underexplored.4 Notably, SE is characterized by swirling, smoke-like echoes in the left atrium observed during transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) or transthoracic echocardiography (TTE). This finding can be seen in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), mitral stenosis, or other cardiac abnormalities and may be associated with hypercoagulable conditions and increased thromboembolic risk.5-10

However, the occurrence of SE in patients undergoing TEER remains controversial, with some small reports suggesting an association with favorable procedural outcomes, such as optimal reduction in MR, and others indicating potential risks, such as prothrombosis or increased rehospitalization rates for heart failure (HF).11-13 This dichotomy underscores the importance of further investigation to clarify the role of SE in post-TEER patients.

The authors aim to fill this knowledge gap by systematically analyzing the incidence, correlates, and outcomes of SE in a large cohort of patients undergoing TEER with the MitraClip device (Abbott). By leveraging multicenter data and robust statistical analyses, we seek to provide comprehensive insights into the clinical implications of SE, guiding future therapeutic strategies and improving patient care in this complex and evolving field.

Methods

This work is an analysis of an ongoing prospective Italian multicenter observational study including patients undergoing TEER with the MitraClip device, which began enrolling patients in January 2016. The GIOTTO (GIse registry Of Transcatheter treatment of mitral valve regurgitaTiOn) study, which has been sponsored over several years by the Italian Society of Invasive Cardiology (GISE – Società Italiana di Cardiologia Interventistica, Milan, Italy) and was registered online in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03521921), has already provided several seminal reports.14-19 Ethical approval was obtained from all participating institutions, and all patients provided written informed consent.

The primary focus of the present analysis was to assess the incidence, correlates, and outcomes of SE, defined as the presence of swirling spontaneous echocardiographic contrast in the left atrium, detected via TEE after TEER.11-13,20-23 Given the study design and the scope of our work, SE was not graded, but simply reported in the case report form as present or absent, in keeping with currently recommended criteria.11 In addition, imaging tests were not repeated by the same or other operators, neither online nor offline, and thus we cannot elaborate precisely on inter- or intra-operatory agreement for SE assessment.

Several baseline clinical characteristics, echocardiographic features, and procedural details were systematically collected using a standardized electronic case report form maintained by Air-Tel, Milan, Italy. Baseline variables included demographic data, comorbidities, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, prior cardiac procedures, and medication history. Assessed echocardiographic parameters included the left atrial diameter, left ventricular dimensions, mitral valve gradient, and severity of tricuspid regurgitation. Procedural variables of interest included the number and generation of MitraClip devices implanted, fluoroscopy time, device time, and immediate success.

The primary outcomes of interest included death, cardiac death, reintervention, rehospitalization, and rehospitalization for HF. Both in-hospital and follow-up outcomes were evaluated. Follow-up data were collected through scheduled visits and telephone interviews, ensuring comprehensive data capture for survival analysis and rehospitalization events.

Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables, with means and SDs for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Comparisons between patients with and without SE were performed using unpaired Student t test for continuous variables and Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was utilized to assess the time-to-event outcomes, with the Tarone-Ware test used for comparing survival curves. Unadjusted and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were employed to better appraise the face value as well as the independent prognostic role of SE. Statistical significance was set at a 2-tailed P-value of 0.05, and all analyses were conducted using Python 3.11 (Python Software Foundation) and Stata 13 (StataCorp).

Results

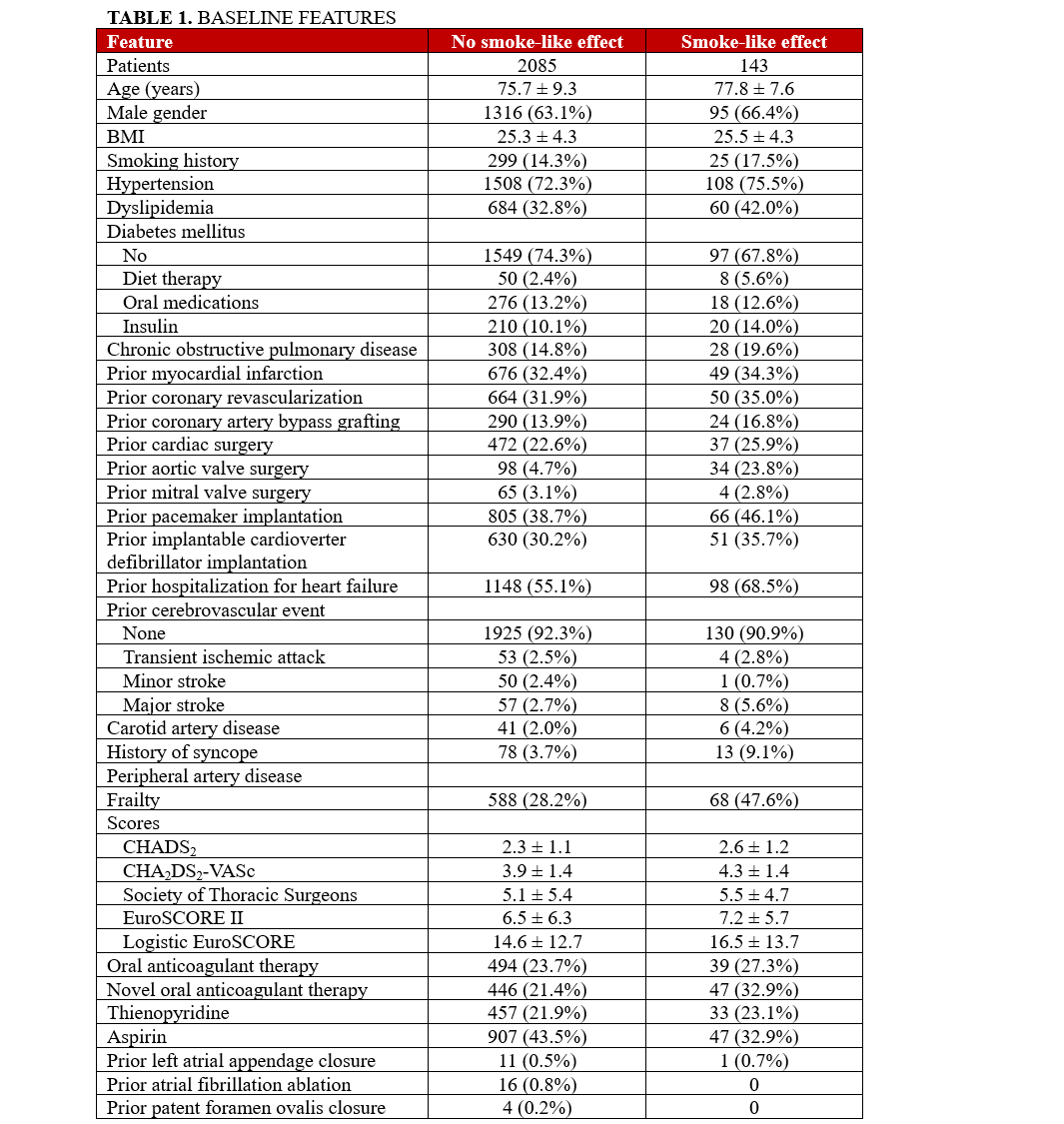

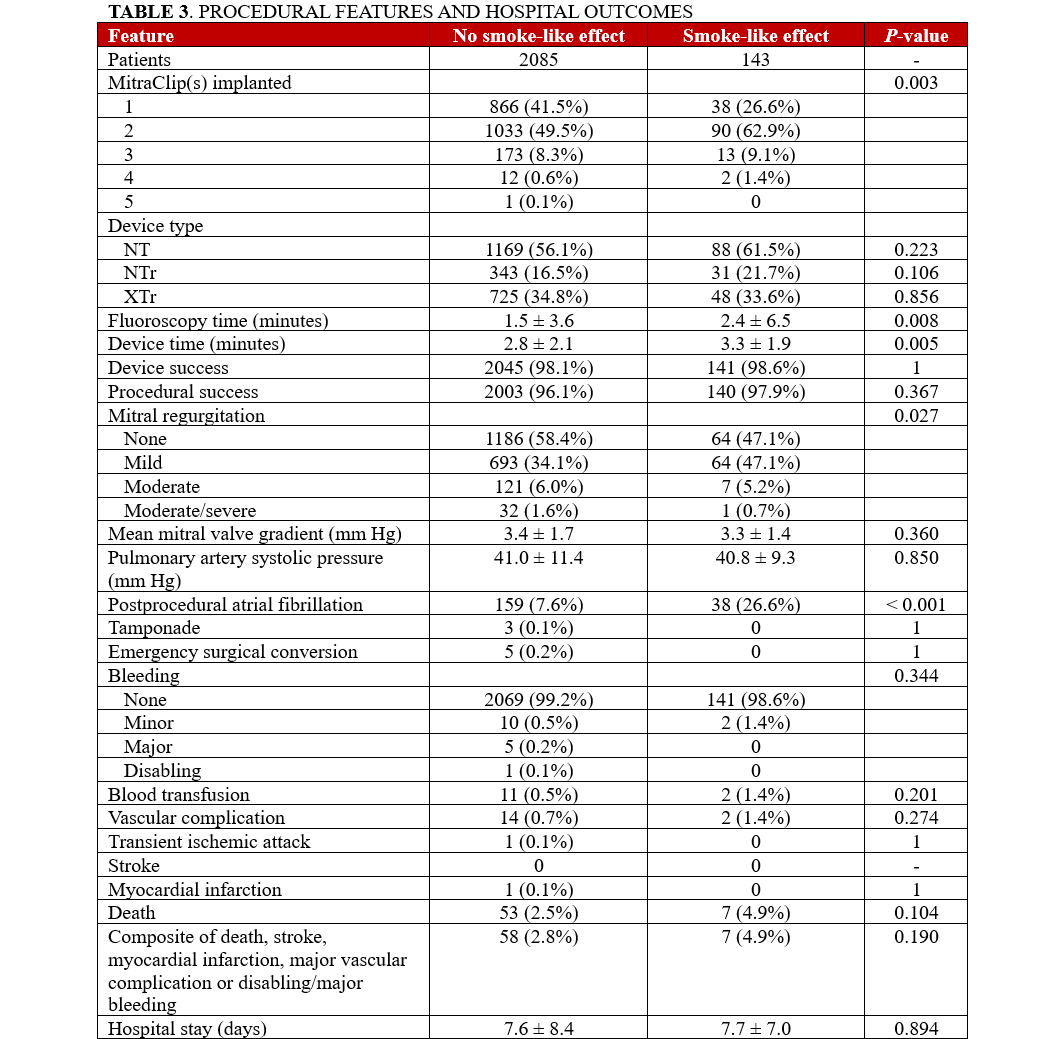

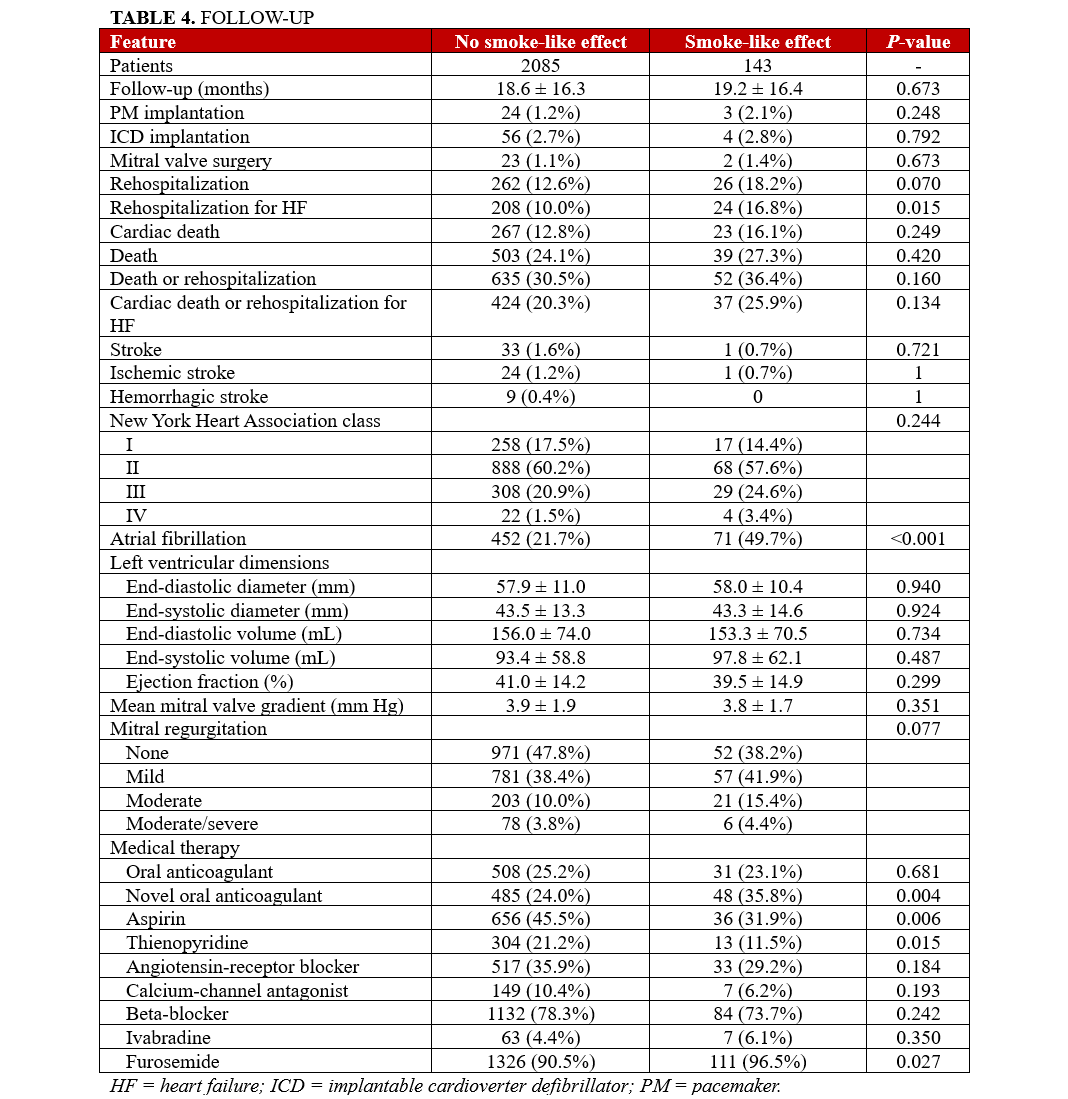

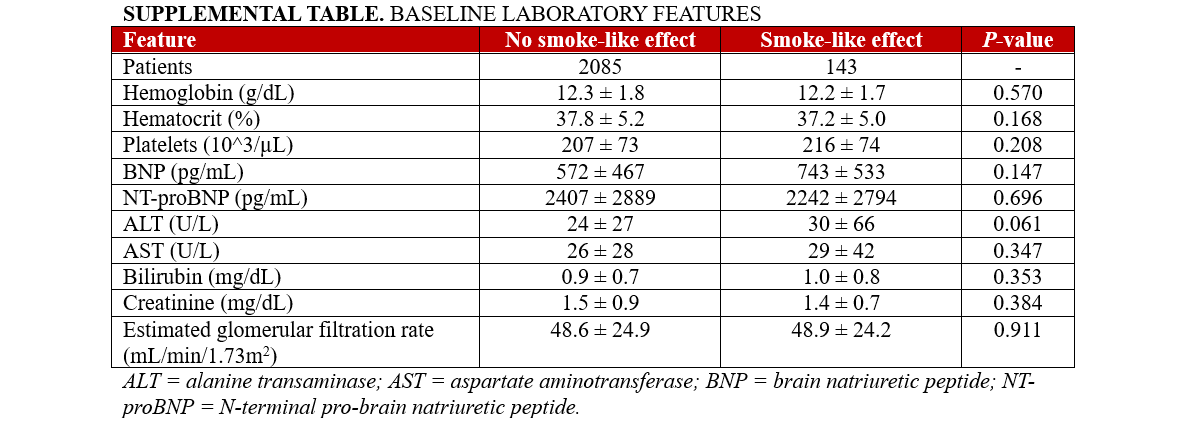

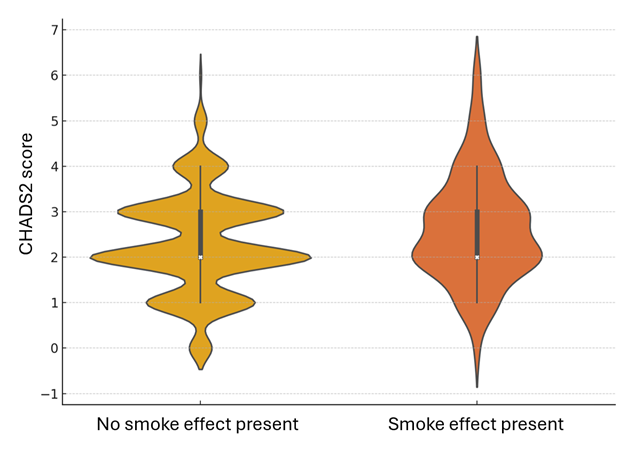

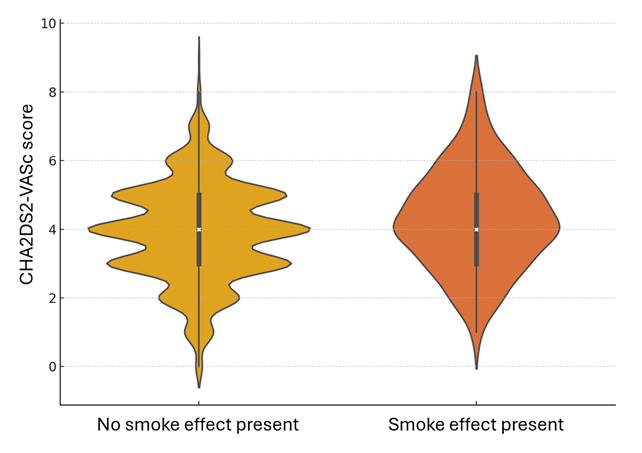

The study included a total of 2228 patients who underwent TEER with the MitraClip device at participating centers between 2016 and 2023, out of which 143 patients (6.4%) exhibited spontaneous echocardiographic contrast at post-procedure TEE. Table 1 and the Supplemental Table highlight baseline clinical characteristics, showing that patients with SE were older (77.8 ± 7.6 vs 75.7 ± 9.3 years), had a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia (60 [42.0%] vs 684 [32.8%]), and were more frequently classified as frail (68 [47.6%] vs 588 [28.2%]). Additionally, they had a higher incidence of prior aortic valve surgery (34 [23.8%] vs 98 [4.7%]) and previous hospitalizations for HF (98 [68.5%] vs 1148 [55.1%]). Furthermore, they were also more likely to be on novel oral anticoagulants (39 [27.3%] vs 494 [23.7%]) and less likely to be on aspirin therapy (47 [32.9%] vs 446 [21.4%]). Intriguingly, both CHADS2 (2.6 ± 1.2 vs 2.3 ± 1.1) and CHA2DS2-VASc (4.3 ± 1.4 vs 3.9 ± 1.4) scores were higher in patients with SE, despite a substantial overlap between the 2 groups (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2).

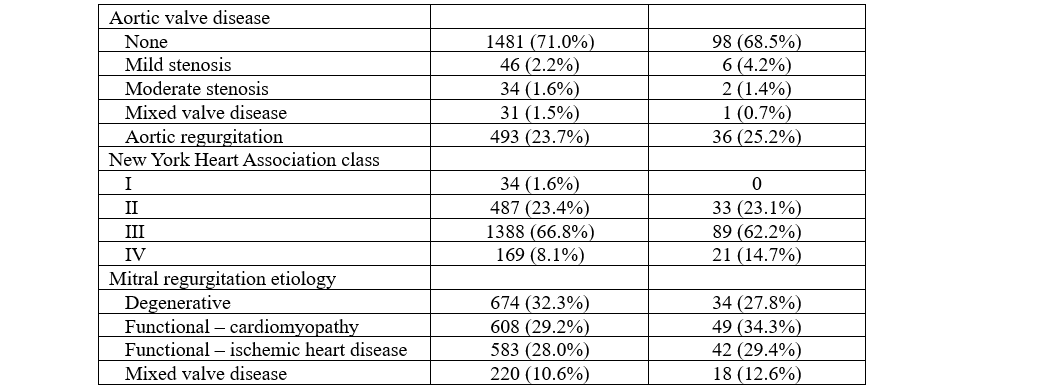

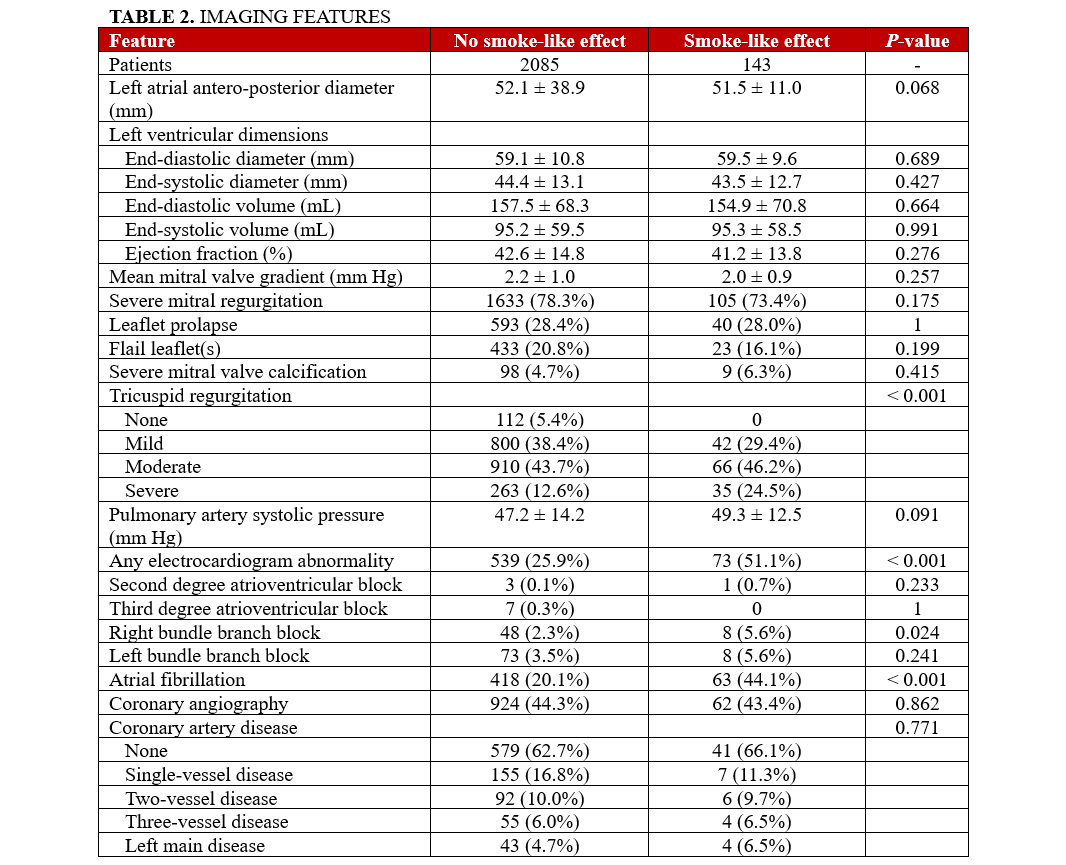

Focusing on electrocardiographic and imaging characteristics (Table 2), the SE group demonstrated a greater prevalence of AF (P < .001) and a higher incidence of significant tricuspid regurgitation. Procedurally (Table 3), the SE group required more MitraClip devices per patient (P = .003), and their procedures were accordingly longer (P = .008 for fluoroscopy times and P = .005 for device time). Despite these differences, the procedural success rates were similar between groups (P = .367), with the SE group showing lower rates of significant MR after TEER (P = .027). Irrespectively, rates of in-hospital outcomes were all similar in patients with or without SE (all P > .05), and the same applied to the length of hospital stay (P = .894).

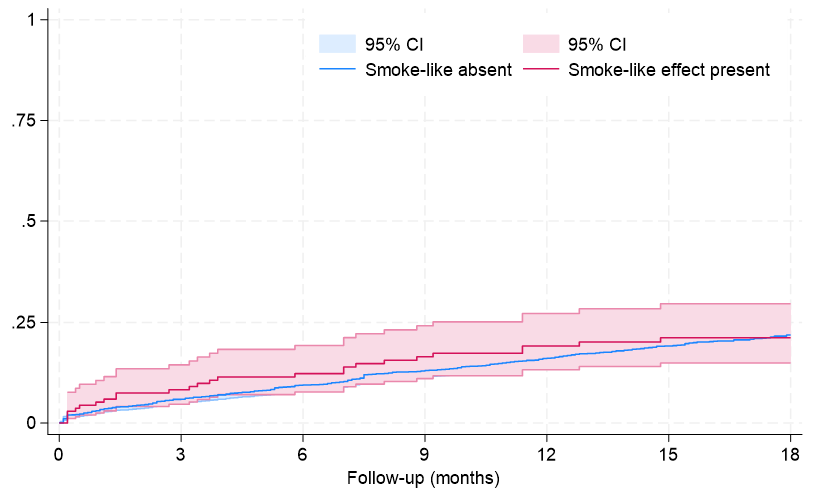

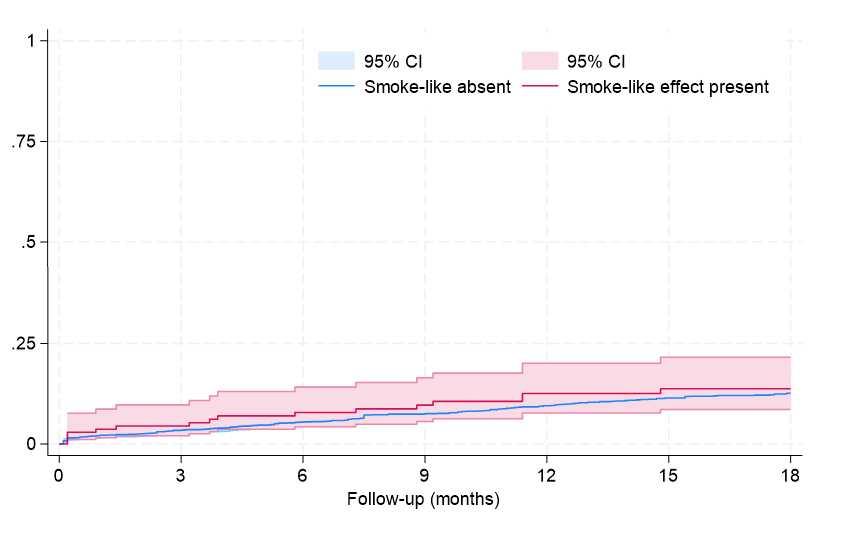

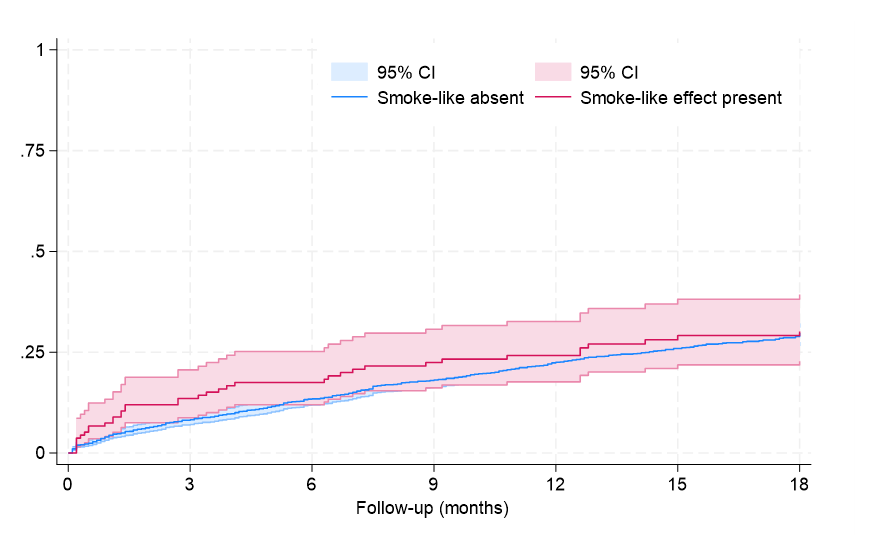

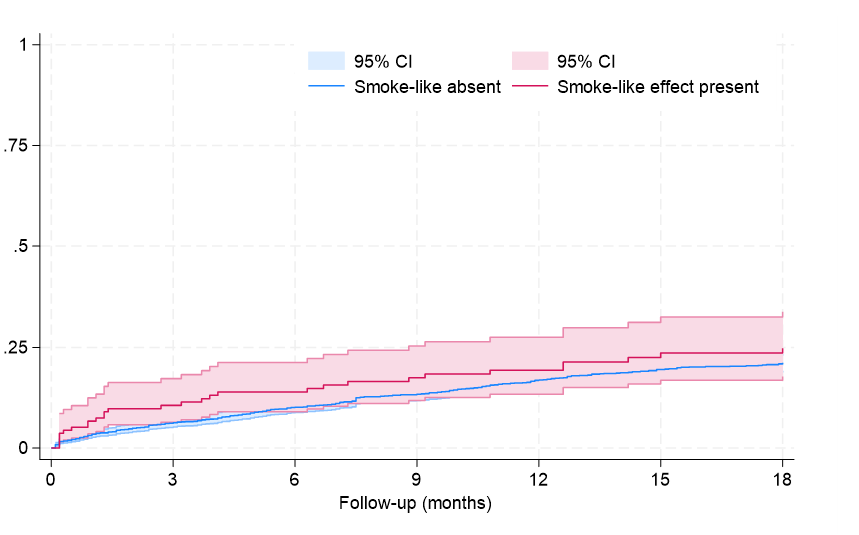

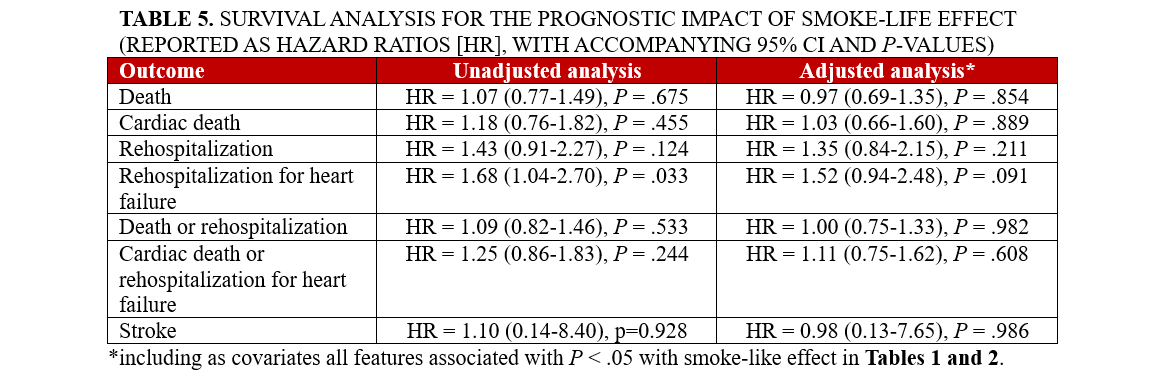

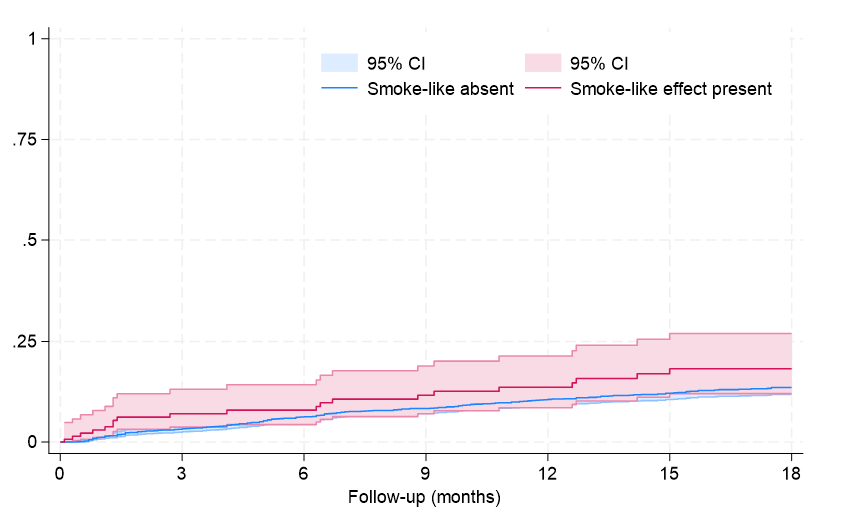

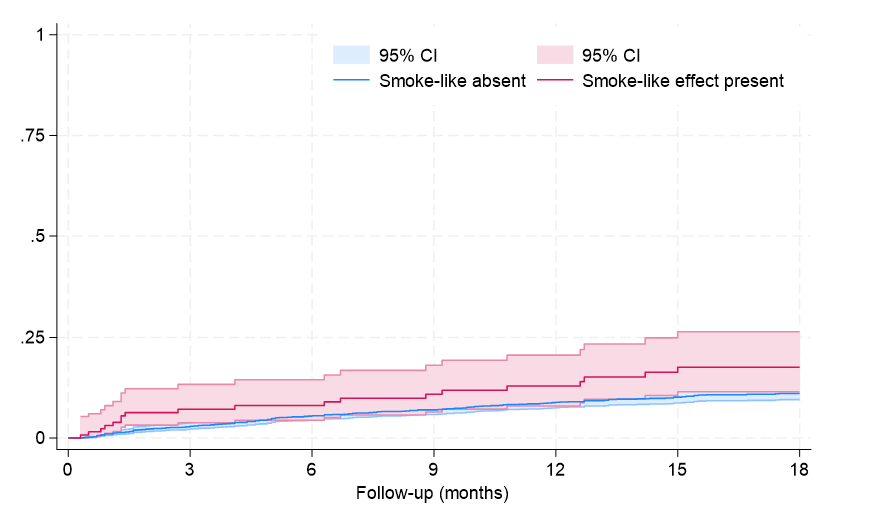

Clinical follow-up showed that, after an average of 19 months, rates of major clinical outcomes, including death, cardiac death, rehospitalization, stroke, death or rehospitalization, and cardiac death or rehospitalization were not significantly different in those with or without SE, at both unadjusted and multivariable adjusted analyses (all P > .05, Figures 1-4, Tables 4 and 5, Supplemental Table 3). The only exception was the risk of rehospitalization for HF, which appeared marginally significant disfavoring the SE group at unadjusted analysis (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.68 [95% CI, 1.04-2.70], P = .033, Supplemental Figure 4). This association was, however, no longer significant when baseline differences were taken into account (HR = 1.52 [95% CI, 0.94-2.48], P = .091).

Discussion

The SE, despite being a relatively common finding in patients with structural heart disease, continues to challenge a univocal interpretation, and this holds true in light of our findings.4,13,20,22 Indeed, in our present study we investigated the incidence, correlates, and outcomes of the occurrence of spontaneous echocardiographic contrast during post-procedure TEE following TEER for significant MR using the MitraClip device. We confirmed that SE is not a remote or rare phenomenon, as it was apparent in more than 6% of patients. Such individuals generally exhibited a more adverse clinical profile, including higher age, greater frailty, increased prevalence of AF and dyslipidemia, and a history of aortic valve surgery or HF hospitalization, in agreement with prior evidence on this topic.6-9,24 Accordingly, these findings align with the current understanding of SE as a marker of underlying cardiac pathology leading to slow and turbulent flow in the left atrium that may be associated with an increased thromboembolic risk. Yet, despite higher rates of AF and oral anticoagulant use in the SE arm, there were numerically more strokes—both hemorrhagic and ischemic—in the non-SE arm. This finding may be due to limitations inherent to the observational design of our work, or depend on the heterogeneity of mechanisms implicated in SE.

The presence of SE was also associated with more complex procedural aspects. Specifically, SE patients required more MitraClip devices and had longer procedure times, both in terms of fluoroscopy and device manipulation. This might reflect the technical challenges and the need for more precise adjustments to achieve optimal MR reduction in these patients. On the other hand, we could speculate that the presence of multiple MitraClips and lesser residual MR may lead to increased blood stagnation in the left atrium and thus a higher risk of SE, even if in our study post-TEER mitral valve gradient was not associated with SE rates. Despite these procedural complexities, the immediate success rates of the TEER procedure were comparable between those with and without SE. This finding suggests that, while SE may indicate a more challenging procedural course, it does not preclude procedural success.

When SE is recognized during or after TEER, a comprehensive diagnostic workup may be considered to evaluate the underlying causes and assess the risk of thromboembolic events, while considering that the evidence base supporting them is very limited. Initial diagnostic tests could include repeat TTE and TEE.5,11 Additionally, cardiac computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging could provide further detail on the structural and functional abnormalities and identify myocardial fibrosis or atrial pathology.25

Several tests can be envisioned in patients with SE, but their clinical usefulness is not yet established. Notwithstanding this important caveat, clinicians may consider measuring levels of D-dimer and fibrinogen levels, and obtaining a complete blood count.6,11,26 In carefully selected individuals with persistent SE or those at high risk for thromboembolic events, anticoagulation therapy may be considered. Antiplatelet therapy with aspirin may also be considered, particularly if there is a concomitant indication such as atherosclerotic disease.27 For patients with SE and concurrent AF, rhythm control strategies, including antiarrhythmic drugs or catheter ablation, might be beneficial in reducing SE and preventing thromboembolic complications.5 In cases where structural heart disease is identified as a contributing factor, such as left atrial enlargement or mitral stenosis, targeted treatments for these conditions can be pursued.8

Long-term follow-up in our study showed that SE was not independently associated with adverse clinical outcomes, with similar findings from Kaplan-Meier survival analyses and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models for the risks of death, cardiac death, rehospitalization, or composite outcomes between patients with and without SE. The only exception was a marginally higher risk of rehospitalization for HF in the SE group, which lost significance after adjusting for baseline differences. These results may imply that SE, while indicative of a more severe clinical presentation, does not independently predict worse long-term outcomes.

The existing literature on SE in the context of cardiac procedures has highlighted its association with hypercoagulable states and increased thromboembolic events.6,11,27 However, our findings suggest that in the specific context of TEER with MitraClip, SE should not necessarily lead to more aggressive antithrombotic therapy unless other clinical indications are present. This aligns with previous reports indicating that the clinical management of SE should be guided by a comprehensive assessment of the patient's overall risk profile rather than the presence of SE alone.13

Limitations

Limitations of this study include its observational design and the inherent potential for selection bias, as the decision to attempt TEER and the specific procedural strategies employed were at the discretion of the treating physicians. Notably, the lack of grading or quantification of SE is a distinct limitation of our work, as well as the lack of estimates on inter- and intra-individual variability (which, however, can be expected to be reasonably high).28-29 The careful reader can attentively peruse several works dedicated to SE quantification, ranging from categorical scoring to automated quantification based on machine learning tools.30-32 Another key limitation of our work is the lack of laboratory data for coagulation as well as clinically guided echocardiographic follow-up, which cannot inform on the persistence or disappearance of SE over days or months, as it was not systematic nor mandatory at different time points. Additionally, while the GIOTTO registry provides a robust data set, the lack of independent clinical monitoring and imaging core-lab analysis may affect the precision of certain measurements.

Conclusions

The presence of SE post-TEER with the MitraClip device is associated with a more adverse baseline clinical profile and more complex procedural requirements but does not independently predict adverse short- or long-term clinical outcomes. These findings suggest that SE should not be considered a standalone indicator for more aggressive therapeutic strategies, but rather a component of a comprehensive risk assessment to guide clinical decision-making.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Nicola Corcione, MD1; Paolo Ferraro, MD2; Filippo Finizio, MD1; Michele Cimmino, MD1; Michele Albanese, MD2; Alberto Morello, MD1; Giuseppe Biondi-Zoccai, MD, MStat3,4; Paolo Denti, MD5; Antonio Popolo Rubbio, MD6; Francesco Bedogni, MD6; Antonio L. Bartorelli, MD7; Annalisa Mongiardo, MD8; Salvatore Giordano, MD8; Francesco De Felice, MD9; Marianna Adamo, MD10; Matteo Montorfano, MD11; Francesco Maisano, MD11; Giuseppe Tarantini, MD12; Francesco Giannini, MD13; Federico Ronco, MD14; Emmanuel Villa, MD15; Maurizio Ferrario, MD16; Luigi Fiocca, MD17; Fausto Castriota, MD18; Angelo Squeri, MD18; Martino Pepe, MD19; Corrado Tamburino, MD20; Arturo Giordano, MD, PhD1

From the 1Unità Operativa di Interventistica Cardiovascolare, Pineta Grande Hospital, Castel Volturno, Italy; 2Unità Operativa di Emodinamica, Santa Lucia Hospital, San Giuseppe Vesuviano, Italy; 3Department of Medico-Surgical Sciences and Biotechnologies, Sapienza University of Rome, Latina, Italy; 4Maria Cecilia Hospital, GVM Care & Research, Cotignola, Italy; 5Department of Cardiac Surgery, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy; 6Department of Cardiology, IRCCS Policlinico San Donato, San Donato Milanese, Milan, Italy; 7IRCCS Ospedale Galeazzi-Sant’Ambrogio, Milan, Italy, and Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, University of Milan, Milan, Italy; 8Division of Cardiology, Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, "Magna Graecia" University; 9Division of Interventional Cardiology, Azienda Ospedaliera S. Camillo Forlanini, Rome, Italy; 10Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory and Cardiology, ASST Spedali Civili di Brescia, and Department of Medical and Surgical Specialties, Radiological Sciences, and Public Health University of Brescia, both in Brescia, Italy; 11School of Medicine, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan, Italy; Interventional Cardiology Unit, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy; 12Department of Cardiac, Thoracic and Vascular Science, Interventional Cardiology Unit, University of Padua, Padua, Italy; 13Division of Cardiology, IRCCS Ospedale Galeazzi - Sant'Ambrogio, Milan, Italy; 14Interventional Cardiology, Department of Cardio-Thoracic and Vascular Sciences, Ospedale dell'Angelo, AULSS3 Serenissima, Mestre, Venezia, Italy; 15Cardiac Surgery Unit and Valve Center, Poliambulanza Foundation Hospital, Brescia, Italy; 16Division of Cardiology, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico S. Matteo, Pavia, Italy; 17Cardiovascular Department, Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital, Bergamo, Italy; 18Interventional Cardiology Unit, GVM Care & Research, Maria Cecilia Hospital, Cotignola, Italy; 19Division of Cardiology, Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine (D.I.M.), University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy; 20Division of Cardiology, Centro Alte Specialità e Trapianti (CAST), Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Policlinico-Vittorio Emanuele, University of Catania, Catania, Italy.

Acknowledgments: This manuscript was revised and illustrated with the assistance of artificial intelligence tools, such as ChatGPT 4 (OpenAI). The final content, including all conclusions and opinions, has been thoroughly revised, edited, and approved by the authors. The authors take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the work and retain full credit for all intellectual contributions. Compliance with ethical standards and guidelines for the use of artificial intelligence in research has been ensured.

Disclosures:The remaining authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Funding: Dr Biondi-Zoccai has consulted for Aleph, Amarin, Balmed, Cardionovum, Crannmedical, Endocore Lab, Eukon, Guidotti, Innovheart, Meditrial, Menarini, Microport, Opsens Medical, Terumo, and Translumina, outside of the present work. The GIOTTO (GIse registry Of Transcatheter treatment of mitral valve regurgitaTiOn) registry is sponsored by the Italian Society of Invasive Cardiology, with an unrestricted grant by Abbott Vascular.

Address for correspondence: Giuseppe Biondi-Zoccai, MD, Mstat, Department of Medical-Surgical Sciences and Biotechnologies, Sapienza University of Rome, Latina, Italy. Email: giuseppe.biondizoccai@uniroma1.it; X: @gbiondizoccai

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Violin plot for CHADS2 scores in patients with vs without smoke effect (P < .001).

Supplemental Figure 2. Violin plot for CHA2DS2-VASc scores in patients with vs without smoke effect (P = .001).

Supplemental Figure 3. Failure curves for rehospitalization (P = .099 at Tarone-Ware test).

Supplemental Figure 4. Failure curves for rehospitalization for heart failure (P = .028 at Tarone-Ware test).

References

1. Feldman T, St Goar F, eds. Percutaneous Mitral Leaflet Repair: MitraClip Therapy for Mitral Regurgitation. Informa; 2012.

2. Kataoka A, Watanabe Y; OCEAN-SHD Family. MitraClip: a review of its current status and future perspectives. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2023;38(1):28-38. doi:10.1007/s12928-022-00898-4

3. van-Roessel AM, Asmarats L, Li CHP, et al. Mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair: patient selection, current devices, and clinical outcomes. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2024;21(3):187-196. doi:10.1080/17434440.2023.2298713

4. Ito T, Suwa M. Left atrial spontaneous echo contrast: relationship with clinical and echocardiographic parameters. Echo Res Pract. 2019;6(2):R65-R73. doi:10.1530/ERP-18-0083

5. Chen L, Zinda A, Rossi N, et al. A new risk model of assessing left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with atrial fibrillation - using multiple clinical and transesophageal echocardiography parameters. Int J Cardiol. 2020;314:60-63. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.04.039

6. Kelesoglu S, Elcık D, Zengin I, et al. Association of spontaneous echo contrast with Systemic Immune Inflammation Index in patients with mitral stenosis. Rev Port Cardiol. 2022;41(12):1001-1008. doi:10.1016/j.repc.2021.08.016

7. Aslanabadi N, Separham A, Valae Hiagh L, et al. Association of mean platelet volume with echocardiographic findings in patients with severe rheumatic mitral stenosis. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2019;11(2):95-99. doi:10.15171/jcvtr.2019.17

8. Sahin O, Savas G. Relationship between presence of spontaneous echo contrast and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with mitral stenosis. Echocardiography. 2019;36(5):924-929. doi:10.1111/echo.14338

9. Gülcihan Balcı K, Maden O, Balcı MM, et al. The association between mean platelet volume and spontaneous echocardiographic contrast or left atrial thrombus in patients with mitral stenosis. Anatol J Cardiol. 2016;16(11):863-867. doi:10.14744/AnatolJCardiol.2015.6675

10. Beppu S. Hypercoagulability in the left atrium: Part I: echocardiography. J Heart Valve Dis. 1993;2(1):18-24.

11. Sato H, Cavalcante JL, Enriquez-Sarano M, et al. Significance of spontaneous echocardiographic contrast in transcatheter edge-to-edge repair for mitral regurgitation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2023;36(1):87-95. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2022.08.010

12. Tsunamoto H, Yamamoto H, Takahashi N, Takaya T. Newly developed spontaneous echocardiographic contrast as a potential marker of intracardiac thrombus formation after a transcatheter edge-to-edge mitral valve repair. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2022;6(4):ytac146. doi:10.1093/ehjcr/ytac146

13. Ohno Y, Attizzani GF, Capodanno D, et al. Acute left atrial spontaneous echocardiographic contrast and suspicious thrombus formation following mitral regurgitation reduction with the MitraClip system. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7(11):1322-1323. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2014.04.027

14. Bedogni F, Testa L, Rubbio AP, et al. Real-world safety and efficacy of transcatheter mitral valve repair with MitraClip: thirty-day results from the Italian Society of Interventional Cardiology (GIse) Registry Of Transcatheter Treatment of Mitral Valve RegurgitaTiOn (GIOTTO). Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020;21(9):1057-1062. doi:10.1016/j.carrev.2020.01.002

15. Giordano A, Biondi-Zoccai G, Finizio F, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of MitraClip in octogenarians: evidence from 1853 patients in the GIOTTO registry. Int J Cardiol. 2021;342:65-71. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.08.010

16. Giordano A, Ferraro P, Finizio F, et al. Implantation of one, two or multiple MitraClip™ for transcatheter mitral valve repair: insights from a 1824-patient multicenter study. Panminerva Med. 2022;64(1):1-8. doi:10.23736/S0031-0808.21.04497-9

17. Giordano A, Pepe M, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Impact of coronary artery disease on outcome after transcatheter edge-to-edge mitral valve repair with the MitraClip system. Panminerva Med. 2023;65(4):443-453. doi:10.23736/S0031-0808.23.04827-9

18. Giordano A, Ferraro P, Finizio F, et al. Transcatheter mitral valve repair with the MitraClip device for prior mitral valve repair failure: insights from the GIOTTO-FAILS study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13(10):e033605. doi:10.1161/JAHA.123.033605

19. Giordano A, Ferraro P, Finizio F, et al. Incidence and predictors of cerebrovascular accidents in patients who underwent transcatheter mitral valve repair with MitraClip. Am J Cardiol. 2024;228:24-33. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2024.07.037

20. Black IW. Spontaneous echo contrast: where there's smoke there's fire. Echocardiography. 2000;17(4):373-382. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8175.2000.tb01153.x

21. Briley DP, Giraud GD, Beamer NB, et al. Spontaneous echo contrast and hemorheologic abnormalities in cerebrovascular disease. Stroke. 1994;25(8):1564-1569. doi:10.1161/01.str.25.8.1564

22. Ito T, Suwa M. Left atrial spontaneous echo contrast: relationship with clinical and echocardiographic parameters. Echo Res Pract. 2019;6(2):R65-R73. doi:10.1530/ERP-18-0083

23. Yaghi S, Kamel H, Elkind MSV. Atrial cardiopathy: a mechanism of cryptogenic stroke. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2017;15(8):591-599. doi:10.1080/14779072.2017.1355238

24. Tabrizi MT, Girardo M, Naqvi TZ. In situ transesophageal echocardiography during electrical cardioversion in patients with atrial fibrillation-safety and echocardiographic findings. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2024;37(4):420-427. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2023.11.022

25. Levin A, Miller R, Tiwari N, Guelfguat M. Case report: use of unenhanced cardiac MR to evaluate low flow states for thrombus. Radiol Case Rep. 2022;17(11):4341-4344. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2022.08.066

26. Santoro F, Núñez-Gil IJ, Viana-Llamas MC, et al. Anticoagulation therapy in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: results from a multicenter international prospective registry (Health Outcome Predictive Evaluation for Corona Virus Disease 2019 [HOPE-COVID19]). Crit Care Med. 2021;49(6):e624-e633. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000005010

27. Bursi F, Santangelo G, Ferrante G, Massironi L, Carugo S. Prevalence of left atrial thrombus by real time three-dimensional echocardiography in patients undergoing electrical cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: a contemporary cohort study. Echocardiography. 2021;38(4):518-524. doi:10.1111/echo.15015

28. Kronik G, Stöllberger C, Schuh M, Abzieher F, Slany J, Schneider B. Interobserver variability in the detection of spontaneous echo contrast, left atrial thrombi, and left atrial appendage thrombi by transoesophageal echocardiography. Br Heart J. 1995;74(1):80-83. doi:10.1136/hrt.74.1.80

29. Akamatsu K, Ito T, Ozeki M, Miyamura M, Sohmiya K, Hoshiga M. Left atrial spontaneous echo contrast occurring in patients with low CHADS2 or CHA2DS2-VASc scores. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2020;18(1):31. doi:10.1186/s12947-020-00213-2

30. Fatkin D, Kelly RP, Feneley MP. Relations between left atrial appendage blood flow velocity, spontaneous echocardiographic contrast and thromboembolic risk in vivo. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23(4):961-969. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(94)90644-0

31. Klein AL, Murray RD, Black IW, et al. Integrated backscatter for quantification of left atrial spontaneous echo contrast. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28(1):222-231. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(96)00131-3

32. Huang O, Shi Z, Garg N, Jensen C, Palmeri ML. Automated spontaneous echo contrast detection using a multisequence attention convolutional neural network. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2024;50(6):788-796. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2024.01.016