Hospital Outcomes of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction-Related Cardiogenic Shock With and Without Revascularization

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2025. doi:10.25270/jic/25.00204. Epub October 29, 2025.

Abstract

Objectives. An early invasive strategy is recommended for patients with acute myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock (AMICS). However, data on outcomes of patients undergoing early coronary angiography (CA) without subsequent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are limited. The authors examined the characteristics and outcomes of patients with AMICS who underwent early CA and were treated with or without acute PCI.

Methods. The authors analyzed data from the prospective Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische Krankenhausärzte (ALKK) CA registry. Patient characteristics, indications for CA, treatments, and in-hospital outcomes were collected and analyzed. All patients who underwent CA for AMICS were included.

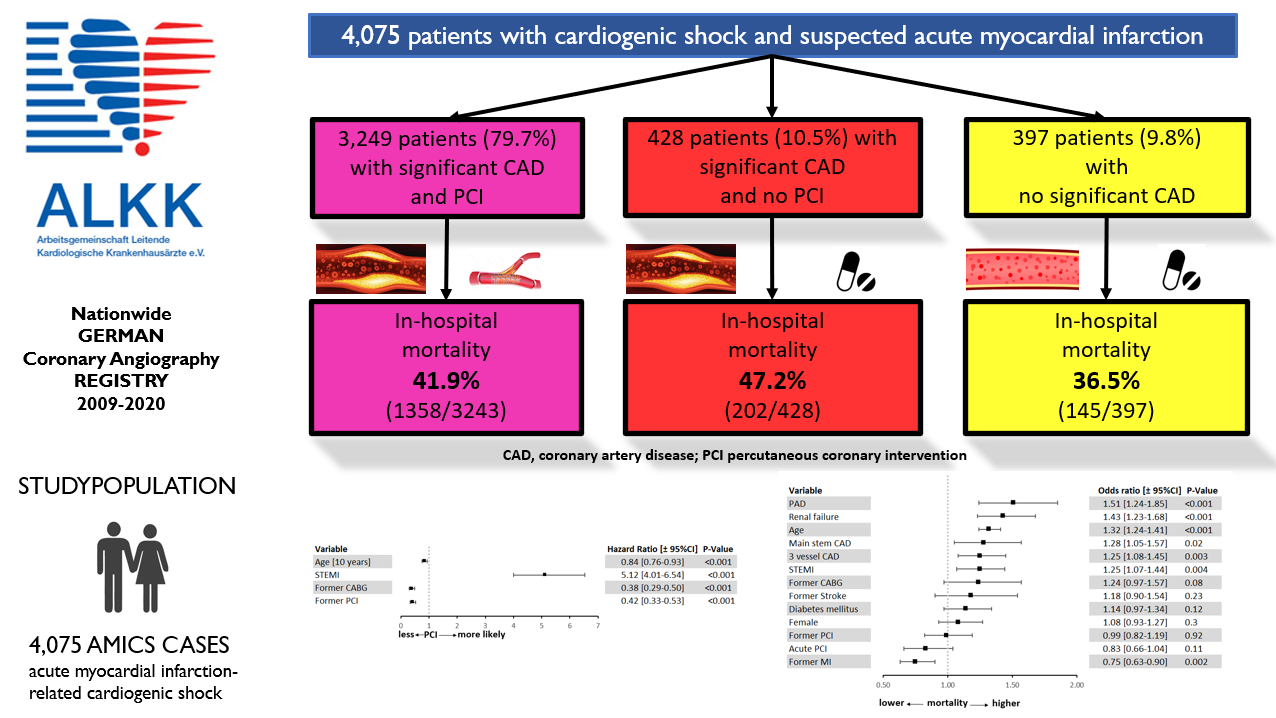

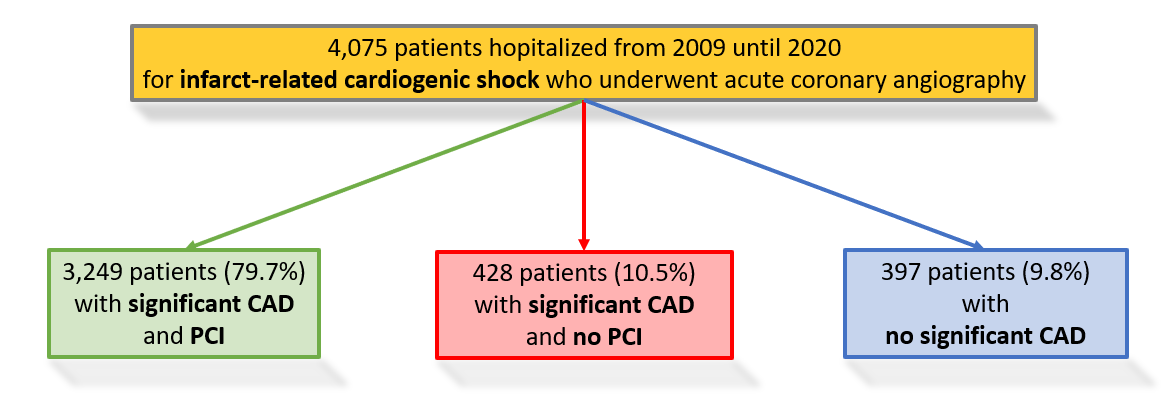

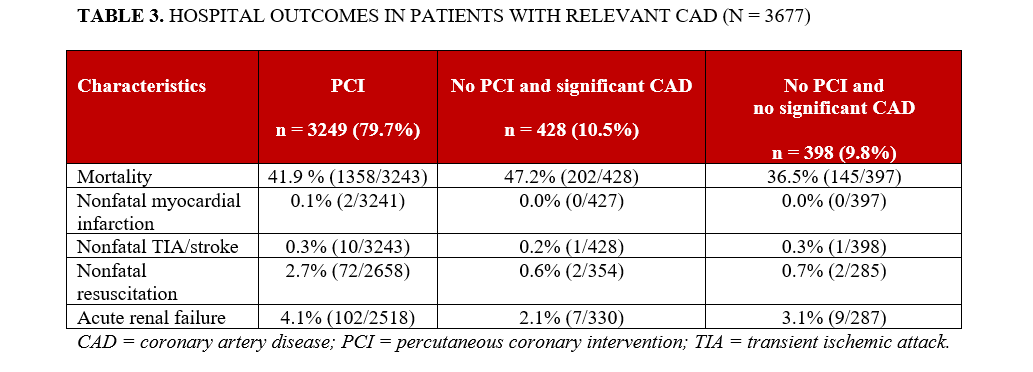

Results. Between January 2009 and December 2020, 4290 patients with AMICS underwent CA within 24 hours after symptom onset. Patients referred to urgent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) were excluded. Among the remaining 4075 patients, 3249 (79.7%) underwent acute PCI, 428 (10.5%) had significant coronary artery disease (CAD) but were not treated with PCI, and 398 (9.8%) had no significant CAD. Patients who did not undergo PCI were older and more likely to have a history of prior PCI or CABG. The in-hospital mortality rate was 47.2% among patients without PCI, 41.9% among those treated with PCI, and 36.5% among those without significant CAD.

Conclusions. In this large, contemporary CA registry, approximately 10% of AMICS patients had significant CAD but did not undergo acute PCI; this subgroup exhibited high in-hospital mortality. Another 10% of patients had no significant CAD, with one-third dying during hospitalization. Further studies are needed to identify strategies to improve outcomes in these populations.

Introduction

Despite advances in pharmacologic, interventional, device-based, and surgical therapies, mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock (AMICS) has remained high over the past decades.1-5 According to current guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation1, and those for acute coronary syndromes without persistent ST-segment elevation,6 an early invasive strategy with prompt revascularization—preferably by primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)—is recommended for patients with AMICS. Nevertheless, the rate of PCI in AMICS in real-world clinical practice varies widely, ranging from 55% to 88%.5,7-9

The aim of the present study was to examine the clinical characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of patients with AMICS who underwent early coronary angiography (CA) and were treated either with or without acute PCI.

Methods

Patients included in the present analysis were enrolled in the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische Krankenhausärzte (ALKK) CA registry, the design of which has been described previously.3,6,7 Briefly, the ALKK-CA registry is a prospective multicenter registry initiated in 1992 to support quality control. It includes all consecutive procedures from participating hospitals on an intention-to-treat basis.

Data on patient medical history, indications for the procedure, adjunctive antithrombotic therapy, and in-hospital complications were collected using standardized case report forms across the 42 participating hospitals. All data were centrally analyzed at the Stiftung Institut für Herzinfarktforschung in Ludwigshafen, Germany.

Definitions

Cardiogenic shock was defined as a systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mmHg, a heart rate of greater than 100 beats per minute, and clinical signs of end-organ hypoperfusion, such as cold and clammy skin, oliguria, altered mental status, or elevated serum lactate. Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) was diagnosed when both of the following 2 criteria were met: (1) persistent angina pectoris lasting greater than or equal to 20 minutes, and (2) elevated troponin T or I concentrations above the upper limit of normal as defined by the local laboratory.

ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) was diagnosed when both of the following criteria were present: (1) persistent angina pectoris lasting greater than or equal to 20 minutes and (2) ST-segment elevation of 1 mm in greater than or equal to 2 contiguous limb leads or greater than or equal to 2 mm in greater than or equal to 2 contiguous precordial leads, or the presence of a new left bundle branch block. The diagnosis was confirmed by a rise in cardiac biomarkers (troponin, creatine kinase and/or its MB) to at least twice the normal value.

Patients who were referred to coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) after diagnostic CA (n = 215) were excluded from this analysis because most of them were transferred to other hospitals and therefore lost to follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). The study population is presented as absolute numbers, percentages, and medians with 25th and 75th percentiles, as appropriate. Differences in categorical variables were assessed using the Pearson χ2 test. Odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% CIs were calculated to estimate effect sizes. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test.

A logistic regression model (binary logit, optimized by Fisher’s scoring) was applied to identify independent predictors of PCI recommendation and in-hospital mortality. Statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided P-value of less than or equal to 0.05. All P-values are reported on an exploratory basis.

Results

From January 2009 through December 2020, a total of 4290 patients with AMICS from 42 hospitals were enrolled in the ALKK CA registry. All patients underwent CA within 24 hours after symptom onset. Patients with an indication for urgent CABG (n = 215) were excluded, leaving 4075 patients for the present analysis.

Among these, 91.2% (n = 3 677) had significant coronary artery disease (CAD; coronary stenosis >50%). Acute PCI was performed in 79.7% (n = 3 249) of these patients, whereas 10.5% (n = 428) of patients with relevant CAD were treated conservatively. The remaining 9.8% (n = 398) of patients had no relevant CAD (Figure 1).

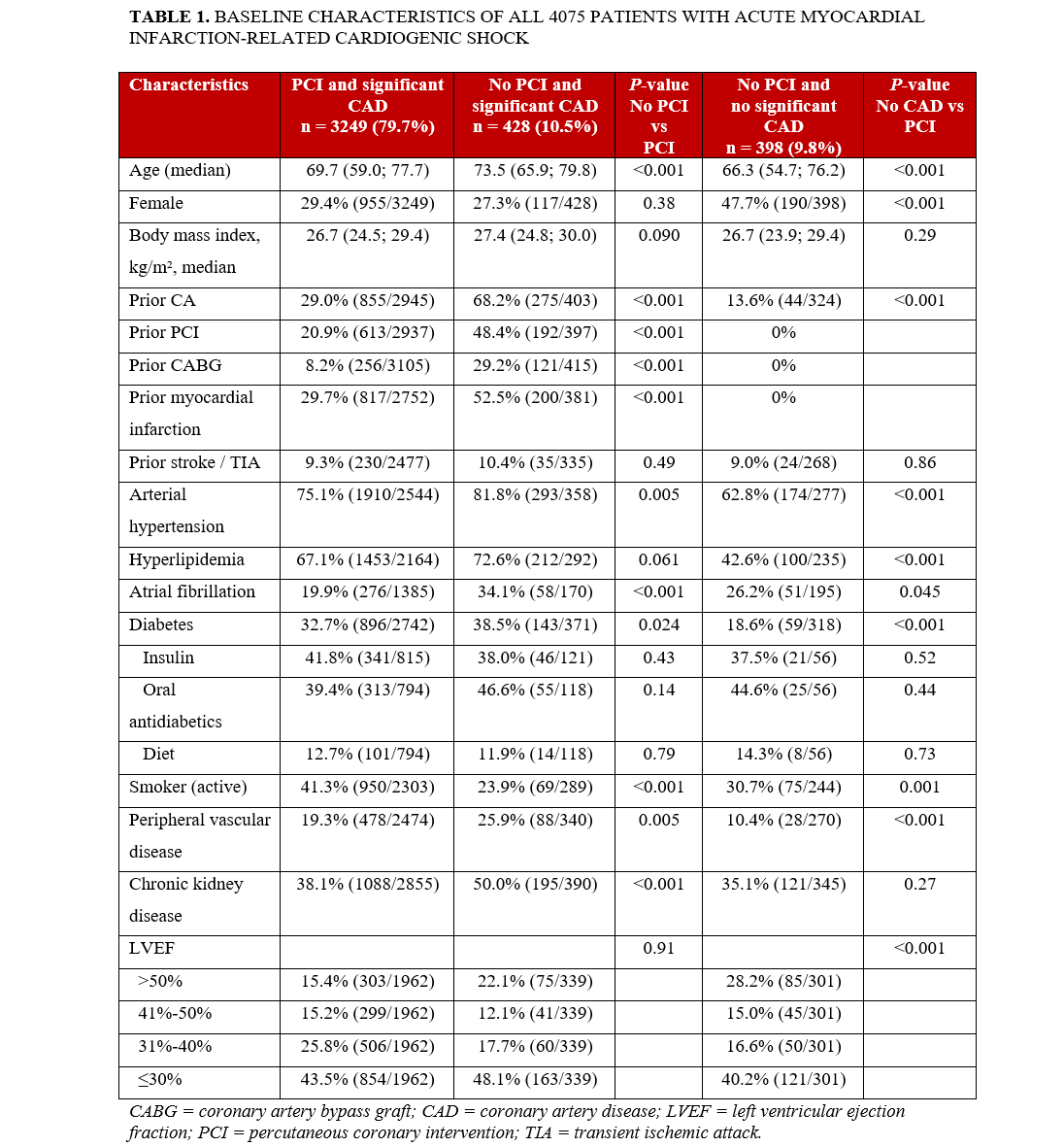

The baseline characteristics of patients with AMICS are summarized in Table 1. In the group with CAD but without PCI, previous CA, prior PCI, previous myocardial infarction, and prior CABG were more common. Atrial fibrillation and peripheral vascular disease were also more prevalent in this group. A moderately reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (31%-50%) was observed more frequently in the PCI group, whereas a preserved ejection fraction (>50%) was more common in patients who did not undergo PCI. Forty-one percent (n = 950/2303) of patients with significant CAD and recommendation for PCI were active smokers, whereas 24% (n = 69/289) of patients with significant CAD without recommendation for PCI were smokers. Interestingly, 31% (n = 75/244) of patients without significant CAD were also smokers.

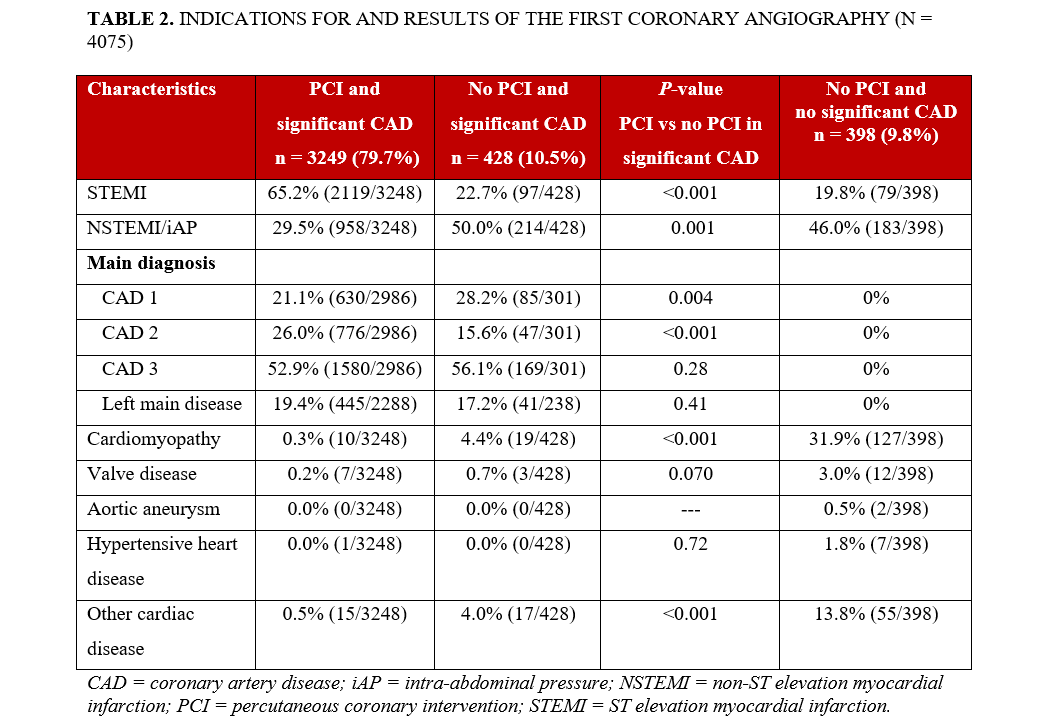

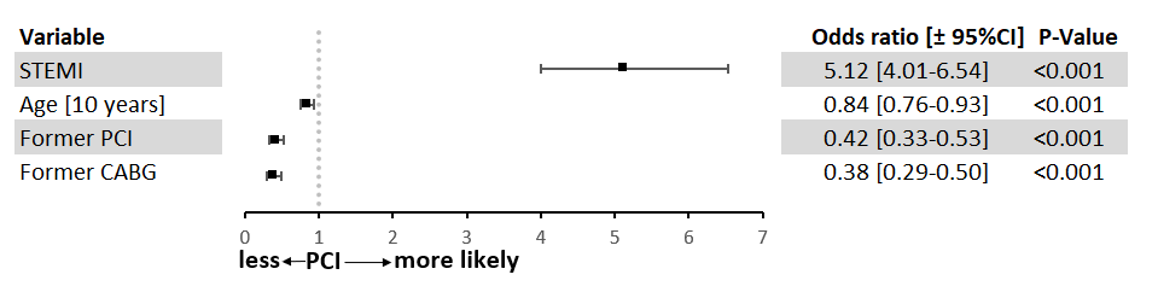

The indication for the first CA was most often STEMI in the PCI group and NSTEMI in the other 2 groups (Table 2). Independent predictors for not performing PCI are shown in Figure 2. The model was adjusted for age, STEMI, prior CABG, and prior PCI. In patients with STEMI, the likelihood of undergoing acute PCI was higher than in those with NSTEMI, whereas prior CABG or PCI and increasing age were associated with a lower likelihood of acute PCI.

Findings from diagnostic CA are summarized in Table 2. The most frequent final diagnoses in patients without significant CAD were cardiomyopathy (32%; n = 127), other cardiac disease (14%; n = 55), valvular heart disease (3%; n= 12), hypertensive heart disease (2%; n= 7), and aortic aneurysm (0.5%; n= 2).

In-hospital mortality was higher among patients who did not undergo PCI compared with those who did. Nonfatal resuscitation occurred more often in the non-PCI group, whereas the rates of nonfatal myocardial infarction and nonfatal transient ischemic attack or stroke did not differ significantly between groups (Table 3).

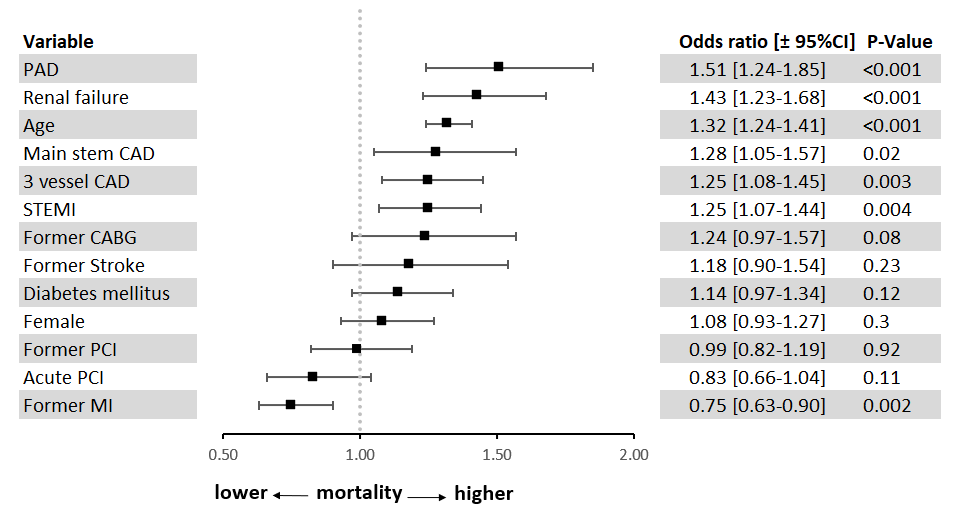

Independent predictors of increased in-hospital mortality were peripheral artery disease (PAD), renal failure, age, left main CAD, 3-vessel CAD, and STEMI (Figure 3). The model was adjusted for PAD, renal failure, age, left main CAD, 3-vessel CAD, STEMI, prior CABG, PCI status, previous stroke, diabetes mellitus, sex, prior PCI, and previous myocardial infarction.

Discussion

In this large CA registry, we analyzed patients with AMICS who underwent early CA and were treated with or without PCI. The principal finding of our analysis was that 11.6% (n = 428) of all patients with AMICS and significant CAD did not receive acute PCI. Patients without significant CAD likewise did not undergo any revascularization therapy (9.8%, n = 398). In-hospital mortality among patients with CAD but without PCI was higher than among those who received PCI, although the difference was smaller than expected (47.2% vs 41.9%). Notably, patients without relevant CAD had the lowest in-hospital mortality; however, 1 in 3 (36.5%) patients in this group still died during hospitalization.

Our observed in-hospital mortality rates were lower than those reported in a large US registry, where patients with cardiogenic shock managed conservatively had an in-hospital mortality of 59.7%.9 Similarly, patients with cardiogenic shock enrolled in the Bremen STEMI Registry who received no intervention had in-hospital and 1-year mortality rates of 70% and 76%, respectively.10 In a representative US cohort (January 2002 to December 2014; n = 118 618), approximately 53% of patients with AMICS did not undergo any acute revascularization and had an in-hospital mortality of 52.2%.8 In that study, older age, female sex, weekend admission, heart failure, septic shock, resuscitation, and renal failure were predictors of conservative management in AMICS. In our population, STEMI was the strongest predictor of undergoing PCI, whereas older patients and those with prior CABG or prior PCI were treated less often with PCI.

One explanation for the lower mortality in our cohort may be that patients undergoing diagnostic CA in our registry represented a preselected population with a more favorable risk profile than those who did not undergo CA. This selection bias likely contributed to the better survival observed in our analysis. Patients who could not be stabilized on arrival, those with prolonged out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and severe neurologic deficits or hypoxic injury, and patients with major comorbidities or extreme frailty were unlikely to receive acute CA and were therefore not included. Because documentation of the reasons for not performing acute PCI in patients with AMICS was not mandatory in the ALKK registry, potential explanations remain speculative. Possible causes include the absence of an identifiable culprit lesion after spontaneous reperfusion; diffuse, end-stage CAD without a suitable target for stenting; severe left main disease not amenable to PCI with patients unsuitable for urgent surgery; chronic total occlusions not feasible for emergency intervention; or marked calcification or tortuosity of the coronary arteries making PCI technically impossible. Other potential reasons may have been an extremely poor prognosis after prolonged cardiac arrest with anoxic brain injury, multiorgan failure, or mechanical complications (e.g. papillary muscle rupture, free-wall rupture, ventricular septal defect) where revascularization was unlikely to confer benefit. Severe comorbidities such as advanced malignancy or end-stage chronic disease may also have precluded invasive revascularization, and, in some cases, families declined further invasive therapy.

Patients who underwent unsuccessful PCI had a worse prognosis than those managed without PCI.11 Restoration of coronary blood flow remains a major determinant of survival in patients with cardiogenic shock and significant CAD.12,13

In summary, this analysis of a large CA registry confirms that mortality in AMICS remains very high. Patients with significant CAD who did not undergo PCI had the highest in-hospital mortality (about 50%). In patients with cardiogenic shock but without relevant CAD, mortality was lower, yet more than one-third died during hospitalization. The reasons for withholding acute revascularization are complex but often clinically justifiable.14 In our registry, specific reasons for not performing PCI were not recorded.

Limitations

The diagnosis of cardiogenic shock was made by the local investigators based on clinical judgment, as no strict prespecified criteria were mandated. Nevertheless, the consistently high mortality rate and stable proportion of shock patients over time make it unlikely that the inclusion of patients who did not fulfill formal hemodynamic criteria significantly influenced the results.

There were no exclusion criteria regarding comorbid conditions; therefore, this cohort reflects real-world experience in patients with AMICS. Treatment decisions were left to the discretion of the attending physicians, and no information was available regarding the specific reasons why revascularization therapy was withheld. As with all observational studies, selection bias cannot be fully excluded.

Because our analysis included patients treated between 2009 and 2020, data on the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions shock classification—introduced in 2019—were not available. Information on the use of the Impella device (Abiomed) was also lacking, as it was not routinely employed during most of the study period. Similarly, the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was rare in Germany 10 to 15 years ago.

Conclusions

In this large, real-world CA registry, approximately 10% of patients with AMICS who underwent acute CA had significant CAD but were not treated with PCI. In-hospital mortality in this group approached 50%. Another 10% of patients with AMICS had no significant CAD; although their mortality was lower, more than one-third still died during hospitalization. Further studies are needed to identify strategies that can improve outcomes in these high-risk patient populations.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Tobias Heer, MD1; Matthias Hochadel, MD2; Sebastian Kerber, MD3; Bernward Lauer, MD4; Ralf Zahn, MD5; Uwe Zeymer, MD2,6; for the ALKK study group

From the 1München Klinik Neuperlach, Academic Teaching Hospital, Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich, Munich, Germany; 2Stiftung Institut für Herzinfarktforschung Ludwigshafen, Ludwigshafen, Germany; 3Klinik für Kardiologie, Herz- und Gefäß-Klinik GmbH, Bad Neustadt an der Saale, Germany; 4Klinik für Innere Medizin I, Universitätsklinikum, Jena, Germany; 5Medizinische Klinik B, Klinikum der Stadt Ludwigshafen, Ludwigshafen, Germany; 6Department of Cardiology and Angiology, University Heart Center Freiburg-Bad Krozingen, Faculty of Medicine, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany.

Disclosures: The authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Address for correspondence: Tobias Heer, MD, München Klinik Neuperlach, Academic Teaching Hospital, Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich, Department of Cardiology, Oskar-Maria-Graf-Ring 51, Munich D-81737, Germany. Email: tobias.heer@muenchen-klinik.de

Supplemental Material

List of participants of the ALKK coronary angiography registry:

Herz- und Gefäß-Klinik GmbH, Bad Neustadt (Sebastian Kerber), Herzzentrum Ludwigshafen (Uwe Zeymer, Ralf Zahn), Klinikum Oldenburg (Albrecht Elsässer), Krankenhaus d. Barmherzigen Brüder, Trier (Karl-E. Hauptmann, Nikos Werner), Alfried Krupp v. Bohlen Krankenhaus gGmbH, Essen (Thomas Budde, Hagen Kälsch), VIVANTES-Klinikum Berlin-Neukölln (Harald Darius, Huseyin Ince), Klinikum Coburg gGmbH (Johannes Brachmann, Eckart Flach), Klinikum Spandau, Berlin (Steffen Behrens), Kreiskrankenhaus Landshut-Achdorf (Bernhard Zrenner, Julinda Mehilli), Klinikum Wetzlar-Braunfels (Wilfried Kramer, Martin Brück), Humboldt-Klinikum Berlin (Steffen Behrens), Kreiskrankenhaus Biberach (Jobst Isbary, Thomas Brummer, Christian Vollmer), Westpfalz-Klinikum GmbH - Standort I Kaiserslautern (H.-G. Glunz, Burghard Schumacher), Krankenhaus am Urban, Berlin (Dietrich Andresen, Hüseyin Ince), Zentralklinik Bad Berka GmbH (Bernward Lauer, Philipp Lauten), Klinikum Fulda (Volker Schächinger), Klinikum im Friedrichshain, Berlin (Steffen Behrens, Stephan Kische), Vinzenzkrankenhaus Hannover (Christian Zellerhoff), Klinikum München Neuperlach (Harald Mudra, Stefan Sack), Auguste-Viktoria-Krankenhaus, Berlin (Helmut Schühlen, Dietlind Zohlhöfer-Momm), Zentralklinikum Augsburg (Wolfgang von Scheidt, Philip Raake), Gesundheitszentrum Bitterfeld/Wolfen, Bitterfeld (Peter Lanzer, Axel Tamke), Allgemeines Krankenhaus, Celle (Wolfram Terres, Eberhard Schulz), St. Marienhospital, Vechta (Christian Zellerhoff, Reinhard K. Klocke, Achim Gutersohn), Klinikum Kirchheim-Nürtingen (Martin Eberhard Beyer, Thorsten Beck, Martin Beyer), Klinikum Ingolstadt (Conrad Pfafferott, Karlheinz Seidl, Blerim Luani), Klinikum Wolfsburg (Rolf Engberding, Claus Fleischmann, Marco R. Schroeter), Philippusstift Krankenhaus, Essen (Birgit Hailer), Dr.-Horst-Schmidt-Kliniken, Wiesbaden (Martin Sigmund, Wolfgang Ferrari), Klinikum Landshut (Stefan Holmer), Kreiskrankenhaus Hameln (Hubert Topp, Daniel Griese), St. Josefs-Hospital, Wiesbaden (Wolfgang Kasper, Joachim Ehrlich), Stiftungsklinikum Mittelrhein, Koblenz (Norbert Kaul, Dietmar Burkhardt), Klinikum Saarbrücken gGmbH (Günter Görge, Florian Custodis), Marienhospital, Euskirchen (Heinz Kahles, Carsten Zobel), Diakonie Krankenhaus Bad Kreuznach (Mathias Elsner, Nevin Yilmaz-Zeytin), Klinikum Itzehoe (Michael F. D. Kentsch, Christian Eickholt), Städt. Kliniken FfM/Hoechst (Semi Sen, Christoph Kadel, Ulrich Hink), Klinikum Hildesheim (Jürgen Tebbenjohanns), Klinikum Offenbach (Harald Klepzig, Timm Bauer), Klinikum Aschaffenburg (Rainer Uebis, Mark Rosenberg), DRK-Kliniken Berlin-Westend (Ralph Schöller, Christian Opitz), Christliches Krankenhaus, Quakenbrück (Bettina Götting, Fadi Al Abdullah), Kreiskrankenhaus Alt/Neuötting (Walter Notheis), Klinikum Salzgitter (Andreas Strauss, Wolfgang Andreas Schöbel), St. Elisabeth-Krankenhaus, Bad Kissingen (Rainer Schamberger, Oliver Zagorski), Klinikum Kempten-Oberallgäu (Friedrich Seidel, Jan Torzewski), Kreisklinik Dachau (Michael A. J. Weber, Bernhard Witzenbichler), DRK-Krankenhaus Berlin-Köpenick (Hans F. Vöhringer, Iskandar Atmowihardjo), Verbundkrankenhaus Bernkastel-Wittlich (Thomas Zimmer, Brigitta Gestrich, Christian Bruch), Krankenhaus Siegburg GmbH (Eberhard Grube, Marc M. Vorpahl), Klinikum Hellersdorf, Berlin (Steffen Behrens, Jens-Uwe Röhnisch), Klinikum München Pasing (Christopher Reithmann, Sebastian Kufner), Klinikum Lippe-Detmold (Ulrich Tebbe, Stephan Gielen), Klinik Pirna GmbH (Christoph Axthelm, Steffen Schön, Holger Thiele), St. Elisabethkrankenhaus, Dorsten (Jan Bernd Böckenförde).

References

1. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119-177. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393

2. Thiele H, Akin I, Sandri M, et al; CULPRIT-SHOCK Investigators. One-year outcomes after PCI strategies in cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(18):1699-1710. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808788

3. Zeymer U, Hochadel M, Thiele H, et al. Immediate multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention versus culprit lesion intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: results of the ALKK-PCI registry. EuroIntervention. 2015;11(3):280-285. doi:10.4244/EIJY14M08_04

4. Harjola VP, Lassus J, Sionis A, et al; GREAT network. Clinical picture and risk prediction of short-term mortality in cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(5):501-509. doi:10.1002/ejhf.260

5. Goldberg RJ, Spencer FA, Gore JM, Lessard D, Yarzebski J. Thirty-year trends (1975 to 2005) in the magnitude of, management of, and hospital death rates associated with cardiogenic shock in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Circulation. 2009;119(9):1211-1219. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.814947

6. Zeymer U, Zahn R, Hochadel M, et al. Incications and complications of invasive diagnostic procedures and percutaneous coronary interventions in the year 2003. Results of the quality control registry of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitende Kardiologische Krankenhausarzte (ALKK). Z Kardiol. 2005;94(6):392-398. doi:10.1007/s00392-005-0233-2

7. Vogt A, Bonzel T, Harmjanz D, et al. PTCA registry of German community hospitals. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Leitender Kardiologischer Krankenhausärzte (ALKK) study group. Eur Heart J. 1997;18(7):1110-1114. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015405

8. Khan MZ, Munir MB, Khan MU, et al. Trends, outcomes, and predictors of revascularization in cardiogenic shock. Am J Cardiol. 2020;125(3):328-335. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.10.040

9. Bangalore S, Gupta N, Guo Y, et al. Outcomes with invasive vs conservative management of cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2015;128(6):601-608. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.12.009

10. Backhaus T, Fach A, Schmucker J, et al. Management and predictors of outcome in unselected patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: results from the Bremen STEMI registry. Clin Res Cardiol. 2018;107(5):371-379. doi:10.1007/s00392-017-1192-0

11. Zeymer U, Hochadel M, Karcher AK, et al; ALKK Study Group. Procedural success rates and mortality in elderly patients with percutaneous coronary intervention for cardiogenic shock. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12(18):1853-1859. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2019.04.027

12. Thiele H, Akin I, Sandri M, et al; CULPRIT-SHOCK Investigators. PCI strategies in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(25):2419-2432. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1710261

13. Webb JG, Lowe AM, Sanborn TA, et al; SHOCK Investigators. Percutaneous coronary intervention for cardiogenic shock in the SHOCK trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(8):1380-1386. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(03)01050-7

14. Thiele H, Zeymer U, Thelemann N, et al; IABP-SHOCK II Trial (Intraaortic Balloon Pump in Cardiogenic Shock II) Investigators; IABP-SHOCK II Investigators. Intraaortic balloon pump in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: long-term 6-year outcome of the randomized IABP-SHOCK II trial. Circulation. 2019;139(3):395-403. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038201