Electrophysiology Lab Efficiency Simulation: A Comparison Between Novel Dual-Energy Lattice-Tip and Conventional Contact-Force Sensing Radiofrequency Ablation Systems

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Objectives. Increasing atrial fibrillation (AF) disease-related healthcare burden, coupled with positive evidence on catheter ablation for AF, has led to pressure on hospital procedure efficiency. Medtronic’s Sphere-9 system (a novel lattice-tip dual-energy pulsed field and radiofrequency [RF] ablation catheter) demonstrated non-inferiority in effectiveness and superiority in procedural times compared with a contact-force sensing RF catheter (ThermoCool SmartTouch SF [STSF]). This analysis evaluated the impact of procedural efficiencies on electrophysiology (EP) lab utilization.

Methods. A discrete event simulation model evaluated EP lab efficiency using procedure times from the SPHERE Per-AF trial for pulmonary vein isolation-only cases and those with additional ablation lesion sets. Lab day ran from 7 am to 7 pm with 1 hour needed to perform an additional non-ablation EP case, and same-day discharge was allowed for cases ending by 5 pm.

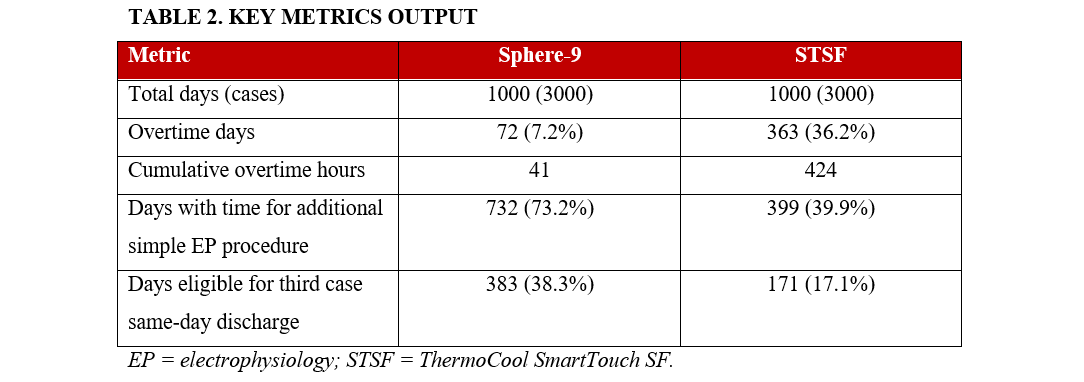

Results. Analysis included 211 patients in the Sphere-9 arm and 207 in the STSF arm. Procedure times were 100.8 ± 31 minutes for Sphere-9 and 125.9 ± 49 for STSF. Sphere-9 resulted in more than a 10-fold reduction in cumulative overtime hours (41 hours for Sphere-9 vs 424 for STSF). Overtime occurred on 7% of lab days with Sphere-9 and 36% with STSF. Additionally, 73% of Sphere-9 lab days allowed for 1 additional non-ablation EP case compared with 40% of STSF lab days. Finally, 38% of Sphere-9 lab days allowed for same-day discharge for the third case compared with 17% of STSF lab days.

Conclusions. In patients with persistent AF, the Sphere-9 system was more efficient and predictable compared with STSF, leading to significant improvements in EP lab efficiency.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) affects an estimated 37 million people worldwide.1 AF incidence continues to increase globally because of an increase in the aging population and in individuals (regardless of age) with AF risk factors.2 Increased evidence showing the safety and efficacy of catheter ablation therapy for AF management3 has led to increased demand for AF ablation procedures, which has surpassed hospital capacity and consequently increased wait times to receive the procedure.4 Thus, in addition to enhanced safety and efficacy for catheter ablation, there is a need for improved procedural efficiency.

Catheter ablation is considered beneficial and recommended in symptomatic patients with recurrent paroxysmal or persistent AF that is resistant or intolerant to previous treatment with at least 1 Class I or III antiarrhythmic drug.3 Ablation for persistent AF has previously been limited to radiofrequency (RF) or cryoballoon. Recently, the Medtronic Sphere-9 system, an “all-in-one” catheter incorporating navigation with high-density (HD) mapping and diagnostics with the capability of dual-energy ablation in pulsed field (PF) and radiofrequency (RF), has been approved for the treatment of persistent AF. The SPHERE Per-AF trial randomized patients with persistent AF to ablation with a wide-footprint, lattice-tip pulsed field (PF) and radiofrequency (RF) mapping and ablation catheter (Sphere-9 catheter and the Affera Mapping and Ablation System) vs a control system, which included a conventional contact-force sensing RF catheter (ThermoCool SmartTouch SF [STSF] with a CARTO mapping and navigation system). The Sphere-9 arm demonstrated non-inferiority in both primary effectiveness and safety. In addition, Sphere-9 had significantly shorter procedural times compared with the STSF.5 This analysis evaluated the impact of these procedural efficiencies on hospital resources and electrophysiology (EP) lab utilization.

Methods

Study design

The SPHERE Per-AF trial has previously been described in detail.5 In brief, this pivotal, multicenter, randomized, single-blind controlled trial was designed to test non-inferiority endpoints of safety, effectiveness, and efficiency when comparing Sphere-9 catheter and the Affera Mapping and Ablation System to the STSF catheter with a CARTO mapping and navigation system. The SPHERE Per-AF received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and from the institutional review board at each participating center and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for the study described in the manuscript and to the publication of their data.

Procedure times

Skin-to-skin procedure times (the duration from initial venous access to removal of the last sheath) from the SPHERE Per-AF trial for pulmonary vein isolation (PVI)-only cases and those with additional ablation lesion sets were used for this data analysis.5 Non-procedure times were based on data from the STOP Persistent AF trial6 because the SPHERE Per-AF trial did not collect non-procedure times. The assumption was that non-procedure times are not dependent on catheter choice. Lab occupancy times (the time from the patient entering the EP lab to when they exited the lab) were derived by adding the skin-to-skin procedure times to the non-procedure times. In the SPHERE Per-AF trial, vascular access site complications occurred in 5 patients in the Sphere-9 arm and 9 patients in the STSF arm.5 While detailed breakdowns of specific complications were not explicitly modeled, these complications were included in the SPHERE Per-AF trial data, which served as the basis for the model. Therefore, the impact of such complications on EP lab occupancy time is reflected in the results.

Discrete event simulation model

A discrete event simulation (DES) model was used to evaluate EP lab efficiency using the derived lab occupancy times. DES models are suited to predict the behavior of complex real-world operational systems by representing how individual resources impact events that occur over time. DES models have been applied to numerous efficiency-related analyses in health care settings.7,8

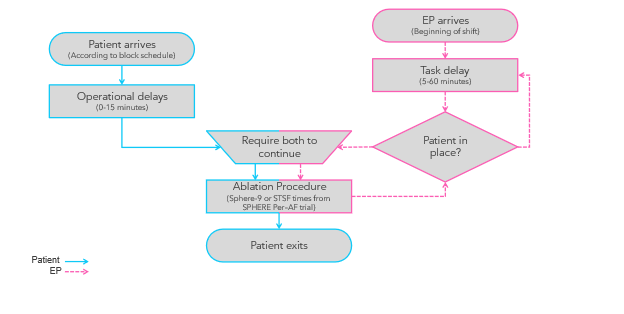

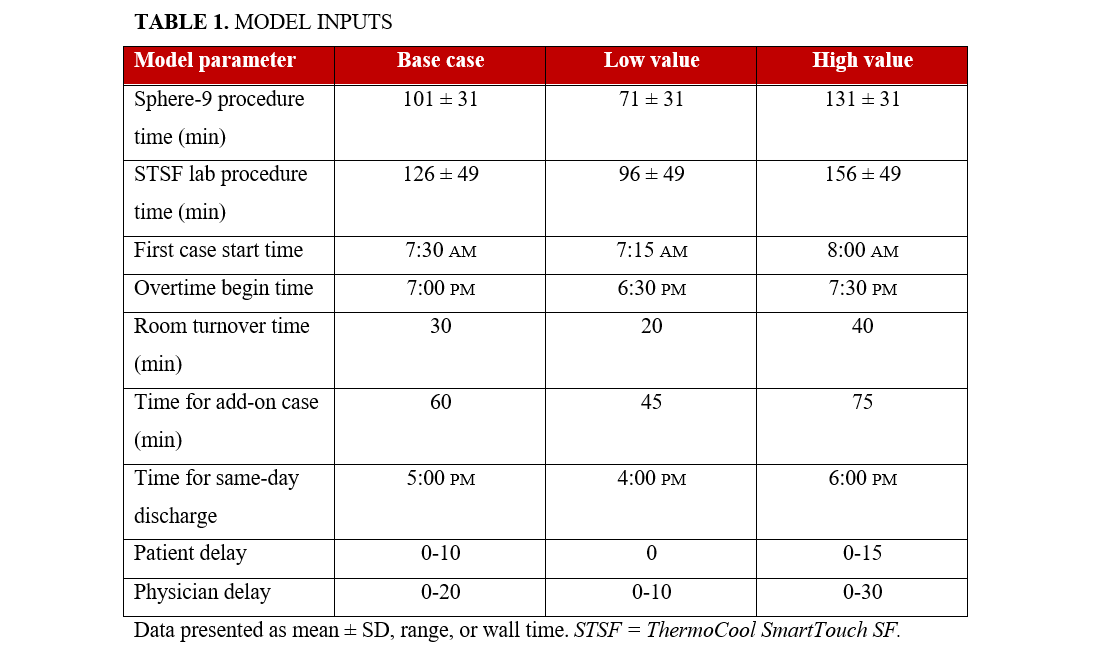

This analysis uses an adaptation of a published model.9 The model (Figure 1) accounts for the availability and activities of key participants and resources such as physicians, support staff, patients, and the EP lab, all of which play a role in influencing lab occupancy times. Delays in ablation procedures were due to both physicians and patients, with delay times drawn from specified distributions (Table 1). In the DES model, an ablation procedure could only start when both the physician and patient were present, with the total procedure duration based on a probability distribution of lab occupancy times. The model was simulated across 1000 days to capture daily fluctuations. We assessed the percentage of days that resulted in (1) staff overtime, (2) sufficient extra time to perform 1 additional straightforward EP procedure (like a pacemaker implant or defibrillator replacement), and (3) the third ablation case of the day ending early enough to allow same-day discharge from the hospital. The DES model was conducted using SIMUL8 professional software (version 31.0; SIMUL8 Corporation).

DES model inputs

The model assumed that 3 ablation procedures could be completed in a single day, with specific days dedicated to ablation procedures in the EP lab. The lab occupancy times were complemented by additional EP lab management details (such as time between procedures and shift schedules) collected through surveys of EP staff. Operational delays were informed by qualitative research with study sites and included (1) a fixed 30-minute turnover time for the EP lab, (2) a 0 to 10-minute delay range for patients, and (3) a 0 to 20-minute delay range for physicians. It was assumed that the first procedure of the day would start at 7:30 am, with subsequent procedures beginning after accounting for the EP lab turnover time. Same-day discharge was possible for cases that ended on or before 5:00 PM, and overtime was defined to start at 7:00 pm. All model input details are presented in Table 1.

Model validation, scenario, and sensitivity analysis

Model validation involved comparing summary statistics of the lab occupancy times from the simulation with those recorded in the SPHERE Per-AF trial5 and the STOP Persistent AF trial.6 Additionally, a deterministic sensitivity analysis was carried out by individually adjusting each model input value to both the "high" and "low" extremes of the range, representing the boundary scenarios on either side of the base-case scenario (Table 1). A probabilistic sensitivity analysis was not conducted because the DES is, by definition, stochastic.

Statistics

Procedure time data from the SPHERE Per-AF trial5 were analyzed and presented as mean values, SDs, and the 10th and 90th percentile ranges. The model's key outputs included cumulative overtime hours, percentage of days that resulted in overtime, days with time for additional simple EP procedures, and same-day discharge for the third case of the day. Variability in lab occupancy time was characterized by using best-fit distributions. Excel (Microsoft Corporation) and Spotfire Analyst (version 12.0.4; Tibco) were used to create all graphs, plots, and tables.

Results

EP lab occupancy time distributions

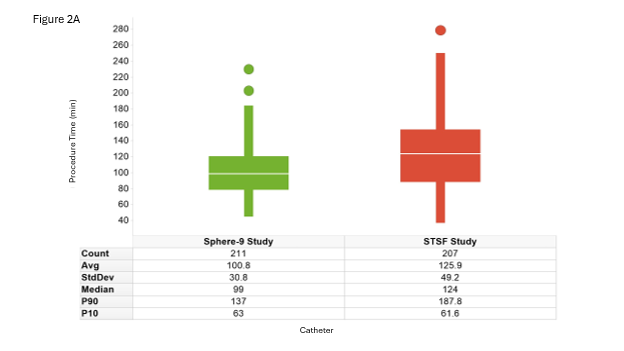

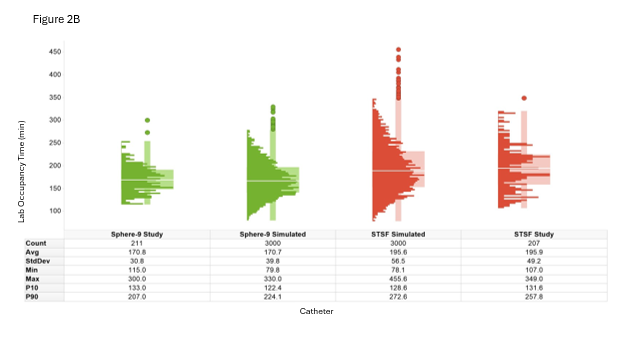

This dataset was based on procedure data from patients treated with Sphere-9 (n = 211) and STSF (n = 207) therapies. The baseline characteristics, treatment specifics, and clinical outcomes by treatment arm have been previously published.5 Across the full cohort, the skin-to-skin procedure time was 100.8 ± 31 minutes for Sphere-9 and 125.9 ± 49 minutes for STSF (Figure 2A). The detailed procedure times by treatment arm were modeled using Weibull distributions for input into the DES model.

EP lab efficiency outcomes

Ablation procedures representing Sphere-9 and STSF therapies were simulated over 1000 EP lab days, creating data on 3000 ablation procedures per therapy. Sphere-9 resulted in 72 (7.2%) simulated days of overtime vs 362 (36.2%) for STSF. The cumulative overtime over the full simulation was 41 hours for Sphere-9 and 424 hours for STSF. Cases were completed early enough to permit an additional simple EP procedure without incurring overtime in 732 (73.2%) days for Sphere-9 and 399 (39.9%) days for STSF. Finally, the third case of the day was eligible for same-day discharge in 383 (38.3%) days for Sphere-9 vs 171 (17.1%) days for STSF (Table 2).

Validation, scenario, and sensitivity analyses

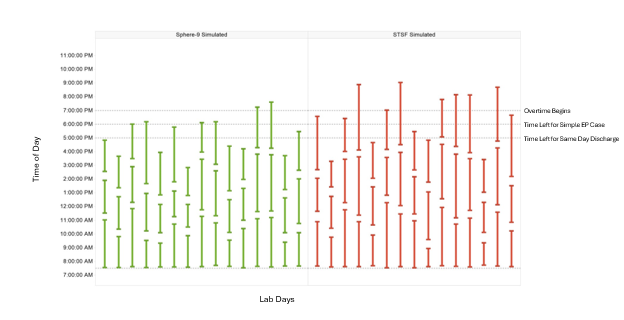

To validate the model, the distribution of EP lab occupancy times generated by the model was compared to the actual lab occupancy time distribution observed in the study, stratified by treatment. After simulating 1000 days, the average lab occupancy time closely matched the expected mean from the SPHERE Per-AF5 and STOP Persistent AF trials,6 with a margin of error within 3% and a CI of 95% (Figure 2B). Figure 3 illustrates representative simulated case lab occupancy times within the context of a complete EP lab day.

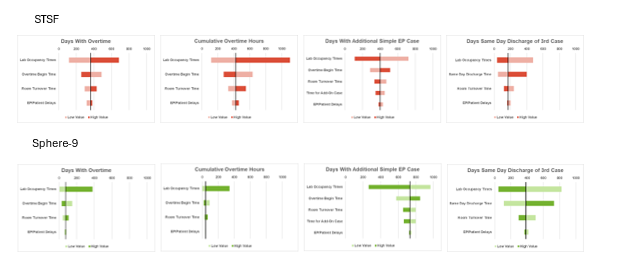

Figure 4 presents the results of the sensitivity analysis, focusing on overtime days, cumulative overtime, days with sufficient time for 1 additional simple EP case, or days allowing same-day discharge for third cases. The DES model showed the greatest sensitivity to variations in lab occupancy time and the overall length of the lab day (overtime start time and same day discharge time). Increases in lab occupancy time, shorter lab days, or extended room turnover times led to more frequent overtime, higher cumulative overtime hours, and fewer days available for additional simple EP procedures or same-day discharge of a third case.

Discussion

In patients with persistent AF, the Sphere-9 system was more efficient and predictable compared with the STSF. These efficiencies led to significant improvements in EP lab efficiency, which included a reduction in cumulative overtime hours, more days where overtime is avoided, more opportunities for additional non-ablation cases, and increased same-day discharge. In brief, Sphere-9 resulted in more than a 10-fold reduction in cumulative overtime hours; overtime occurred on only 7% of lab days with Sphere-9 vs 36% with STSF. Additionally, 73% of Sphere-9 lab days allowed for 1 additional non-ablation EP case without requiring overtime compared with 40% for STSF. Lastly, 38% of Sphere-9 lab days allowed for same-day discharge for the third case without requiring staff overtime compared with 17% of STSF lab days. The efficiency metrics were most sensitive to changes in lab occupancy time and end-of-day times (overtime start time).

The skin-to-skin procedure time for Sphere-9 was 100.8 minutes vs 125.9 minutes for STSF. Of note, in the Sphere-9 arm, there was a higher percentage of patients who received additional ablation lesions beyond PVI (95.8% for Sphere-9 and 85.6% for STSF); thus, more ablation in less time.5 There are several mechanisms that contribute to Sphere-9’s efficiency. Sphere-9’s lattice tip enhances tissue contact and stability, which reduces the likelihood of catheter spillage and allows for increased contact pressure without causing significant tissue trauma, thus promoting effective and efficient lesion formation.10 Furthermore, the larger footprint catheter enables the creation of substantial lesions with fewer and shorter energy deliveries.10 The streamlined and automated mapping system reduces the potential for user errors and ensures that essential features are readily accessible, thereby enhancing procedural efficiency. In addition, the integration of the pacing system within the mapping platform eliminates the need to switch between systems, allowing for efficient data collection.11 Lastly, the all-in-one catheter feature, which allows for pacing, diagnostics, mapping, and dual-energy ablation without exchanging diagnostic and ablation catheters or overlaying therapeutic and diagnostic catheters to identified areas of interest, creates efficiencies in procedural handling.

This discrete event simulation analysis demonstrated that it is possible to consistently perform 3 ablation cases per day using Sphere-9, while performing 3 ablation cases with STSF was associated with significant staff overtime. Of note, Sphere-9 is a novel technology, while STSF has been in use for almost 5 years (and the predicate ThermoCool catheter had been in use for more than 15 years). In addition, Sphere-9 has a rapid operator learning curve of 10 procedures, as shown in a post hoc analysis of the SPHERE Per-AF trial.12 Increased operator experience with Sphere-9 is expected to lead to even more efficiency and the potential ability to perform more than 3 ablation cases in a day. Indeed, increased operator experience and technological advancement of the cryoballoon led to reduced ablation procedure times, supporting the feasibility of moving from 2 to 3 ablation cases per day.9 The efficiency improvements associated with the cryoballoon were robust enough to enable meaningful efficiency improvements across multiple diverse healthcare systems.13-15

The ability to perform more AF ablation cases in a day is essential to reducing patient wait times. Rapid increase in AF burden16 coupled with mounting evidence showing improved efficacy of catheter ablation in AF treatment3,17 has led to increased demand for ablation. The demand has surpassed EP labs capacity, leading to long patient wait times. For example, the median wait time for patients who received catheter ablation in Ontario, Canada between 2016 and 2020 was 218 days (IQR, 112-363).4 These delays in receiving ablation are associated with significant adverse outcomes including higher risk of AF recurrence post-ablation;18 thus, there is a need to reduce the wait times. This is especially important in persistent AF populations who typically have poor outcomes and require complex procedures.19,20 Being able to safely perform more procedures with the available resources is one way for hospitals to optimally utilize their resources.

Same-day discharge is another potential way to maximize hospital resource utilization and potentially reduce the procedural wait times. In our analysis, Sphere-9 increased the probability of same-day discharge compared with STSF. Same-day discharge after an AF procedure has been found to be safe and appropriate for some patients.3 Traditional RF procedures have a postoperative tendency for volume overload, chest discomfort, and post-anesthesia symptoms. Further investigation is needed to determine whether use of PFA reduces these patient symptoms and how it impacts the probability of same-day discharge.

Lastly, Sphere-9 was associated with a significant reduction in overtime compared with STSF. The reduced overtime and increased predictability associated with Sphere-9 may have positive benefits on hospital staff by reducing burnout, a growing phenomenon among healthcare workers.21,22 It may also have positive benefits on patients because of more predictability in scheduling times for procedures and reduction in medical care errors associated with overtime while allowing for same-day discharge when it is requested.23

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. This analysis was based on simulation modeling rather than real-world experience; however, the model was designed with feedback from physicians and EP lab managers and its inputs were carefully calibrated to match the procedure data from the study. Granular information on specific complications was not explicitly modeled, but those complications were present in the study data on which the model was based, so the impact of those complications is reflected in the results. It is possible that some aspects of complication management that happened outside the EP lab were not fully captured in our manuscript. However, the primary aim of the paper was to model the impact of procedural efficiencies specifically within the EP lab, which we considered the key limited resource. The study was based primarily on patients in the US healthcare system, which may limit global generalizability; however, EP lab procedures are reasonably standardized through guidelines and experience sharing at international conferences. Our analysis excluded 2 sites that did not allow secondary use of the data, thus the slight discrepancy in procedure times between our analysis and the published SPHERE Per-AF trial results.5 However, only 2 patients were excluded: 1 from the Sphere-9 arm and 1 from the STSF arm. The SPHERE Per-AF trial5 did not collect non-procedure times; thus, we used non-procedure time from the STOP Persistent AF trial6 in order to calculate lab occupancy time. However, both trials only had persistent patients, and the assumption was that non-procedure times are not dependent on catheter choice. The lab-operating parameters for different centers will vary from our assumptions, but they represent typical values and the results remained directionally consistent when these assumptions were varied in the sensitivity analysis. No attempt was made to model costs, and difference in catheter/tool/supply costs could vary between arms. There were differences in the number of extra lesions between the arms in the study, with more complex additional lesions being completed by the Sphere-9 arm.

Conclusions

Sphere-9, which demonstrated non-inferiority for the primary effectiveness and safety endpoints, was more predictable and efficient than STSF, leading to significant improvements in EP lab efficiency. These improvements from the simulation based on data from the SPHERE Per-AF trial included reduction in cumulative overtime hours, more days where overtime is avoided, more opportunities for additional non-ablation cases, and increased same-day discharges. These efficiencies, coupled with the demonstrated safety and efficacy, can help increase hospital capacity to safely cater to the growing population of patients with persistent AF.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Stavros E. Mountantonakis, MD, MBA1; Elad Anter, MD, FACC2; Jerry Marschke, MS3; Waruiru Mburu, PhD4; Reece Holbrook, MBA4; Hae W. Lim, PhD4; Tyler L. Taigen, MD5; on behalf of the SPHERE Per-AF Investigators

From 1Northwell Cardiovascular Institute, New Hyde Park, New York; 2Shamir Medical Center, Be'er Ya'Akov, Israel; 3PeaceHealth, St. Joseph Medical Center, Bellingham, Washington; 4Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota; 5Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to acknowledge Shufeng Liu and Fred Kueffer for providing access to data from the SPHERE Per-AF trial and Victoria Low for reviewing the manuscript.

Disclosures: Dr Mountantonakis has received research grants and honoraria from Medtronic. Dr Anter is a consultant to, and has received equity from Affera-Medtronic; serves in consulting and advisory capacities for Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, and Abbott Medical, unrelated to this manuscript; and has received research grants from Biosense Webster and Medtronic. Dr Mburu, Mr Holbrook, and Dr Lim are employees of Medtronic. Dr Taigen has served as a consultant for Biosense Webster and Medtronic. Dr Marschke reports no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Funding: This study was sponsored by Medtronic.

Clinical trial registration: Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT05120193

Address for correspondence: Stavros E. Mountantonakis, MD, MBA, 100 E 77th St 2 Lachman, New York, NY 10075, USA. Email: Smountanto@northwell.edu

References

1. Lippi G, Sanchis-Gomar F, Cervellin G. Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: an increasing epidemic and public health challenge. Int J Stroke. 2021;16(2):217-221. doi:10.1177/1747493019897870

2. Williams BA, Honushefsky AM, Berger PB. Temporal trends in the incidence, prevalence, and survival of patients with atrial fibrillation from 2004 to 2016. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120(11):1961-1965. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.08.014

3. Tzeis S, Gerstenfeld EP, Kalman J, et al. 2024 European Heart Rhythm Association/Heart Rhythm Society/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2024;26(4):euae043. doi:10.1093/europace/euae043

4. Qeska D, Singh SM, Qiu F, et al. Variation and clinical consequences of wait-times for atrial fibrillation ablation: population level study in Ontario, Canada. Europace. 2023;25(5):euad074. doi:10.1093/europace/euad074

5. Anter E, Mansour M, Nair DG, et al; SPHERE PER-AF Investigators. Dual-energy lattice-tip ablation system for persistent atrial fibrillation: a randomized trial. Nat Med. 2024;30(8):2303-2310. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03022-6

6. Su WW, Reddy VY, Bhasin K, et al; STOP Persistent AF Investigators. Cryoballoon ablation of pulmonary veins for persistent atrial fibrillation: results from the multicenter STOP Persistent AF trial. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17(11):1841-1847. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.06.020

7. Caro JJ, Ward A, Deniz HB, O'Brien JA, Ehreth JL. Cost-benefit analysis of preventing sudden cardiac deaths with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator versus amiodarone. Value Health. 2007;10(1):13-22. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00140.x

8. Laker LF, Froehle CM, Lindsell CJ, Ward MJ. The flex track: flexible partitioning between low- and high-acuity areas of an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64(6):591-603. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.05.031

9. Kowalski M, Su WW, Holbrook R, Sale A, Braegelmann KM, Calkins H; STOPPersistent AF Investigators. Impact of cryoballoon ablation on electrophysiology lab efficiency during the treatment of patients with persistent atrial fibrillation: a subanalysis of the STOP Persistent AF study. J Invasive Cardiol. 2021;33(7):E522-E530. doi:10.25270/jic/20.00620

10. Reddy VY, Anter E, Rackauskas G, et al. Lattice-tip focal ablation catheter that toggles between radiofrequency and pulsed field energy to treat atrial fibrillation: a first-in-human trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020;13(6):e008718. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.120.008718

11. Reddy VY, Anter E, Peichl P, et al. First-in-human clinical series of a novel conformable large-lattice pulsed field ablation catheter for pulmonary vein isolation. Europace. 2024;26(4):euae090. doi:10.1093/europace/euae090

12. Kiehl EL, Mountantonakis SE, Mansour MC, et al; SPHERE Per-AF Investigators. Operator learning curve with a novel dual-energy lattice-tip ablation system. Heart Rhythm. 2025:S1547-5271(25)00120-1. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2025.02.006

13. Földesi C, Kojić D, Sudzinova A, et al. Electrophysiology lab efficiency using cryoballoon for pulmonary vein isolation in central and eastern Europe: a sub-analysis of the cryo global registry study. Cardiol J. 2024;31(5):656-664. doi:10.5603/cj.98292

14. Pérez-Silva A, Isa-Param R, Agudelo-Uribe JF, et al. Electrophysiology lab efficiency using cryoballoon for pulmonary vein isolation in Latin America: A sub-analysis of the cryo global registry study. Medwave. 2024;24(8):e2918. doi:10.5867/medwave.2024.08.2918

15. Metzner A, Straube F, Tilz RR, et al; FREEZE Cohort Study Investigators. Electrophysiology lab efficiency comparison between cryoballoon and point-by-point radiofrequency ablation: a German sub-analysis of the FREEZE cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023;23(1):8. doi:10.1186/s12872-022-03015-8

16. Ma Q, Zhu J, Zheng P, et al. Global burden of atrial fibrillation/flutter: trends from 1990 to 2019 and projections until 2044. Heliyon. 2024;10(2):e24052. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24052

17. Rottner L, Bellmann B, Lin T, et al. Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: state of the art and future perspectives. Cardiol Ther. 2020;9(1):45-58. doi:10.1007/s40119-019-00158-2

18. Chew DS, Black-Maier E, Loring Z, et al. Diagnosis-to-ablation time and recurrence of atrial fibrillation following catheter ablation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020;13(4):e008128. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.119.008128

19. Mansour M, Calkins H, Osorio J, et al. Persistent atrial fibrillation ablation with contact force-sensing catheter: the prospective multicenter PRECEPT trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2020;6(8):958-969. doi:10.1016/j.jacep.2020.04.024

20. Verma A, Haines DE, Boersma LV, et al; PULSED AF Investigators. Pulsed field ablation for the treatment of atrial fibrillation: PULSED AF pivotal trial. Circulation. 2023;147(19):1422-1432. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.063988

21. De Hert S. Burnout in healthcare workers: prevalence, impact and preventative strategies. Local Reg Anesth. 2020;13:171-183. doi:10.2147/LRA.S240564

22. Nigam JAS, Barker RM, Cunningham TR, Swanson NG, Chosewood LC. Vital signs: health worker-perceived working conditions and symptoms of poor mental health - quality of worklife survey, United States, 2018-2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(44):1197-1205. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7244e1

23. Kwak SK, Ahn JS, Kim YH. The association of job stress, quality of sleep, and the experience of near-miss errors among nurses in general hospitals. Healthcare (Basel). 2024;12(6):699. doi:10.3390/healthcare12060699