Clinical, Procedural, and Follow-up Outcomes of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention-Related Stroke: Insight From the PROGRESS-COMPLICATIONS Registry

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Stroke is an infrequent but potentially severe complication of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Methods. The authors describe the clinical features, angiographic characteristics, and procedural and follow-up outcomes of PCI-related stroke in the PROGRESS-COMPLICATIONS registry.

Results. Of 22 503 patients who underwent PCI at 2 tertiary care centers between 2016 and 2023, 157 (0.7%) had PCI-related stroke: 10 (6.4%) had hemorrhagic stroke while 147 (93.6%) had ischemic stroke. The mean age of the stroke patients was 70 ± 11 years; 63.1% were men, 25.2% had prior heart failure, 71.0% had diabetes mellitus, 85.4% had hypertension, and 36.6% had chronic kidney disease. Radial access was used in 39.5% of the patients; 31.1% of stroke patients presented with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), 49.7% with non-STEMI, and 14.6% with stable angina. The target lesions were complex: 47.1% were bifurcations, 63.7% had moderate to severe calcification, and 56.0% had thrombus. The mean minimum activated clotting time of the stroke patients was 214 (165, 245) seconds. Technical success was 93%. A mechanical circulatory support device was utilized in 31 (20%) of the patients, and 17 (10.8%) presented with cardiogenic shock. Hypotension during the procedure occurred in 36 patients (22.9%), bleeding occurred in 37 patients (23.6%), and in-hospital mortality was 13.7%. During a median follow-up of 32 months, 48.3% of the patients had follow-up major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and 24.5% died.

Conclusions. Stroke is an infrequent but severe complication of PCI, associated with high mortality and MACE. Most periprocedural strokes were ischemic.

Introduction

Stroke is a major complication of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with a reported incidence of 0.18% to 1.2%1,2 and higher incidence among patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS).3 Stroke after PCI has been associated with high morbidity and mortality.4 In addition, PCI-related stroke has been associated with higher long-term mortality, morbidity, and health care costs.5 Therefore, both prevention and prompt management of stroke are essential. However, research in this area remains limited. We examined the incidence and outcomes of periprocedural stroke at a tertiary center.

Methods

The Prospective Global Registry for the Study of Complications (PROGRESS-COMPLICATION) Registry (NCT05100940) includes data of 157 PCIs complicated by stroke among 22 503 PCIs performed at 2 tertiary PCI centers (Minneapolis Heart Institute, University of Washington). We examined the clinical features, angiographic characteristics, and procedural and follow-up outcomes of the patients with PCI-related stroke. The Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation hosted Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) electronic data capture tools, which were used to collect and manage study data.6 The institutional review board approved the study.

New-onset PCI-related stroke was confirmed through clinical evaluation and neuroimaging, including computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Ischemic stroke was defined as the acute onset of neurological deficits accompanied by newly identified ischemic lesions on neuroimaging.7 Hemorrhagic stroke was defined as the sudden onset of neurological symptoms in the presence of new hemorrhagic brain lesions.8 The date and time of stroke was extracted from hospital medical records.

Bifurcation lesions were defined in accordance with the Bifurcation Academic Research Consortium (Bif-ARC) criteria as coronary artery stenoses occurring adjacent to and/or involving the origin of a side branch (SB) with a diameter exceeding 2.0 mm.9

In the present registry, the target activated clotting time (ACT) during PCI procedures was generally greater than 250 seconds when unfractionated heparin was used, in line with current clinical practice guidelines.10 In cases where glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were administered, a target ACT of 200 to 250 seconds was typically pursued, whereas, in their absence, a range of 250 to 300 seconds was preferred.10 In more complex procedures, some operators aimed for higher ACT levels (up to 300-350 seconds), consistent with prior reports and procedural standards.11 In accordance with previous studies, ACT values of less than 200 seconds were classified as subtherapeutic, potentially reflecting inadequate anticoagulation during the procedure.12

Coronary calcification was assessed angiographically and classified as mild (focal calcific spots), moderate (calcification involving ≤50% of the reference vessel diameter), or severe (calcification involving >50% of the reference diameter). Proximal vessel tortuosity was considered moderate in the presence of at least 2 bends greater than 70° or a single bend greater than 90°, and severe if 2 bends exceeded 90° or if a single bend was greater than 120° within the target vessel.

Technical success was defined as successful revascularization with a residual diameter stenosis of less than 30% in the treated segment and restoration of Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) grade 3 antegrade flow. In-hospital major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) were defined as a composite of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, urgent repeat revascularization, or major bleeding.9 Procedural success was defined as an achievement of technical success without the occurrence of in-hospital MACE. Myocardial infarction was defined according to the Fourth Universal Definition of MI, specifically as type 4a MI.13 Follow-up MACE included the composite of death, MI, stroke, and target vessel revascularization (either by PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG]). Major bleeding was classified according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria as type 3 or higher.14

Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and compared using Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were reported as mean ± SD or median with IQR and compared using the independent-samples t-test for normally distributed data or the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test and normality plots. Trends over time were evaluated using the Mann-Kendall test for monotonic trend. Time-to-event outcomes were assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method, with comparisons made using the log-rank test. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software, version 4.4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). A 2-tailed P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

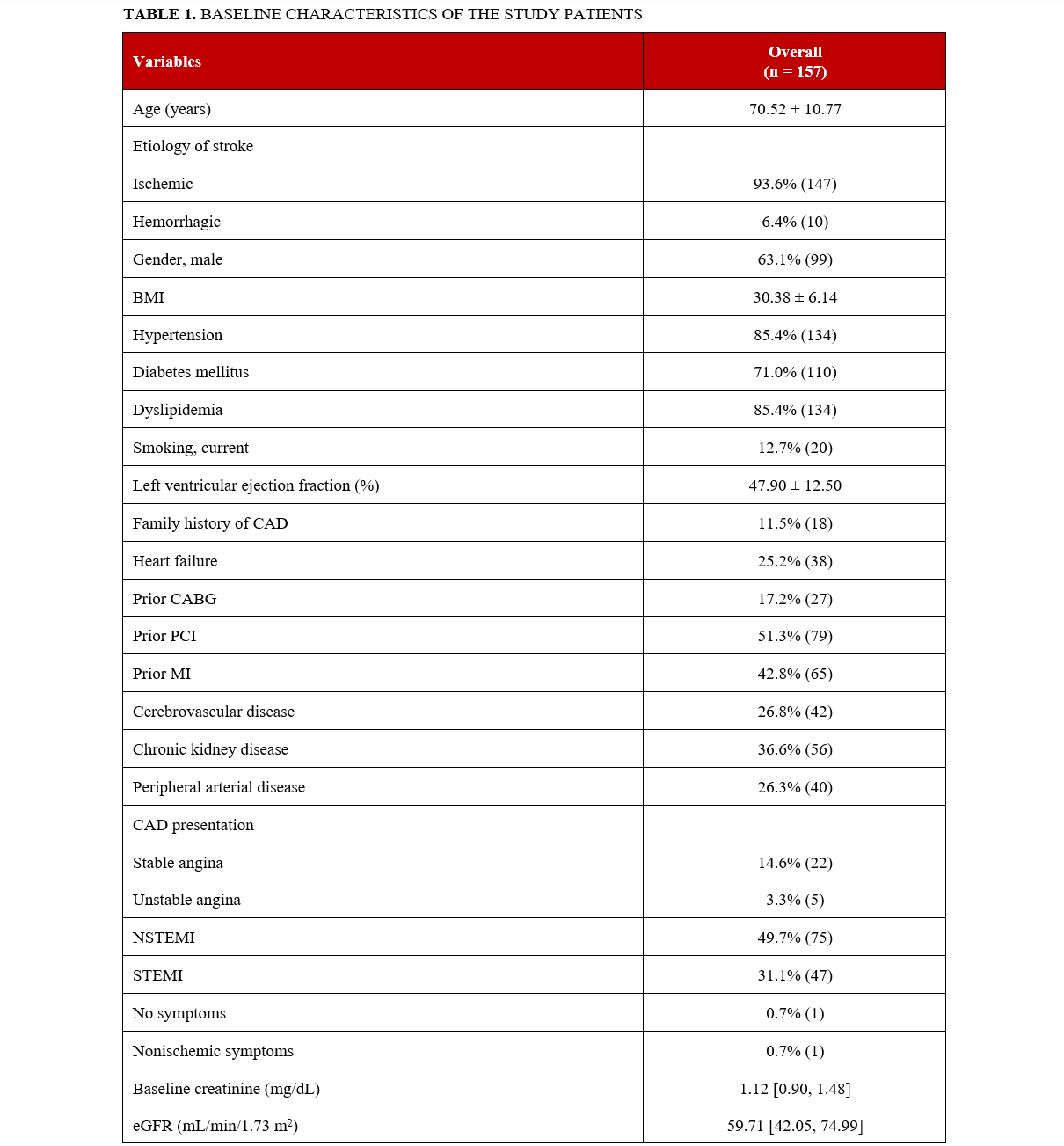

Of 22 503 patients who underwent PCI between 2016 and 2023, a total of 157 (0.7%) had PCI-related stroke: 10 (6.4%) had hemorrhagic stroke and 147 (93.6%) had ischemic stroke. The baseline characteristics of the stroke patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 70.5 ± 10.8 years, 63.1% (99) were men, 25.2% (38) had prior heart failure, 71% (110) had diabetes mellitus, 85.4% (134) had hypertension, 85.4% (134) had hyperlipidemia, 36.6% (56) had chronic kidney disease, 26.8% (42) had cerebrovascular disease, 26.3% (40) had peripheral arterial disease, and 12.7% (20) were current smokers. Stroke patients presented with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) in 31.1% (47) of cases, non-STEMI in 49.7% (75), unstable angina in 3.3% (5), and stable angina in 14.6% (22); 10.8% (17) presented with cardiogenic shock, 12.7% (20) with cardiac arrest, and 3.2% (5) with heart failure.

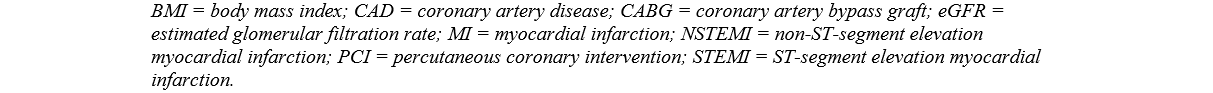

The baseline angiographic characteristics of the study patients are summarized in Table 2. The utilization of radial and femoral access was 39.5% (62) and 72.0% (113), respectively (11.4% [18] of the patients had both radial and femoral access). The left anterior descending artery (LAD) was the most common PCI target vessel in stroke patients. The prevalence of bifurcation lesions was 47.1% (74), 63.7% (100) had moderate to severe calcification, 27.7% (43) had moderate to severe proximal tortuosity, 14.9% (23) had in-stent restenosis (ISR), 6.6% (10) had stent thrombosis, and 56% (85) of the lesions were thrombus containing.

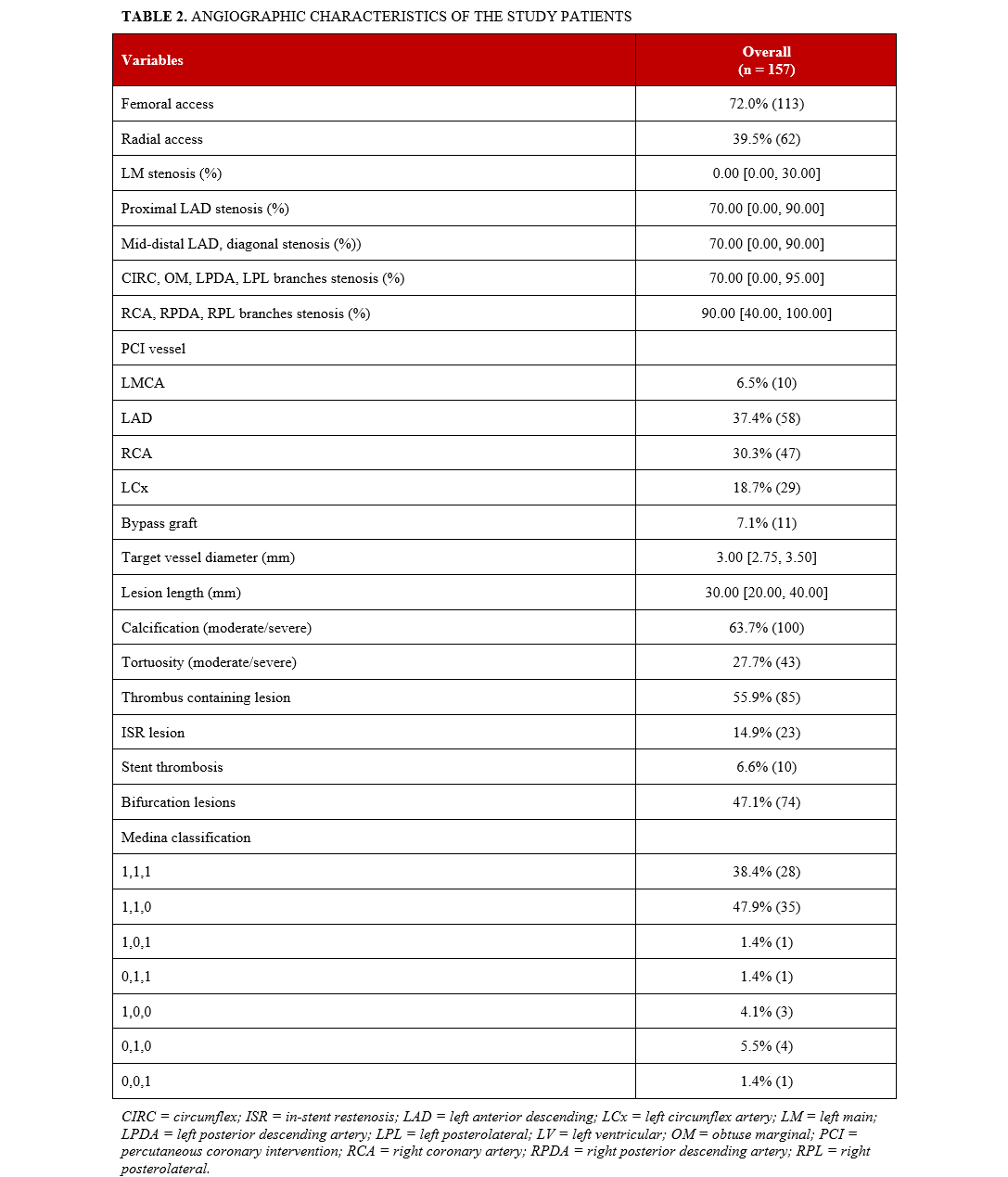

Equipment utilization is summarized in Table 3. The procedural anticoagulant used in all study patients was unfractionated heparin. The mean minimum ACT of the stroke patients was 214 (165, 245) seconds and the mean maximum ACT was 276 (243, 327) seconds. A mechanical circulatory support (MCS) device was used in 20% (31) of cases, with the most common device being an intraaortic balloon pump (IABP) (53.3% [16]). Among the 157 patients who experienced stroke, ACT values were available in 102 (64.9%) cases. Of these, 38 (37.3%) patients had ACT levels of less than 200 seconds, which were classified as subtherapeutic. The mean length of hospital stay of the stroke patients was 8 days. Among patients with available data, the median The National Institutes of Health stroke scale (NIHSS) score of PCI-related stroke patients was 5.00 (IQR, 2.00-10.00). Stroke severity was classified as mild in 48.5% (64) of patients, moderate in 35.6% (47), moderate to severe in 5.3% (7), and severe in 10.6% (14), according to NIHSS score. Regarding the timing of stroke, 15.1% (22) were intraprocedural, whereas most, 84.9% (124), occurred after completion of the PCI procedure.

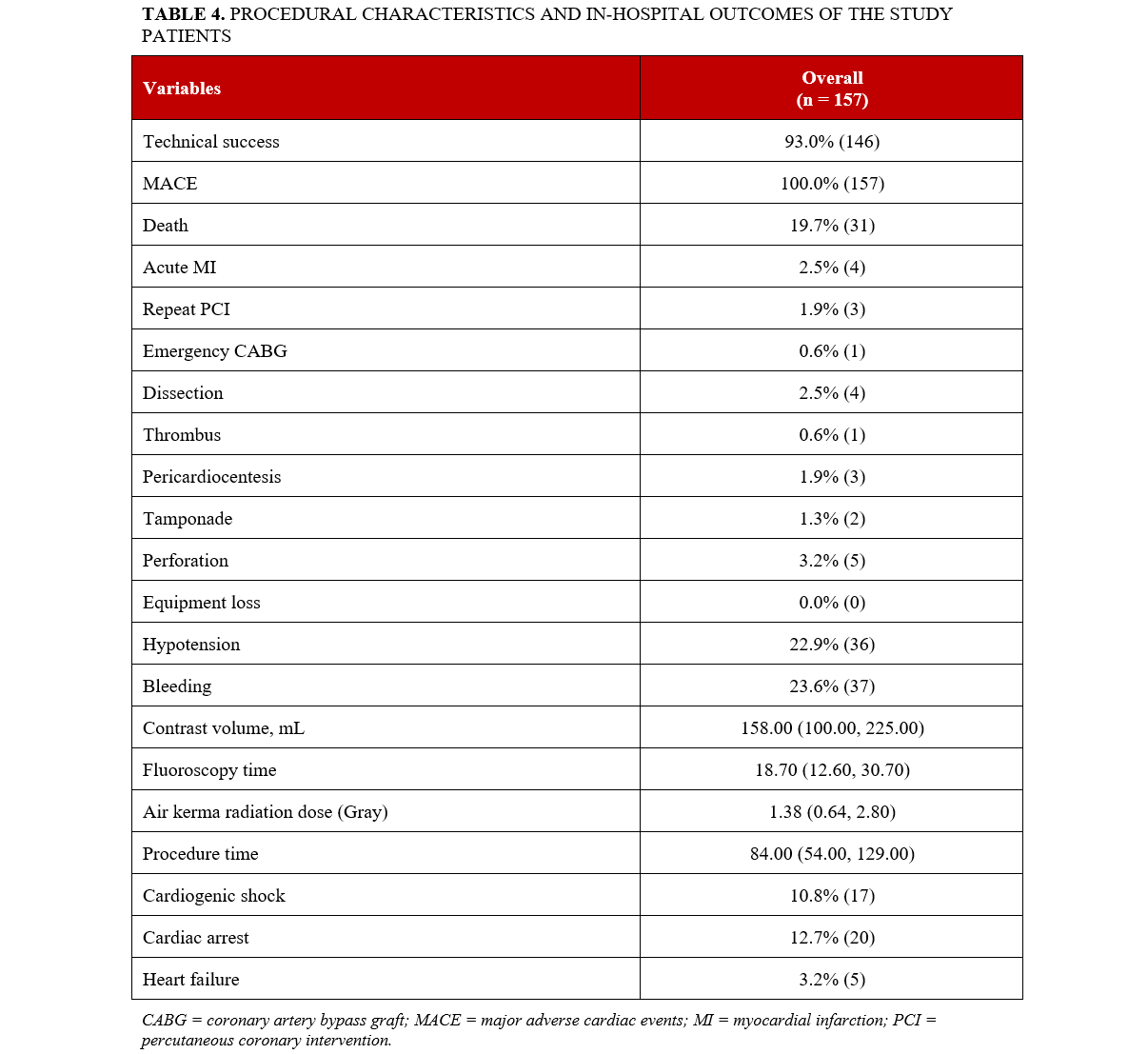

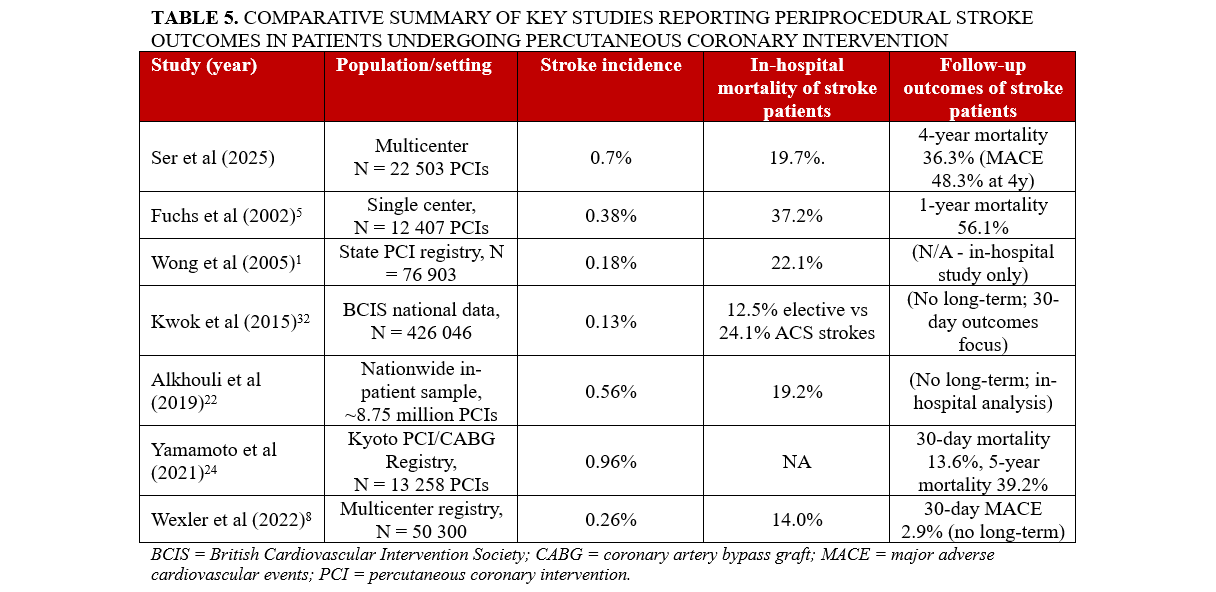

Procedural characteristics and in-hospital outcomes are summarized in Table 4. Technical success was 93% (146). Hypotension during the procedure occurred in 22.9% (36), bleeding in 23.6% (37), perforation in 3.2% (5), and the in-hospital mortality was 19.7% (31) (Figure 1). The median procedure time was 84 (54, 129) minutes, and the median contrast volume was 158 (100, 225) mL.

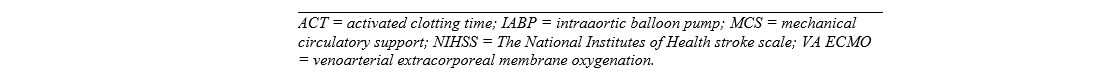

Table 5 presents a summary of key studies reporting periprocedural stroke outcomes in patients undergoing PCI. Stroke incidence ranged from 0.13% to 0.96%, with most studies reporting rates between 0.2% and 0.7%. In-hospital mortality among patients who experienced stroke varied from 12.5% to 37.2%. Long-term follow-up data were limited; however, when reported, they demonstrated high rates of mortality and MACE.

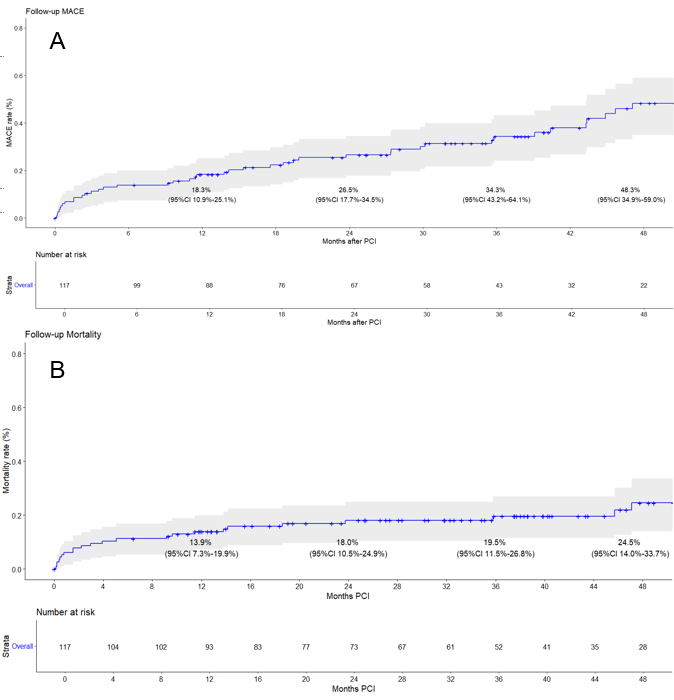

The median follow-up duration was 32 months. At the 1-, 2-, 3- and 4-year follow-up, the incidence of MACE was 18.3%, 26.5%, 34.3%, and 48.3%, respectively (Figure 2A). Mortality at the 1-, 2-, 3- and 4-year follow-up was 13.9%, 18.0%, 19.5%, and 24.5%, respectively (Figure 2B). The reported follow-up MACE and mortality rates were calculated as Kaplan-Meier cumulative estimates starting from the time of hospital discharge, thereby excluding patients who experienced in-hospital MACE or died during the index hospitalization. Therefore, the follow-up mortality rates represent post-discharge mortality. When both in-hospital and post-discharge deaths were considered together, the total 4-year mortality rate was 36.3% (57/157 patients).

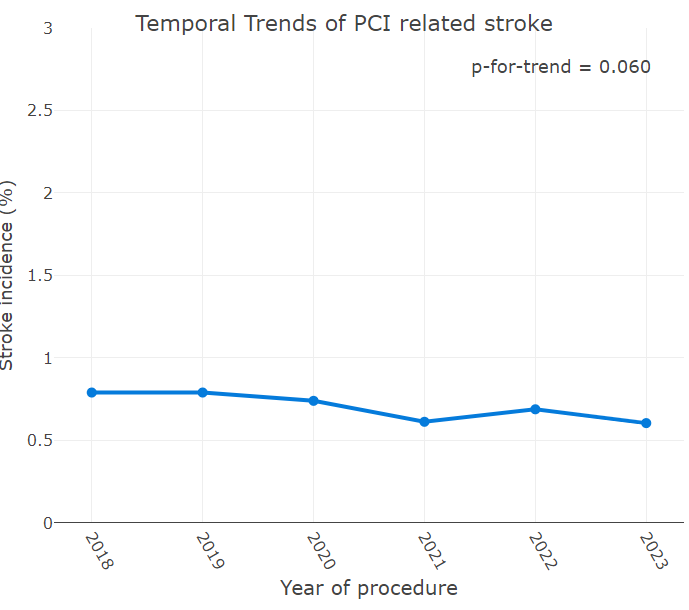

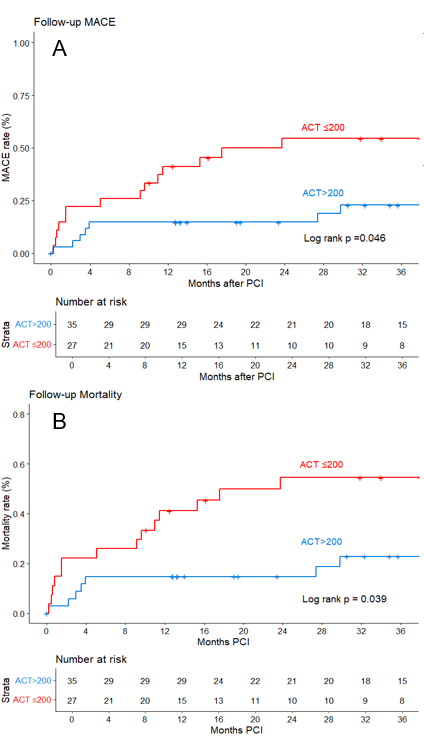

There was no significant change in the incidence of PCI-related stroke over time (Figure 3). In the Kaplan-Meier analysis, compared with patients with an ACT of greater than 200 seconds, patients with an ACT of less than or equal to 200 seconds had higher follow-up MACE and follow-up mortality (Figure 4A and Figure 4B, respectively).

Discussion

The major findings of our study are that PCI-related stroke: (a) occurred in 0.7% of patients without significant change in incidence over time; (b) was ischemic in most patients; (c) was associated with ACS presentation; and (d) was associated with high in-hospital and follow-up MACE and mortality.

The reported incidence of PCI-related stroke ranges from 0.18%1,2 to 1.2%.15-17 However, much of this data is derived from studies conducted more than a decade ago. Recent studies suggests an upward trend in stroke incidence over time, likely driven by higher patient complexity.18 Our study, encompassing a large and heterogeneous patient population across various age groups and clinical presentations, demonstrated a PCI-related stroke incidence of 0.18%. We did not observe a significant change in the incidence of stroke during the study period.

Most PCI-related strokes occur either during the procedure itself or within the first 24 hours following PCI and are due to thromboembolism.19 Hemorrhagic strokes account for approximately 10% to 40% of all PCI-related strokes.5,20 Because of significant differences in treatment, performing cerebral imaging (CT or MRI) before initiating stroke-specific treatment is critically important to distinguish between ischemic and hemorrhagic etiologies.19 In our study, the rate of hemorrhagic stroke was lower than previously reported (6.4%). There are some conditions that may mimic stroke, such as cortical blindness.21 Patients with cortical blindness typically demonstrate spontaneous resolution of symptoms and generally have a favorable neurological prognosis.21

Prior studies have identified several clinical factors independently associated with PCI-related stroke, including advanced age, diffuse vascular disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, a prior history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, heart failure, the use of MCS devices, and presentation with ACS.22-25 Our patients were older and had a high prevalence of comorbidities. The high MCS use suggests that these procedures were performed in higher risk settings and involved patient populations prone to hemodynamic instability during PCI. Alkhouli et al showed that most patients who developed PCI-related stroke had presented with ACS complicated by cardiac arrest or cardiogenic shock.22

Prior research has identified several technical and procedural characteristics associated with PCI-related stroke, including access site, target lesion characteristics, and the use of anticoagulation during the procedure.19,26,27 Similar to prior studies, we found high prevalence of complex coronary lesions, especially calcified lesions, among patients who developed PCI-related stroke.19 These findings suggest that both patient-specific and procedural factors contribute to stroke risk.

In our study, MCS devices were used in 20% of patients, with IABP being the most frequently utilized device, followed by the Impella CP (Abiomed, Inc.) and venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. In the Microaxial Flow Pump or Standard Care in Infarct-Related Cardiogenic Shock (DanGer-Shock) trial, routine implantation of the Impella CP device in patients with STEMI complicated by cardiogenic shock reduced 6-month mortality.28 The composite adverse event endpoint in the trial included moderate or severe bleeding, limb ischemia, stroke, the need for renal replacement therapy, and positive blood cultures indicating sepsis. Although routine Impella CP implantation was associated with higher incidence of adverse events, there was no significant difference in the incidence of stroke.28

Similar to our study, other investigators have reported high in-hospital and long-term MACE and mortality in patients with PCI-related stroke8,22: those risks have not declined, despite advancements in interventional techniques, pharmacotherapy, and supportive care.22 Lower ACT levels have been associated with a higher risk of ischemic procedural complications.12,29 However, in most of these studies, stroke was not analyzed as an isolated outcome, but as part of a composite ischemic adverse event endpoint, and long-term follow-up data were lacking.12 A key contribution of our study is that achieving optimal periprocedural anticoagulation with close ACT monitoring may be important for prevention and treatment of PCI-related stroke.

A definitive ACT threshold for preventing PCI-related stroke remains unestablished; however, current evidence indicates that maintaining therapeutic anticoagulation is effective in reducing periprocedural thrombotic complications.10 A meta-analysis conducted by Chew et al showed that ACT values ranging from 350 to 375 seconds could reduce the risk of ischemic events but carry an increased risk of bleeding.11 In the FUTURA/OASIS-8 trial, ACT levels of less than or equal to 300 seconds in NSTEMI patients correlated with a higher incidence of thrombotic events, while not significantly increasing the risk of bleeding.30 Additionally, elevated ACT values, especially during transfemoral PCI, are associated with increased rates of bleeding and mortality. The findings highlight the necessity of balancing sufficient anticoagulation with the risk of bleeding and support the careful targeting of therapeutic ACT levels during PCI procedures.31,32

Limitations

The present study was observational and retrospective with all inherent limitations. Additionally, the procedures were conducted at a single center with experienced PCI operators, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to less experienced centers. Another limitation is the lack of data on the control group who did not suffer stroke, which prevented us from comparing the two populations and identifying predictors of PCI-related stroke, including access site. Angiographic characteristics were not adjudicated by a core laboratory, and clinical events were not adjudicated by an independent clinical event committee.

Conclusions

Stroke is an infrequent but severe complication of PCI with high mortality and MACE. Most periprocedural strokes are ischemic.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Ozgur Selim Ser, MD1; Deniz Mutlu, MD1; Dimitrios Strepkos, MD1; Pedro E. Carvalho, MD1; Michaella Alexandrou, MD1; Eleni Kladou, MD1; Olga Mastrodemos, BA1; Silvia Moscardelli, MD2; Primero Ng, MD2; Bavana V. Rangan, BDS, MPH1; Jas D. Sara, MD1; Sandeep Jalli, MD1; Konstantinos Voudris, MD1; Lorenzo Azzalini, MD, PhD, MSc2; Yader Sandoval, MD1; M. Nicholas Burke, MD1; Emmanouil S. Brilakis, MD, PhD1

From the 1Minneapolis Heart Institute and Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, Abbott Northwestern Hospital, Minneapolis, Minnesota; 2Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

Acknowledgments: The authors are grateful for the philanthropic support of our generous anonymous donors (2), and the philanthropic support of Drs Mary Ann and Donald A.Sens; Mrs Diane and Dr Cline Hickok; Mrs Wilma and Mr Dale Johnson; the Mrs Charlotte and Mr Jerry Golinvaux Family Fund; the Roehl Family Foundation; the Joseph Durda Foundation; Ms Marilyn and Mr William Ryerse; and Mr Greg and Mrs Rhoda Olsen. The generous gifts of these donors to the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation’s Science Center for Coronary Artery Disease (CCAD) helped support this research project.

Disclosures: Dr Azzalini has received consulting fees from Teleflex, Abiomed, GE Healthcare, Abbott Vascular, Reflow Medical, Boston Scientific, HeartFlow, Shockwave, and Cardiovascular Systems, Inc.; and owns equity in Reflow Medical. Dr Sandoval is a consultant for, and on the advisory board of Abbott and GE Healthcare; is a consultant for, on the advisory board of, and a speaker for Roche Diagnostics and Philips; is on the advisory board of Zoll; is a consultant for CathWorks; is a speaker for HeartFlow; is a speaker for, and has received a research grant from Cleerly; is an associate editor for JACC Advances; and he and others hold patent 20210401347. Dr Burke has received consulting and received speaker honoraria from Abbott Vascular and Boston Scientific. Dr Brilaki receives consulting/speaker honoraria from Abbott Vascular, the American Heart Association (associate editor, Circulation), Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Cardiovascular Innovations Foundation (Board of Directors), Cordis, CSI, Elsevier, GE Healthcare, Haemonetics, IMDS, Medtronic, SIS Medical, Teleflex, and Orbus Neich; receives research support from Boston Scientific and GE Healthcare; is the owner of Hippocrates LLC; and is a shareholder in LifeLens Technologies, Inc., MHI Ventures, Cleerly Health, Stallion Medical, and TrueVue, Inc.

Address for correspondence: Emmanouil S. Brilakis, MD, PhD, Minneapolis Heart Institute, 920 E 28th Street #300, Minneapolis, MN 55407, USA. Email: esbrilakis@gmail.com; X: @esbrilakis

References

1. Wong SC, Minutello R, Hong MK. Neurological complications following percutaneous coronary interventions (a report from the 2000-2001 New York State Angioplasty Registry). Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(9):1248-1250. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.065

2. Abtan J, Wiviott SD, Sorbets E, et al; TAO investigators. Prevalence, clinical determinants and prognostic implications of coronary procedural complications of percutaneous coronary intervention in non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: insights from the contemporary multinational TAO trial. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;114(3):187-196. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2020.09.005

3. Murakami T, Sakakura K, Jinnouchi H, et al. Acute ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention. J Clin Med. 2023;12(3):840. doi:10.3390/jcm12030840

4. Werner N, Bauer T, Hochadel M, et al. Incidence and clinical impact of stroke complicating percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the Euro heart survey percutaneous coronary interventions registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6(4):362-369. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.000170

5. Fuchs S, Stabile E, Kinnaird TD, et al. Stroke complicating percutaneous coronary interventions: incidence, predictors, and prognostic implications. Circulation. 2002;106(1):86-91. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000020678.16325.e0

6. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al; REDCap Consortium. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

7. Mendelson SJ, Prabhakaran S. Diagnosis and management of transient ischemic attack and acute ischemic stroke: a review. JAMA. 2021;325(11):1088-1098. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.26867

8. Wexler NZ, Vogrin S, Brennan AL, al. Adverse impact of peri-procedural stroke in patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2022;181:18-24. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2022.06.063

9. Lunardi M, Louvard Y, Lefèvre T, et al. Definitions and standardized endpoints for treatment of coronary bifurcations. EuroIntervention. 2023;19(10):e807-e831. doi:10.4244/EIJ-E-22-00018

10. Ndrepepa G, Kastrati A. Activated clotting time during percutaneous coronary intervention: a test for all seasons or a mind tranquilizer? Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(4):e002576. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.002576

11. Chew DP, Bhatt DL, Lincoff AM, et al. Defining the optimal activated clotting time during percutaneous coronary intervention: aggregate results from 6 randomized, controlled trials. Circulation. 2001;103(7):961-966. doi:10.1161/01.cir.103.7.961

12. Simsek B, Rempakos A, Kostantinis S, et al. Activated clotting time and outcomes of chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the PROGRESS-CTO Registry. J Invasive Cardiol. 2023;35(12). doi:10.25270/jic/23.00170

13. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al; Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Circulation. 2018;138(20):e618-e651. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000617

14. Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123(23):2736-2747. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449

15. Korn-Lubetzki I, Farkash R, Pachino RM, Almagor Y, Tzivoni D, Meerkin D. Incidence and risk factors of cerebrovascular events following cardiac catheterization. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(6):e000413. doi:10.1161/JAHA.113.000413

16. Vranckx P, Frigoli E, Rothenbühler M, et al; MATRIX Investigators. Radial versus femoral access in patients with acute coronary syndromes with or without ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(14):1069-1080. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx048

17. Elgendy IY, Mahmoud AN, Kumbhani DJ, Bhatt DL, Bavry AA. Complete or culprit-only revascularization for patients with multivessel coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(4):315-324. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2016.11.047

18. Nelson AJ, Young R, Tarrar IH, Wojdyla D, Wang TY, Mehta RH. Temporal trends in risk factors of periprocedural stroke in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the ACC NCDR CathPCI registry. Am J Cardiol. 2023;204:284-286. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2023.07.104

19. Werner N, Zahn R, Zeymer U. Stroke in patients undergoing coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention: incidence, predictors, outcome and therapeutic options. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;10(10):1297-1305. doi:10.1586/erc.12.78

20. Dukkipati S, O'Neill WW, Harjai KJ, al. Characteristics of cerebrovascular accidents after percutaneous coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(7):1161-1167. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.033

21. Vranckx P, Ysewijn T, Wilms G, Heidbüchel H, Herregods MC, Desmet W. Acute posterior cerebral circulation syndrome accompanied by serious cardiac rhythm disturbances: a rare but reversible complication following bypass graft angiography. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 1999;48(4):397-401. doi:10.1002/(sici)1522-726x(199912)48:4<397::aid-ccd16>3.0.co;2-c

22. Alkhouli M, Alqahtani F, Tarabishy A, Sandhu G, Rihal CS. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of acute ischemic stroke following percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12(15):1497-1506. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2019.04.015

23. Khera R, Cram P, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Horwitz PA, Girotra S. Use of mechanical circulatory support in percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117(1):10-16. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.10.005

24. Yamamoto K, Natsuaki M, Morimoto T, et al; CREDO-Kyoto PCI/CABG Registry Cohort-3 investigators. Periprocedural stroke after coronary revascularization (from the CREDO-Kyoto PCI/CABG Registry Cohort-3). Am J Cardiol. 2021;142:35-43. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.11.031

25. Song C, Sukul D, Seth M, et al. Outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with a history of cerebrovascular disease: insights from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(6):e006400. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.006400

26. Valle JA, Kaltenbach LA, Bradley SM, et al. Variation in the adoption of transradial access for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: insights from the NCDR CathPCI registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(22):2242-2254. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2017.07.020

27. Gui YY, Huang FY, Huang BT, et al. The effect of activated clotting time values for patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2016;144:202-209. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2016.04.025

28. Møller JE, Engstrøm T, Jensen LO, et al; DanGer Shock Investigators. Microaxial flow pump or standard care in infarct-related cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(15):1382-1393. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2312572

29. Rajpurohit N, Gulati R, Lennon RJ, et al. Relation of activated clotting times during percutaneous coronary intervention to outcomes. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117(5):703-708. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.12.003

30. Ducrocq G, Jolly S, Mehta SR, et al. Activated clotting time and outcomes during percutaneous coronary intervention for non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: insights from the FUTURA/OASIS-8 trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(4):e002044. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.002044

31. Louis DW, Kennedy K, Lima FV, et al. Association between maximal activated clotting time and major bleeding complications during transradial and transfemoral percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(11):1036-1045. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2018.01.257

32. Kwok CS, Kontopantelis E, Myint PK, et al; British Cardiovascular Intervention Society; National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research. Stroke following percutaneous coronary intervention: type-specific incidence, outcomes and determinants seen by the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society 2007-12. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(25):1618-1628. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv113