Balloon-Assisted Paravalvular Leakage Crossing for Transcatheter Closure: A Pilot Study

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Objectives. Transcatheter closure of paravalvular leaks (PVL) is an established treatment method. However, because of the frequent anatomical complexity of the PVL channel and lack of dedicated equipment, PVL crossing remains challenging. This study aims to provide an initial assessment of the safety and efficacy of using an angioplasty balloon to facilitate PVL passage.

Methods. The authors describe 12 cases of predilatation of the PVL tract using a coronary balloon after an attempt to pass the sheath was unsuccessful.

Results. In each case, the procedure was successful with final implantation of the occluder. No adverse events directly related to the technique were observed.

Conclusions. The technique of traversing the PVL channel using small coronary balloons may be an effective alternative method. Results of this registry are a preview of further research into the development and improvement of the described technique.

Introduction

The transcatheter closure of paravalvular leaks (PVL) around surgically implanted heart valves is an established treatment method. The European Society of Cardiology and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines categorize this treatment method as Class IIa for specific patient groups.1-3 One limitation of transcatheter PVL closure is the technically complicated nature of the procedure; this pertains to both obtaining proper access to the PVL channel and navigating the delivery sheath, as well as the implantation of the occluders.

The challenge of passing through the leak channel with the delivery sheath often arises from the highly irregular shape of the channel itself, which frequently includes protruding calcifications into its lumen. One approach to facilitate passage through the PVL may be pre-dilation of the channel using an angioplasty balloon. This study aims to provide an initial assessment of the safety and efficacy of such a strategy.

Methods

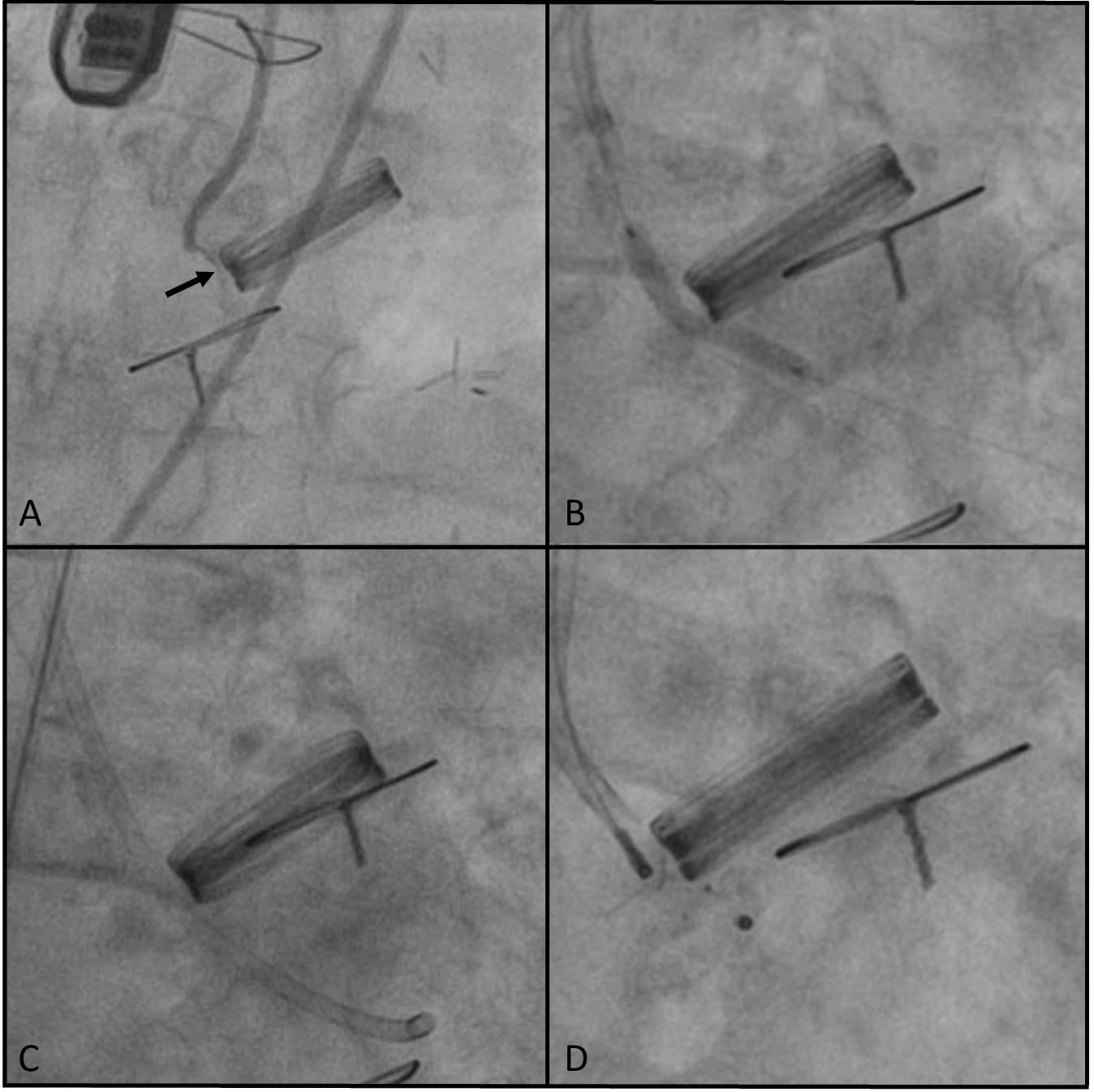

The study is a registry of all transcatheter PVL closure procedures performed in 3 high-volume centers in which predilation of the channel lumen was performed using a noncompliant coronary angioplasty balloon after a failed attempt to navigate the delivery sheath through the PVL channel. The size of the balloon was estimated to correspond to the outer diameter of the intended delivery sheath, which was the sheath with the smallest diameter allowing for the planned occluder implantation. The technique for using the angioplasty balloon involved positioning it within the PVL channel such that the distal part of the balloon remained within the delivery sheath, while the remainder of the balloon was used to dilate (smoothen) the lumen of the PVL channel. After achieving balloon expansion, the sheath was advanced over the deflating balloon through the PVL channel (Figure). All subjects gave their informed consent for the interventions described in the manuscript, and the study was conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines.

All procedures were performed under fluoroscopic guidance and simultaneous real-time 3-dimensional (3D) transesophageal echocardiography. Standard procedural data were recorded, along with additional efficacy and safety parameters of the applied technique. Potential complications of this technique may include local (such as damage to perivalvular structures and its consequences, or balloon entrapment) as well as systemic complications related to the release of embolic material from the PVL channel. These events were monitored in all cases, with the endpoint for embolic complications being the occurrence of clinically evident embolism. The efficacy parameters included successful passage of the delivery sheath after predilation and successful implantation of the occluder (defined as technical success).

Results

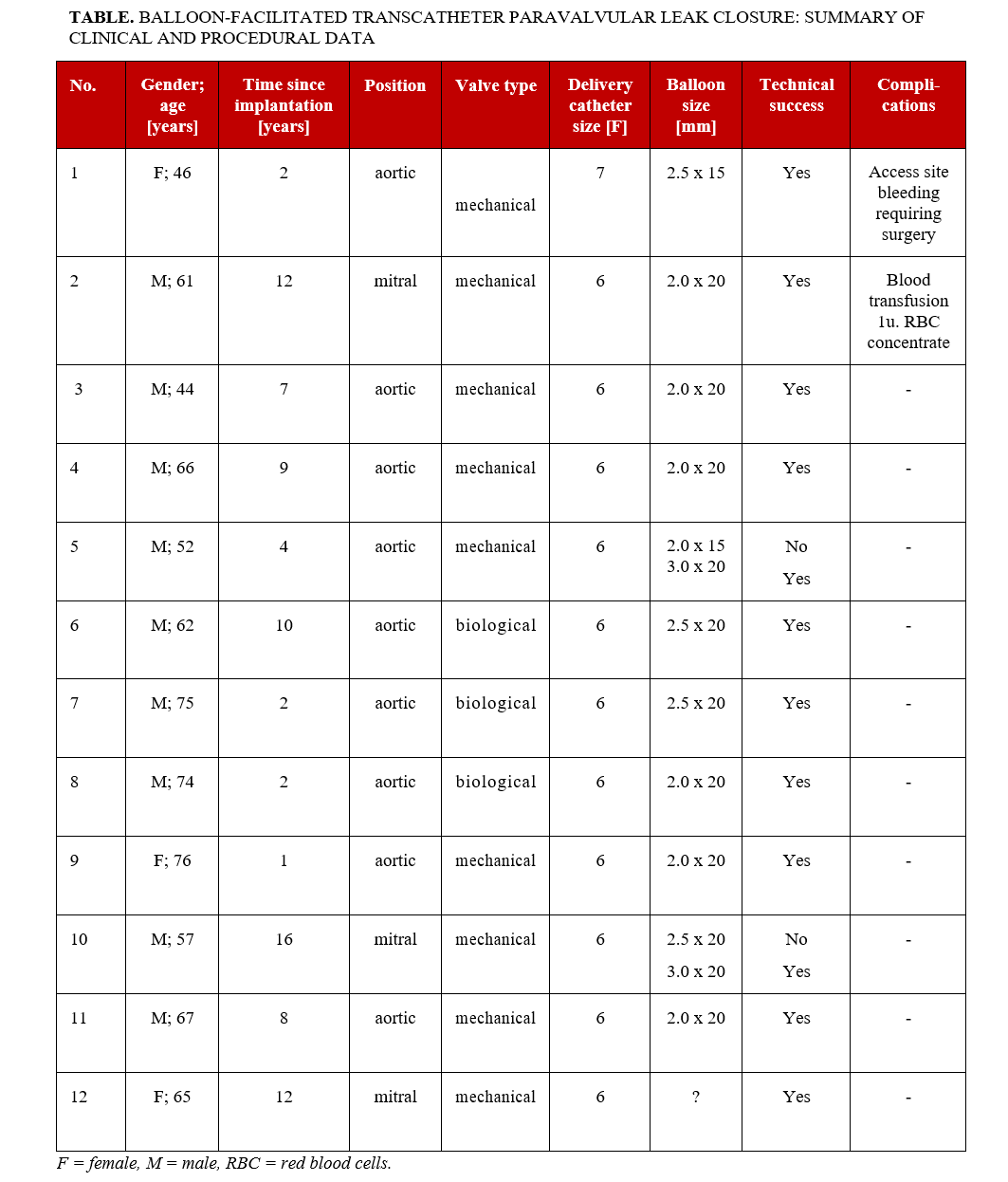

The study included 12 patients aged 46 to 76 years (median 66.5 years); 9 (75%) patients were male. The median time since surgical valve implantation to transcatheter PVL closure was 7.5 years. Aortic localization and mechanical valves were predominant. A detailed summary of clinical and procedural data is provided in the Table.

In most cases, the occluders were implanted using a 6F coronary guiding catheter for delivery, and a 2.0-mm balloon was utilized to facilitate passage through the PVL channel. The difficulties encountered with the delivery catheter were due to the small size and unfavorable shape of the PVL channel (slit-like), which often also had a tortuous course along its long axis. The balloon catheters were inflated under fluoroscopic guidance until full expansion with no waist was achieved. This did not require the application of pressures exceeding those that are standard for regular angioplasty balloons, nor were high-pressure balloons used. In 1 instance, the operator opted to use a balloon with a diameter that exceeded that of the delivery sheath, specifically a 3.0-mm balloon for a 6F sheath. The use of this balloon was preceded by an attempt to navigate through the PVL channel with a 2.0-mm balloon, which proved to be ineffective. In each case, the occluder was implanted in the size that was originally planned. There was no need to increase the size of the occluder after balloon predilatation. No periprocedural complications or clinical signs of central/peripheral embolism were observed during the procedure. During the post-procedural hospitalization, 2 patients experienced complications unrelated to the assessed technique.

Discussion

Transcatheter PVL closure is a significantly less invasive method than reoperation. However, the main limitation of this approach is its technical complexity. In the literature, the effectiveness of transcatheter procedures ranges from 85.0% to 91.4% for mitral and aortic procedures, respectively.4

Some procedural approaches exist regarding valve type, its position, and PVL location; however, in the majority of cases, anterograde transseptal mitral valve and retrograde aortic techniques are used. Because of the oblique axis of the leak, serpiginous track, and calcifications, crossing the defect with the wire and delivery sheath can be challenging. High-quality echocardiography assessment using 2D, 3D, and multiplanar reconstruction is of great importance to guide PVL channel crossing.

Several techniques facilitating PVL crossing have already been described. Generally, most of these techniques involve either enhancing the support for the delivery sheath or improving its axial alignment relative to the PVL channel. A classical technique in this context is to snare the guidewire, thereby providing additional support for the delivery sheath.5 A limitation of this method is the presence of a mechanical valve in the path of the guidewire, although procedures have also been described in which the guidewire was passed through the lumen of a mechanical valve.6,7

An important step forward is the use of large (12F-14F) steerable sheaths for transseptal paramitral leak closure. Positioned above the entrance to the PVL channel, these steerable sheaths serve as a port, improving coaxiality and increasing support for the delivery sheath(s).8 Attempts are also being made to modify the PVL channel in ways other than standard predilatation. These include lithotripsy, which was used to facilitate passage through the PVL channel alongside the transcatheter aortic valve implantation valve.9

In this pilot study, we described 12 transcatheter PVL closure procedures in which predilation of the channel lumen was performed using an angioplasty balloon after a failed attempt to navigate the delivery sheath through the PVL channel. Predilatation with a small coronary balloon facilitated the PVL crossing in all cases. The mechanism of facilitating the passage of the delivery catheter through balloon predilatation does not necessarily always result from a permanent enlargement of the PVL channel. In many cases, recoil of the lumen was observed after predilatation, and only simultaneous introduction of the delivery catheter while deflating the balloon (using the balloon to create the pathway for the catheter) proved effective.

Despite the small number of described procedures, there is a clear dominance of paraaortic procedures in the studied group. This may be due to the often-tortuous course of the channel in this location (as the valve is often implanted in a supraannular position, which affects the shape of any potential PVL) and the usually significant calcifications of the aortic root.

Limitations

This pilot study has some significant limitations. The first of these is the relatively small size of the study group. It should be noted, however, that this technique is generally rarely used, and its utility may be limited to slit-like PVLs, which are usually closed because of hemolysis. In our study, the technique described was utilized in approximately 3% of all patients undergoing transcatheter PVL closure. The conclusions from this registry should also not be generalized to situations where larger balloons than those described are used to facilitate passage through the PVL channel. It should also be taken into account that all procedures described in this registry were performed a considerable time after the valve implantation. The safety of balloon predilation shortly after valve implantation cannot be determined based on this registry.

Conclusions

The technique of traversing the PVL channel using small coronary balloons may be an effective alternative to other methods. However, this requires validation through a larger number of observations. Therefore, the results of this registry should be regarded as generating a research hypothesis for further studies.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Aleksander Olejnik, MD¹; Monika Słaba, MD¹; Michał Majewski, MD, PhD²; Ainars Rudzitis, MD, PhD³; Benoit Gerardin, MD, PhD⁴; Wojciech Wojakowski, MD, PhD5; Grzegorz Smolka, MD, PhD²

From the ¹Department of Cardiology, Upper Silesia Medical Centre, Katowice, Poland; ²Department of Cardiology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland; ³Latvian Centre of Cardiology, Pauls Stradins Clinical University Hospital, Riga, Latvia; ⁴Marie Lannelongue Hospital, Groupe Hospitalier Paris Saint Joseph, Faculté De Médecine Paris-Saclay, Université Paris-Saclay, Le Plessis Robinson, France; 5Division of Cardiology and Structural Heart Diseases, Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland.

Disclosures: The authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Address for correspondence: Aleksander Olejnik, MD, Department of Cardiology, Upper Silesia Medical Centre, Ziołowa 45/47, 40-635 Katowice, Poland. Email: aolejnik@gcm.pl

References

- Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2021;43(7):561-632. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395

- Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(4):e25-e197. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.018

- Ruiz CE, Hahn RT, Berrebi A, et al; Paravalvular Leak Academic Research Consortium. Clinical trial principles and endpoint definitions for paravalvular leaks in surgical prosthesis: an expert statement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(16):2067-2087. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.02.038

- Hascoët S, Smolka G, Blanchard D, et al. Predictors of clinical success after transcatheter paravalvular leak closure: an international prospective multicenter registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15(10):e012193. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.122.012193

- García E, Sandoval J, Unzue L, Hernandez-Antolin R, Almería C, Macaya C. Paravalvular leaks: mechanisms, diagnosis and management. EuroIntervention. 2012;8 Suppl Q:Q41-Q52. doi:10.4244/EIJV8SQA9

- Hascoët S, Smolka G, Kilic T, et al; EuroPVLc Study Group. Procedural tools and technics for transcatheter paravalvular leak closure: lessons from a decade of experience. J Clin Med. 2022;12(1):119. doi:10.3390/jcm12010119

- Cruz-Gonzalez I, Rama-Merchan JC, Martín-Moreiras J, Rodríguez-Collado J, Arribas-Jimenez A. Percutaneous retrograde closure of mitral paravalvular leak in patients with mechanical aortic valve prostheses. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29(11):1531.e15-e16. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2013.07.004

- Kozłowski M, Pysz P, Wojakowski W, Smolka G. Improved transseptal access for transcatheter paravalvular leak closure using steerable delivery sheaths: data from a prospective registry. J Invasive Cardiol. 2019;31(8):223-228.

- Evola S, D’Agostino A, Adorno D, et al. Intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) enabled the percutaneous closure of a severely calcified paravalvular leak regurgitation following implantation of a self-expandable transcatheter aortic valve: a case report. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1359711. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2024.1359711