Pocket Erosion in a Patient With Bullous Pemphigoid: A Dual Dermatologic and Device-Related Challenge

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

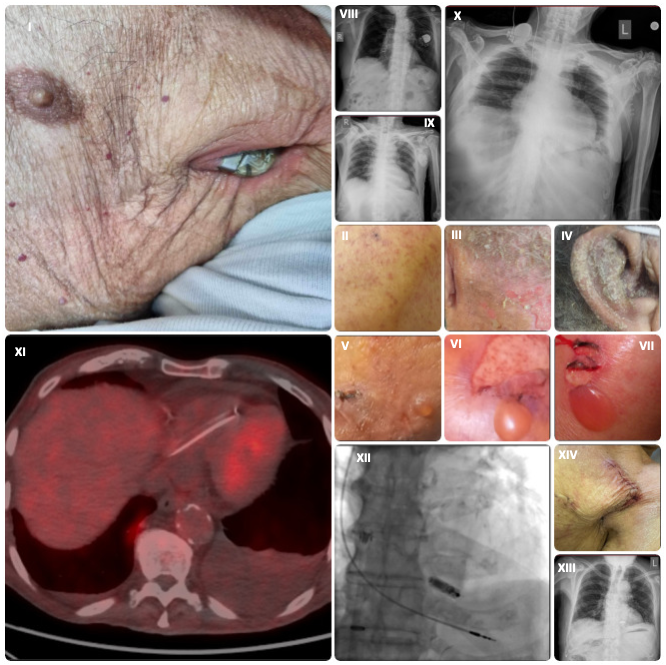

An 89-year-old man with a dual-chamber pacemaker implanted 4 years ago presented with pocket erosion and pacemaker exterorization through the left anterior chest wall (Figure I). He had a known diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid, histologically confirmed 2 years prior. In the weeks leading up to presentation, he experienced a prodromal flare characterized by intense pruritus and widespread eczematous plaques, predominantly involving the occipital scalp, nuchal region, and external auricles (notably the conchal bowl and external auditory meatus) (Figure II-IV); this seborrheic-pattern eczema is frequently seen in prodromal bullous pemphigoid.

Upon examination, tense bullae were evident on the groin, inner thighs, and extremities, and the Nikolsky sign was negative (Figure V-VII); these findings are characteristic of the bullous phase of the disease.1 Chest radiographs demonstrated the original post-implantation generator position and its subsequent superficial migration and exteriorization through the thoracic wall (Panels VIII, IX). The generator had eroded through the device pocket and overlying atrophic skin; however, device interrogation confirmed its preserved function. Transthoracic echocardiography showed no evidence of valvular vegetations or lead-associated thrombus.

The pacemaker and leads were explanted and pocket debridement was perfomed. Temporary pacing via a transjugular permanent active-fixation lead secured an adequate heart rate (Figure X). Despite 3 sets of blood cultures obtained prior to the device explantation being negative, an 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG PET-CT) scan was performed because of a low-grade fever to assess for occult infection. No abnormal cardiac or systemic uptake was demonstrated, effectively ruling out device-related endocarditis (Panel XI). Empiric intravenous vancomycin (15 mg/kg q12h) was administered perioperatively and discontinued after 10 days following confirmation of microbiological clearance with negative cultures from the extracted leads as well.2 A leadless Micra transcatheter pacemaker (Medtronic) was successfully implanted via femoral access and the temporary system was then removed (Panel XII).3 Post-procedure imaging confirmed appropriate device placement (Panel XIII), and post-explantation wound healing was uncomplicated and satisfactory (Panel XIV).

This case highlights the potential role of autoimmune blistering disease as a contributing factor in pacemaker pocket erosion and supports leadless pacing as an alternative approach in older patients with compromised skin. FDG PET-CT proved a valuable tool in excluding occult infection and guiding safe reimplantation.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Dimitrios Karelas, MD1; Konstantinos Giannopoulos, MD2; Ioannis Tsiafoutis, MD, PhD1; Savvas Nikolidakis, MD1

From the 12nd Cardiology Department, Red Cross “Korgaleneio-Benakeio” General Hospital, Athens, Greece; 2Department of Dermatology, Red Cross “Korgaleneio-Benakeio” General Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Disclosures: The authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Consent statement: The authors confirm that informed consent was obtained from the patient for the intervention(s) described in the manuscript and for the publication thereof, including any and all images.

Address for correspondence: Dimitrios Karelas, MD, Athanasaki 2, Athens 11526, Greece. Email: dim.f.karelas@gmail.com

References

1. Akbarialiabad H, Schmidt E, Patsatsi A, et al. Bullous pemphigoid. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2025;11(1):12. doi:10.1038/s41572-025-00595-5

2. Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(39):3948-4042. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehad193

3. Baddour LM, Esquer Garrigos Z, Rizwan Sohail M, et al; American Heart Association Council on Lifelong Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young (Young Hearts); Council on Clinical Cardiology. Update on cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections and their prevention, diagnosis, and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association: endorsed by the International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases. Circulation. 2024;149(2):e201-e216. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001187