Coronary Artery Ectasia With Optical Coherence Tomography-Confirmed Acute Coronary Syndrome With Intact Fibrous Cap

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

J INVASIVE CARDIOL 2025. doi:10.25270/jic/25.00322. Epub November 4, 2025.

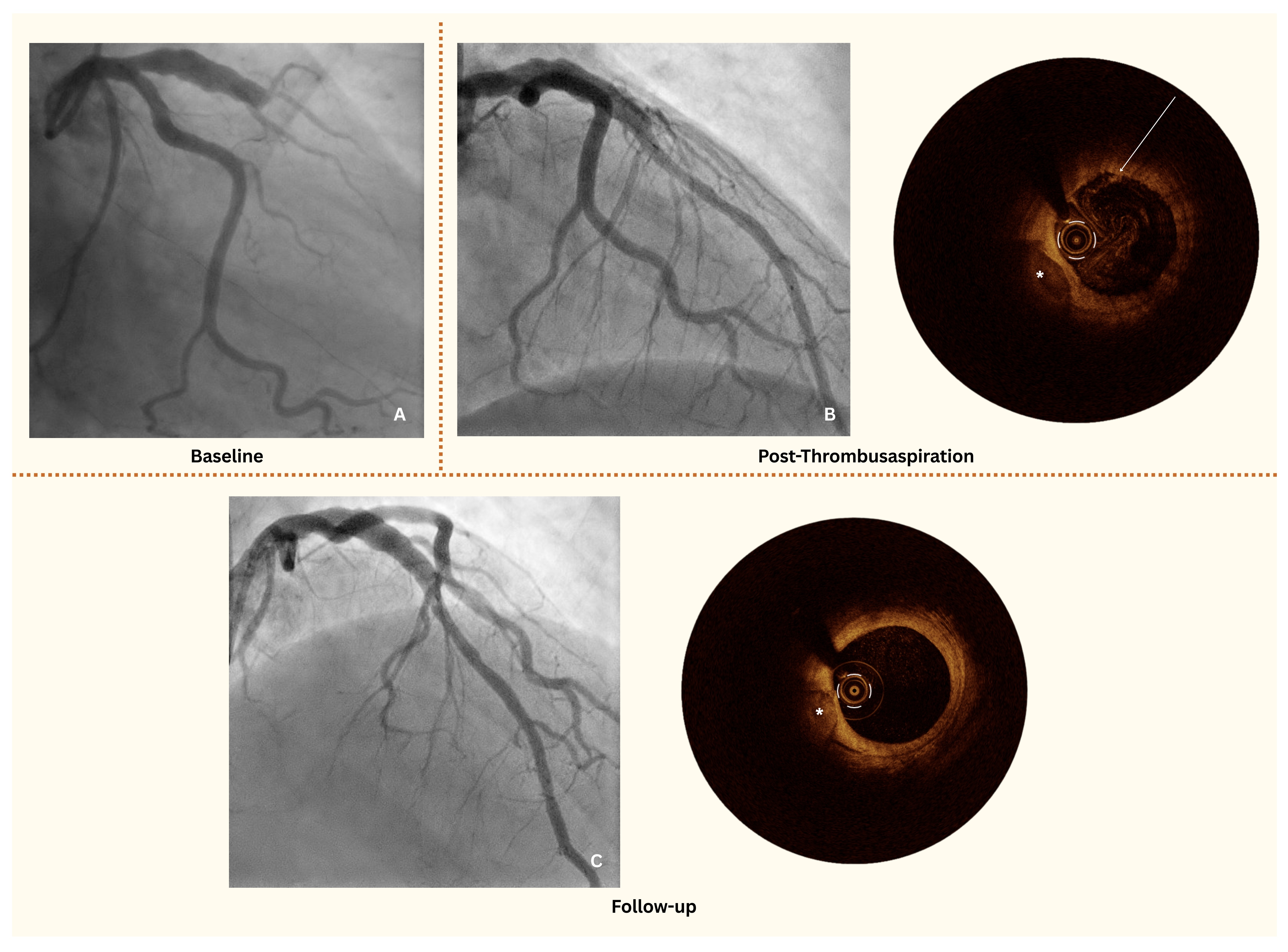

A 49-year-old man was transferred to our department by emergency medical services with an anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The patient reported left-sided thoracic pain radiating to the left arm, accompanied by autonomic symptoms with an onset approximately 8 hours prior to admission. The initial electrocardiogram (ECG) showed 2- to 3-mm ST-segment elevations in leads V3-V5. Coronary angiography revealed total thrombotic occlusion of the mid-left anterior descending artery (LAD), with notable adjacent coronary artery ectasia (CAE) (Figure A).

To further assess the culprit site, optical coherence tomography (OCT) was performed. While full circumferential imaging of the culprit site was achieved, assessment at the ectatic segment was limited because of the vessel's dilated morphology. OCT revealed a white thrombus overlying an intact fibrous cap, consistent with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) with intact fibrous cap (IFC), ie, coronary plaque erosion (Figure B, Video 1). However, there was no evidence of a significant coronary stenosis or plaque rupture, leading to the decision against stent implantation.

The patient was treated with thrombus aspiration followed by intracoronary tirofiban with a 24-hour infusion and dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with a planned duration of 12 months, and extended DAPT to be evaluated at follow-up. A follow-up coronary angiography with OCT at 6 weeks confirmed thrombus resolution and the absence of significant stenosis or pathological plaques in the LAD (Figure C, Video 2), supporting the effectiveness of the conservative approach.

CAE is observed in up to 5% of patients undergoing coronary angiography1 and, in the context of ACS, represents a clinical challenge: a 3- to 5-fold higher risk of subsequent adverse clinical events has been reported in some recent studies, and it has a unique pathophysiology.2 CAE is defined as a coronary segment dilated to at least 1.5 times the adjacent normal vessel and is associated with increased thrombus burden, impaired coronary flow, and a higher incidence of no-reflow phenomenon following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).3 The latter significantly contributes to adverse outcomes, including a potential risk of recurrent myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality.4,5

Given these risks, conventional management often includes aggressive mechanical intervention, such as aspiration thrombectomy and stent implantation, alongside intensified antithrombotic therapy.6 However, in our case, the decision was made against stent implantation and a conservative strategy was pursued.7 The rationale for this approach was guided by the absence of high-grade stenosis, calcified nodule, thin-cap fibroatheroma (TCFA), or plaque rupture on OCT,8 as well as by the identification of IFC-ACS (due to plaque erosion) as the underlying pathophysiology. This observation aligns with prior retrospective OCT studies in CAE, which reported signs of erosion in 65% to 70% of individuals.9

Stent implantation in ectatic coronary arteries can be challenging with respect to optimal stent apposition, an increased risk of in-stent restenosis or thrombosis, and potential late stent malapposition.6 Furthermore, CAE is associated with impaired endothelial function and altered hemodynamics, which may contribute to a prothrombotic state despite stenting.2

In this setting, an intravascular imaging modality such as OCT is especially valuable because it enables detailed plaque characterization and may aid in guiding treatment decisions in complex coronary anatomies.10 However, its utility may be limited in large or ectatic vessels because of reduced penetration depth and diminished image clarity at greater distances from the catheter, as well as the difficulty of achieving a complete 360° image.

Our case highlights that, in select patients with ACS and CAE, a conservative, antithrombotic-focused approach can be a viable alternative to stenting, particularly when intracoronary imaging does not indicate significant plaque instability or severe coronary artery stenosis. Follow-up OCT confirmed the resolution of thrombus and absence of significant stenosis, yielding satisfying short-term results and supporting the safety and efficacy of this approach. Further studies are needed to establish standardized management strategies for ACS in the setting of CAE, as current guidelines remain limited in addressing this subset of patients, including the potential need of a prolonged intense antithrombotic treatment strategy.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Elaaha Anwari, MD; Denitsa Meteva, MD; Ulf Landmesser, MD; Youssef S. Abdelwahed, MD

From the Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine, German Heart Center of the Charité, Berlin, Germany

Disclosures: Dr Abdelwahed has received consulting fees from Boston Scientific and Shockwave. Prof Dr Landmesser reports research support to institution from Abbott, Amgen, Bayer and Novartis. The remaining authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Consent statement: Patient consent was waived as the case details were anonymized and no identifiable information is included, in accordance with institutional and journal policies.

Address for correspondence: Elaaha Anwari, MD, Department of Cardiology, Angiology and Intensive Care Medicine, German Heart Center of the Charité, Hindenburgdamm 30, Berlin 12203, Germany. Email: elaaha.anwari@dhzc-charite.de; X: @elaaha_a

References

- Swaye PS, Fisher LD, Litwin P, et al. Aneurysmal coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1983;67(1):134-138. doi:10.1161/01.cir.67.1.134

- Doi T, Kataoka Y, Noguchi T, et al. Coronary artery ectasia predicts future cardiac events in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(12):2350-2355. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309683

- Schram HCF, Hemradj VV, Hermanides RS, Kedhi E, Ottervanger JP; Zwolle Myocardial Infarction Study Group. Coronary artery ectasia, an independent predictor of no-reflow after primary PCI for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2018;265:12-17. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.04.120

- Wang X, Montero-Cabezas JM, Mandurino-Mirizzi A, et al. Prevalence and long-term outcomes of patients with coronary artery ectasia presenting with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2021;156:9-15. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.06.037

- Baldi C, Silverio A, Esposito L, et al. Clinical outcome of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction and angiographic evidence of coronary artery ectasia. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;99(2):340-347. doi:10.1002/ccd.29738

- Esposito L, Di Maio M, Silverio A, et al. Treatment and outcome of patients with coronary artery ectasia: current evidence and novel opportunities for an old dilemma. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;8:805727. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.805727

- Jia H, Dai J, Hou J, et al. Effective anti-thrombotic therapy without stenting: intravascular optical coherence tomography-based management in plaque erosion (the EROSION study). Eur Heart J. 2017;38(11):792-800. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw381

- Abdelwahed YS, Nelles G, Frick C, et al. Coexistence of calcified- and lipid-containing plaque components and their association with incidental rupture points in acute coronary syndrome-causing culprit lesions: results from the prospective OPTICO-ACS study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;23(12):1598-605. doi:10.1093/ehjci/jeab247

- Yu H, Dai J, Tang H, et al. Characteristics of coronary artery ectasia and accompanying plaques: an optical coherence tomography study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023;39(7):1357-1366. doi:10.1007/s10554-023-02835-9

- Ali ZA, Karimi Galougahi K, Mintz GS, Maehara A, Shlofmitz RA, Mattesini A. Intracoronary optical coherence tomography: state of the art and future directions. EuroIntervention. 2021;17(2):e105-e123. doi:10.4244/EIJ-D-21-00089