Enhancing Productivity: How AI Chatbots Can Benefit Cardiologists

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

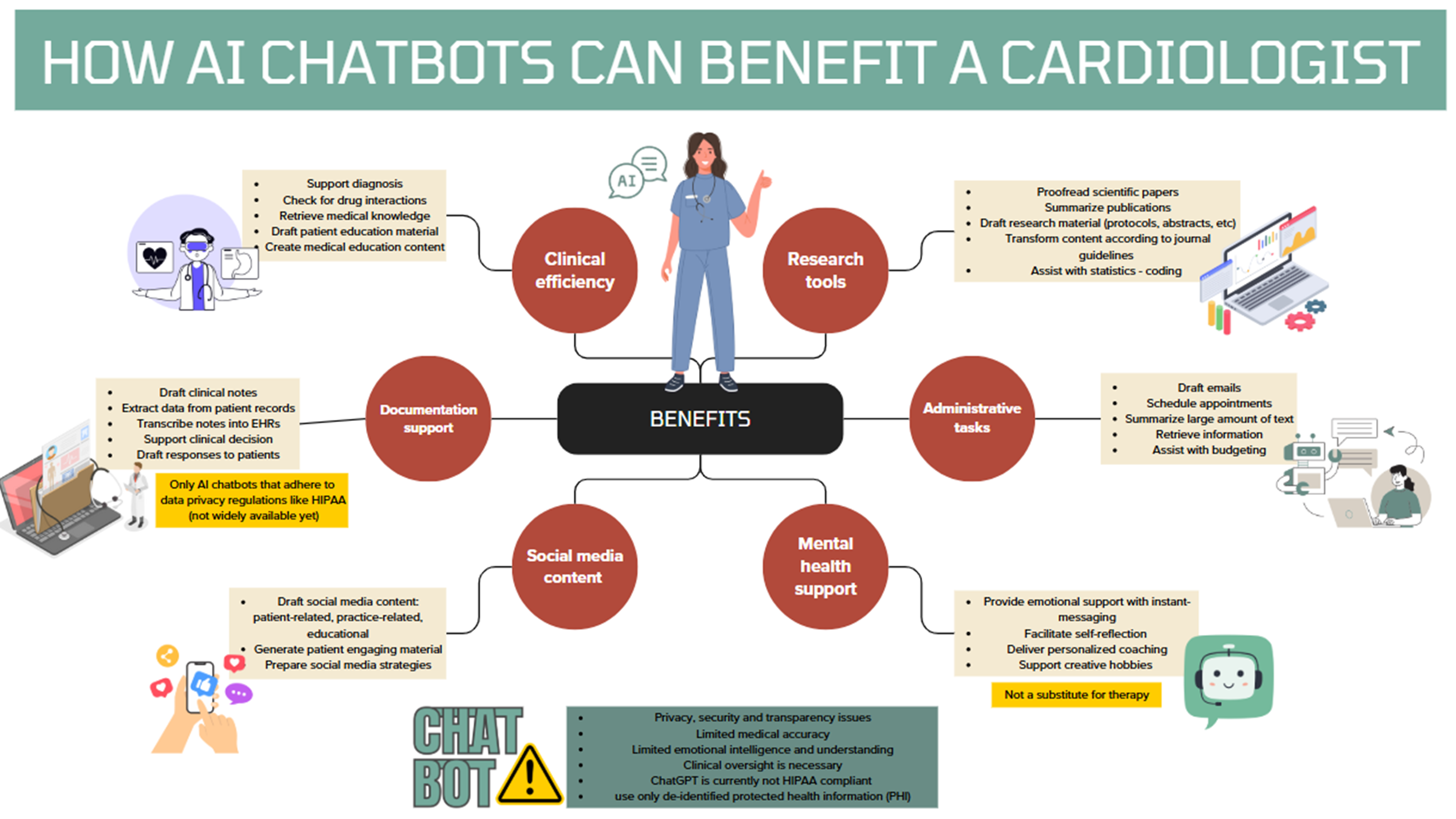

Artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots have become indispensable, engaging millions of users daily. ChatGPT (OpenAI) alone processes over 10 million queries per day, with usage quickly increasing as its quality improves and new models are launched. With the integration of AI into many facets of medicine, it is timely to explore how cardiologists could use AI chatbots in their daily clinical practice to enhance productivity (Figure).

AI chatbots can be useful in assisting with diagnosis and clinical decision making by retrieving relevant medical knowledge.1 Besides ChatGPT, there are other AI chatbots that are specifically trained on medical knowledge, like Med-PaLM 2 (Google Research), Med-Gemini (Google Research), and Meditron (Meta). ChatGPT passed multiple cardiology certification exams, including the Interventional Cardiology Certification Exam and the European Exam in Core Cardiology.2 However, further research is needed to evaluate their accuracy, reproducibility and transparency, as misleading responses may have high clinical significance, even when they are limited. Given the potential for hallucinations and limited evidence on their accuracy, the safest approach to using an AI chatbot for medical knowledge retrieval is to treat it as a knowledge assistant, cross-checking information with trusted sources and verifying any references provided.

AI chatbots can help cardiologists develop patient education material that simplifies complex medical concepts. A recent study demonstrated that ChatGPT-4-based translation substantially improved patient comprehension of discharge summary notes, with greater improvements among patients with low health literacy.3 Another study evaluated the performance of ChatGPT when asked common questions by patients regarding cardiac catheterization and it showed that it provided primarily reliable answers, with explanation still needed for most.1

AI chatbots may ease cardiologists’ documentation burden. Electronic health records (EHR) are a major contributor to cardiologists’ burnout, with documentation demands often extending their workload beyond regular hours. Integrating AI chatbots in EHR can help with drafting clinical notes, extracting data from patient records, transcribing patient encounters, and answering patients’ questions in real-time. In a recent study, ChatGPT 3.5 outperformed physicians in quality and empathy when answering patients' questions.4 While it is premature to declare AI chatbots as the solution to the problem of clinical documentation, integration of AI chatbots into EHR systems is likely imminent.

AI chatbots can facilitate cardiology research. Academic writing has benefited the most, allowing researchers to streamline otherwise time-consuming tasks. There is a variety of AI chatbots that are customized research tools like Consensus (Consensus), OpenEvidence (OpenEvidence), SciSpace (SciSpace) and Elicit (Ought). These tools provide AI-driven search engines for peer-reviewed material that can automate literature reviews, “chat” with a research paper, paraphrase, generate citations, extract data from papers, and proofread for grammar and spelling errors. A cross-sectional survey of corresponding authors of recent publications found that around half of respondents used an AI chatbot for purposes relating to the scientific process.5 AI chatbots can also help researchers handle statistics, write, and debug code, allowing for automated data analysis and assistance regarding complex statistical modeling.

AI chatbots could assist cardiologists with time management. Cardiologists are used to long working hours with limited time for themselves and their families. AI chatbots can reduce their workload by acting as virtual assistants: they can generate schedules, draft emails, summarize meetings, and create reports, all at a fraction of the time required for an average human. Beyond administrative support, AI chatbots can assist with professional communication. Social media platforms such as Facebook, X, and LinkedIn are powerful tools for cardiologists, providing them with a platform to discuss important clinical and research topics and promote their work. However, managing them can be time consuming. AI chatbots can generate posts, draft content, and even create social media plans based on predefined objectives.

Cardiologists are often reluctant to seek professional mental health support for various reasons, including fear of stigma. Although AI chatbots are not “licensed therapists,” they can provide an easy, accessible, and non-judgmental space for emotional support by generating human-like conversations in response to user inputs. Instant messaging with AI offers cardiologists a convenient and stigma-free way to express their thoughts and emotions. While early reports suggest benefits from chatbot-based mental health support, further research is needed to validate their effectiveness; moreover, regulations on privacy are required to ensure compliance with health information laws.

AI chatbot integration must adhere to the principle of “first, do no harm.” The medical accuracy and reliability of AI chatbots in the field of cardiology is highly variable, as research validating their clinical impact is still in its infancy. Clinician oversight when using AI chatbots for decision making in a professional setting is always necessary. ChatGPT and other similar LLMs are currently not HIPAA compliant, hence, only de-identified protected health information can be submitted for analysis to ensure patient confidentiality. A cardiologist should avoid sharing personal or sensitive information, especially regarding sensitive tasks like finance, law, or health-related advice.

Like other advanced technologies, AI chatbots can be a double-edged sword. Cardiologists in any stage of their career could use AI chatbots to improve efficiency but should also maintain close oversight to avoid errors or system dependence.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Michaella Alexandrou, MD1; Dimitrios Strepkos, MD1; Arun Mahtani, MD2; Yader Sandoval, MD1; Emmanouil S. Brilakis, MD, PhD1

From the 1Minneapolis Heart Institute and Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, Abbott Northwestern Hospital, Minneapolis, Minnesota; 2Richmond University Medical Center/Mount Sinai, Staten Island, New York.

Acknowledgments: The authors are grateful for the philanthropic support of our generous anonymous donors (2), and the philanthropic support of Drs. Mary Ann and Donald A Sens; Mrs. Diane and Dr. Cline Hickok; Mrs. Wilma and Mr. Dale Johnson; Mrs. Charlotte and Mr. Jerry Golinvaux Family Fund; the Roehl Family Foundation; the Joseph Durda Foundation; Ms. Marilyn and Mr. William Ryerse; Mr. Greg and Mrs. Rhoda Olsen. The generous gifts of these donors to the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation’s Science Center for Coronary Artery Disease (CCAD) helped support this research project.

Disclosures: Dr Sandoval is a consultant for and on the advisory board of Abbott and GE Healthcare; is a consultant for, on the advisory board of, and a speaker for Phillips and Roche Diagnostics; is on the advisory board of Zoll; is a consultant for CathWorks; is a speaker for HeartFlow; is a speaker for and receives research grants from Cleerly; is an associate editor for JACC Advances; and holds patent 20210401347. Dr. Brilakis reports consulting/speaker honoraria from Abbott Vascular, American Heart Association (associate editor, Circulation), Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Cardiovascular Innovations Foundation (Board of Directors), Cordis, CSI, Elsevier, GE Healthcare, Haemonetics, IMDS, Medtronic, SIS Medical, Teleflex, and Orbus Neich; research support from Boston Scientific and GE Healthcare; is the owner of Hippocrates LLC; and is a shareholder for LifeLens Technologies, Inc, MHI Ventures, Cleerly Health, Stallion Medical, and TrueVue Inc. The remaining authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Address for correspondence: Emmanouil S. Brilakis, MD, PhD, Minneapolis Heart Institute, 920 E 28th Street #300, Minneapolis, MN 55407, USA. Email: esbrilakis@gmail.com; X: @CCAD_MHIF, @esbrilakis, @m1chaella_alex

References

1. Sharma A, Medapalli T, Alexandrou M, Brilakis E, Prasad A. Exploring the role of ChatGPT in cardiology: a systematic review of the current literature. Cureus. 2024;16(4):e58936. doi:10.7759/cureus.58936

2. Alexandrou M, Mahtani AU, Rempakos A, et al. Performance of ChatGPT on ACC/SCAI Interventional Cardiology Certification Simulation Exam. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17(10):1292-1293. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2024.03.012

3. Kumar A, Wang H, Muir KW, Mishra V, Engelhard M. A cross-sectional study of GPT-4–based plain language translation of clinical notes to improve patient comprehension of disease course and management. NEJM AI. 2025;2(2). doi:10.1056/AIoa2400402

4. Ayers JW, Poliak A, Dredze M, et al. Comparing physician and artificial intelligence chatbot responses to patient questions posted to a public social media forum. JAMA Intern Med. 2023;183(6):589-596. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.1838

5. Ng JY, Maduranayagam SG, Suthakar N, et al. Attitudes and perceptions of medical researchers towards the use of artificial intelligence chatbots in the scientific process: an international cross-sectional survey. Lancet Digit Health. 2025;7(1):e94-e102. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(24)00202-4