Effect of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Program Rankings on Case Selection

Since transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has become the standard therapy for severe symptomatic aortic stenosis in the United States, various rating systems have been developed to evaluate post-procedure outcomes. The two that are most commonly used are the STS/ACC TVT Star Rating System, introduced in 2022, and the US News and World Report (USNWR) ratings, introduced in 2020. While ranking systems help patients make informed decisions about their health care needs, evidence suggests that these ratings may have unintended and detrimental consequences on patient selection by incentivizing risk-avoidant behavior.

Background

Though not introduced for TAVR until recently, public reporting in cardiology and cardiac surgery itself is not a new concept and, in fact, throughout its implementation has produced consistent effects. In the 1990s, Pennsylvania’s publication of coronary artery bypass graft outcomes led to decreased procedure rates among high-risk and Black patients. Similar trends were seen in percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) in states like Massachusetts and New York, where the introduction of public ratings led to a reduction in the amount of PCI performed in patients with cardiogenic shock, a traditionally high-risk population.

The USNWR categorizes hospitals as high performing, average, or below average based on publicly available Medicare data. Unlike the opt-in STS/ACC TVT system, these ratings are reported for all hospitals. They use 3 general categories: facility characteristics, such as TAVR volume; process measures, such as the percentage of health care personnel who received timely flu vaccination; and outcomes measures, such as 30-day mortality. The final rating reflects a composite of these 3 scores plus a risk adjustment for the individual characteristics of the patients.

Because the USNWR ratings were introduced in a specific year, 2020, they can be used as a kind of naturalized experiment to assess the effect of public reporting.

Study Design

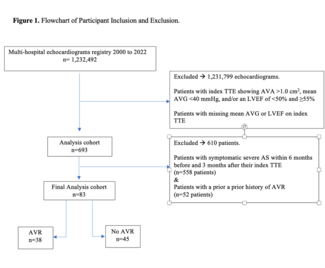

A difference-in-difference (DiD) design was used to test the hypothesis that lower-rated hospitals in the 2020 USNWR would exhibit more risk-averse behavior once the report was published. The study examined hospital case selection from 2015 to 2021, divided into a pre-period (2015-2019) and post-period (October 2020-December 2021). The first months of 2020 were excluded.

The relative risk, the change, and patient risk were evaluated using the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, the same assessment used by the USNWR. The study grouped hospitals into 2 cohorts: high performers and average/below average.

The DiD framework compares changes over time between 2 groups with an initial baseline difference. Both groups are expected to evolve—such as a shift in TAVR patient risk profiles—resulting in overall risk reduction over time. However, if an intervention affects 1 group differently, there will be a difference in that group. The DiD estimator captures the gap between the expected future, what “would have been,” had the intervention not been implemented, and what actually happened since the intervention, the system “shock,” took place.

Key Findings

The DiD model showed that, at baseline, the average and below-average risk hospitals treated higher-risk patients by about 0.23 points. After the introduction of the USNWR ratings, a 0.5% difference in the predicted Elixhauser risk of a patient was seen, which was above what was projected in the absence of the intervention. So, before the ratings, poor performing hospitals performed TAVR on sicker patients than higher performing hospitals; after the ratings were released, all hospitals performed TAVR on less sick patients. However, the shift was significantly greater among lower-rated hospitals, which is highly indicative of active risk-avoidant behavior in this group as a direct result of the ratings.

Takeaways

These findings highlight the paradox of public metrics. While designed to improve quality and help patients, such ratings may deter care for those most in need; the high-risk patients who stand to benefit most from TAVR may be, and are, turned away because of hospitals’ fear of poor outcome statistics. Moreover, the information used by the USNWR is inadequate in that it is based solely on Medicare claims data. This means that it does not take into account influential factors such as ventricular risk, lab results, and clinical presentation, which leads to incomplete risk adjustment.

Dr Nathan concluded with the following food for thought: “Should we focus more on the disease than the procedure? Should we think more about the treatment of aortic stenosis in general? But finally, and thought provoking, should we as a field participate in quality metrics? They're inadequate, they generate perverse incentives, and they frankly result in patient harm.”

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.