Sex Differences and the Role of Anemia in Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Journal of Invasive Cardiology or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Many, though not all, studies suggest that contrast-associated acute kidney injury (CA-AKI) after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) rates are higher in women. The authors sought to clarify the presence of and factors contributing to possible sex differences. Among 2971 consecutive patients undergoing PCI, women experienced higher crude rates of CA-AKI. However, this association was significantly attenuated after adjusting for demographic and comorbid conditions, particularly pre-procedural anemia, which accounted for a substantial proportion of the excess risk. The study offers clarification regarding the higher post-PCI risks among women and underscores the role of anemia as a prevalent contributor to CA-AKI.

Introduction

Contrast-associated acute kidney injury (CA-AKI) is a common complication, occurring after approximately 15% of all percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs).1 Many, though not all, prior studies suggest that CA-AKI rates are higher in women than in men, though female sex has not been traditionally incorporated into risk scores.2-5 We sought to clarify the presence of and factors contributing to potential sex differences in risks for CA-AKI following PCI in a real-world practice setting.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed all eligible PCIs performed at our institution from January 1, 2020 through December 31, 2023, excluding patients who received multiple same-day PCIs (n = 211) or who had missing peri-procedural creatinine data or pre-PCI dialysis requirement (n = 3898). We extracted data on patient demographics (age, race, and ethnicity), cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, peripheral artery disease, heart failure [HF], hyperlipidemia, pulmonary disease, history of myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, anemia, baseline glomerular filtration rate [GFR], and tobacco use), procedural factors (bleeding, contrast volume, fluoroscopy time, and cardiovascular instability), and health insurance status; anemia was defined as a pre-procedural hemoglobin of less than 10 g/dL.4 Per the National Cardiovascular Data Registry criteria, CA-AKI was defined as a post-PCI creatinine rise of greater than or equal to 0.3mg/dL or greater than or equal to 50% from baseline, or a new dialysis requirement. We used serial multivariable-adjusted logistic regression models to evaluate for sex-associated CA-AKI risk and identify factors contributing to any observed sex difference. The study protocol was approved by the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Institutional Review Board with a waiver for informed consent. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 18.0 (StataCorp) and P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. The analysis and manuscript preparation followed STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines.

Results

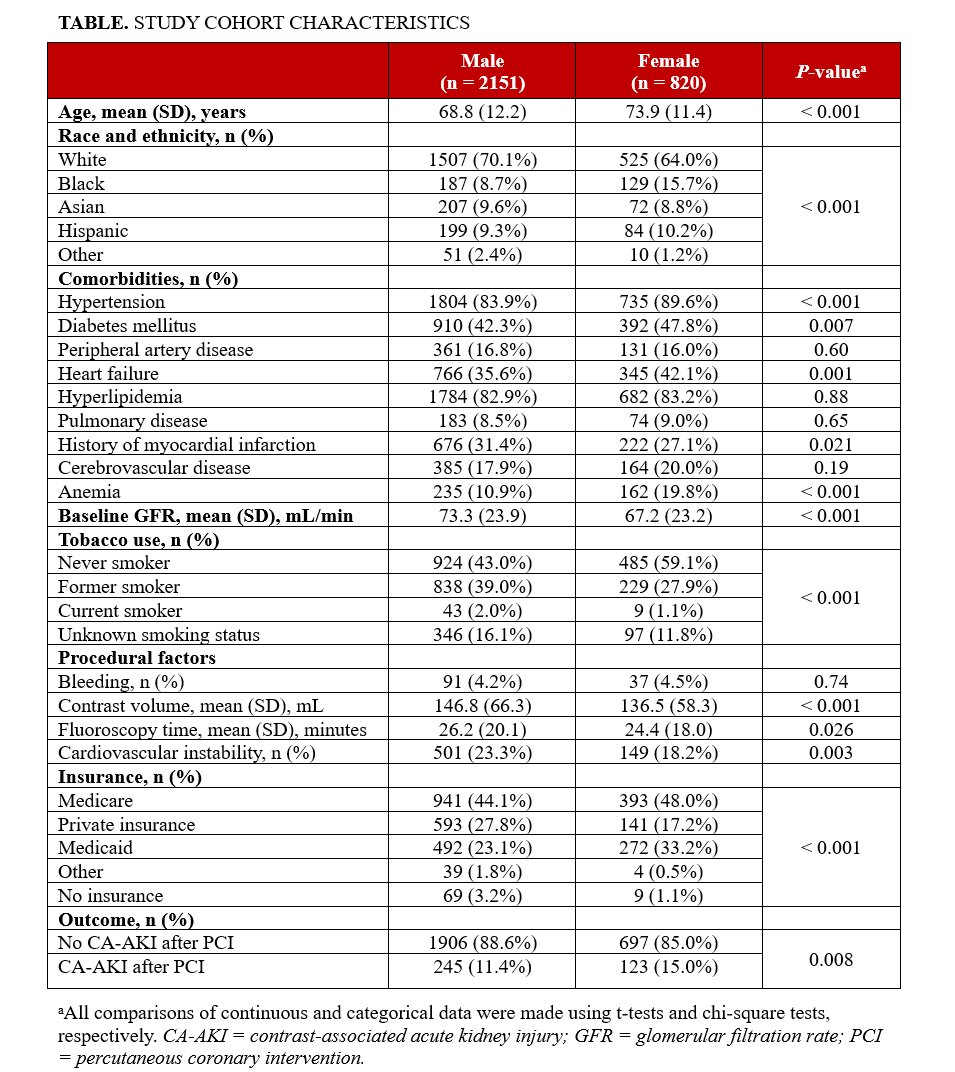

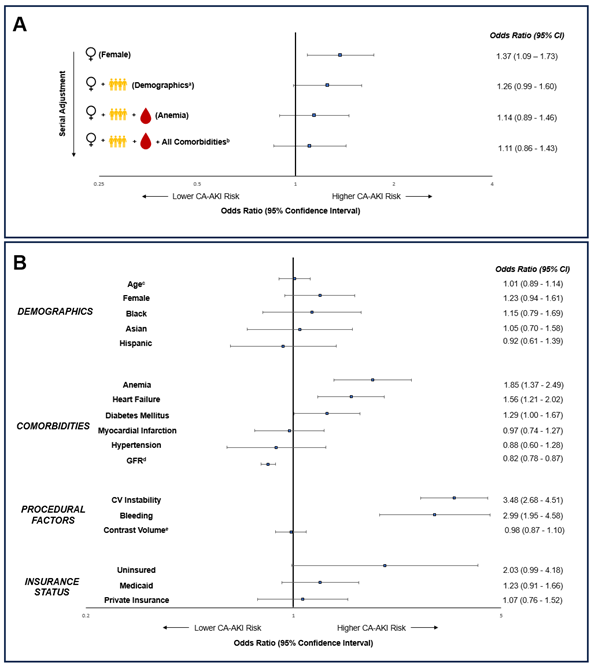

Of 2971 eligible PCIs, 820 (27.6%) were performed in women; the women were on average older than men, with a lower baseline GFR and more frequent hypertension, diabetes, HF, and anemia (Table). In unadjusted analyses, women experienced CA-AKI more frequently than men (15.0% vs 11.4%, P = .008), with an odds ratio of 1.37 (95% CI, 1.09-1.73). Adjustment for demographics (age, race, and ethnicity) attenuated this association (1.26 [0.99-1.60]), accounting for approximately 30% of the observed sex difference (Figure A). Further adjustment for anemia, in addition to demographics, reduced the association between CA-AKI and female sex again (1.14 [0.89-1.46]), accounting for approximately 60% of the sex difference. Adjustment for demographics and all included comorbidities (including anemia) accounted for approximately 75% of the sex difference (1.11 [0.86-1.43]). Additional adjustment for procedural factors and insurance status resulted in only negligible changes in CA-AKI/sex associations. In the final model, diabetes, HF, anemia, bleeding, and cardiovascular instability were associated with CA-AKI (P < .05 for all, Figure B). Baseline GFR was inversely associated with CA-AKI (P < .001).

Discussion

Among patients undergoing PCI, women experienced higher crude rates of CA-AKI than men. However, this association was significantly attenuated after adjusting for demographic and comorbid conditions, particularly pre-procedural anemia, which accounted for a substantial proportion of excess risk. Prior studies have revealed a stronger association between anemia and AKI in women compared with men following cardiac surgery, suggesting the presence of sex-specific differences in sensitivity to anemia in settings such as surgical stress.6 In a post-PCI population, this may also include contrast-induced renal hypoxia.7 Declining levels of estrogen among older women may result in increased susceptibility to ischemic AKI compared with men.8-10 Further investigations are needed to understand the extent to which the physiologically lower hemoglobin levels in women than men may contribute to observed sex-divergent risks for AKI following percutaneous and surgical procedures that are frequently undertaken in the management of common cardiac conditions.

Limitations

Our study limitations included the single-center design based at a quaternary-care hospital with high-volume PCI experience, which may limit generalizability. Excluding patients with pre-procedural dialysis or missing peri-procedural creatinine may have introduced selection bias, although women were less likely to be missing creatinine values. We were unable to exclude repeat PCIs received by individual patients over more than a 1-day period, which may have led to a unit-of-analysis bias. Several additional factors, such as anemia by World Health Organization definitions, access site, and pre-procedural CA-AKI prophylaxis strategy, were not available for inclusion in our model.

Conclusions

The factors that predispose to post-procedural CA-AKI have been historically difficult to assess because of the complex inter-relations between often coexisting risk traits in clinical practice. Our study offers clarification regarding the higher risks frequently seen in women following PCI and underscores the role of anemia as a pathophysiologically important and prevalent contributor to CA-AKI. Further, the results of our study can inform providers’ shared decision-making conversations when counseling patients, particularly women, on the risks of PCI.

Affiliations and Disclosures

Neil Zhang, MD, MS1; Kyla Sherwood, MD, MS2; Brian Claggett, PhD3; Sanket Dhruva, MD, MHS4; Ashishdeep Sandhu, MLS(ASCP)CM5; Susan Cheng, MD, MSc, MPH1; Joseph Ebinger, MD, MS1

From the 1Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California; 2David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California; 3Cardiovascular Division, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; 4Section of Cardiology, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center, San Francisco, California; 5Biome Analytics, San Francisco, California.

Disclosures: The authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Funding: This work was supported in part by NIH grant K23-HL153888 and NIH grant T32 HL116273. No funders had a role in the design/conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Address for correspondence: Joseph Ebinger, MD, MS, Department of Cardiology, Smidt Heart Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Email: cda-research@cshs.org

References

1. McCullough PA, Choi JP, Feghali GA, et al. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(13):1465-1473. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.099

2. Sidhu RB, Brown JR, Robb JF, et al. Interaction of gender and age on post cardiac catheterization contrast-induced acute kidney injury. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102(11):1482-1486. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.07.037

3. Mehran R, Owen R, Chiarito M, et al. A contemporary simple risk score for prediction of contrast-associated acute kidney injury after percutaneous coronary intervention: derivation and validation from an observational registry. Lancet. 2021;398(10315):1974-1983. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02326-6

4. Tsai TT, Patel UD, Chang TI, et al. Contemporary incidence, predictors, and outcomes of acute kidney injury in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions: insights from the NCDR Cath-PCI registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7(1):1-9. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2013.06.016

5. Gurm HS, Seth M, Kooiman J, Share D. A novel tool for reliable and accurate prediction of renal complications in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(22):2242-2248. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.026

6. Ripoll JG, Smith MM, Hanson AC, et al. Sex-specific associations between preoperative anemia and postoperative clinical outcomes in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2021;132(4):1101-1111. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000005392

7. Li WH, Li DY, Han F, Xu TD, Zhang YB, Zhu H. Impact of anemia on contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. Int Urol Nephrol. 2013;45(4):1065-1070. doi:10.1007/s11255-012-0340-8

8. Metcalfe PD, Meldrum KK. Sex differences and the role of sex steroids in renal injury. J Urol. 2006;176(1):15-21. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00490-3

9. Gallagher PG. Disorders of erythrocyte hydration. Blood. 2017;130(25):2699-2708. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-04-590810

10. Li X, Chen Q, Yang X, et al. Erythrocyte parameters, anemia conditions, and sex differences are associated with the incidence of contrast-associated acute kidney injury after coronary angiography. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1128294. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2023.1128294