Immunotherapy at the End of Life

Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have transformed cancer treatment, offering improved survival and tolerability compared with chemotherapy. However, their use at the end of life (EOL) raises concerns about clinical benefit, cost, and immune-related adverse events (irAEs). This retrospective study reviewed 641 patients treated with ICIs at Scripps Clinic who died between June 2017 and August 2023. Demographics, cancer types, treatment timelines, and causes of death were analyzed, with a focus on EOL care. No patients received immunotherapy within the last 30 days of life. Time from last treatment to death varied by cancer type, with breast cancer patients showing the longest interval and gastrointestinal cancers the shortest. irAEs occurred in 28% of patients, mostly grades 2–3. Patients who died from irAEs had significantly shorter intervals between last treatment and death (mean, 34 days), and most were receiving monotherapy. Smoking history was associated with more severe irAEs. These findings underscore the need for cautious, patient-centered decision-making regarding ICI use at EOL, including timely treatment discontinuation, smoking cessation counseling, and integration of palliative care. Prospective studies are needed to evaluate the impact of ICIs on quality of life and EOL cancer care.

Introduction

Chemotherapy given at the end of life (EOL) has not been shown to improve either survival or quality of life.1 Near the EOL, patients on systemic chemotherapy are less likely to enter hospice and more likely to require acute medical care, including emergency department visits, intensive care unit admissions, and hospital deaths.2-10 The advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has markedly advanced oncology, extending both progression-free and overall survival in different cancers.11 For adults with impaired performance status, ICIs present a potential therapeutic option, as their side-effect profile is generally more tolerable than that of standard chemotherapy.12 While the impact of chemotherapy at the EOL is well documented, much less is known about immunotherapy in this context. It has been shown that immunotherapy use in EOL has been increasing over time since its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for various cancers, including melanoma in 2012 as well as both kidney cell carcinoma and non–small cell lung cancer in 2016.13 ICIs are currently approved to treat approximately 18 different cancer types.14 With its expanded use, there is a growing need for further research in this specific setting. Prior analysis has found a negative association between ICI use in EOL and poorer performance status, decreased hospice enrollment, and increased financial toxicity while providing minimal clinical benefit.15

ICIs are commonly associated with immune-related adverse events (irAEs), which occur when the immune system attacks various organs and healthy tissue. irAEs range from minimally symptomatic (grade 1) to potentially life-threatening (grade 4).16 Several studies suggest that a history of smoking may increase the risk for developing irAEs.17

This study sought to analyze the patterns of immunotherapy use at Scripps Clinic and to assess whether ICIs were continued despite disease progression. Immunotherapy use after confirmed disease progression may delay timely hospice referrals and increase health care costs by extending treatments with diminishing clinical benefit. Additionally, this study sought to determine whether immunotherapy use in EOL cancer care exacerbates mortality outcomes. If so, this emphasizes the importance of a more cautious and patient-centered approach to treatment decisions during this critical phase. We conducted a retrospective review of patient characteristics and outcomes, with particular attention to EOL factors.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Scripps Clinic is a community-based teaching institution with a strong focus on subspecialty care. Using the Scripps Clinic electronic medical records database, we retrospectively reviewed records of patients with cancer who were treated with immunotherapy and died between June 1, 2017, and August 30, 2023. In this study, “near EOL” was defined as the period of time leading up to the patient’s death during which continued systemic therapy may have offered limited clinical benefit or the point beyond which cytotoxic chemotherapy would be contraindicated.

Variables

The following patient characteristics were collected and reviewed: age, sex, race, smoking history, cancer type, immunotherapy agent used (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, ipilimumab, durvalumab, cemiplimab, and atezolizumab), dates of immunotherapy initiation and death, and cause of death.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for demographic and clinical data are reported as means and standard deviation for continuous data and as frequency (n) and percentage for categorical data. Exploratory analyses using t tests and one-way analysis of variance tests (ANOVAs) were conducted to evaluate differences by age (defined at 70 years, median age), ethnicity, race, sex, cancer type, region defined by the San Diego Health and Human Services Agency (HHSA), immunotherapy agents, and cause of death on the following variables: days from diagnosis to death, time from last treatment to death, and time between first and last treatment.18

Variables with more than two factors were evaluated by a one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey tests were conducted to correct for multiple comparisons. Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess associations in the demographic and clinical factors (age, sex, race, ethnicity, cancer type, immunotherapy, HHSA regions, and cause of death) and survival for time from diagnosis to death. Hazard ratios are shown with respect to the reference group with 95% CIs. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05. All analyses were conducted in R version 4.3.3.19

Results

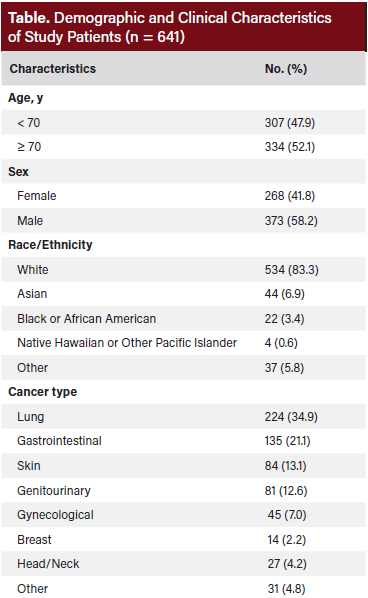

The Table outlines the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohort, comprising a total of 641 individuals. Among this cohort, 268 (42%) participants were female, 373 (58%) were male, and most (83.3%) identified as White. Lung (35%), gastrointestinal (21%), skin (13%), genitourinary (12.6%), and other malignancies (19.4%) were the most frequently observed tumor types. Immunotherapy was not administered to any patient during the last 30 days of life.

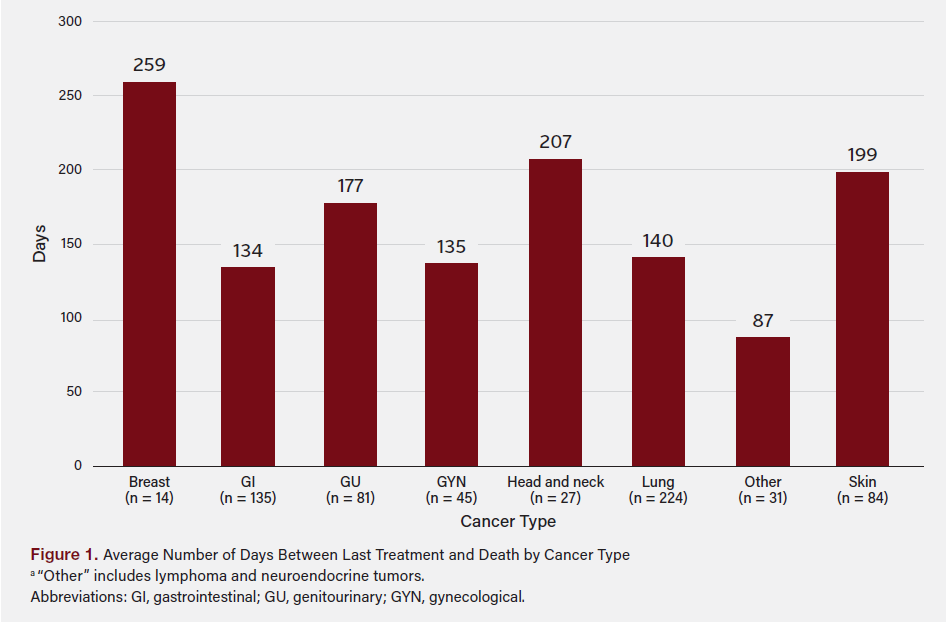

Figure 1 shows the average number of days between last treatment and death by cancer type. Among cancer types, patients with breast cancer had the longest mean duration from final treatment to death, averaging 259 ± 338 days. Most patients (11 out of 14) were receiving treatment with palliative intent. Following breast cancer, the longest intervals from last treatment to death were observed in head and neck cancer (207 ± 387 days), skin cancer (199 ± 301 days), genitourinary cancers (177 ± 254 days), lung cancer (140 ± 224 days), gynecologic cancers (135 ± 162 days), and gastrointestinal cancers (134 ± 181 days). A total of 180 patients (28%) experienced irAEs, with most classified as grade 2 or grade 3. Current smokers and former smokers experienced more severe grade irAEs compared with never-smokers (38% vs 22%; P = .0065).

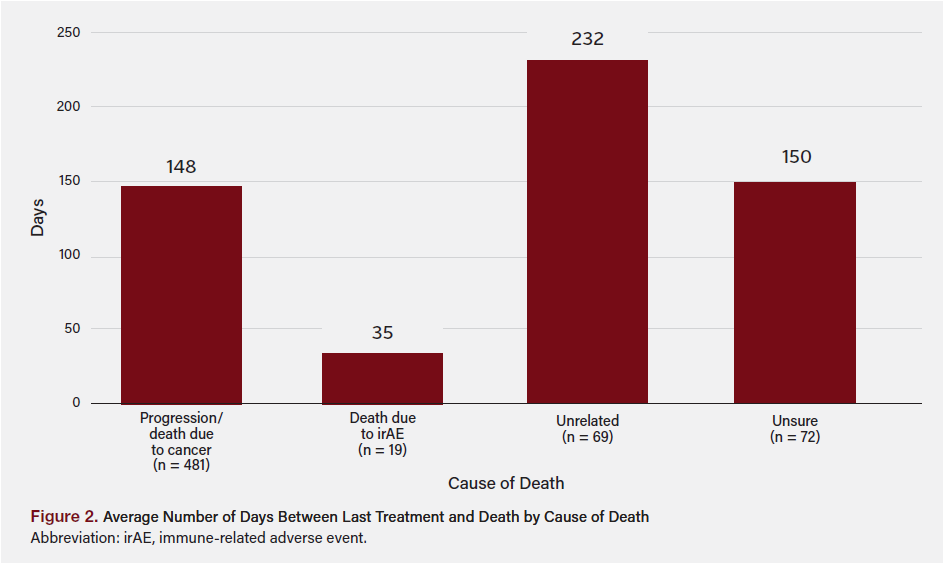

Figure 2 shows the average number of days from last treatment and death by the cause of death. A total of 19 patients (3%) died from irAEs, 17 of whom (89%) were receiving monotherapy at EOL. Patients in this group had the briefest duration between last treatment and death (34 ± 24 days), followed by those who died from cancer progression, with an average interval of 148 ± 212 days.

Discussion

This study evaluated the use and impact of immunotherapy at EOL in patients with various cancer types at Scripps Clinic. Recognizing that chemotherapy given to patients with poor performance status can shorten rather than extend life, this study examined immunotherapy treatment patterns, timing of therapy cessation, and causes of death to clarify how immunotherapy is being applied in practice and to identify opportunities for more cost-effective care. Analysis found that there was a difference in time intervals between last immunotherapy treatment and death depending on cancer type. Breast cancer patients had the longest interval, followed in order by head and neck, skin, genitourinary, lung, gynecologic, and gastrointestinal cancers, which had the shortest interval. Of note, the efficacy of ICIs varies significantly across cancer types. For example, malignancies such as melanoma and non–small cell lung cancer often respond more favorably to treatment, while others, including gastrointestinal cancers, tend to be less efficacious.20-22 Also, some malignancies use ICI more often than others.23,24 In patients with breast cancer, ICIs are approved only for triple-negative disease, which accounts for approximately 15% of all invasive breast cancers.25-27 Our data showed that those with gastrointestinal cancers (HR, 1.753; 95% CI, 1.001-3.069; P = .0495) and lung cancer (HR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.121-3.358; P = .0179) had a statistically significant higher hazard of death compared to those with breast cancer. This is consistent with the literature that prognosis remains poor for many cancer types, including metastatic esophageal and gastric cancers.28,29

Our study revealed significant variability in the interval between the last immunotherapy treatment and death based on the cause of death. There was a longer interval between administration of ICI and death due to cancer progression (148 days). This reflects the chronic and gradual trajectory of disease advancement and is consistent with findings by Petrillo et al,12 who observed that patients with advanced cancer treated with ICIs experienced prolonged survival compared with those receiving standard chemotherapy, including at the EOL. In contrast, patients who died due to irAEs experienced the shortest interval, averaging 34 days. This rapid decline starkly contrasts with patients whose deaths were primarily attributed to cancer progression. In our study, 28% of patients experienced an irAE, which is lower than the approximately 39% incidence reported in a prior meta-analysis comprising 147 studies.30

ICI therapy can be given as monotherapy, in combination with chemotherapy or dual-ICI. Some tumor types, such as melanoma, recommend dual-ICI while others, such as gastrointestinal malignancies, recommend only single-agent ICI.31,32 How ICI therapy is prescribed can impact the severity of an irAE. Our study found that most patients who died from irAEs were receiving monotherapy ICI, which contrasts notably with existing literature. Numerous meta-analyses and cohort studies consistently report significantly higher rates and severity of irAEs with dual-agent ICI compared with monotherapy, including increased hospitalization and emergency department use.33-36

Potential explanations for our findings include larger numbers of patients on monotherapy, variations in patient selection or clinical management practices, differences in timing of event detection, and confounding variables, including patient baseline health status. Balaji et al37 reported that hospitalizations due to severe irAEs often preceded swift clinical decline, highlighting the need for early recognition and aggressive treatment to mitigate fatal outcomes. Whether immunotherapy is given as monotherapy or dual, when a patient experiences a high-grade irAE, there is often rapid deterioration. Therefore, it is crucial that irAEs are identified and managed urgently. Although ICIs offer promising outcomes in many cases, their use requires careful patient monitoring.

There are many other factors that contribute to death while receiving ICI aside from irAEs. These include older age, increased number of medical comorbidities, and greater burden of metastatic disease.13 Our data support that there is a significant difference in hazard of death for those aged 70 years and older (HR, 1.452; 95% CI, 1.24-169; P < .001). Other factors can worsen irAEs, such as cigarette smoking, which may be due to its pro-inflammatory effects.17,37-42 Our study supported that current and former smokers experienced more severe irAEs compared with never-smokers. However, the relationship between smoking history and irAEs remains a topic of debate, as some earlier research found no significant association.43,44 Providers should counsel patients on the potential impact of smoking on the severity of irAEs during immunotherapy and reinforce the health benefits of smoking cessation to potentially mitigate these treatment-related risks.

Limitations

This study was conducted at a single center and included a predominantly White population (83%), which may limit the generalizability of the findings to more diverse settings. Additionally, the retrospective nature of the data collection introduces the potential for selection bias and depends on the accuracy and completeness of medical records, which could affect the reliability of the results. The relatively small sample size further limits the study’s statistical power, particularly for subgroup analyses.

Conclusion

This study aimed to highlight patterns of ICI use and examine whether extended treatment beyond poor performance status and disease progression increases adverse outcomes. Our study found irAEs in 28% of patients, highlighting the need for a prospective trial to evaluate immunotherapy’s impact on quality of life and cost. Our findings emphasized the importance of adopting a cautious and mindful approach to ensure ICI treatment decisions align with patient-centered care and optimal outcomes during EOL, which was reflected in our practice. Because ICIs are the standard of care in treating many malignancies, it is challenging to define when immunotherapy transitions from an evidence-based continuation of care to an EOL intervention. However, in patients with disease progression, further ICI administration may confer diminishing benefit and overall increase in health care spending. Oncologists should prioritize thorough discussions about immunotherapy with their patients, emphasize the importance of smoking cessation when applicable, ensure vigilant monitoring for irAEs, and carefully evaluate the timing of treatment discontinuation to ensure best possible patient outcomes. These conversations should also incorporate performance status, disease trajectory, psychosocial goals, and financial burden, ideally within a structured decision-making framework that integrates palliative care and multidisciplinary input. Our results may reflect a subspecialized approach to oncology care that differs from both general community-based practices and academic medical centers.

Clinical Pathway Category: Palliative & End-of-Life Care

This study supports the palliative & end-of-life care clinical pathway category by emphasizing timely discontinuation of immune checkpoint inhibitors and integration of palliative services near the end of life. By providing evidence on the limited benefit and potential risks of late-stage immunotherapy, the study aligns with evidence-based standards to guide patient-centered, value-conscious oncology care that optimizes quality of life and minimizes harm.

Author Information

Authors: Gagandeep Kaur, DO1; Havi Rosen, MD1; Luke Shenton, MD1; Terrence Sun, DO1; Abigail Mackenzie, MD1; Leah Puglisi, MS3; Catherine Weir, DO2; Marin Feldman Xavier, MD2; Diana Vesselinovitch Maslov, MD2

Affiliations: 1Scripps Mercy Hospital, San Diego, CA; 2Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, CA; 3Department of Research & Development, Scripps Health, San Diego, CA

Address correspondence to:

Gagandeep Kaur, DO

Scripps Mercy Hospital, San Diego, CA

E-mail: kaur.gagandeep@scrippshealth.org

Acknowledgments: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences under grant number UM1TR004407.

Disclosures: The authors disclose no financial or other conflicts of interest.

References

1. Riaz F, Gan G, Li F, Davidoff AJ, et al. Adoption of immune checkpoint inhibitors and patterns of care at the end of life. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16(11):e1355-e1370. doi:10.1200/OP.20.00010

2. Bao Y, Maciejewski RC, Garrido MM, Shah MA, Maciejewski PK, Prigerson HG. Chemotherapy use, end-of-life care, and costs of care among patients diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;55(4):1113-1121.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.12.335

3. Beaudet ME, Lacasse Y, Labbe C. Palliative systemic therapy given near the end of life for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(3):1316-1325. doi:10.3390/curroncol29030112

4. Mallett V, Linehan A, Burke O, et al. A multicenter retrospective review of systemic anti-cancer treatment and palliative care provided to solid tumor oncology patients in the 12 weeks preceding death in Ireland. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021;38(12):1404-1408. doi:10.1177/1049909120985234

5. Mohammed AA, Al-Zahrani AS, Ghanem HM, Farooq MU, El Saify AM, El-Khatib HM. End-of- life palliative chemotherapy: where do we stand? J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2015;27(1):35-39. doi:10.1016/j.jnci.2015.02.001

6. Tsai HY, Chung KP, Kuo RN. Impact of targeted therapy on the quality of end-of-life care for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a population-based study in Taiwan. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(3):798-807e4. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.10.009

7. Zhu Y, Tang K, Zhao F, et al. End-of-life chemotherapy is associated with poor survival and aggressive care in patients with small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018;144(8):1591-1599. doi:10.1007/s00432-018-2673-x

8. Näppä U, Lindqvist O, Rasmussen B, Axelsson B. Palliative chemotherapy during the last month of life. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(11):2375-2380. doi:10.1093/annonc/ mdq778

9. Saito AM, Landrum MB, Neville BA, Ayanian JZ, Earle CC. The effect on survival of continuing chemotherapy to near death. BMC Palliat Care. 2011;10(1):14. doi:10.1186/1472-684X-10-14

10. Schulkes KJG, van Walree IC, van Elden LJR, et al. Chemotherapy and healthcare utilisation near the end of life in patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(2):e12796. doi:10.1111/ecc.12796

11. Bloom MD, Saker H, Glisch C, et al. Administration of immune checkpoint inhibitors near the end of life. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(6):e849-e856. doi:10.1200/ OP.21.00689.

12. Petrillo LA, El-Jawahri A, Nipp RD, et al. Performance status and end-of-life care among adults with non-small cell lung cancer receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer. 2020;126(10):2288-2295. doi:10.1002/cncr.32782

13. Kerekes DM, Frey AE, Prsic EH, et al. Immunotherapy initiation at the end of life in patients with metastatic cancer in the US. JAMA Oncol. 2024;10(3):342-351. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.6025

14. Carlisle JW, Steuer CE, Owonikoko TK, Saba NF. An update on the immune landscape in lung and head and neck cancers. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(6):505-517. doi:10.3322/caac.21630.

15. Glisch C, Saeidzadeh S, Snyders T, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor use near the end of life: a single-center retrospective study. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(7):977-979. doi:10.1089/jpm.2019.0383

16. Schneider BJ, Naidoo J, Santomasso BD, et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(36):4073-4126. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.01440

17. Suazo-Zepeda E, Bokern M, Vinke PC, Hiltermann TJN, de Bock GH, Sidorenkov G. Risk factors for adverse events induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2021;70(11):3069-3080. doi:10.1007/s00262-021-02996-3

18. Health & Human Services Agency. SanDiegoCounty.gov. Accessed October 24, 2025. www.sandiegocounty.gov/content/sdc/hhsa.html

19. R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2023. Available from: https://www.R-project.org

20. Longo V, Brunetti O, Azzariti A, et al. Strategies to improve cancer immune check-point inhibitors efficacy, other than abscopal effect: a systematic review. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(4):539. doi:10.3390/cancers11040539

21. Noori M, Jafari-Raddani F, Davoodi-Moghaddam Z, Delshad M, Safiri S, Bashash D. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in gastrointestinal malignancies: an umbrella review. Cancer Cell Int. 2024;24(1):10. doi:10.1186/s12935-023-03183-3

22. Puccini A, Battaglin F, Iaia ML, Lenz HJ, Salem ME. Overcoming resistance to anti-PD1 and anti-PD-L1 treatment in gastrointestinal malignancies. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1):e000404. doi:10.1136/jitc-2019-000404

23. Bagchi S, Yuan R, Engleman EG. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: clinical impact and mechanisms of response and resistance. Annu Rev Pathol. 2021;16:223-249. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-042020-042741

24. Gaynor N, Crown J, Collins DM. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: key trials and an emerging role in breast cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;79:44-57. doi:10.1016/j. semcancer.2020.06.016

25. Dvir K, Giordano S, Leone JP. Immunotherapy in breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(14):7517. doi:10.3390/ijms25147517

26. Villacampa G, Navarro V, Matikas A, et al. Neoadjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors plus chemotherapy in early breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2024;10(10):1331-1341. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2024.3456.

27. Elimimian EB, Samuel TA, Liang H, Elson L, Bilani N, Nahleh ZA. Clinical and demographic factors, treatment patterns, and overall survival associated with rare triple-negative breast carcinomas in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e214123. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4123.

28. Luo H, Lu J, Bai Y, et al. ESCORT-1st Investigators. Effect of camrelizumab vs placebo added to chemotherapy on survival and progression-free survival in patients with advanced or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: the ESCORT-1st randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326(10):916-925. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.12836

29. Li S, Yu W, Xie F, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy with immune checkpoint blockade, antiangiogenesis, and chemotherapy for locally advanced gastric cancer. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):8. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-35431-x

30. Shen X, Yang J, Qian G, et al. Treatment-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1391724. doi:10.3389/fonc.2024.1391724

31. Seth R, Agarwala SS, Messersmith H, et al. Systemic therapy for melanoma: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(30):4794-4820. doi:10.1200/JCO.23.01136

32. Shah MA, Kennedy EB, Alarcon-Rozas AE, et al. Immunotherapy and targeted therapy for advanced gastroesophageal cancer: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(7):1470-1491. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.02331

33. Da L, Teng Y, Wang N, et al. Organ-specific immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy versus combination therapy in cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Pharmacol. 2020;10:1671. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.01671

34. Gunturu KS, Pham TT, Shambhu S, Fisch MJ, Barron JJ, Debono D. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: immune-related adverse events, healthcare utilization, and costs among commercial and Medicare Advantage patients. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(5):4019-4026. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-06826-9

35. Jayathilaka B, Mian F, Franchini F, Au-Yeung G, IJzerman M. Cancer and treatment specific incidence rates of immune-related adverse events induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2025;132(1):51-57. doi:10.1038/s41416-024-02887-1

36. Reid P, Sandigursky S, Song J, et al. Safety and effectiveness of combination versus monotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with preexisting autoimmune diseases. Oncoimmunology. 2023;12(1):2261264. doi:10.1080/21 62402X.2023.2261264

37. Balaji A, Zhang J, Wills B, et al. Immune-related adverse events requiring hospitalization: spectrum of toxicity, treatment, and outcomes. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(9):e825-e834. doi:10.1200/JOP.18.00703

38. Su Z, Guan M, Zhang L, Lian X. Factors associated with immune‑related severe adverse events (review). Mol Clin Oncol. 2024;22(1):3. doi:10.3892/mco.2024.2798

39. Chennamadhavuni A, Abushahin L, Jin N, Presley CJ, Manne A. Risk factors and biomarkers for immune-related adverse events: A practical guide to identifying high-risk patients and rechallenging immune checkpoint inhibitors. Front Immunol. 2022;13:779691. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.779691

40. Hata H, Matsumura C, Chisaki Y, et al. A retrospective cohort study of multiple immune-related adverse events and clinical outcomes among patients with cancer receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Control. 2022;29:10732748221130576. doi:10.1177/10732748221130576

41. Uchida Y, Kinose D, Nagatani Y, et al. Risk factors for pneumonitis in advanced extrapulmonary cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:551. doi:10.1186/s12885-022-09642-w

42. Byrne MM, Lucas M, Pai L, Breeze J, Parsons SK. Immune-related adverse events in cancer patients being treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Haematol. 2021;107(6):650-657. doi:10.1111/ejh.13703

43. Pan C, Kim C, Lau D, et al. Effects of smoking status on incidence and severity of immune-related adverse events among patients with melanoma receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(3):AB155. Presented at: American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting; March 2023; New Orleans, LA.

44. Knox A, Cloney T, Janssen H, Solomon B, Alexander M, John T. Real-world incidence and outcomes of immune-related adverse events in NSCLC patients. Ann Oncol. 2023;34:S1684. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2023.10.629