Standardizing Somatic and Germline Molecular Testing in Prostate Cancer: Care Pathway and EHR Applications

Abstract

Clinical guidelines recommend tumor testing for patients with metastatic prostate cancer (mPC), but testing rates remain inconsistent across patient populations. To address this, we developed a care pathway and investigated opportunities to leverage the electronic health record (EHR) to standardize testing workflows and support practices in the United States. Using a modified Delphi methodology approach with a hybrid offline and live format, we conducted an online survey and panel discussion with live polling to identify opportunities for improvement and real-world implementation considerations. Based on the identified barriers, clinical guidelines, and real-world practices, we developed a care pathway and three clinical resources covering EHR applications. These tools guide the use of EHR automation to improve patient identification, enhance clinical decision-making, and optimize the integration of tumor and germline testing into clinical workflows across care settings. The results of this study may support practices in standardizing molecular testing and may reduce care inequities for patients with mPC.

Introduction

According to the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Statistics 2023 report, rates of advanced prostate cancer (PCa) have increased for the first time in 20 years.1 Data also show that the percentage of patients with distant-stage disease has doubled from 2014 to 2019.2 Notably, Black patients have a 70% higher incidence of advanced PCa compared with White patients, and their mortality rates due to this disease are approximately two to four times higher than those in all other racial and ethnic groups.2 Furthermore, a review article on disparities in advanced PCa germline testing reported that African American, Canadian, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Hispanic populations were often underrepresented in tested populations, clinical trials, and other studies.3 The variability in care and underrepresentation in research may drive and exacerbate the differences observed in outcomes across race and ethnicity.

Molecular testing offers transformative insights for treating clinicians, providing data to inform predisposition, prognosis, and treatment decisions. Broad panel molecular testing plays a critical role in understanding and treating metastatic prostate cancer (mPC), particularly due to the presence of actionable biomarkers in the homologous recombination repair (HRR) pathway. With the emergence of next-generation sequencing (NGS), it is now possible to test for multiple mutations simultaneously, identifying either those that are inherited (germline mutations) or those that develop spontaneously in tumors as the disease progresses (somatic mutations).

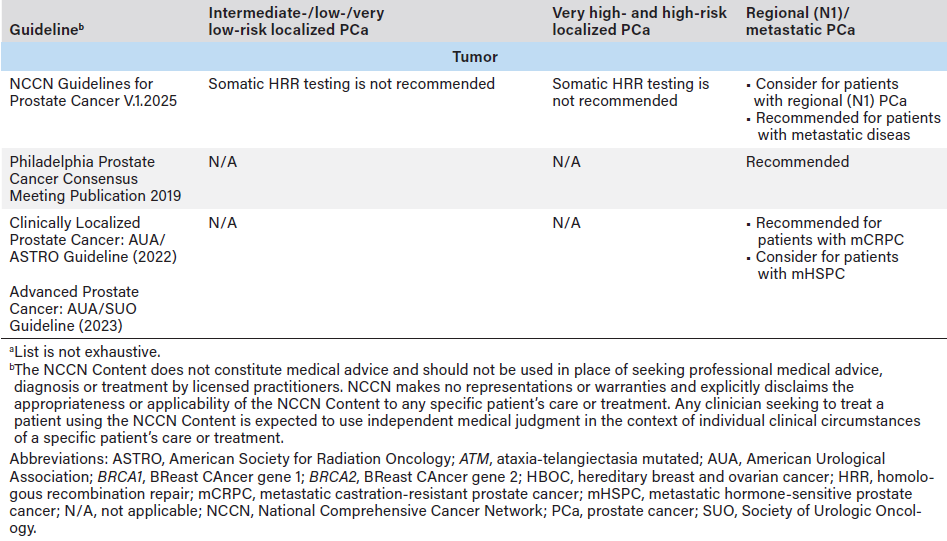

Current clinical guidelines—including those from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network® Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®), Philadelphia Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference 2019, American Urological Association (AUA), American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO), and the Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO)—recommend molecular tumor testing for all patients with mPC (Table 1).4-8 Germline testing is also recommended for patients with mPC if it has not previously been performed, based on family or personal history, before metastatic disease can be clinically diagnosed. Broad panel molecular testing supports informed treatment decision-making, including the expanding use of precision therapies, such as US Food and Drug Administration-approved poly adenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase inhibitors (PARPi). Despite strong consensus on molecular testing and clear clinical benefits of broad panel molecular testing, testing rates remain inconsistent.

This initiative proposes a Molecular Testing Care Pathway and applications of the electronic health record (EHR) to support broad panel molecular testing for patients with mPC, with specific consideration to typically available resources in community care settings. Molecular testing rates are reportedly lower in community oncology practices compared with academic oncology settings, where patients are more than twice as likely to receive testing.9 Achieving higher testing rates across all practices is important to ultimately reduce disparities in care observed across patient populations.

Overview of Barriers and Approaches to Integrating Broad Panel Molecular Testing for Care Teams in Current Literature

Care teams face many barriers to broad panel molecular testing along the care continuum, from identifying patients eligible for testing to maneuvering test ordering and interpreting results, that impede achieving current standards of care for patients with mPC.10

Clinical Workflow and Suggested Opportunities

Teams implementing clinical pathways should comprehensively assess workflows to identify opportunities for organization-specific interventions and systems of care.10 Multiple intervention points may exist depending on when the patient presents for care and when information becomes available. For example, decision support can be embedded in the ordering process through passive suggestions within an order set or with pop-up ordering alerts. Decision support should also be tailored to the specific stage of the disease process, whether it is for initial testing or subsequent treatment based on test results. In some cases, the patient may be present in the office, but retrospective review and follow-up methods may be required in other cases. Additionally, under the 21st Century Cures Act, patients have the right to access test results once their physician receives them.11 Therefore, diagnostic testing should be accompanied by relevant patient education.

Patient Identification and Providers’ Knowledge of Genetic Information

Guideline-concordant care is built on a foundation of identifying eligible patients for whom molecular testing is recommended. To do so effectively and promptly, it is critical that care teams understand the evolving guidelines related to molecular testing (both germline and tumor) for advanced PCa.10 Providers must be informed of recommendations on how to interpret results, how those results may affect treatment plans, and when retesting may be necessary.10

Genetic Counseling

Because broad panel molecular testing may potentially identify a germline mutation, it is important that patients are counseled on potential findings and results. However, access to genetic counselors is limited due to high demand.12 As a result, a hybrid practice model has emerged in which oncologists, urologists, and other providers conduct pretest counseling (including informed consent), order tests, and provide posttest counseling for tumor testing results.5 Yet, not all providers have the time, capacity, or genetic expertise to do so.

Sample Collection

Collecting and locating an adequate specimen in advanced PCa is nuanced. There is often a significant time gap (often many years) between the original diagnosis of advanced PCa and a metastatic diagnosis, which can make it difficult to obtain a testing sample.13,14 Additionally, genetic material taken from metastatic bone lesions for molecular testing have a relatively high rate of failure.15 Tissue biopsies are preferred, but they are invasive and pose a risk for tumor heterogeneity.16 If a radical prostatectomy was performed at the time of the initial diagnosis, the tissue sample may be unsuitable for future recommended molecular testing due to tissue age, storage issues, or changes in tumor biology. Alternatively, liquid biopsy using plasma has demonstrated clinical utility but requires an ample amount of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and may be less sensitive.15,17 For germline testing, saliva, plasma, or blood samples are typically sufficient for molecular testing.15

Genetic Information in EHRs

Integrating molecular test results into the EHR is complex, with technical limitations that hinder its potential to support clinical decision-making. Current EHR architecture systems struggle to link key data related to broad panel molecular testing, such as the patient, biologic specimen, test order, reference laboratory, and the ability to annotate results as either germline or somatic.14 Ensuring results are formatted in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)- compliant manner is also critical for clinical utility. EHRs lack provider alerts for critical information, such as qualifying status and relevant mutations, further hindering optimal care. If a patient is referred to another practice, loading patient information into structured data fields within the EHR when feasible can facilitate the transfer of patient information and molecular testing results.

Variation in Prayer Coverage

Coverage varies across commercial payers and continues to evolve as guidelines expand. Patients require transparent and straightforward information about insurance criteria to understand the associated costs and requirements for prior authorization and documentation related to germline and tumor testing. Many commercial payers and Medicare reference NCCN Guidelines to determine coverage criteria. In 2018, the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a national coverage determination to reimburse molecular testing for beneficiaries with advanced or metastatic cancer who have had not previously undergone NGS testing.18 However, inconsistencies between guideline-recommended care and commercial payer policies persist.19

Overcoming Barriers to Care: Broad Panel Molecular Testing Care Pathway Toolkit

This initiative developed a Broad Panel Molecular Testing Care Pathway and EHR Toolkit for health care professionals to integrate molecular testing for mPC into standard practice. These resources offer actionable steps to improve patient identification, support clinical decision-making in a variety of care environments, and standardize guideline-concordant molecular testing practices. Their implementation can help reduce testing rate disparities and ensure that patients with mPC receive appropriate targeted treatment.

Methods

Set-up and Panel Composition

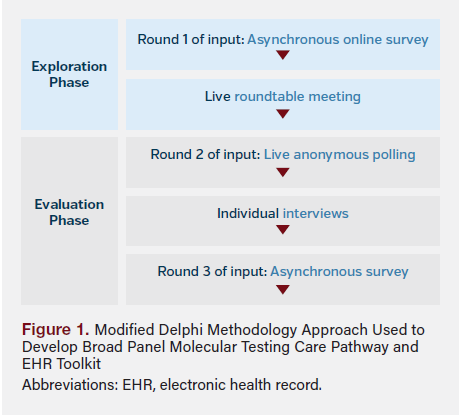

We used a modified Delphi methodology20 approach with a hybrid format of offline and live components to generate consensus on optimal care for patients with mPC, with a primary focus on broad panel molecular testing (Figure 1). The panel included nine participants from diverse administrative and clinical specialties (medical oncology, urology, laboratory testing, information technology, and payer services) and practice types (academic, community urology, and community oncology). All participants had more than 10 years of relevant experience, held advanced degrees (PharmD, MD, and/or MBA), and were nationally recognized by their work in research, publications, or speaker roles.

Steps

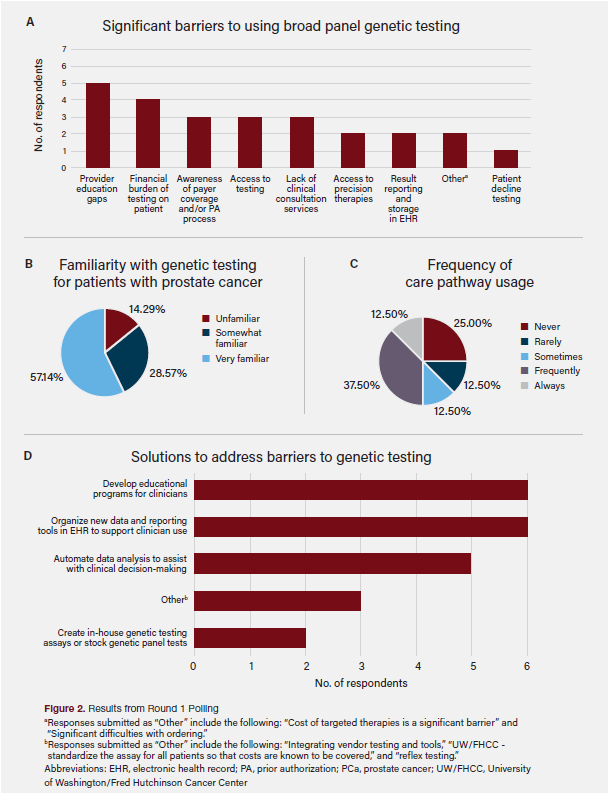

Participants first completed an asynchronous online survey that asked them to describe their use of a care pathway and familiarity with broad panel molecular testing using a Likert scale. Participants were then asked to identify common barriers and opportunities to increase molecular testing (N = 8; Figure 2). A roundtable meeting followed, where participants reached consensus on which barriers should be initially targeted to improve rates of molecular testing (N = 9).

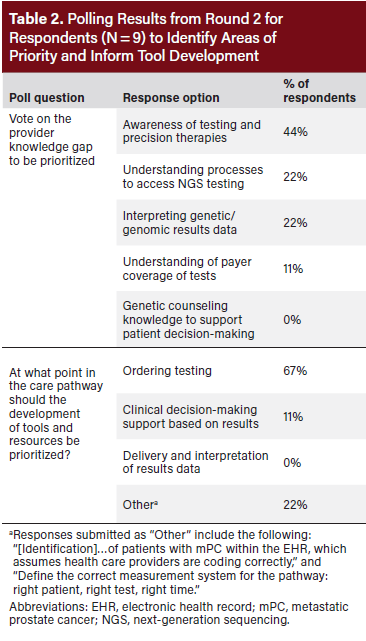

Participants were then asked live polling questions to build further consensus on barriers and operational steps to be included in the care pathway and identify opportunities for EHR application in patient identification (N = 9; Table 2). One-on-one interviews with participants (N = 8) provided further detail into shared individual learnings and expertise on the care pathway and resource components. Another round of asynchronous feedback (N = 8) was collected to confirm adjustments for real-world implementation.

Results

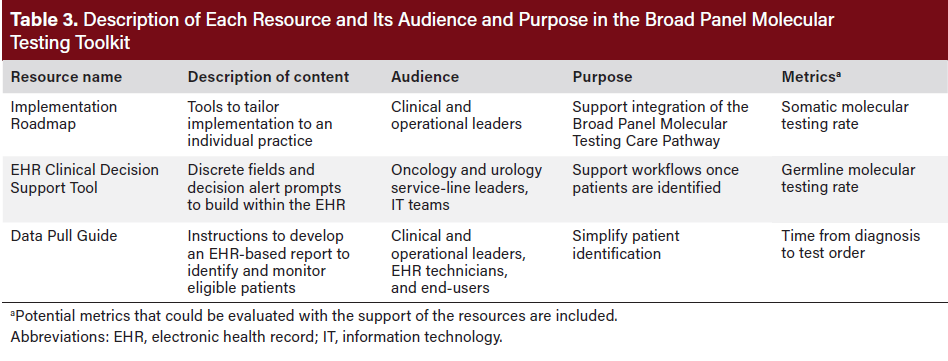

Consensus was reached, leading to the development of an evidence-based Broad Panel Molecular Testing Care Pathway and EHR Toolkit comprising an Implementation Roadmap, a Data Pull Guide, and an EHR Clinical Decision Support Tool. These resources reflected the findings from the expert consensus and current literature. The three EHR-based resources are described in Table 3.

Broad Panel Molecular Testing Care Pathway

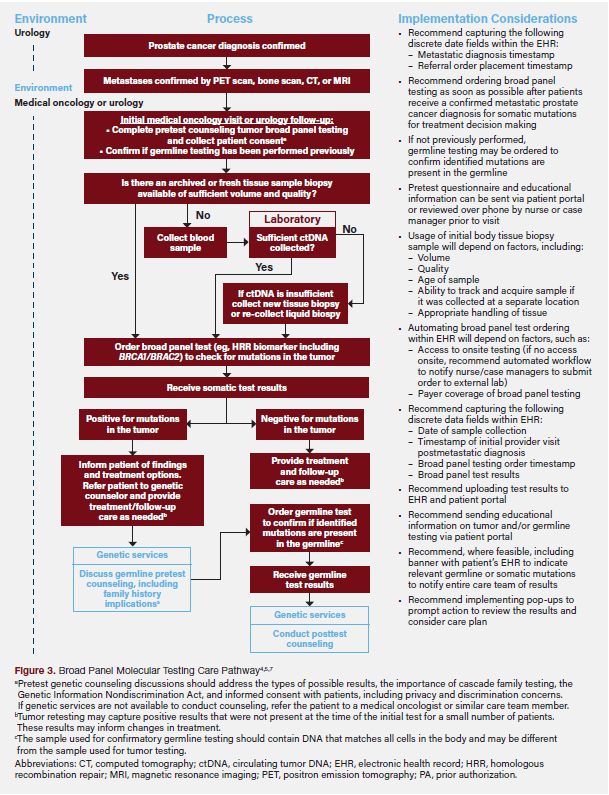

The Broad Panel Molecular Testing Care Pathway4,5,7 for patients with mPC reflects optimal care (Figure 3). It entails three essential components: patient identification (identifying who should be tested), test selection and ordering (determining the appropriate test), and care navigation (guiding patients through care).

Patient Identification

Imaging, such as positron emission tomography, bone scan, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging, is recommended to confirm metastases.21 Imaging is typically ordered by a urologist, but a referral may also be made to oncology. Once the metastatic diagnosis is confirmed, the provider will initially determine whether a patient meets exclusion criteria for testing (ie, presence of any other additional diagnoses affecting the care plan) and obtain patient consent. The provider should also confirm whether the patient has previously received germline testing through medical records or patient consultation, as those results may be relevant to treatment. Regardless of previous germline testing, all patients with mPC should undergo tumor testing unless they meet exclusion criteria.4

Test Selection and Ordering

Providers should select a panel that includes the biomarkers of interest (eg, HRR biomarkers, including BRCA1/BRCA2). For optimal results, a tissue sample with sufficient tumor volume and quality is preferred. When a tissue sample is unavailable or insufficient, a liquid biopsy using plasma separated from whole blood can be used; however, this requires sufficient ctDNA, which can have very low levels in patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) who have initiated androgen deprivation therapy, and ctDNA may not provide the same level of sensitivity in assays.22-24 Insurance coverage and reimbursement for testing should be considered when selecting a panel, and ordering should follow the specific laboratory’s processes.

Care Navigation

Once tumor test results are received and show a positive result for pathogenic somatic mutations, the treating clinician should discuss implications and treatment options. Patients without prior germline testing should be referred to a genetic counselor for further guidance and recommended for confirmatory germline testing to determine the origin of the identified mutation.

If tumor test results are negative for pathogenic somatic mutations, the provider should evaluate whether germline testing is still recommended to confirm the negative result. If the disease progresses or does not respond to the initial treatment, the provider and patient may consider retesting the tumor to identify mutations that have developed since the initial molecular test.

Discussion

Broad Panel Molecular Testing Care Pathway

When we developed the Broad Panel Molecular Testing Care Pathway, flexibility and adaptability were key considerations so that it could accommodate a variety of care environments and limitations, such as time and resource availability. While it prioritized community practices, where testing rates are typically lower than in academic settings, it was designed to accommodate a range of testing practices and align with current standards of care.

To ensure optimal quality and reflect evolving tumor biology, the pathway aligns with best practice considerations to use a recent tissue sample. When conducting a tissue biopsy is not possible or would burden the patient (eg, due to multiple procedures to collect samples), a liquid biopsy is the preferred alternative. With the rapidly evolving landscape of broad panel molecular testing, particularly with NGS technology, the Broad Panel Molecular Testing Care Pathway was designed to remain clinically relevant amid anticipated evolutions in the treatment approval landscape during the next 5 to 10 years.

Certain aspects were intentionally excluded from the pathway due to the inherent variability among health systems, as well as to retain adoptability and longevity. These aspects include pretest counseling by genetic counselors (due to limited availability), specific test ordering procedures (which vary across care settings), and detailed treatment options and recommendations (excluded to increase the longevity of the pathway). Providers should refer to the latest guidelines and consider individual patient considerations to determine the appropriate course of treatment.

Broad Panel Molecular Testing Toolkit

Implementation Roadmap

The expert-informed Implementation Roadmap was designed to improve broad panel molecular testing rates and implement guideline-directed care through three key components: patient identification (identifying who should be tested), test selection (determining which test is appropriate), and care navigation (how to take action upon testing results). Table 4 offers suggestions to create care navigation processes for broad panel molecular testing aligned to the unique needs and available resources of each practice. The roadmap helps practices prepare, implement, sustain, and optimize a molecular testing workflow that will assist in implementing guideline-directed care for broad panel molecular testing.

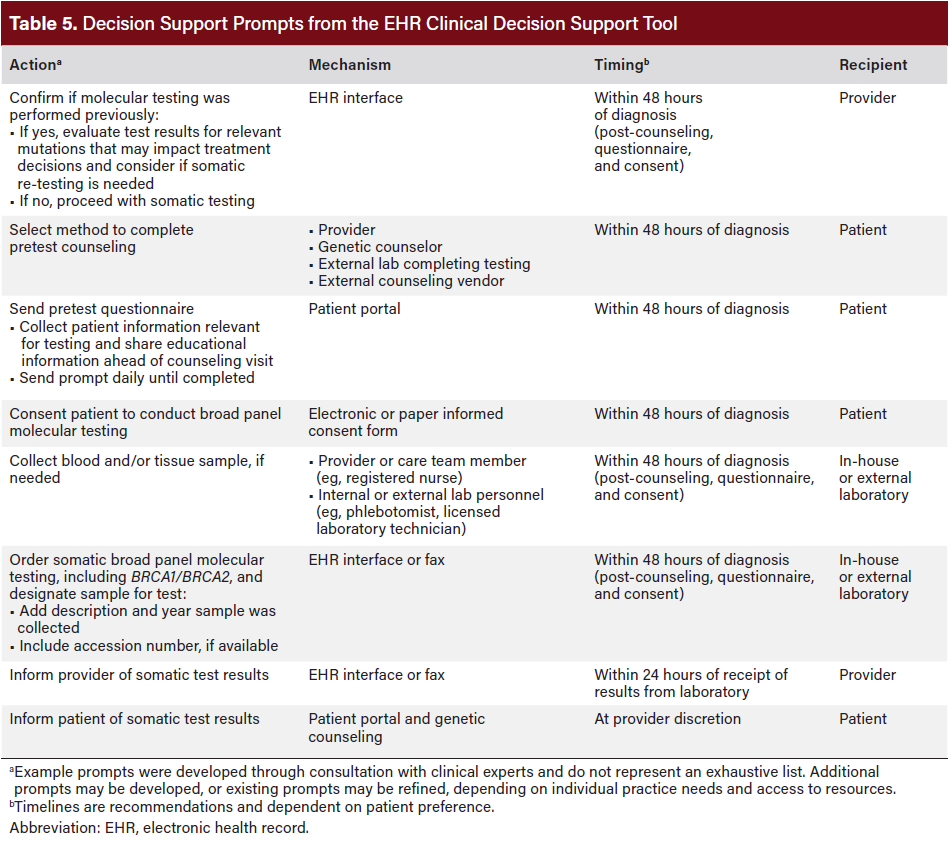

EHR Clinical Decision Support Tool

This tool provides guidance on automating clinical decision-making at the point of patient identification, helping link eligible patients to appropriate testing and care, by leveraging the EHR. The prompts in Table 5 illustrate how this automation can streamline processes that have previously hindered follow-through.

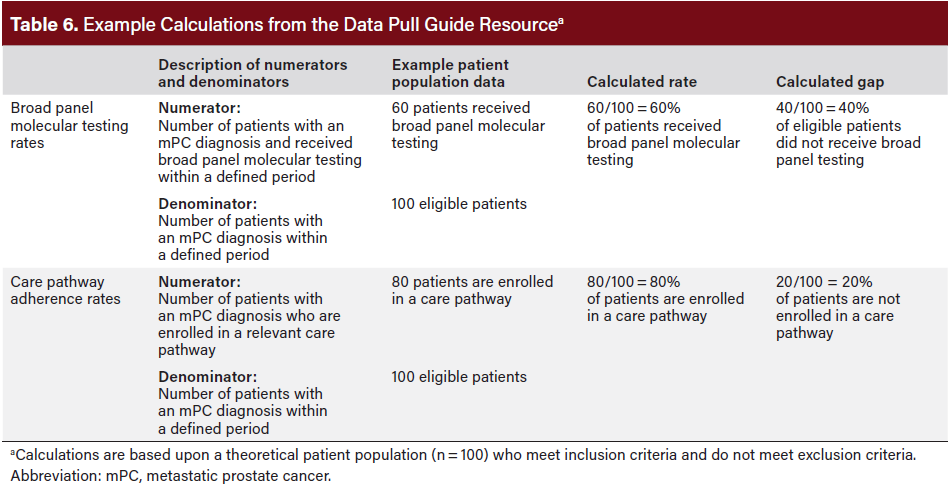

Data Pull Guide

The Data Pull Guide outlines a systematic approach to using the EHR to identify appropriate patients with a recent mPC diagnosis and are eligible for molecular testing but have not received testing. The guide links these eligible patients with appropriate care and monitors testing rates across time (see Table 6 for example testing rate calculations). The calculations reinforce the need for proper coding, which is critical to developing action plans to inform quality improvement initiatives.

Utility and Rationale

The Molecular Testing Care Pathway and EHR Toolkit offer actionable steps and exercises to help practices across care settings optimize care through the EHR. These resources address the high-priority concerns identified in the Delphi study, including patient identification and provider burden. Standardizing care protocols related to broad panel molecular testing may mitigate disparities, address issues related to health equity, and improve access to molecular testing. Similarly, by reducing reliance on individual provider knowledge, the pathway supports standardization of care, paving the way for more equitable access to consistent, evidence-based care.

Limitations

The framework for this initiative heavily builds upon recommendations from an earlier manuscript.10 While designed for broad applicability, the Broad Panel Molecular Testing Care Pathway and EHR Toolkit lack specificity, offering less actionable direction for different EHR systems. In addition, variability in payer policies may further limit patients from receiving guideline-concordant care.

The methodology used has two main limitations: First, the Broad Panel Molecular Testing Care Pathway was designed using the perspective of most participating experts; however, some differing opinions remained. Second, no follow-up roundtable meeting was held to further refine insights from group discussion after the pathway and resources were developed.

Conclusion

Broad panel molecular testing is a powerful tool that can advance patient care if operational barriers can be addressed. To help deliver optimal care for patients with mPC, the Broad Panel Molecular Testing Care Pathway and EHR Toolkit provide guidance to overcome these barriers and support the implementation of actionable solutions. These resources aim to leverage EHR automation to streamline patient identification, simplify the application of clinical practice guidelines, and create cross-disciplinary resources to support clinical decision-making. These tools may help practices increase broad panel molecular testing rates, potentially reduce inequities in mPC care, and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Clinical Pathway Category: Treatment

Developing a standardized care approach that integrates electronic health record (EHR) automation and clinical pathways can improve tumor and germline testing for patients with metastatic prostate cancer (mPC). By aligning with established clinical guidelines and employing evidence-based consensus methods, it contributes to more consistent, equitable oncology care delivery through enhanced clinical decision-making and optimized testing workflows.

Author Information

Authors: Mehmet Asim Bilen, MD1; Aleksandar Zafirovski, MBA2; Robert A. Bailey, MD3; Ibrahim Khilfeh, PharmD3; Urmi Bapat, MD3; Kyra Svoboda, BS4; J. Michael Kramer, MD, MBA5

Affiliations: 1Winship Cancer Institute, Emory University, Atlanta, GA; 2Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL; 3Janssen Scientific Affairs LLC, Titusville, NJ; 4Petauri LLC, New York City, NY; 5Cone Health, Greensboro, NC

Address correspondence to:

Kyra Svoboda

29 Broadway, 26th Floor, New York, NY 10006

Phone: 720.360.6020

Email: kyra.svoboda@petauri.com

Disclosures: M.B. received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Calithera Biosciences Inc, Eisai Co Ltd, EMD Serono Inc, Exelixis Inc, Genomic Health Inc, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc, Nektar Therapeutics, Pfizer Inc, Sanofi, Seagen Inc, and research grants from Advanced Accelerator Applications SA; AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Genentech Inc (a member of the Roche Group), Genome & Company, Incyte Corporation, Merck & Co Inc, Nektar Therapeutics, Seagen Inc, Tricon Pharmaceuticals, Peloton Therapeutics Inc, Pfizer Inc, and Xencor Inc for work unrelated to this manuscript. R.B. owns stock in and is a former employee of Johnson & Johnson. I.K. and U.B. are employees of and own stock in Johnson & Johnson. K.S. is an employee of Petauri LLC.

References

1. McDowell S. Incidence drops for cervical cancer but rises for prostate cancer. American Cancer Society. January 12, 2023. Accessed February 20, 2025. https:// www.cancer.org/research/acs-research-news/facts-and-figures-2023.html

2. Clarke H. Rates of advanced prostate cancer are on the rise, new data show. Urology Times Journal. 2023;51(3). Accessed February 20, 2025. www.urologytimes.com/ view/rates-of-advanced-prostate-cancer-are-on-the-rise-new-data-show

3. Weise N, Shaya J, Javier-Desloges J, et al. Disparities in germline testing among racial minorities with prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2022;25(3):403- 410. doi:10.1038/s41391-021-00469-3

4. Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Prostate Cancer V.1.2025. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2025. Accessed March 4, 2025. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org.

5. Giri VN, Knudsen KE, Kelly WK, et al. Implementation of germline testing for prostate cancer: Philadelphia Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference 2019. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(24):2798-2811. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.00046

6. Eastham JA, Auffenberg GB, Barocas DA, et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO guideline, part I: introduction, risk assessment, staging, and risk-based management. J Urol. 2022;208(1):10-18. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000002757

7. Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, Pancreatic, and Prostate V.3.2025. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2025. Accessed March 13, 2025. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org.

8. Lowrance W, Dreicer R, Jarrard DF, et al. Updates to advanced prostate cancer: AUA/SUO guideline (2023). J Urol. 2023;209(6):1082-1090. doi:10.1097/ JU.0000000000003452

9. Shore N, Raluca Ionescu-Ittu, Yang L, et al. Real-world genetic testing patterns in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Future Oncol. 2021;17(22):2907- 2921. doi:10.1080/14796694.2025.2470616

10. Henderson RJ, Bailey RA, Khilfeh I, et al. Integrating broad panel somatic and germline testing in prostate cancer care. JU Open Plus. 2024;2(12):e00127. doi:10.1200/ OP-25-00186

11. Arvisais-Anhalt S, Ratanawongsa N, Sadasivaiah S. Laboratory results release to patients under the 21st Century Cures Act: the eight stakeholders who should care. Appl Clin Inform. 2023;14(1):45-53. doi:10.1055/a-1990-5157

12. Das S, Salami SS, Spratt DE, et al. Bringing prostate cancer germline genetics into clinical practice. J Urol. 2019;202(2):223-230. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000000137

13. Karantanos T, Corn PG, Thompson TC. Prostate cancer progression after androgen deprivation therapy: mechanisms of castrate resistance and novel therapeutic approaches. Oncogene. 2013;32(49):5501-5511. doi:10.1038/onc.2013.206

14. Hicks JK, Howard R, Reisman P, et al. Integrating somatic and germline next-generation sequencing into routine clinical oncology practice. JCO Precis Oncol. 2021;5:PO.20.00513. doi:10.1200/PO.20.00513

15. Selvarajah S, Schrader KA, Kolinsky MP, et al. Recommendations for the implementation of genetic testing for metastatic prostate cancer patients in Canada. Can Urol Assoc J. 2022;16(10):321-332. doi:10.5489/cuaj.7954

16. Rendon RA, Selvarajah S, Wyatt AW, et al. 2023 Canadian Urological Association guideline: genetic testing in prostate cancer. Can Urol Assoc J. 2023;17(10):314-325. doi:10.5489/cuaj.8588

17. Tukachinsky H, Madison RW, Chung JH, et al. Genomic analysis of circulating tumor DNA in 3,334 patients with advanced prostate cancer identifies targetable BRCA alterations and AR resistance mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(11):3094-3105. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4805

18. CMS finalizes coverage of next generation sequencing tests, ensuring enhanced access for cancer patients. US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. News release. March 16, 2018. Accessed February 20, 2025. www.cms.gov/newsroom/ press-releases/cms-finalizes-coverage-next-generation-sequencing-tests-ensuring-enhanced-access-cancer-patients

19. Payer coverage policies of tumor biomarker and pharmacogenomic testing. American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. March 2023. Accessed February 19, 2025. www.fightcancer.org/sites/default/files/acs_can_payer_coverage_policies_of_ tumor_biomarker_and_pharmacogenomic_testing_-_advi_final.pdf

20. Adler M, Ziglio E, eds. Gazing Into the Oracle: The Delphi Method and Its Application to Social Policy and Public Health. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 1996.

21. Yoon JG, Mohamed I, Smith DA, et al. The modern therapeutic & imaging landscape of metastatic prostate cancer: a primer for radiologists. Abdom Radiol. 2022;47:781- 800. doi:10.1007/s00261-021-03348-6

22. Lin LH, Allison DHR, Feng Y, et al. Comparison of solid tissue sequencing and liquid biopsy accuracy in identification of clinically relevant gene mutations and rearrangements in lung adenocarcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2021;34(12):2168-2174. doi:10.1038/ s41379-021-00880-0

23. Antonarakis ES, Tierno M, Fisher V, et al. Clinical and pathological features associated with circulating tumor DNA content in real-world patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Prostate. 2022;82(7):867-875. doi:10.1038/s41379-021-00880-0

24. Kwan EM, Murtha AJ, Tu W, et al. Impact of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) on circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) detection in de novo metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC). J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(suppl 4):204-204. doi:10.1200/ JCO.2024.42.4_suppl.204