Real-World Outcomes of Next-Generation Sequencing of Progressive Radioactive Iodine Refractory Metastatic Thyroid Cancer and Treatment of These Patients With Redifferentiation Protocol

Abstract

Radioactive iodine (RAI) refractory papillary and follicular thyroid cancer have poor prognoses. These tumors often harbor BRAF V600E and NRAS Q61R mutations, which can be targeted with BRAF and MEK inhibitors to promote redifferentiation. In this study, patients underwent next-generation sequencing (NGS) testing and a 6-week protocol of trametinib and dabrafenib (patients with BRAF V600E mutation) or trametinib alone (patients with NRAS Q61R mutation), followed by dosimetry and therapeutic RAI. Imaging and biochemical analysis were performed at regular intervals. Of 26 patients, 24 showed RAI uptake post-redifferentiation. The correlation between RAI dose and time to response was negligible (0.033), while higher RAI doses showed a moderate negative correlation with progression-free survival (PFS) (−.438), though not statistically significant (P = .278). Telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) positivity significantly reduced PFS by 4.5 months (P = .016). Larger studies are needed to refine patient selection for redifferentiation therapy.

Background

Thyroid cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers in the US, with an estimated 44 020 diagnoses in 2025.1 Thyroid cancer is also highly treatable, with a 98% 5-year-survival rate in the US between 2014 and 2020.1 While differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) is highly treatable, the 5-year-survival rate decreases to 77.6% with single-organ metastasis and 15.3% with multiorgan metastasis.2 Treatment options for these patients also decrease, especially in cases of recurrence or metastasis despite typical first-line treatments. The cornerstone of thyroid cancer treatment is surgical resection followed by selective use of radioactive iodine (RAI) with iodine-131 (I-131) if indicated. Although many patients achieve remission following this treatment, others recur or do not respond well to RAI. These patients are classified as having RAI refractory (RAIR) disease. Patients with RAIR thyroid cancer have poor prognoses and increased risk of recurrent and metastatic disease.3 As the number of patients with thyroid cancer and cases of RAIR disease increase, alternative treatments are being explored.

DTC arises from different types of thyroid cells that are classified by their histopathological differences, whereas papillary (PTC) and follicular thyroid (FTC) comprise approximately 90% of cases. Many cases of DTC involve identifiable driver mutations that are considered central to its pathophysiology.4 These specific molecular abnormalities can be identified with blood-based molecular profiling with circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) or by tissue-based next-generation sequencing (NGS). This understanding has led to significant advances in the development of targeted therapies that help health care providers individualize treatments for patients with advanced-stage thyroid cancer, including those with RAIR disease.

BRAF V600E and NRAS Q61R mutations are commonly found in PTC and FTC; specific kinase inhibitors have been shown to target these mutations and have an antitumor effect.5 These mutations are also common in patients with RAIR disease and are associated with poor prognoses.6 Several studies have been conducted in patients with RAIR disease with BRAF V600E mutations using BRAF inhibitors, such as vemurafenib or dabrafenib, to redifferentiate thyroid cancer cells to become avid to RAI uptake. Using this approach, target lesions have reduced in size after RAI ablation.6

Promising results have also been reported in patients with BRAF V600E or NRAS Q61R mutations using the MEK inhibitor selumetinib. In a study of 20 patients, selumetinib increased RAI uptake in 12 patients, of whom eight were treated effectively with RAI; five patients demonstrated a partial response; and three had stable disease over six months of follow-up. All patients who received RAI following selumetinib therapy had decreased serum thyroglobulin (TG) levels.7

Other mutations that do not have targetable therapies are found frequently in thyroid carcinomas; these must be extensively studied to better understand their impact on RAIR disease. One such example is telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutations, which are associated with poor outcomes in DTC.8

Further study is needed to evaluate this redifferentiation protocol and its outcomes in patients with RAIR disease. Given the promising results and increased prevalence of thyroid cancers over the past four decades, it is important to continue our research on the efficacy of this approach and of molecular analysis to better understand poor prognostic factors, personalize medicine, and increase quality of life and overall survival of patients with thyroid cancer.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective review of electronic medical records at Medstar Washington Cancer Institute using the systems ARIA and MedConnectHealth to identify study participants based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria below. Data tracking, data entry, and storage complied with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations. We identified patients with recurrent or metastatic RAIR PTC or FTC, per American Thyroid Association 2015 guidelines, who had BRAF V600E or NRAS Q61R mutations and underwent the redifferentiation protocol. The mutations were verified via tissue analysis using Caris Life Sciences MI Cancer Seek or ctDNA analysis using Guardant 360 in patients who had recurrent RAIR disease.

The redifferentiation protocol was defined as 6 weeks of therapy with trametinib 2 mg daily and dabrafenib 150 mg twice daily before and during I-131 scan and therapy continued for 3 days after RAI therapy for patients with BRAF V600E mutation, and trametinib 2 mg daily alone for patients with NRAS Q61R mutation. During the 6-week period, patients had serial laboratory tests: complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and tests for thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free thyroxine (T4), serum TG, and TG antibodies. Patients were monitored for toxicities. Low-grade toxicities were managed with conservative treatments, while dose adjustments were made for grades three or four toxicities.

Patient Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients were required to be aged 18 years or older with PTC or FTC. Patients also had to have RAIR disease with either a BRAF V600E mutation or NRAS Q61R mutation. Patients with BRAF V600E mutation underwent the six-week redifferentiation protocol as described below with trametinib and dabrafenib; patients with NRS Q61R mutation underwent the redifferentiation protocol with trametinib alone. Exclusion criteria included patients with thyroid cancer who did not have RAIR disease or a BRAF V600E or NRAS Q16 mutation. Exclusion criteria also included allergies to dabrafenib or trametinib or a score of three or above on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status Scale.

Study Participant Recruitment and Screening

We conducted a retrospective review of patients who were seen in the medical oncology, endocrine, and nuclear medicine clinics, in conjunction with the HIPAA waiver signed by patients. The study participants were screened according to the inclusion criteria.

Nuclear Medicine Protocol

Preparation

Patients were started on a low-iodine diet for at least 14 days before beginning dosimetry scan or therapy. Some patients underwent a four-week withdrawal from levothyroxine, as suggested by the referring endocrinologist. Serum TSH did not exceed 30 mIU/L for RAI administration for scan or therapy. Patients who did not undergo hormone withdrawal received two recombinant TSH injections of 0.9 mg approximately 24 and 48 hours before dosimetry scan and therapy.

Dosimetry

Dosimetry was performed after at least four weeks of initiating the appropriate redifferentiation medication. The dosimetry protocol employed was derived from the Benua-Leeper method,9 which was originally developed at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, with minor modifications to data collection. More details describing this procedure have been published elsewhere.10 The objective of the dosimetry was to calculate the maximum tolerable activity (MTA) such that the radiation absorbed dose to the blood (bone marrow) did not exceed 200 rad (cGy), allowing for the administration of the most effective radioiodine therapy dose within this context.

A prescribed activity of 2 mCi (74 MBq) of 131-I was administered orally for the dosimetry. Anterior and posterior whole-body images, anterior spot images of the neck and chest, and anterior pinhole collimator images of the thyroid bed were obtained. If necessary, single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging was performed. RAI uptake was then measured with an uptake probe in an area 25 cm to 30 cm between the face and neck.

Therapeutic Radioactive Iodine

Therapeutic RAI was administered after redifferentiation agents for at least six weeks total. Oral administration of the prescribed activity was performed with informed consent. Prescribed activity was determined by the nuclear medicine physician in discussion with the referring endocrinologist, based on multiple factors, including MTA by dosimetry, dosimetry scan findings, laboratory values, and clinical aspects of the patient.

Post-therapy scans were performed approximately five to seven days after treatment and included anterior and posterior whole-body and chest imaging. Pinhole images of the neck with and without markers in anterior projections SPECT computed tomography (CT) imaging were performed as necessary.

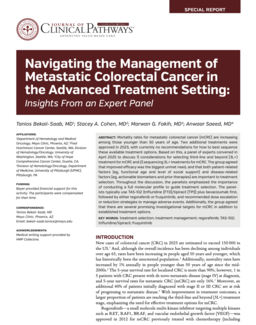

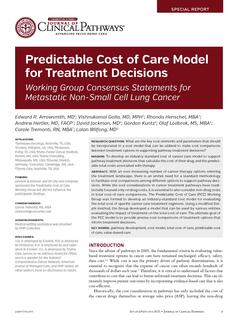

Example Whole-Body RAI Scan

A 75-year-old female patient underwent thyroidectomy with central and right lateral cervical lymph node dissection in 2014. Histopathology demonstrated multifocal PTC, with the largest focus measuring 1.5 cm with positive extrathyroidal extension around the thyroid cartilage, positive lymphovascular central lymph node involvement (11/21), and positive right lateral cervical lymph node involvement (3/14) (staged T4, N1b). The patient had recurrent disease in the neck and underwent modified neck dissection, which confirmed metastatic disease in the right central and right inferior cervical lymph nodes (4/9). Molecular testing via the Caris Life Sciences MI Cancer Seek was positive for BRAF V600E mutation. The patient’s serum TG levels continued to rise despite having undergone a second surgery. Positron emission tomography–CT confirmed involvement of the right jugulodigastric lymph nodes with increasing size and number of bilateral pulmonary nodules.

A whole-body radioiodine scan in light of increasing TG was negative. The patient underwent redifferentiation therapy with dabrafenib and trametinib per standard protocol. Repeat RAI dosimetry scan demonstrated RAI avid bilateral lung metastases and mild uptake within the right jugulodigastric lymph node (Figure 1). The patient underwent dosimetry-guided therapy with 256 mCi of I-131. The post-therapy scan demonstrated significantly avid uptake with bilateral lung metastases (Figure 2).

Follow-Up and Surveillance

Following therapeutic RAI, patients stopped targeted therapies 3 days after administration. Repeat CT scans and blood work with a CBC, CMP, and tests for TSH, TG, and TG antibodies were performed every three months posttreatment to assess for disease recurrence until six months after therapy and every six months thereafter.

Patient Data

We collected relevant patient data, including age, gender, date and staging at diagnosis, pathology and mutation status with molecular markers, detailed history of previous RAI treatments (ie, previous number and dosages of RAI treatments and use of thyroid hormone withdrawal vs thyrotropin alfa), dosimetry scan results, RAI dose given after treatment and dosimetry calculation, post-RAI scan results, response on subsequent surveillance CT scans with target lesions analyzed using RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) criteria, and date of disease progression, if applicable. A statistician analyzed these data to identify any trends, with a progression-free survival (PFS) as the primary end point and response rate comparison between patients with and without TERT mutation as the secondary end point.

Results

Following retrospective analysis, 26 patients who underwent redifferentiation protocol met eligibility criteria. All patients had recurrent metastatic RAIR PTC or FTC with previous RAI cumulative dosage prior to protocol ranging from 83 mCi to 700 mCi. Ages ranged from 29 to 76 years; 17 patients were White, eight were African American, and one was Hispanic. The study patients comprised 15 men and 11 women.

Molecular analysis revealed that 20 patients had BRAF V600E mutation and received dabrafenib and trametinib, five patients had NRAS Q61R mutation and received single-agent trametinib, and one patient, whose mutation status was unknown, received single-agent trametinib. Mutation status was identified via tissue sample with NGS for 20 patients and ctDNA analysis for four patients. One patient’s mutation status could not be identified.

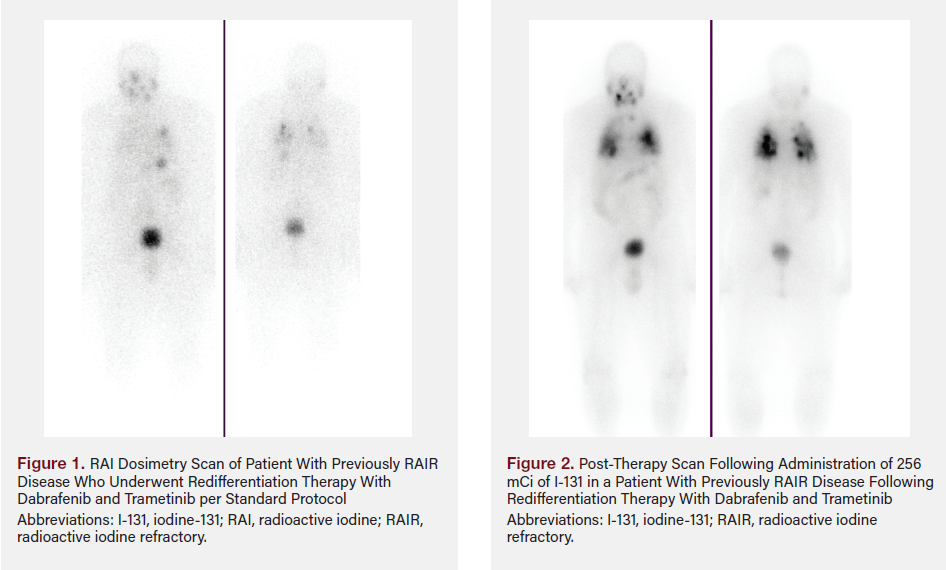

After the redifferentiation protocol, 24 patients had RAI uptake and received I-131 doses of 140 to 357 mCi based on dosimetry scan calculations. Upon analysis of follow-up data, four patients had pending 6-month CT scans (as of the completion of this article), two patients had pending 1-year surveillance CT scans, three patients were lost to follow-up before their 6-month CT scans, and two patients died from comorbid conditions before their 1-year follow-up CT scans. Figure 3 shows survival time in months to first response, response from treatment, and the time of progression of disease, if applicable.

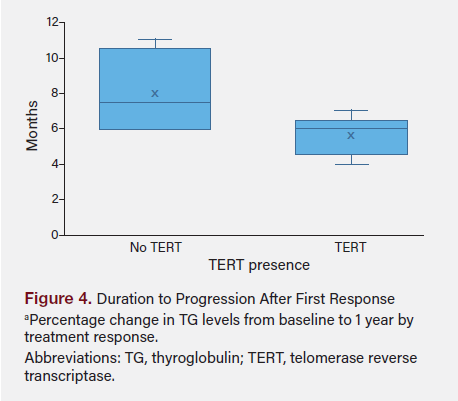

The correlation coefficient between the duration to first response and RAI dosage was very weak (0.033), indicating almost no relationship between the RAI dose and the time to first response. The correlation between the duration to progression after response and RAI dosage was moderate and negative (−0.438), suggesting that higher RAI doses might be linked to a shorter time until disease progression; however, this finding was not statistically significant (P = .278). Figure 4 shows the percentage change in TG levels from baseline (before the redifferentiation protocol) to 1 year by treatment response.

Using the Shapiro-Wilk test, data for duration to progression after response (P = .164) and RAI dosage (P = 0.971) did not significantly deviate from normal distribution. The t test comparing the duration to progression after response between patients with and without TERT mutations yielded a t test statistic of −1.965 with a P value of .090, indicating a trend toward significance but did not meet the conventional threshold of P < .05.

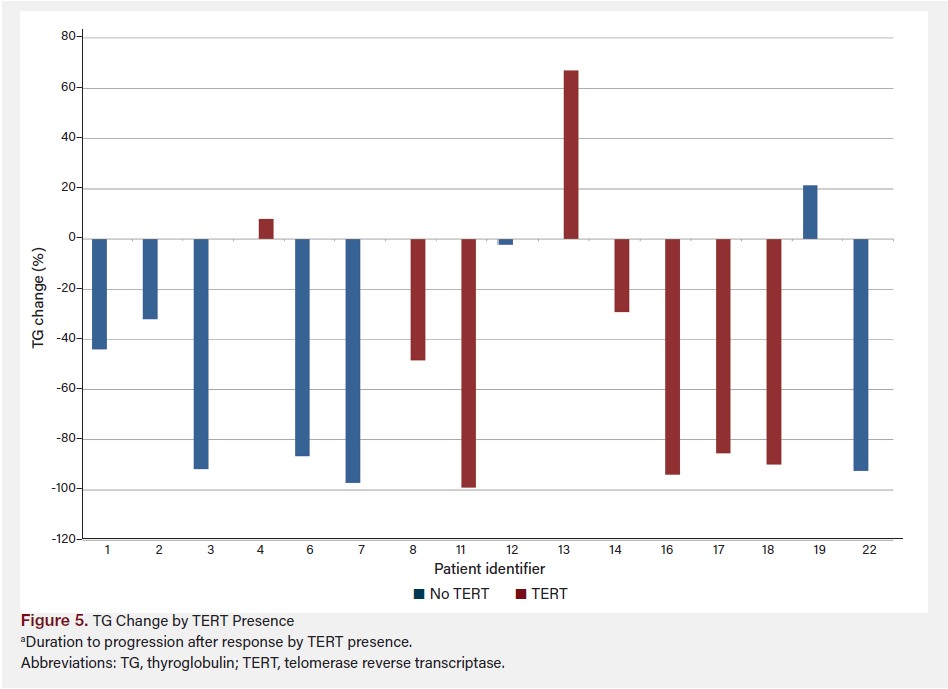

The regression analysis showed that the model had an R-squared value of 0.810, meaning 81% of the variability in progression duration was explained by the model. Significant predictors included the presence of TERT, which was associated with a significant reduction in progression duration by 4.5 months (P = .016), and cancer stage, with stage II and stage IV trending toward significance in reducing progression duration. Figure 5 shows the duration to progression after initial response in relationship to presence of TERT mutation.

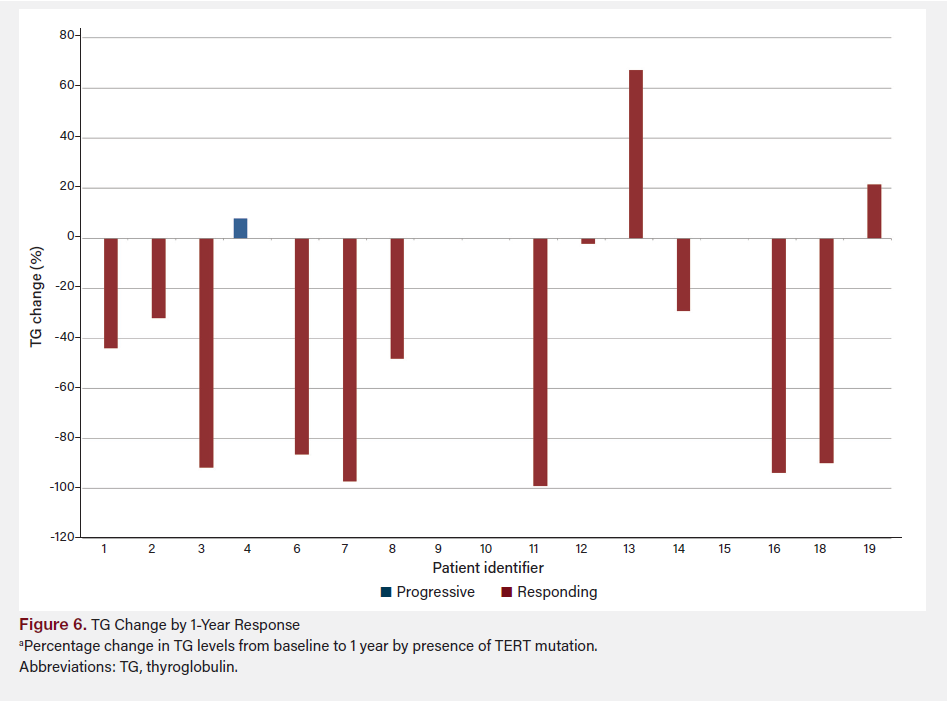

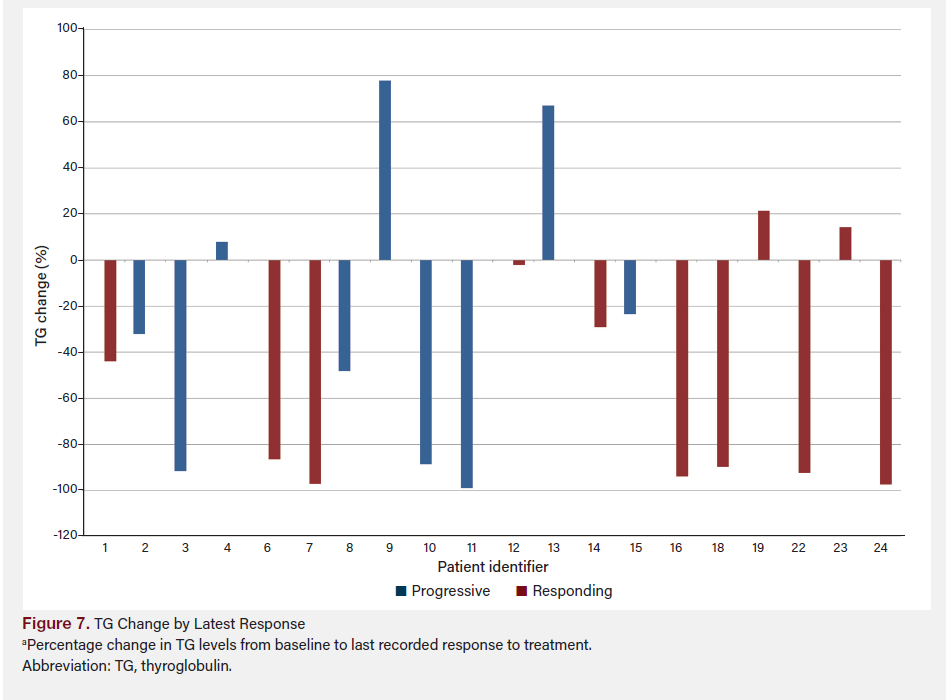

Figure 6 shows TG change by TERT presence from baseline (prior to redifferentiation) to 1 year after treatment, grouped by presence or absence of TERT mutation. Figure 7 shows TG change by TERT and response using the last available TG data for each patient, combining both TERT presence and response to treatment.

The difference in TG percentage change between patients deemed “progressive” and “responding” was not statistically significant (P = .27). However, the mean difference between the two groups was −28.64%, with a mean decrease of 54.22% in the “responding” group vs 25.58% in the “progressive” group. The difference between the group with TERT vs without TERT was not statistically significant (P = .86); a small mean difference of 4.6% was observed between the groups (−38.56% with TERT vs −43.17% without TERT). A post-hoc power analysis was conducted to assess the robustness of our findings. The calculated effect size (Cohen’s d) was −1.256, suggesting a large effect size and substantial difference between the groups with and without TERT mutations. To achieve 90% power (α = .05), the required total sample size is approximately 29 patients. Given that our study included nine patients, 20 additional patients are needed to reach the desired statistical power. The choice of 90% power is conservative, reflecting our intent to minimize the risk of type II errors and ensure that findings are reliable and clinically meaningful. This underscores the importance of expanding the sample size in future studies to validate these preliminary findings and achieve more conclusive results.

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis of patients with recurrent or metastatic RAIR PTC or FTC harboring BRAF V600E or NRAS Q61R mutations, redifferentiation therapy followed by RAI demonstrated a range of clinical outcomes. All 26 patients were determined to have RAIR disease before starting the redifferentiation protocol, and 24 patients (92%) exhibited RAI uptake post-redifferentiation therapy.

Although RAI dosage showed a moderate correlation with time to disease progression after response, this correlation did not reach statistical significance. This suggests that while redifferentiation therapy may enhance RAI uptake in this patient population, the administered dose of RAI post-redifferentiation may not be a strong predictor of durable disease control.

The presence of TERT promoter mutations emerged as a significant factor, associated with a 4.5-month reduction in duration to disease progression, suggesting they may potentially impact the efficacy of redifferentiation therapy. However, the small study sample size limits confidence in this finding, and a larger cohort is required to better delineate the role of TERT mutations in this context.

Our findings align with previous studies indicating that molecular profiling and targeted therapies can influence outcomes in patients with advanced thyroid cancer, particularly those with RAIR disease. This study’s use of BRAF and MEK inhibitors, such as dabrafenib and trametinib, is consistent with other reports that have demonstrated redifferentiation and subsequent RAI responsiveness in a subset of patients with BRAF V600E mutations. Similarly, the use of trametinib in patients with NRAS Q61R mutations also reflects a growing body of evidence supporting its utility in promoting RAI uptake in RAIR thyroid carcinomas.

The variability in response and lack of a significant relationship between RAI dosage and PFS may reflect the heterogeneity of DTC and support the need for a larger cohort and additional research to optimize treatment protocols. Although a moderate negative correlation was observed between RAI dose and duration to progression, it was not statistically significant, raising questions about the potential impact of higher RAI doses on disease progression. This finding contrasts with the anticipated outcome, where higher RAI doses might be expected to prolong disease control.

Several factors may explain the lack of correlation between RAI dose and PFS in this cohort. All patients underwent individualized dosimetry-based treatment with I-131, and redifferentiation was successful in most cases. However, no consistent association was observed between the administered dose based on activity and improved PFS. This may be due to biological factors beyond iodine uptake, such as the rapid efflux of RAI from the tumor cells, variable intracellular retention, or intrinsic tumor resistance mechanisms. Additionally, the presence of co-occurring genetic alterations, such as TERT promoter mutations, may negatively influence the therapeutic effect of redifferentiation. It is also likely that other unidentified molecular alterations contribute to this variability.

Additionally, the lack of a significant difference in PFS between patients with and without TERT mutations, despite the observed trend, underscores the need for larger studies to validate these preliminary observations. The high R-squared value (0.810) in the regression analysis indicates that the model used in this study accounted for a significant portion of the variability in progression duration, yet the small sample size limited the statistical power to detect more subtle effects.

Safety outcomes were not a primary focus of this retrospective study; however, the management of toxicities associated with redifferentiation therapy and subsequent RAI administration appeared consistent with established protocols. The absence of unexpected toxicities suggests that the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib (for BRAF-mutated cases) or trametinib alone (for NRAS-mutated cases) is feasible in this patient population and did not differ from safety outcomes with each treatment alone.

Conclusion

Although redifferentiation therapy followed by RAI shows promise for improving outcomes in patients with RAIR PTC or FTC, particularly those with BRAF V600E or NRAS Q61R mutations, the impact of RAI dosage on disease progression remains unclear. The presence of TERT mutations may further complicate treatment outcomes and significantly reduces the duration to progression, necessitating a more personalized approach to therapy. Future studies with larger cohorts are essential to refine these findings, further explore the role of TERT mutations, and establish more robust biomarkers to guide treatment decisions in this challenging patient population.

Clinical Pathway Categories: Treatment + Outcome Measurements

This study supports the treatment category of clinical pathways by showing that targeted redifferentiation therapy restores RAI sensitivity in most radioactive iodine (RAI)-refractory thyroid cancers, potentially expanding therapeutic options for previously untreatable cases. It also advances outcome measurements by linking molecular markers like TERT to progression-free survival, guiding personalized care and aligning with evidence-based oncology standards.

Author Information

Authors: Jennifer Wheeley, MS, FNP-C1; Nikita Chintapally, MD1,2; Kanchan Kulkarni, MD1; Gabriel Yohe, MS3; Priya Kundra, MD1; Jennifer Rosen, MD1,2; Mohammed Shaikh, MD1; Meeta Sharma, MD1; Jason Wexler, MD1; Kenneth D. Burman, MD1; Leila Shobab, MD1; Irina Veytsman, MD4

Affiliations: 1MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, DC; 2MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC; 3MedStar Health Research Institute, Hyattsville, MD; 4Washington DC Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Washington, DC

Address correspondence to:

Jennifer Wheeley, MS, FNP-C

MedStar Georgetown Cancer Institute at MedStar Washington Hospital Center

110 Irving St NW C2149

Washington, DC 20010

Tel: 202-877-3043

Fax: 202-877-8910

Email: Jennifer.R.Wheeley@medstar.net

Disclosures: The authors disclose no financial or other conflicts of interest.

References

1. Siegel RL, Kratzer TB, Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin. 2025;75(1):10-45. doi:10.3322/caac.21871

2. Wang LY, Palmer FL, Nixon IJ, et al. Multi-organ distant metastases confer worse disease-specific survival in differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2014;24(11):1594- 1599. doi:10.1089/thy.2014.0173

3. Lim H, Devesa SS, Sosa JA, Check D, Kitahara CM. Trends in thyroid cancer incidence and mortality in the United States, 1974-2013. JAMA. 2017;317(13):1338-1348. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.2719

4. Singh A, Ham J, Po JW, Niles N, Roberts T, Lee CS. The genomic landscape of thyroid cancer tumourigenesis and implications for immunotherapy. Cells. 2021; 10(5):1082. doi:10.3390/cells10051082

5. Brose MS, Cabanillas ME, Cohen EEW, et al. Vemurafenib in patients with BRAFV600E-positive metastatic or unresectable papillary thyroid cancer refractory to radioactive iodine: a non-randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(9):1272-1282. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30166-8

6. Subbiah V, Kreitman RJ, Wainberg ZA, et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic BRAF V600-mutant anaplastic thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(1):7-13. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.73.6785

7. Ho AL, Grewal RK, Leboeuf R, et al. Selumetinib-enhanced radioiodine uptake in advanced thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:623-632. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1209288

8. Bournard c, Descotes F, Decaussin-Retrucci M, et al. TERT promoter mutations identify a high-risk group in metastasis-free advanced thyroid carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2019;108:41-49. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2018.12.003

9. Benua RS, Cicale NR, Sonenberg M, Rawson RW. The relation of radioiodine dosimetry to results and complications in the treatment of metastatic thyroid cancer. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1962;87:171-182.

10. Van Nostrand D, Atkins F, Yeganeh F, Acio E, Bursaw R, Wartofsky L. Dosimetrically determined doses of radioiodine for the treatment of metastatic thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2002;12(2):121-134. doi:10.1089/105072502753522356