Percutaneous Imbrication of the Achilles Tendon to Treat a Plantar Central Heel Ulceration: A Novel Indication

This article introduces a minimally invasive technique designed to functionally shorten an over-lengthened or weakened Achilles tendon and correct calcaneal gait, reducing pathologic heel loading without a formal tendon transection. The authors position this protocol as a practical surgical option for medically complex patients who may not tolerate more invasive reconstructive procedures.

Key Takeaways

- Heel ulcers carry an outsized risk of limb loss for patients with diabetes and vasculopathy. Persistent pressure, infection risk, neuropathy, and PAD make these wounds difficult to offload and slow to heal, contributing to proximal amputation and recurrence.

- Calcaneal gait is a key biomechanical driver of plantar heel ulceration and may be iatrogenic after Achilles lengthening. Over-lengthening or weakness of the gastrocnemius-soleus complex increases plantar heel pressure; correcting the underlying mechanics may become necessary.

- Percutaneous Achilles tendon imbrication offers a less invasive surgical path. By shortening the tendon without transection and maintaining correction with nonabsorbable suture (adjusting anchoring strategies when osteomyelitis is a concern), the technique aims to support ulcer healing while enabling earlier, structured return to ambulation in a boot-based protocol.

Heel ulcerations are notably difficult to treat, due to the increased plantar pressure, presence of deep infection, peripheral neuropathy, and peripheral arterial disease in high-risk patients with medical comorbidities.1-3 They result in the highest rate of proximal lower extremity amputation of all foot ulcerations, with 85 percent of heel ulcerations going onto proximal lower extremity amputations.1,4 Heel ulcerations can be the result of multiple etiologies and can be anatomically categorized as plantar and/or posterior. Posterior ulcerations are most commonly decubitus, or pressure induced, in nature5; whereas, plantar heel ulcerations often result from biomechanical abnormalities, including calcaneal gait.6,7 A weakened gastrocnemius-soleus complex or Achilles tendon leads to increased plantar heel pressure and induces calcaneal gait.8,9 Alternatively, calcaneal gait can be iatrogenic due to a surgically over-lengthened Achilles tendon.7,10

Treatment options for heel ulcerations remain limited and associate with severity of the presenting pathology. One can correct the biomechanical etiology via ankle arthrodesis, transection with shortening repair of the Achilles tendon, and/or flexor hallucis longus tendon transfers.6 These are invasive surgeries, and therefore, not ideal treatment options for high-risk patients. The primary aim of this article is to introduce a novel treatment protocol for calcaneal gait resulting from an over-lengthened Achilles tendon or a weakened gastrocnemius-soleus complex. This presentation outlines the surgical technique for functionally shortening the Achilles tendon without creating a transection, which we feel is ideal for high-risk patients with calcaneal gait resulting in heel ulcerations.

Notes on the Surgical Technique

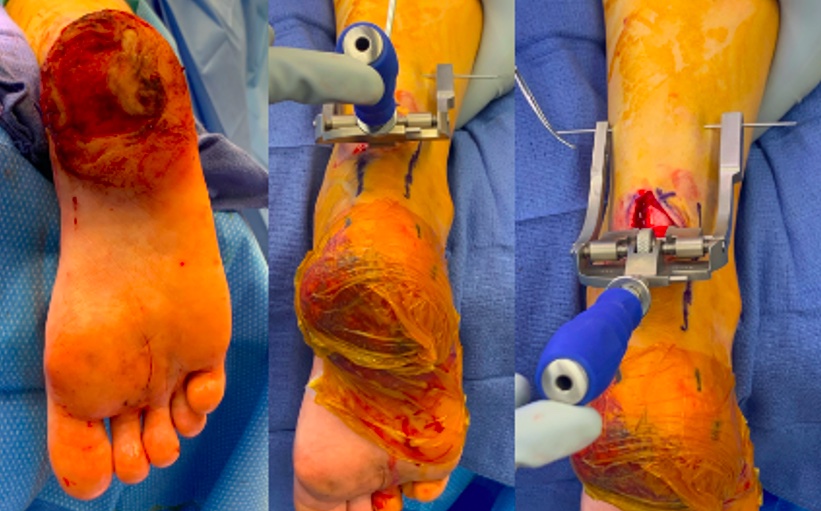

This method of surgical management of calcaneal gait is an imbrication of the Achilles tendon through minimally invasive methods. The authors’ method allows for functional shortening of the Achilles tendon, without transection, appealing for high-risk cases where calcaneal gait resulted in heel ulcerations (Figure 1). Additionally, surgeons strive to maintain correction through the use of non-absorbable suture.

After the patient receives appropriate sedation based on medical risk stratification, positioning is prone with the patient’s feet slightly past the edge of the table to allow for adequate ankle range of motion. Sharp debridement of the heel ulcer takes place in keeping with standard of care with removal of all nonviable soft tissue and bone as indicated. Our team then isolates the heel ulceration from the rest of the sterile field, through use of Ioban (3M). Once applying this protective layer, the surgical team changes their top layer gloves, and applies a new sterile drape. We then turn our attention to the posterior leg for the percutaneous Achilles tendon imbrication. A longitudinal incision at the midpoint between the Achilles myotendinous junction and calcaneal insertion is the next step. The surgeon carries the incision down to the paratenon, and makes a longitudinal incision here with care taken to retain the paratenon tissue for future re-approximation. We insert a percutaneous Achilles repair jig’s (Arthrex) inner arms within the paratenon. Through the outer arms of the percutaneous Achilles repair jig, external to the leg, we then pass nonabsorbable, ultra-high molecular weight suture material through the midsubstance of the proximal Achilles tendon (Figure 2), taking care not to engage too far proximal near the myotendinous junction. We collect the sutures medially and laterally, then passing them out of the incision to their ipsilateral sides, in preparation of either anchoring into the calcaneus with biocomposite anchors (in confirmed absence of osteomyelitis), or directly into the distal Achilles insertion with free needles. The surgeon accomplishes this through two stab incisions over the distal medial and lateral posterior calcaneus. In the case of biocomposite anchor placement, two bone tunnels are made under fluoroscopic guidance. We then insert a beveled tendon passer through the stab incisions (intrasubstance) medially and laterally to allow for protected passage of the proximal sutures distally toward the calcaneus. One must take care at this juncture to avoid the sural nerve. Biocomposite anchors then secure the sutures into the calcaneus under appropriate Achilles tendon tension with plantarflexion of the ankle to 10 degrees.

If concern for calcaneal osteomyelitis exists, the authors advocate for suture passage inferiorly and securing them into the medial and lateral pillars of the intact Achilles insertion. It is the surgeon’s preference as to whether the case warrants a split-thickness skin graft, negative pressure wound dressing, local tissue rearrangement, or allograft/xenograft skin graft substitute application. After irrigating and appropriately closing the incisions, we apply xeroform with gauze, wrapped with cotton undercast padding, followed by a Sir Robert Jones splint in 10 degrees of plantarflexion. The patient is instructed to remain non-weight-bearing for two weeks with a wound assessment in one week. They may then weight-bear as tolerated in a controlled ankle motion (CAM) boot with heel lifts, followed by two more weeks of weight-bearing as tolerated in a controlled ankle motion boot without heel lifts (Figure 3).

Discussing The Challenge and Solutions

Calcaneal gait is often the result of an over-lengthened or weakened posterior muscle group, which increases heel pressure, and predisposes to soft tissue breakdown.8,11,12 There is a 4.3 percent rate of calcaneal gait after Achilles tendon lengthening.8 Further, the rate of calcaneal gait was higher in patients who underwent Achilles tendon lengthening compared to those treated with total contact casting for forefoot ulcerations, 13.3 percent compared to 7.1 percent respectively.13 Other authors have demonstrated an ulceration rate up to 14 percent after Achilles lengthening, characterizing this procedure as less benign than once thought.14

Heel ulcerations, although common, have limited viable treatment options. Nonoperative treatments include offloading, restricted weight bearing, and strength training as needed via physical therapy. Temporizing surgical measures include debridement, external fixation, surgical offloading, and graft applications, yet these do not address the underlying biomechanical etiology.15 Introduction of the vertical contour calcanectomy provides reasonable option in the case of calcaneal osteomyelitis, allowing for large calcaneal resection producing a large soft tissue envelope for primary closure. This may prove beneficial in low-demand community ambulators, as opposed to highly functional individuals, due to a requirement for an adjunctive Achilles tenotomy.16-18 Tenectomy in isolation can result in calcaneal gait pathology, too.16-18 Some authors advocate for more definitive means of surgically correcting the over-lengthened posterior myotendinous complex through ankle arthrodesis, primary Achilles tendon repair, or flexor hallucis longus tendon transfer.19,20 Ankle arthrodesis negates the pull of Achilles tendon by fusing the primary joint the tendon impacts; however, the procedure is relatively invasive and is often not a viable option for patients with which osseous healing could be an issue.21,22 Alternately, transection of the Achilles tendon with resection, shortening, and primary repair, or adjunctive flexor hallucis longus tendon transfer, has been described to re-establish posterior muscle group strength.23 These methods often require large incisions and adequate biological healing of the transected tendon.20

Calcaneal gait can result from a number of etiologies including trauma, neurologic disorders, and musculoskeletal deformity.24 Traumatic rupture and surgical Achilles tendon lengthening both result in elongation of the Achilles tendon, possibly leading to the development of calcaneal gait. In studies reviewing patients casted after ankle open reduction with internal fixation, patients developed a statically significant resistance to passive elastic stiffness with significant stiffness being reached at 7-9 days of immobilization.25,26 Physically decreasing sarcomere length aids in contracture development. This, coupled with non-enzymatic glycation of the Achilles tendon, enables stiffness of the Achilles tendon.27,28

Our focus on this procedure as a novel surgical indication is its use in high-risk patients with either an iatrogenically over-lengthened Achilles tendon or calcaneal gait from any of the aforementioned influences. Our approach uses a percutaneous Achilles tendon imbrication and shortening technique which allows for incorporation of nonabsorbable sutures with the goal of developing an appropriate degree of contracture to maintain correction. Soft tissue imbrication is a commonly utilized technique to effectively tighten soft tissue at a site of tissue laxity. By suturing adjacent tissues with overlapping edges, the surgeon shortens the targeted segment and subsequent scarring at the operative site allows for maintenance of correction. Imbrication of the medial patellofemoral retinaculum is commonly utilized for surgical management of chronic patellofemoral instability.29 In foot and ankle surgery, primary repair and imbrication of the anterior talofibular ligament through the arthroscopic Broström technique has produced excellent long-term results in management of chronic lateral ankle instability with no statistically significant difference when comparing open versus percutaneous imbrication.30-32 Our utilization of imbrication of the soft tissues of the Achilles tendon for functional shortening offers a similar effect as other techniques by recreating anatomic tendon tightness to treat calcaneal gait. Salsich and colleagues, using a dynamometer, were able to show a decrease in maximum passive dorsiflexion in patients with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy compared to age matched controls (10.8 +/- 5.2 vs. 17.6 +/- 4) and the authors appreciated that shortened musculature contributed to this effect.33 Additionally, with medical comorbidities such as diabetes, there is a known degree of propensity for contracture which creates and additive benefit for considering this technique.

There are several limitations to our technique. Most importantly, there is a need for published long term outcomes assessing for recurrence of ulceration and complications. Additionally, there would be benefit from further studies comparing other historic surgical techniques for managing calcaneal gait to the described novel technique. Finally, the described technique has limited indications and is only for use in high-risk patients exhibiting calcaneal gait and an associated ulcer/preulcerative lesion. Despite these limitations, we believe our technique for the treatment of calcaneal gait can assist patients in treating the underlying biomechanical etiology of a plantar central heel ulceration. We further hope that this preliminary report will allow for prospective cohort studies and randomized controlled trials focused on managing this pathology.

This novel surgical indication for percutaneous Achilles imbrication in the setting of calcaneal gait allows for functional shortening the Achilles tendon and has been shown, in our experience, to be a useful adjunct to healing calcaneal ulceration. The authors believe that this procedure should be added to the armamentarium as a reasonable option for patients with significant medical comorbidities, with incorporation of the minimally invasive technique and early return to ambulation.

Dr. Wynes is an Assistant Professor and Fellowship Program Director in the Department of Orthopaedics at University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore.

Dr. Dubois is a limb preservation and deformity correction fellow in the Department of Orthopaedics at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore.

Dr. McKeown is a resident physician in the Department of Plastic Surgery at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, DC.

Dr. Cates is a fellowship-trained foot and ankle surgeon with the Hand & Microsurgery Medical Group in San Francisco.

Dr. Farahani is a resident physician in the Department of Plastic Surgery at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, DC.

Acknowledgments. This study was supported by the Department of Orthopaedics, University of Maryland School of Medicine. Jacob Wynes is the guarantor of the content of this manuscript. Nicole K. Cates, DPM, AACFAS; Korey S. Dubois, DPM, AACFAS; Kelly McKeon, DPM; Jacob Wynes, DPM, MS, FACFAS: have no financial disclosures, commercial associations, or any other conditions posing a conflict of interest to report.

Declarations

Funding. No funding was received for this project.

Competing interests. Jacob Wynes, DPM, MS, FACFAS; Korey S. Dubois, DPM, AACFAS; Kelly McKeon, DPM; Nicole K. Cates, DPM, AACFAS report they have no relevant disclosures pertaining to this manuscript. Jacob Wynes, DPM, MS, FACFAS reports he is on the speaker’s bureau of Smith & Nephew for medical education, and a consultant for Orthofix for medical education.

Ethics approval and Consent to participate. Since the study was a surgical technique case, and no patient’s information was used in the study, there was no need to obtain informed consent.

Consent for publication. Not applicable. No patient’s information was used in the study.

Data availability. We confirm that we have given due consideration to the protection of intellectual property associated with this work and that there are no impediments to publication, including the timing of publication, with respect to intellectual property. In so doing we confirm that we have followed the regulations of our institutions concerning intellectual property.

Materials availability. The materials used in this study are discussed within the paper.

Code availability. Not applicable.

References

1. Younes NA, Albsoul AM, Awad H. Diabetic heel ulcers: a major risk factor for lower extremity amputation. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004;50(6):50-60.

2. VanGilder C, Lachenbruch C, Algrim-Boyle C, Meyer S. The International Pressure Ulcer Prevalence™ Survey: 2006–2015: a 10-year pressure injury prevalence and demographic trend analysis by care setting. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2017;44:20-28.

3. Nowakowska M, Zghebi SS, Ashcroft DM, et al. The comorbidity burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus: patterns, clusters and predictions from a large English primary care cohort. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):—. doi:10.1186/s12916-020-1492-5

4. Pecoraro RE, Reiber GE, Burgess EM. Pathways to diabetic limb amputation: basis for prevention. Diabetes Care. 1990;13(5):513-521.

5. Fowler E, Scott-Williams S, McGuire JB. Practice recommendations for preventing heel pressure ulcers. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2008;54(10):42-57.

6. Sabapathy SR, Periasamy M. Healing ulcers and preventing their recurrences in the diabetic foot. Indian J Plast Surg. 2016;49(3):302-313.

7. Ong CF, Geijtenbeek T, Hicks JL, Delp SL. Predicting gait adaptations due to ankle plantarflexor muscle weakness and contracture using physics-based musculoskeletal simulations. PLoS Comput Biol. 2019;15(10):e1006993. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006993

8. Dallimore SM, Kaminski MR. Tendon lengthening and fascia release for healing and preventing diabetic foot ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Res. 2015;8:33. doi:10.1186/s13047-015-0085-6

9. Ramanujam CL, Zgonis T. Surgical correction of the Achilles tendon for diabetic foot ulcerations and Charcot neuroarthropathy. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2017;34(2):275-280.

10. Chen L, Greisberg J. Achilles lengthening procedures. Foot Ankle Clin. 2009;14(4):627-637.

11. Kim JY, Hwang S, Lee Y. Selective plantar fascia release for nonhealing diabetic plantar ulcerations. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(14):1297-1302.

12. Nishimoto GS, Attinger CE, Cooper PS. Lengthening the Achilles tendon for the treatment of diabetic plantar forefoot ulceration. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83(3):707-726.

13. Allam AM. Impact of Achilles tendon lengthening on the diabetic plantar forefoot ulceration. Egypt J Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;30:43-48.

14. Holstein P, Lohmann M, Bitsch M, Jørgensen B. Achilles tendon lengthening, the panacea for plantar forefoot ulceration? Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2004;20(1):—. doi:10.1002/dmrr.452

15. Khoo R, Jansen S. Slow to heel: a literature review on the management of diabetic calcaneal ulceration. Int Wound J. 2018;15(2):205-211.

16. Cates NK, Wang K, Stowers JM, et al. The vertical contour calcanectomy: an alternative approach to surgical heel ulcers: a case series. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2019;58(6):1067-1071.

17. Elmarsafi T, Pierre AJ, Wang K, et al. The vertical contour calcanectomy: an alternative surgical technique to the conventional partial calcanectomy. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2019;58(2):381-386.

18. Oliver NG, Steinberg JS, Powers K, et al. Lower extremity function following partial calcanectomy in high-risk limb salvage patients. J Diabetes Res. 2015;2015:—. doi:10.1002/dmrr.452

19. Bevilacqua NJ. Treatment of the neglected Achilles tendon rupture. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2012;29(2):291-299.

20. Boc SF, Norem ND. Ankle arthrodesis. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2012;29(1):103-113.

21. Thevendran G, Shah K, Pinney SJ, Younger AS. Perceived risk factors for nonunion following foot and ankle arthrodesis. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2017;25(1):—.

22. Wang Y, Li Z, Wong DW, Zhang M. Effects of ankle arthrodesis on biomechanical performance of the entire foot. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0134348.

23. Ozer H, Ergisi Y, Harput G, et al. Short-term results of flexor hallucis longus transfer in delayed and neglected Achilles tendon repair. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2018;57(5):1042-1047.

24. Sobel E, Glockenberg A. Calcaneal gait: etiology and clinical presentation. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1999;89(1):39-49.

25. Chesworth BM, Vandervoort AA. Comparison of passive stiffness variables and range of motion in uninvolved and involved ankle joints of patients following ankle fractures. Phys Ther. 1995;75(4):253-261.

26. Nightingale EJ, Moseley AM, Herbert RD. Passive dorsiflexion flexibility after cast immobilization for ankle fracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;456:65-69.

27. Tabary JC, Tabary C, Tardieu C, et al. Physiological and structural changes in the cat’s soleus muscle due to immobilization at different lengths by plaster casts. J Physiol. 1972;244(1):231-244.

28. Grant WP, Sullivan R, Sonenshine DE, et al. Electron microscopic investigation of the effects of diabetes mellitus on the Achilles tendon. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1997;36(4):272-278.

29. Duchman KR, Bollier MJ. The role of medial patellofemoral ligament repair and imbrication. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2017;46(2):87-91.

30. Karlsson J, Bergsten T, Lansinger O, Peterson L. Reconstruction of the lateral ligaments of the ankle for chronic lateral instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(4):581-588.

31. Gould N, Seligson D, Gassman J. Early and late repair of lateral ligament of the ankle. Foot Ankle. 1980;1(2):84-89.

32. Rigby RB, Cottom JM. A comparison of the “all-inside” arthroscopic Broström procedure with traditional open modified Broström-Gould technique: a review of 62 patients. Foot Ankle Surg. 2019;25(1):31-36.

33. Salsich GB, Mueller MJ, Sahrmann SA. Passive ankle stiffness in subjects with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy versus an age-matched comparison group. Phys Ther. 2000;80(4):352-362.

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Podiatry Today or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.