Basics of Patient Specific Instrumentation in Total Ankle Replacement

Precise implant alignment remains a cornerstone of successful total ankle replacement, driving both longevity and functional outcomes. Patient-specific instrumentation has emerged as a key enabling technology, offering surgeons a CT-based, preoperative roadmap designed to enhance accuracy and efficiency. This article examines the evolution, current evidence, and future direction of PSI in total ankle replacement.

Key Takeaways

- PSI improves alignment reliability and operative efficiency—but not superiority over traditional guides.

Current evidence demonstrates that patient-specific instrumentation achieves high accuracy and precision in total ankle replacement, with meaningful reductions in operating room and fluoroscopy time, though overall alignment outcomes remain comparable to conventional instrumentation. - Surgeon oversight is critical to PSI success, particularly in complex or varus deformities.

- CT-based plans should not be accepted without review; surgeon-driven plan modification—especially regarding component positioning, tibial rotation, and medial malleolar thickness—is essential to mitigate complications and optimize outcomes.

- PSI remains the dominant enabling technology in total ankle replacement, but competition is emerging.

While PSI currently leads adoption in TAR, navigation and robotic-assisted technologies are entering the space, suggesting that alignment strategies will continue to evolve as data, workflows, and cost models mature.

History and Current State of the Art

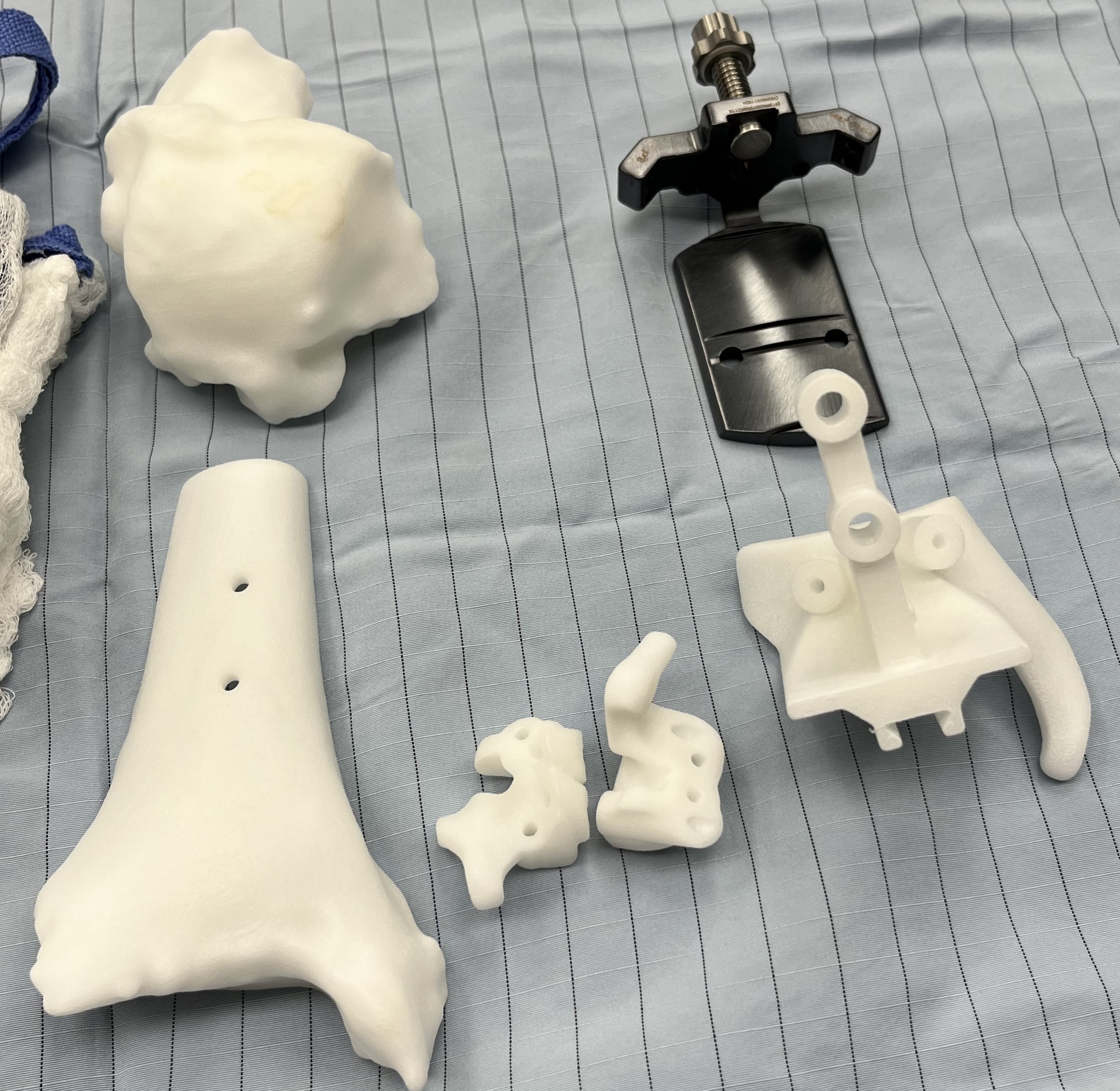

Patient specific instrumentation (PSI) in joint replacement is an enabling technology that surgeons can utilize to attain implant alignment. Studies have long shown that alignment plays a critical role in the success and longevity of total ankle replacement.1-7 Traditional alignment guides are standard instruments that used intraoperatively to align the implant to the extremity. Surgeons achieve this using various outrigger devices or external jigs that secure the foot and ankle with pins; they may use an anterior or lateral approach and rely on either extramedullary or intramedullary anatomic landmarks. PSI uses custom-made, 3D-printed, single-use cut guides (Figure 1). These are based on computed tomography (CT) scans for all current total ankle systems. The guides are intended to interact with the patient’s anatomy, and provide a surface match to the corresponding anatomy, thereby allowing performance of a previously planned “virtual alignment” on the patient (Figure 2). The goals of PSI include improved accuracy, precision, efficiency, and value over traditional alignment techniques.8

Patient specific instrumentation is one aspect of a broader area of “enabling technology,” a category that includes PSI, but also computer navigation and robotic-assisted surgery. PSI in total knee replacement was established in the early 2000s with a report in 2006 discussing the proof of concept in cadavers and plastic knees.9 However, enabling technology overall is expanding and changing. According to the Orthopaedic Industry Report in 2024, enabling technology in orthopedics represented a $1.3 billion market share, and this is expected to increase to $1.8 billion by 2027.10

In 2023, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) reported that although most total knee arthroplasties still used traditional instrumentation, 17.5% employed enabling technology—a proportion that continues to rise.11 The majority of total knee arthroplasty performed with enabling technology utilizes robotic assisted surgery (81%), with only 7% using PSI cutting guides.12 This points to the evolving nature of enabling technology in orthopedics. The Australian Orthopaedic Association’s National Joint Replacement Registry annual report demonstrates how technology continues to change and adapt based on developments.13 In 2003, performance of almost all total knee arthroplasty was with traditional instrumentation. This time frame saw the introduction of computer navigation, which increased until 2017 when it reached just above 30% of total knees. The year 2009 marked the introduction of PSI to the market, which increased to nearly 10% around 2016, and has stayed relatively stable since then. However, robotically assisted surgery emerged in 2016 and dramatically increased in usage to about 30% in 2022, while computer-assisted surgery declined in use during the same period, and now represents less than 25% of total knees. By 2022, less than 40% of total knee arthroplasty reported in the Australian joint registry took place with traditional instrumentation.13 This changing landscape demonstrates the nature of technology and how the definition of “state-of-the-art” will inevitably change with new developments. A recent opinion stated that overall orthopedic PSI “varies greatly between procedures. Exactness is enhanced in the spine, in osteotomies around the knee and in bone-tumor surgery. In the shoulder, their contribution is seen only in complex cases. Data are sparse for hip replacement, and controversial for knee replacement.” No opinion was rendered in foot and ankle.14

Patient specific instrumentation in total ankle replacement (TAR) was introduced in America in 201215 and has seen significant increase since in adoption. In a 2020 study, authors reported placement of 21,222 implants from a single company in the US and Canada from 2012-2019.16 A registry study from the UK looking at early experience with the same implant found that 99 of the 503 (19.7%) implants placed used the PSI system.17 Most recently, a 2025 study reported submission of over 65,000 scans for this same implant system.18 While all these studies refer to the Prophecy system (Stryker), we have since noticed that several other companies have developed and released their own PSI technology and protocols. Smith + Nephew Ankle PSI can be used for Cadence and Salto Talaris implants (Smith + Nephew), Zimmer Biomet/Paragon28 uses the Maven PSI for Apex 3D implants (Paragon28), Enovis uses a specific PSI protocol for the STAR implant (Enovis), Restor3d uses their Axiom PSR technology for the Kinos Axiom ankle (Restor3d), Exactech uses 3D Systems Active Intelligence for the Vantage ankle (Exactech) and ConMed uses OrthoPlanify for their Quantum ankle (ConMed).

Process for Patient Specific Instrumentation in Total Ankle Replacement

The process for obtaining and using PSI for TAR is largely the same, regardless of the specific company and system in question. CT scans remain the basis for all PSI for TAR. The specific company will have a protocol for the scan, and one can send this protocol to the radiology department performing the CT. This will specify position of the foot, slice thickness, and all anatomic landmarks necessary for inclusion. These goals are likely achievable with a non-weight-bearing scan but investigation of weight-bearing scans suggest this may prove helpful with positioning and deformity assessment.19 At minimum, the scan should place the foot in a neutral position, include the entire foot, and at least 10 cm above the ankle joint. The scan should also include the knee to assess mechanical axis, and some companies will recommend the entire tibia. Although neutral position is important for the scan, weight-bearing plain film radiographs may be an adjunctive tool for the engineers to get accurate positioning. Once the scan is complete, one can upload the images to the company for processing.

After uploading, the company engineers will create a plan and send it back for approval from the operating provider. This may take several days to several weeks depending on the company and workflow, and different seasons with high demand may take longer. It is critical for the surgeon to critically assess the plan sent from the company engineers. Several papers have been critical of the “blind trust” that surgeons may place in the provided plans.20-22 Modification of these plans can include many variables such as: size (tibia and talus metallic components), position (coronal and sagittal angulation, translation in 6 degrees of freedom), and change to the specific implant (low profile to medullary stemmed, for example).

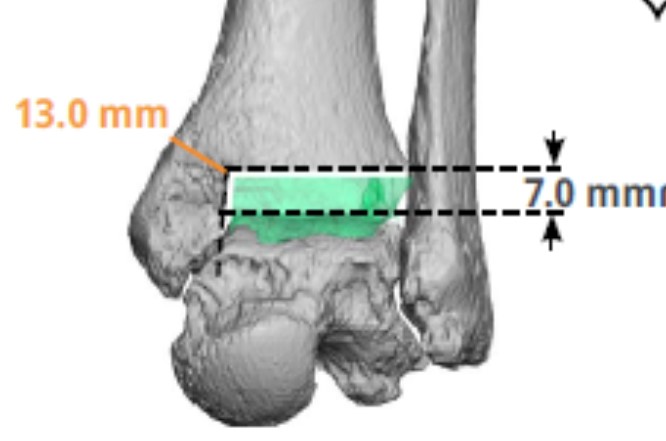

The long axis of the tibia usually aligns the implant to the mechanical axis in the frontal and sagittal planes in these plans, which also determine and illustrate the tibial rotation. One particularly important aspect to evaluate is the medial malleolar thickness, available on the engineer-provided report. The literature indicates that this thickness is a predictor of medial malleolar pain and stress fracture with several papers recommending reinforcement with thickness less than 9.5-10.3 mm (Figure 3).23-25 Surgeons may decide to reinforce this area with prophylactic pinning or increase this thickness by moving the tibial component laterally and/or distally.

We recently published surgeon rejection rates for the PSI plan that they receive, and found that the initial engineer-provided plan was rejected more often in complicated and revision cases, as well as in more recent years, later in the study.18 This indicated that with comfort and familiarity with the technology, the surgeon can make more critical assessment of the plan. However, the engineer-provided plan was initially approved in 91.6% of standard, uncomplicated or non-revision cases, representing high confidence these simpler cases. After a plan rejection, the average time to get the revised plan was around 30 hours.18 This process continues until the surgeon approves the plan.

Once approved, 3D printing of the PSI guides takes place. This will include the guides that will surface match to the patient at the tibia or talus, and some are coupled. This will also include models of the patient’s tibia and talus to trial the fit and position to facilitate surgical positioning on the patient. Some companies or implants may also have accessory guides for further assistance in alignment. Once printed, the guides ship to the representative who gets them to the hospital or surgery center. These guides are nonsterile, single use, and disposable. They require sterilization at the hospital, so timing with the company, representative, a hospital sterile processing department is important.

Details on the Perioperative PSI Process

After sterilization, the surgical team opens guides and models using continued sterile technique, along with the rest of the instruments for the surgery. The surgeon proceeds with the standard surgical approach, exposing the ankle joint. The guides are made to surface match the bony architecture, so there must be meticulous removal of any soft tissue from the surface match area and may require debridement with cautery. The preoperative approved plan can help confirm this match area as can the 3D-printed bone model. The plan will also point out necessity of any loose body or hardware removal, or if indeed, the surgeon should leave these in place for the surface match.

Different companies will use different areas for the surface match, and we recently evaluated accuracy or guides that surface match to the distal tibial osteophytes compared to the anterior surface of the medial malleolus and anterior tibia proximal to the joint line.26 Sixteen patients using a medial malleolar surface match were matched based on coronal plane alignment 1:2 with 32 patients using distal tibial osteophyte surface match as a control group. The medial malleolar group deviated from expected in the coronal plane by 1.6° ± 1.3° compared to the distal tibial group deviating 1.1° ± 0.6° from expected (P = .04). This corresponded to 68.8% in the medial malleolar group being within 2° of expected compared to 93.4% in the distal tibial group. While one can consider both groups accurate, the distal tibial osteophyte group was moreso, and surgeons need to take into consideration how and where to obtain the surface match.26

Even with this surface match, multiple checks must take place to compare the alignment obtained compared to the alignment planned. This includes comparing to the alignment plan, fluoroscopic checks of alignment, use of X-ray guides, and even laser alignment. While the degree of accuracy is high, one cannot blindly trust the initial surface match.

Is PSI a Good Option for TAR?

In the literature, stated goals of navigation in TAR include: accuracy and precision; efficiency; and value.8 Multiple papers examined accuracy based on the plan or compared to standard instrumentation. A composite of 6 papers including 225 patients27-32 found that coronal plane alignment had no statistically significant difference in predicted versus actual alignment, and only one paper29 had a difference in the sagittal plane. We looked at 97 patients to describe accuracy or PSI for TAR and found the average coronal plane alignment was 0.7° ± 1.2° different than predicted and was 0.7° ± 1.5° in the sagittal plane.33 We then broke down patients into varus (>5° varus), valgus (>5° valgus) and neutral (<5° coronal plane alignment) and found that there was a statistically significant loss of predictability for patients in the varus (1.1° ± 1.3°) group compared to the valgus group (0.3° ± 1.1°), P = .02.33 Comparing PSI to traditional alignment, a composite of 6 papers including 362 patients (20, 34-38) revealed that only one study38 found a difference in coronal plane alignment, and a different study for the sagittal plane.35 Accuracy and precision are clearly demonstrated in PSI, although there has not been any clear improvement observed over traditional alignment.

Efficiency as measured by operating room (OR) time and fluoroscopy time favors PSI. Five studies including 291 patients that looked at OR time using PSI or traditional alignment found the average OR time using PSI was 143.6 minutes compared to 151.5 minutes with traditional alignment, with only one study37 showing a statistically significant increase in time with PSI.20,34,35,37,38 Two studies also compared fluoroscopic time and found a reduction in fluoroscopic time with PSI.20,38 A systematic review in 2021 of 9 studies concluded that PSI is equal for alignment and accuracy, less accurate for implant size, but improves OR time and fluoroscopy usage.39

Value can be measured both in terms of cost and functional outcomes. Two studies using a Time Driven Activity Based Cost (TDABC) analysis found that even with a reduction in OR time, PSI was more expensive by slightly more than $800, while a more traditional accounting method found there was a nearly $8000 cost savings with PSI.34,35 However, many hospitals will cap the cost of the implants regardless of use of PSI, and some surgeons will opt for a CT scan even without PSI guidance. Also, there is the contention that cost of time in the OR is not the only time involved in PSI, as the surgeon needs to spend time reviewing and revising the plan. Although that time is not quantifiable, it may be time well spent.18,22 Overall, cost is difficult to quantify, but it is logically more expensive when using PSI. Similarly, several studies have looked at functional outcomes when using PSI compared to traditional alignment. There are some areas of improvement in specific functional outcomes, but no clear advantage overall in patient-reported outcomes.38,40,41

What is the Future of PSI?

PSI for TAR is currently the most common enabling technology in use. It has significantly increased in use over time, and this trend seems to be continuing. However, it is no longer the only enabling technology. A computed navigation system for the Exactech Vantage ankle called GPS Ankle technology (Exactech) was given FDA 510(k) clearance in December 2023.42 Announcements of the first surgeries took place in March 2025. While this is a new technology in total ankle replacement, this is established, higher volume use in total knee replacement. But even this technology has lost market share in the total knee market to robotic assisted surgery, as discussed from the Australian joint registry.13 While PSI in TAR is currently a useful enabling technology for alignment and offers improved intraoperative efficiency, like any technology, there are likely to be changes in the future. Navigation is a newer, yet unproved technology in the total ankle space, but further developments are all but inevitable in the future.

Drs. DeVries and Scharer are board-certified in rearfoot and ankle reconstructive surgery by the American Board of Foot and Ankle Surgery, are fellowship-trained, and partners at Orthopedic and Sports Medicine at BayCare Clinic in Manitowoc, WI.

References

- Espinosa N, Walti M, Favre P, Snedeker JG. Milsalignment of total ankle components can induce high joint contact pressures. J Bone Joint Surg. 2010;92-A(5):1179-1187.

- Fukuda T, Haddad SL, Ren Y, Zhang LQ. Impact of talar component rotation on contact pressure after total ankle arthroplasty: a cadaveric study. Foot Ankle Int. 2010:31(5):404-411.

- Tochigi Y, Rudert MJ, Brown TD, McIff TE, Saltzman CL. The effect of accuracy of implantation on range of movement of the Scandanavian Total Ankle Replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:736-740.

- Barg A, Elsner A, Anderson AE, Hintermann B. The effect of three-component total ankle replacement malalignment on clinical outcome: pain relief and functional outcome in 317 consecutive patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:1969-1978.

- Queen RM, Adams SB Jr, Viens NA, et al. Differences in outcomes following total ankle replacement in patients with neutral alignment compared with tibiotalar joint malalignment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1927-1934.

- Le V, Escudero M, Symes M, et al. Impact of sagittal talar inclination on total ankle replacement failure. Foot Ankle Int. 2019;40:900-904.

- De Keijzer DR, Joling BSH, Sierevelt IN, Hoornenborg D, Kerkoffs GMMJ, Haverkamp D. Influence of preoperative tibiotalar alignment in the coronal plane on the survival of total ankle replacement: a systematic review. Foot Ankle Int. 2020;41:160-169.

- Reb CW, Berlet GC. Experience with navigation in total ankle arthroplasty. Is it worth the cost? Foot Ankle Clin N Am. 2017;22:455-463.

- Hafez MA, Chelule KL, Seedom BB, Sherman KP. Computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty using patient-specific templating. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;444:184-192.

- Evers M. The Orthopaedic Industry Annual Report ® Published by Orthoworld®. Chagrin, OH, USA: OrthoWorld, Inc.; 2024. Accessed December 19, 2025. Available at: https://www.orthoworld.com/the-orthopaedic-industry-annual-report.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American joint replacement registry, Annual Report 2023; p. 81. Accessed December 19, 2025. Available at https://connect.registryapps.net/hubfs /PDFs20and20PPTs/AJRR20202320Annual20Report.pdf?hsCtaTracking=cc920 3b1-b118-49b8-b606-3a1a9530a657C189d3ddc-5ecd-4902-a9ba-3e68b2303c7a.

- Orthopedic Network News by Curvo: 2023 Hip and Knee Implant Review; 2023;34(3):19-20. Accessed December 19, 2025. Available at www.onn.curvolabs.com.

- Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry, Hip, knee & shoulder arthroplasty Annual report 2022:282. Accessed December 19, 2025. Available at: https:// aoanjrr.sahmri.com/en-US/annual-reports-2022.

- Gauci, MO. Patient-specific guides in orthopedic surgery. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2022:108(1S):103154.

- Maudlin RG, Bradfish C. 3D orthopaedic pre-operative surgical planning for total ankle replacement. In: Roukis TS, Hyer CF, Berlet GC, Bibbo C, Penner MJ, eds. Primary and Revision Total Ankle Replacement: Evidence-Based Surgical Management, 2nd ed, 93-106, Switzerland; Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2021.

- Penner MJ, Berlet GC, Calvo R, et al. The demographics of total ankle replacement in the USA: a study of 21,222 cases undergoing preoperative CT scan-based planning. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2473011420S00381.

- Townshend DN, Bing AJF, Clough TM, Sharpe IT, Goldberg A. Early experience and patient-reported outcomes of 503 INFINITY total ankle arthroplasties. Bone Joint J. 2021;103-B(7):1270-1276.

- DeVries JG, Scharer BM. Rejection rate, modifications, and turnaround time for patient specific instrumentiation for patient specfici instrumentation plans in total ankle replacement. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2025;64(5):516-520.

- Thompson MJ, Consul D, Ubmel BD, Berlet GC. Accuracy of weight bearing CT scans for patient-specific instrumentation in total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2021;6(4):1-6.

- Saito GH, Sanders AE, O’Malley MJ, Deland JT, Ellis SJ, Demetracopoulus CA. Accuracy of patient specific instrumentation in total ankle arthroplasty: a comparative study. Foot Ankle Surg. 2019;25:383-389.

- Roukis TS, Hyer CF. Patient-specific instrumentation in total ankle replacement. Podiatry Today. 2022;35(2):22–25. Available at, https://www. hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/podiatry/case-study/patient-specific-instru mentation-total-ankle-replacement.

- Roukis TS. Patient-specific instrumentation for total ankle replacement: the Emperor’s new clothes redux. FASTRAC. 2022;2:100153. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.fastrc.2022.100153.

- Cottom JM, Badell JS, Dunn KW, Ekladios J, Iatrogenic medial malleolar fracture and stress fracture considerations in total ankle joint replacement: A multicenter retroscpective study. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2025;64(5):619-623.

- Palma J, Shaffrey I, Cororaton A, Kim J, Ellis SJ, Demetracopoulos C. Postoperative medial malleolar fractures in total ankle replacement are associated with medial malleolar width and coronal alignment. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2023: 2473011423S00059.

- Lundeen GA, Dunaway LJ. Etiology and treatment of delayed-onset medial malleolar pain following total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37(8):822-828.

- DeVries JG, Regal A, Tuifua TS, and Scharer BM. Distal tibial osteophytes are more accurate than medial malleolar anatomy when using patient specific instrumentation in total ankle replacement. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2025;64(5):546-551.

- Hsu AR, Davis WH, Cohen BE, Jones CP, Ellington JK, Anderson RB. Radiographic outcomes of preoperative CT scan-derived patient-specific total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36(10):1163-1169.

- Togher CJ, Golding SL, Ferrise TD, Butterfield J, Reeves CL, Shane AM. Effects of patient-specific instrumentation and ancillary surgery performed in conjunction with total ankle implant arthroplasty: postoperative radiographic findings. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2022;61(4):739-747.

- Biela G, Piraino J, Roukis TS. Analysis of 50 consecutive total ankle replacements undergoing preoperative computerized tomography scan-based, engineer-provided planning from a single noninventor, nonconsultant surgeon. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2022:;S1067-2516(22)00208-3. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2022.06.013

- Daigre J, Berlet G, VanDyke B, Peterson KS, Santrock R. Accuracy and reproducibility using patient-specific instrumentation in total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Int. 2017:38(4):412-418

- Umble BD, Hockman T, Myers D, Sharpe D, Berlet GC. Accuracy of ct-derived patient-specific instrumentation for total ankle arthroplasty. The impact of the severity of pre-operative varus ankle deformity. Foot Ankle Spec. 2022:Jan 7;19386400211068262. doi: 10.1177/19386400211068262.

- Thompson MJ, Consul D, Umbel BD, Berlet GC. Accuracy of weightbearing CT scans for patient-specific instrumentation in total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2021:6(4):1-6.

- Regal A, Tuifua TS, Scharer BM, DeVries JG. Effect of preoperative coronal plane alignment on actual versus predicted alignment using patient specific instrumentation in total ankle replacement. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2024;63(6):724-730.

- Hamid KS, Matson AP, Nwachukwu BU, Scott DJ, Mather RC, DeOrio JK. Determining the cost-savings threshold and alignment accuracy of patient specific instrumentation in total ankle replacements. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;38(1):49-57.

- Savage-Elliott I, Wu VJ, Wu I, Heffernan JT, Rodriguez R. Comparison of time and cost savings using different cost methodologies for patient-specific instrumentation vs standard referencing in total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2019;4(4):1-6.

- Escudero MI, Le V, Bemenderfer TB, et al. Total ankle arthroplasty radiographic alignment comparison between patient-specific instrumentation and standard instrumentation. Foot Ankle Int. 2021;42(7):851-858.

- Heisler L, Vach W, Katz G, Egelhof T, Knupp M. Patient-specific instrumentation vs standard referencing in total ankle arthroplasty: a comparison of the radiologic outcome. Foot Ankle Int. 2022;43(6):741-749.

- Giardini P, Benedetto PD, Mercurio D, et al. Infinity ankle arthroplasty with traditional instrumentation and PSI prophecy system: preliminary results. Acta Biomed. 2020;91:S. 14:e2020021, doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i14-S.10989.

- Wang Q, Zhang N, Guo W, Wang W, Zhang Q. Patient-specific instrumentation (PS) in total ankle arthroplasty: a systematic review. Int Orthop. 2021;45:2445-2452.

- Albagi A, Ge SM, Park P, et al. Total ankle arthroplasty results using fixed bearing CT-guided patient specific implants in posttraumatic versus nontraumatic arthritis. Foot Ankle Surg. 2022;28(2):222-228.

- Yau J, Emmerson B, Kakwani R, Murty AN, Townsend DN. Patient-reported outcomes in total ankle arthroplasty: patient specific versus standard instrumentation. Foot Ankle Spec. 2024;17(1 Suppl):30S-37S.

- Ali S, US Food and Drug Administration. K232521 ExactechGPS® total ankle application, 21 CFR 882.4560, stereotaxic instrument. Aug 18, 2023. Available at: Wang Q, Zhang N, Guo W, Wang W, Zhang Q. Patient-specific instrumentation (PS) in total ankle arthroplasty: a systematic review. Int Orthop. 2021;45:2445-2452. Accessed December 19, 2025.

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Podiatry Today or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.