Nonsurgical Healing of a Fifth Metatarsal Fracture: A 16-Month Case Report

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Podiatry Today or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Metatarsal fractures are a common forefoot injury encountered in the emergency department or urgent care setting, accounting for 3–7% of all fractures.1 The fifth metatarsal is the most frequently fractured, representing up to 68% of all metatarsal fractures.2 Fractures are generally classified by location: base, shaft (diaphysis), neck, or head. While fifth metatarsal base fractures have received significant attention due to higher rates of nonunion or malunion from vascular compromise, management of shaft fractures is less standardized.

Fractures of the fifth metatarsal diaphysis, commonly referred to as “dancer’s fractures” or spiral fractures, frequently occur in dancers and typically result from a roll over the foot while weight-bearing on the metatarsophalangeal joints (demi-pointe position).3 However, they also occur in other active individuals. Management strategies range from conservative care to surgical intervention. Historically, recommendations included open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) for fractures with displacement greater than 3 mm or angulation exceeding 10 degrees4; however, contemporary literature increasingly supports nonsurgical management for appropriately selected patients.

This case study presents a 16-month follow-up of a patient with an isolated fifth metatarsal shaft fracture, highlighting radiographic progression and clinical healing under conservative management. It is particularly relevant for clinicians in urgent care or emergency department settings, who may encounter these fractures frequently but may be less familiar with current evidence-based treatment protocols.

Details on the Case Presentation

A 30-year-old healthy male presented with acute right foot pain after kicking a kickball. He reported immediate pain, swelling, and an audible “pop,” with difficulty ambulating and no paresthesia. His health history was overall unremarkable and did not impact the case.

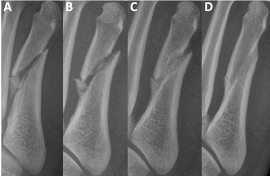

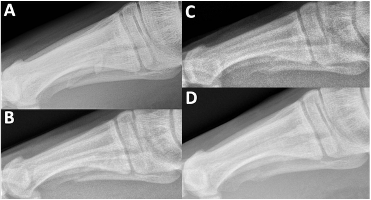

On examination, there was focal tenderness over the dorsal lateral forefoot without gross deformity, open wounds, or sensory deficits. Vascular status was grossly intact. Three views of non-weight-bearing radiographs revealed a mildly comminuted mid-diaphyseal fifth metatarsal fracture with a small angulated butterfly fragment (Figures 1A, 2A, and 3A). On the oblique view there was approximate 3.59mm of gapping noted with 3 distinct fracture fragments. Some shortening of distal metatarsal was apparent as well. The patient was placed in a controlled ankle motion (CAM) boot, provided with crutches, and instructed to remain non-weight-bearing.

At three days post injury, neurovascular status remained intact. There was edema, ecchymosis, and localized tenderness still present. We discussed the treatment plan and natural history of fifth metatarsal fractures with the patient, emphasizing that surgical intervention was not required based on the workup and current findings. We advised him to continue non-weight-bearing for 2 more weeks, then transition to protected weight-bearing in the CAM boot for 4 weeks.

One month after the initial injury, swelling and ecchymosis had resolved, and pain was improved. He was able to weight-bear in the CAM boot without difficulty. Follow-up weight-bearing radiographs showed stable alignment with no interval displacement (Figures 1B, 2B, and 3B). We advised him to advance to weight-bearing as tolerated in supportive shoe gear after 2 additional weeks.

At the 4 month mark, weight-bearing radiographs demonstrated osseous bridging across the fracture site (Figures 1C, 2C, and 3C). By 11 months, the patient was pain-free and had returned to full activity. Non-weight-bearing radiographs confirmed complete fracture union with preserved joint spaces and no deformity (Figures 1D, 2D, and 3D). At 16 months, he remained asymptomatic with normal activities of daily living.

Discussion

Isolated fractures of the fifth metatarsal shaft represent about 25% of all fifth metatarsal injuries.1 They typically occur from ground reaction forces applied to the metatarsal head and neck when the foot is plantarflexed, producing a triplanar rotational load. This results in the well-described spiral or oblique fracture pattern.5 Herterich and colleagues identified 3 distinct regions for diaphyseal fractures and noted that the distal lateral meta-diaphyseal region is most vulnerable due to decreased cortical thickness and the bone’s lateral curvature.1 Our patient’s radiographs were consistent with this classic pattern.

In our case, the patient progressed well with conservative treatment. He reported symptom improvement by 1 month, radiographic union by 4 months (~17 weeks), and complete cortical remodeling by 11 months, with no complications. This recovery compares favorably to the 21.9 weeks reported by Jones and team in patients managed nonoperatively. While ORIF did have an association with faster return to activity (13 weeks in athletes), the operative group was significantly younger, which may have influenced results.6

Immobilization strategies have also been studied. Morgan and colleagues found that patients treated in a rigid-soled shoe achieved pain-free walking earlier than those in a CAM boot (4.6 vs. 8.4 weeks).2 Schwagten and coworkers, however, found no difference between immobilization methods in dancer’s fractures.7 Our patient had no issues with boot immobilization, though the literature suggests a rigid shoe may offer comparable outcomes at lower cost and with better patient comfort.2

Although some advocate surgery for faster recovery or in cases with displacement, our experience and support from the literature suggests that conservative care remains a safe and effective option in healthy patients that can and do adhere to treatment recommendations. The risk of delayed or nonunion appears low when patients follow immobilization guidance and are free of comorbidities such as smoking. This case reinforces that conservative management can achieve excellent outcomes, and that surgery is not always necessary for isolated fifth metatarsal shaft fractures.

Conclusion and Clinical Pearls

This case demonstrates that isolated fifth metatarsal shaft fractures in healthy, active adults can potentially be managed conservatively with excellent outcomes. Key points for urgent care and ED clinicians, or for any provider conducting the initial workup in the acute setting:

• Initial management: non-weight-bearing for up to 1 month in a stiff-soled shoe or CAM boot.

• Gradual progression: advance weight-bearing as tolerated and based on radiographic progress

• Expected healing: radiographic union by ~4 months with full return to activity.

• Fracture characteristics: mild displacement or angulation does not necessarily require surgery.

While not new information, this case further supports existing research that conservative management is a safe and effective alternative to surgery for this fracture type. Importantly, it also underscores that emergency and urgent care providers, who often first encounter these injuries, can confidently initiate conservative treatment protocols, leading to reliable healing and excellent long-term outcomes.

Dr. Frey is a resident at Denver Health and Hospital Authority in Denver, CO.

Dr. Gorski is an attending podiatrist at Denver Health and Hospital Authority in Denver, CO.

References

1. Herterich V. Fracture pattern analysis of fractures to the diaphysis of the fifth metatarsal. Foot Ankle Surg. 2024;30(1):10-15. doi:10.1016/j.fas.2023.11.001.

2. Morgan C, Abbasian A. Management of spiral diaphyseal fractures of the fifth metatarsal: a case series and review of literature. Foot (Edinb). 2020 Jun;43:101654. doi:10.1016/j.foot.2019.101654.

3. Smidt KP, Massey P. 5th Metatarsal Fracture [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544369/

4. Shereff MJ. Fractures of the forefoot. Instr Course Lect. 1990;39:133–140.

5. Thompson P, Patel V, Fallat LM, Jarski R. Surgical management of fifth metatarsal diaphyseal fractures: A retrospective outcomes study. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2017 May-Jun;56(3):463-467. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2017.01.009.

6. Jones MD, et al. Conservative versus surgical management of distal fifth metatarsal diaphyseal fractures in athletes and nonathletes. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2023;113(1):20-195. doi:10.7547/20-195.

7. Schwagten K, Gill J, Thorisdottir V. Epidemiology of dancer’s fracture. Foot Ankle Surg. 2021 Aug;27(6):677-680. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2020.09.001.