Transforming Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Procedures With 3D Intracardiac Echocardiography:

Expert Insights From Andrew M Goldsweig, MD, MS

Expert Insights From Andrew M Goldsweig, MD, MS

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of EP Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

EP LAB DIGEST. 2025;26(1):Online Only.

Interview by Jodie Elrod

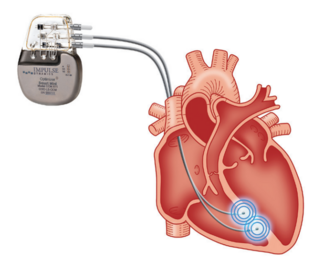

As left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) rapidly expands in both volume and technical sophistication, a major shift is underway in how electrophysiologists and structural heart teams guide these procedures. Increasingly, 3-dimensional (3D) intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) is emerging as a compelling alternative—and in some centers, a preferred option—to traditional transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). In this interview, EP Lab Digest speaks with Dr. Andrew M. Goldsweig, coauthor of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) Position Statement on ICE to Guide Structural Heart Disease Interventions,1 to explore the real-world advantages of 3D ICE, what an optimal ICE-guided LAAO workflow looks like, why clinicians are adopting this imaging strategy, and how ICE may reshape structural and electrophysiology (EP) practice in the years ahead.

For LAAO cases specifically, when you look at current 3D ICE catheters versus classic 3D TEE, what do you see as the practical advantages—sedation strategy, patient selection, imaging windows, and procedure time—that would make a center seriously consider an ‘ICE-first’ approach rather than TEE by default?

ICE guidance for LAAO offers clinical, economic, and patient preference advantages over TEE guidance.

Clinically, ICE guidance allows avoidance of the risks of TEE (esophageal injury, dental injury) and general anesthesia (aspiration, hypotension/hypoperfusion). This advantage is especially pronounced in patients with underlying frailty, tenuous airways, pulmonary disease, esophageal disease, and challenging esophageal and tracheal anatomy for TEE and endotracheal intubation.

Economically, ICE guidance avoids the expenses of anesthesiology and TEE providers. Furthermore, ICE guidance has been shown to reduce LAAO procedure time by an average of 27 minutes, decrease room turnover time, lower Post-Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) utilization, shorten length of stay, and increase same-day discharge rates—each contributing to reduced overall expenses. As LAAO expands to lower-risk populations—an acceleration that is especially anticipated following the upcoming presentation of the CHAMPION-AF trial results—procedural throughput will become increasingly important. Hospitals, and likely ambulatory procedure centers, will need to perform a high volume of LAAO procedures both expediently and safely. In this setting, 3D ICE guidance will be essential for increasing procedure throughput to meet growing demand.

Lastly, patients vastly prefer conscious sedation over general anesthesia and are eager to avoid the invasiveness associated with TEE.

Based on the workflow outlined in the SCAI Position Statement, can you describe an ideal step-by-step approach to ICE-guided LAAO—from venous access and home view, through transseptal puncture, to final device assessment—and highlight where 3D ICE meaningfully changes practice compared with 2D ICE or traditional TEE-guided procedures?

ICE guidance is an appropriate imaging strategy for LAAO as supported by the SCAI/HRS LAAO Guidelines.2

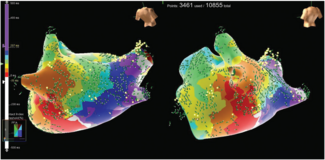

The 3D ICE-guided LAAO procedure begins with nurse-administered conscious sedation, typically with midazolam and fentanyl. Two vascular access sites 1-cm apart are obtained in the right femoral vein, typically a superior 9 to 10 French (F) ICE site and an inferior LAAO device delivery site. The ICE catheter is advanced to the right atrium (RA) home view to document any baseline pericardial effusion. The catheter is rotated clockwise to the RA septal view. (If the LAA is not adequately visualized to rule out thrombus, and if the patient has not been on anticoagulation prior to the procedure, the ICE catheter may be advanced into the pulmonary artery to visualize the apex of the LAA clearly to rule out thrombus.) From the RA septal view, 3D ICE allows biplane imaging to guide transseptal puncture with both anterior-posterior and superior-inferior views. After transseptal puncture, the device delivery sheath is advanced into the LA to dilate the septum and then retracted into the RA. The ICE catheter is advanced along the transseptal wire into the LA using both fluoroscopy and ICE guidance. The ICE catheter is placed in the mid LA with slight retroflexion, parallel to the LAA ostium. Except for mild adjustments to optimize imaging, the ICE catheter can remain in this position until after LAAO device deployment. Three-dimensional ICE allows measurement of the LAA in the aortic, mitral, and pulmonic valve views through digital rotation of the imaging plane, unlike 2D ICE, which requires multiple catheter manipulations and cannot always obtain every view. The LAAO device is deployed under biplane ICE guidance. The LAAO device is then assessed and measured in the aortic, mitral, and pulmonic valve views, just as the LAA was assessed prior to deployment. When appropriate, the LAAO device is released and the catheter is withdrawn. The ICE catheter is withdrawn to the RA home view to assess for pericardial effusion and then removed. The access sites can be closed using closure devices or, simply and inexpensively, with a single figure-of-8 suture placed around both sites.

In your view, what are the main reasons a lab should move toward ICE-guided LAAO—and what are the biggest real-world barriers (eg, cost, training, workflow, reimbursement) that still hold clinicians back?

The clinical, economic, and patient preference reasons described above are the main reasons to move toward a 3D ICE-first strategy for LAAO. The biggest real-world barrier is physician training: many electrophysiologists and interventional cardiologists are comfortable using 2D ICE to guide transseptal puncture but are not comfortable or facile using 3D ICE to guide LAAO. Costs are lower with ICE guidance than with TEE guidance, as described above. In addition, the cost of 3D ICE catheters is decreasing as multiple companies compete in the field. Third-party companies are also now purchasing and sterilizing 3D ICE catheters for resale at significantly lower prices than new catheters. The peri-procedural workflow for 3D ICE-guided LAAO is similar to that of other common procedures such as ablations or cardiac catheterizations. By using 3D ICE, hospitals can rely on this standard workflow rather than the general anesthesia and TEE workflow, which is not standard in most cardiac procedural areas. At present, ICE is reimbursed only through the add-on CPT code +93662. However, as ICE guidance expands to more procedures, the American Medical Association’s CPT Panel is expected to revisit this reimbursement paradigm, and professional societies (Heart Rhythm Society, SCAI, American College of Cardiology) are advocating for enhanced reimbursement for ICE guidance in structural heart procedures.

As ICE becomes increasingly central to contemporary EP and transcatheter workflows, how should programs structure training for both interventionalists and imaging physicians so that ICE is incorporated as a routine component of procedural practice rather than a modality reserved only for select or infrequent cases?

ICE training must be included in EP and interventional cardiology training programs. One of the best resources for ICE training is the ICE vendors themselves. They offer expert trainers, realistic simulators for various procedures, animal and cadaver lab experiences, and proctorship during initial procedures. As part of the ICE learning process, trainees should begin by performing the ICE imaging portion of procedures, focusing on learning the imaging while a colleague performs the LAAO device manipulation. After gaining confidence with performing the ICE imaging and LAAO components separately, operators will be ready to combine these procedures and perform them simultaneously.

One of the most important elements of ICE training is the incorporation of standardized views as described in detail in the SCAI statement on ICE guidance.1 Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) uses standard views: parasternal long axis (PLAX), parasternal short axis (PSAX), apical 4 chamber (A4C), apical 3 chamber (A3C), apical 5 chamber (A5C), subcostal, etc. TEE uses standard views: mid-esophageal 4-chamber, bicaval, transgastric, etc. Similarly, ICE operators must now communicate using standardized, named views: home, septal, LV from RV, LAA from PA, mid-LA views of the LAA (aortic, mitral, and pulmonic), among others. New operators must learn how to obtain and interpret each of these ICE views as described and depicted in the SCAI statement.1

Looking ahead, how do you see 3D ICE changing LAAO and broader structural and EP practice? Do you expect it to replace TEE in certain workflows?

The combination of rising procedure volumes and stagnant or declining global medical reimbursement will drive rapid growth in the use of ICE guidance. ICE will enable operators to perform more procedures, shorten lengths of stay, and reduce costs. ICE will increasingly replace TEE for guiding LAAO and septal interventions (patent foramen ovale/atrial septal defect), and many transcatheter tricuspid edge-to-edge repair and even mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair procedures will use ICE instead of TEE. In the future, as reimbursement paradigms evolve, stand-alone ICE will also likely become an excellent option in place of TEE for patients with contraindications to TEE who require evaluation for valvular disease, endocarditis, or LAA thrombus prior to cardioversion.

References

1. Eleid MF, Chung CJ, Daniels MJ, et al. SCAI Position Statement on Intracardiac Echocardiography to Guide Structural Heart Disease Interventions. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2025;4(12):103946. doi:10.1016/j.jscai.2025.103946

2. Goldsweig AM, Glikson M, Joza J, et al. 2025 SCAI/HRS Clinical Practice Guidelines on Transcatheter Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2025;4(9):103783. doi:10.1016/j.jscai.2025.103783