Breaking the Silos: Inside the EP-Heart Failure Collaborative Model Delivering Integrated Care: Interview With Daniel A Steinhaus, MD, and Timothy J Fendler, MD, MSc

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of EP Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

EP LAB DIGEST. 2026;26(2):15-17.

Interview by Rebecca Kapur

Dr Steinhaus is an electrophysiologist with Saint Luke’s Cardiovascular Consultants and serves as the Director of Quality and Safety for Cardiac Electrophysiology (EP) and the Institutional Review Board Co-Chair at Saint Luke’s Health System in Kansas City, Missouri. Dr Fendler is a heart failure (HF) cardiologist at Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute and assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

You have a strong collaborative approach to caring for HF patients. Could you describe what that looks like in practice today?

Steinhaus: We created what is now called the EP-Heart Failure Collaboration Clinic. It is an intentional joint clinic where both of us, EP and HF, see the patient together, at the same time, in the same room. We talk through the case beforehand, go into the room together, and evaluate the patient jointly. We also bring in the device representative so we can reprogram the device in real time. From the HF side, we can titrate meds on the spot, address symptoms, and create a plan immediately instead of going back-and-forth asynchronously.

Steinhaus: We created what is now called the EP-Heart Failure Collaboration Clinic. It is an intentional joint clinic where both of us, EP and HF, see the patient together, at the same time, in the same room. We talk through the case beforehand, go into the room together, and evaluate the patient jointly. We also bring in the device representative so we can reprogram the device in real time. From the HF side, we can titrate meds on the spot, address symptoms, and create a plan immediately instead of going back-and-forth asynchronously.

Fendler: Dan built the model based on literature showing that patients do better when EP and HF work together instead of in isolation. The concept was to treat these patients from a more holistic point of view rather than the myopic, siloed way into which modern cardiology practice can often drift.

Fendler: Dan built the model based on literature showing that patients do better when EP and HF work together instead of in isolation. The concept was to treat these patients from a more holistic point of view rather than the myopic, siloed way into which modern cardiology practice can often drift.

The patients feel attended to and appreciate that we are thinking about their case comprehensively. That means evaluating devices, optimizing medications, assessing symptoms, looking for arrhythmias, thinking about nonresponse to cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), and deciding whether therapies like CCM are appropriate—but also making sure we are not missing bigger-picture HF issues that had not been previously addressed in either EP or HF alone. It is truly collaborative care, not sequential care—that is the key difference.

What gaps or unmet needs in your clinical practice motivated you to align HF and EP programs for treating HF patients?

Fendler: The gaps were obvious before the clinic existed. CRT has decades of evidence behind it, but a substantial portion of patients do not respond. What traditionally happens is that HF sends them to EP to implant a CRT, EP implants the device, checks that it is working, and looks at capture and thresholds. However, the patient is often still short of breath, fatigued, and experiencing poor functional status. That gap, the CRT nonresponder, was the original motivation.

Steinhaus: We were missing the global perspective. Many patients were just plateauing.

Once we started doing joint visits, we realized how interconnected those issues really were.

So the collaboration grew from a simple question about whether we could do better for CRT patients into an entire care model that has expanded well beyond that initial scope. It has changed the way we both think about these patients.

Fendler: Another gap was the one between HF and EP. HF may not send patients early enough, and EP may perform an implant and never check back to see if the patient improved. Patients can get stuck in that disconnect.

The third gap was that there are now more device-based therapies available for symptomatic HF patients—CCM being one of the most evidence based. For years, options were limited beyond guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) and CRT. But CCM is opening a whole new therapeutic lane that requires both specialties to think together. So, aligning HF and EP became not just beneficial, but necessary.

We knew the need was there long before we formalized the program. The clinic just gave us the infrastructure to do the work we felt was missing.

Do you recall how this collaboration began? Was it prompted by a particular patient case or an urgent need for closer coordination?

Fendler: It was the accumulation of years of seeing these CRT patients who were still symptomatic and hearing EP colleagues say, “Why aren’t you sending me these patients earlier?” and HF colleagues saying, “Why aren’t you telling us these patients aren’t doing well after the implant?”

Then Dan came to me and the other HF specialists and said, “Why don’t we build one of these CRT optimization clinics we have heard about at conferences and in the literature?” It was an immediate yes from all of us. We knew the need, and we were already talking informally about these problems all the time.

Once we started the clinic, it became clear that seeing patients together in one room was incredibly efficient, and also rewarding. It was immediately clear how much patients valued being seen by 2 subspecialists thinking collaboratively.

Steinhaus: Now that the clinic exists, it opens up more questions such as how do we identify patients earlier, how do we refine patient selection, how do we use CCM or other therapies more effectively, and how do we streamline the workflow? We knew we needed a dedicated structure to review these patients more thoughtfully.

What is CCM, and why was it a logical choice for your collaborative approach?

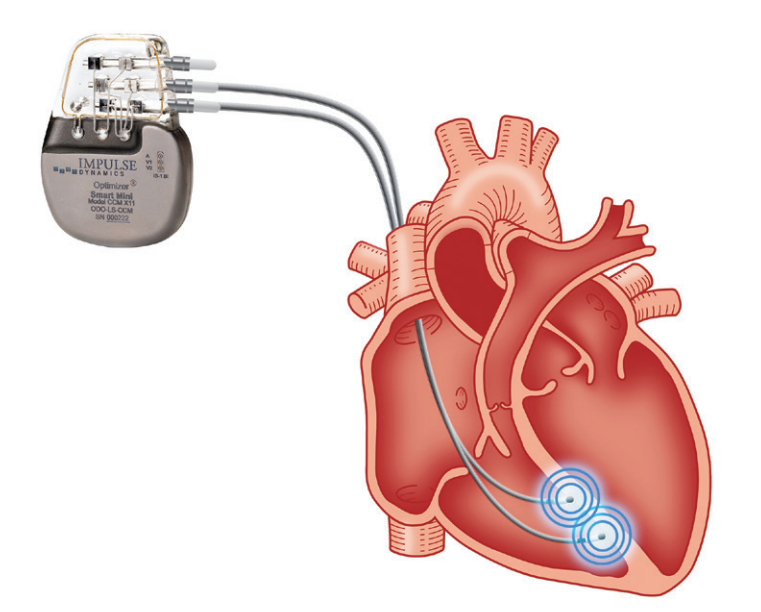

Steinhaus: CCM has become a big part of why our clinic works the way it does. CCM is a device-based therapy that is gaining more recognition as we get better at managing symptomatic HF patients who fall into that “in-between” zone. These are the NYHA Class III patients with an ejection fraction (EF) of 25% to 45% who remain symptomatic despite optimized GDMT. Importantly, many of them are not candidates for CRT. Maybe they do not have left bundle branch block, a wide enough QRS duration, or have already received CRT and did not respond. CCM fills that gap.

The device looks like a pacemaker from an implant standpoint, but the therapy itself is totally different. Instead of delivering pacing to initiate or synchronize contraction, CCM delivers relatively large electrical impulses after the R-wave to help augment contraction. Initially those impulses alter calcium handling in the myocardium. Then there is a downstream effect where CCM shifts protein expression in the myocardium toward a more normal phenotype instead of a HF phenotype. Because of that, even though the impulses are delivered via leads on the ventricular septum, global myocardial changes are seen over time. It is not just a localized effect.

From the EP standpoint, CCM is easy to adopt. Anyone who implants pacemakers can implant CCM devices. There is no special training needed because the technique is so similar.

This is exactly the type of therapy that demands collaboration. HF physicians identify the symptomatic patients and determine medical optimization. EP physicians evaluate the conduction system, device history, prior CRT response, and implant feasibility. Together, we select the right patients and follow them through therapy. It is a good example of how combining specialties can help identify and treat patients who might otherwise fall through the cracks.

Fendler: We are in a really exciting era in HF care in this country, and CCM is a big part of that.

HF guidelines are built on rigorous evidence—randomized controlled trials, survival curves, and hospitalization metrics. But the truth is that guidelines have limits. They lag behind newer therapies and can bias thinking that if something does not improve survival, it has no value. But what about the patients who are alive because we treated their myocardial infarction, ventricular tachycardia (VT), or valve disease, but they now live with debilitating HF symptoms despite being on all the right guideline-directed therapies? Historically, we did not have much else to offer, instead consigning these patients to just trying to live with the symptoms. That’s where CCM fits. It is remarkable. From an HF perspective, CCM gives us something we have needed for years: a device therapy that improves symptoms and functional status for patients who are still symptomatic, in whom GDMT alone has just not been enough.

That is why it was such a logical therapy to adopt in this collaborative model. These are the exact patients who benefit from joint care: patients with residual symptoms and still-reduced EF.

What challenges did you encounter when developing this program? In hindsight, what is one thing you would approach differently and one thing you would replicate?

Steinhaus: There were some initial worries about whether patients would need to pay 2 copays or if they would feel overwhelmed by seeing 2 specialists in one visit. But we found that patients loved it—since they needed 2 visits anyway, this saved them time. Since the billing structure supports 2 visits, we were able to sustain the model without financial drawbacks.

Once everyone became comfortable with the workflow, the clinic ran remarkably smoothly.

If I had to change anything, I would have started sooner. Seeing what this clinic has grown into, I wish we had implemented it years earlier. The benefits for patients and for us became obvious very quickly.

Fendler: The main challenge is always the same when starting any program: someone needs to be the champion. You need someone willing to build workflows, educate colleagues, and keep pushing when adoption is slow. In this case, that was Dan, and then me, and then the other HF and EP specialists who joined. It took time and effort and a lot of communication.

The other challenge was colleague buy-in. When we introduced CCM, for example, there were a few clinicians who were eager early adopters. However, most others were initially skeptical. We continued sharing evidence—KCCQ-12 improvements, echocardiography results, patient stories, and fewer HF admissions—to answer questions and address concerns. Over time, as the outcomes became more evident, gaining buy-in became much easier.

What early signs or indicators suggested that the program was successful?

Steinhaus: The clearest sign was the intervention rate. We looked at our data early on and realized that nearly 100% of patients seen in the collaborative clinic ended up with some meaningful intervention, whether that was a device programming change, medication adjustment, additional testing, or discussion about advanced therapies.

Fendler: Yes, the intervention rate was nearly 100%. Literally every time we saw a patient, we changed something meaningful, including GDMT titration, referrals to the valve clinic or atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation, evaluation for CCM, CRT vector changes, or moving toward a left ventricular assist device/transplant in advanced cases. That was the first immediate sign that the model was doing what it was supposed to do.

Steinhaus: Another major sign was the patient feedback. Patients repeatedly told us how much they appreciated having us jointly evaluate their case, and not being handed off between 2 separate clinics. It made them feel like we were treating them as a complete patient.

Clinically, too, we saw signs of benefit. Patients who had plateaued began responding to therapy once programming was optimized or once we identified them for CCM. HF physicians were able to titrate drugs they previously could not. Outcomes improved. Those early wins created momentum, and the program quickly became a mainstay of our practice.

Fendler: Then there were the patient-reported outcomes, especially the KCCQ-12 scores. We collect these on every patient. For CCM patients, they are collected pre- and post-implant. Watching those numbers improve in responders, sometimes as much as from 30 to 65, from 40 to 70, is incredibly validating. Patients shared that they walked in from the parking lot without stopping and that they feel like themselves again.

Those KCCQ-12 improvements, plus echocardiography improvements such as EF trending upward, plus fewer HF admissions, are all real indicators of success.

Another indicator was that our colleagues started reaching out to us with referrals for possible CCM candidates. That was a big shift.

How have patient selection criteria and care workflows evolved as HF and EP programs have become more integrated?

Fendler: When we started, it was strictly a CRT nonresponder clinic. However, the biggest change came with patient selection. We expanded from CRT nonresponders to patients with complex AF, VT, or persistent HF symptoms despite GDMT; this also includes patients who might benefit from CCM, patients who need optimization of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator or CRT-D programming, patients who are drifting toward advanced HF pathways, and patients recently admitted with HF, identified proactively via the electronic medical record.

If you could share one key insight for building a successful collaborative program, what would it be?

Steinhaus: I think people imagine that it is going to be too much work, time-consuming, complicated, or that there is no clear benefit. However, this has been one of the most rewarding and productive things we have done. It has completely changed how we practice. It opened up the HF group to more device-based therapies and opened the EP group to the broader context of HF care. It has created a constant back-and-forth dialogue that makes all of us better at what we do.

If someone wants to start something similar, I would tell them that it does not have to be a whole clinic at first. Find one HF or EP physician who cares about optimizing shared patients and ask to collaborate on the next 5 patients. If it works, then expand, and if not, then pivot. Once you start, it becomes obvious how beneficial it is.

Fendler: Again, you absolutely need a champion. Building something new requires a lot of extra work, and you need someone who is willing to put in the time.

Communicate differently with different stakeholders, as everyone needs to hear the message in a different way. That is the part that Dan and I do well. We bring data. We bring patient stories. We explain the clinical rationale. We show KCCQ-12 improvements. We show echocardiography improvements. We try to make the “why” clear.

Do you have a patient story you can share that shows the value of this collaborative practice in treating HF?

Steinhaus: There are many, but CCM has provided some of the best examples. We had several patients who had dilated cardiomyopathy and had received CRT, but they were not responding. Their KCCQ scores were in the 30s or 40s. They were barely functioning and felt exactly the same after CRT implantation as they did before. But when we looked at their devices, there was good lead position, good pacing percentages, and appropriate vectors.

These are the patients where CRT did not help. So now what? That is exactly the type of patient CCM was designed for. We tried CCM in several of these scenarios. The first couple of patients came back saying things like: “I was not able to carry groceries up the stairs before, but now I can.”

CCM works incredibly well for many. What is also interesting is how CCM interacts with medications. A lot of these patients were so orthostatic or hypotensive that HF physicians could not titrate their medications at all. Once CCM was in place, blood pressure improved, the patient felt better, and suddenly we could add more GDMT. That combination of device plus optimized pharmacology is powerful. Additionally, Medicare now covers CCM, significantly expanding access to this therapy for a much larger population of eligible patients.

Many patients also went to cardiac rehab afterward and started walking more, improving conditioning and boosting heart rate response. The downstream benefits are real. I would say CCM has been one of the biggest success stories in the collaborative clinic because it is exactly the type of therapy that would not always be considered if EP and HF were not working together.

Fendler: CCM really showcases the value of this joint clinic because these patients often would not have been identified for CCM without the EP-HF collaboration. If the care model was siloed, these patients might have stayed stuck. But because of the collaborative clinic, we are able to see the entire picture a bit better.

These successes change the mindset of the whole team: EP, HF, nurses, technicians, and administrators. When everyone sees patients getting better because we combined device therapy with HF therapy in a collaborative way, they become believers in the model and the therapy.

What would you say to someone who believes this approach could never work in their practice?

Fendler: Start small. Start by talking with one colleague, HF or EP, about one patient. Repeat the process and formalize it when you feel the momentum.

Steinhaus: You just need one partner on the other side, EP or HF, who cares about optimizing shared patients.

Fendler: This approach works because it mirrors how patients experience their disease. They don’t experience HF on Monday and arrhythmias on Tuesday. Their conditions exist together, so the care should exist together as well. The thing that will make it all work is believing that the patient deserves integrated care instead of siloed care. Once you believe that, the rest follows.

Steinhaus: Patients absolutely experience the benefit. So, just start the conversation.

The transcripts were edited for clarity and length.

Individual results may vary. This information is not intended to guarantee outcomes and may not be indicative of every patient’s experience.

This content was published with support from Impulse Dynamics.

Disclosures: Dr Steinhaus and Dr Fendler have completed and returned the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr Steinhaus reports support from Impulse Dynamics for the present manuscript and honoraria from Impulse Dynamics for speaking engagements. Dr Fendler reports support from Impulse Dynamics for the present manuscript, investigator-initiated study grant support from Abbott Laboratories, consulting fees from Precision Cardiovascular, honoraria from Impulse Dynamics for a podcast recording, support from Impulse Dynamics for travel (for a presentation at educational event), support from Precision Cardiovascular for travel and registration for a scientific meeting, and participation on an Advisory Board (Impulse Dynamics).