Long-Term Outcomes of Excimer Laser Coronary Angioplasty in Severely Calcified De Novo Coronary Lesions: A Retrospective Single-Center Study

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Cath Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Giancarla Scalone1; Luca di Vito1; Alessandro Aimi2; Eliana Carapellucci1; Luca Mariani3; Anita Merani4; Francesco Orazi1; Simona Silenzi1; Pierfrancesco Grossi1

1Interventional Cardiology Department, Mazzoni Hospital, Ascoli Piceno, Italy;

2Interventional Cardiology Department, Santa Maria della MisericordiaHospital, Perugia, Italy;

3Interventional Cardiology Department, Ospedali Riuniti, Ancona, Italy

4Interventional Cardiology Department, Ferrara University, Ferrara, Italy.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

The authors can be contacted via Giancarla Scalone MD, PhD, at gcarlascl@gmail.com.

Abstract

Background. Excimer laser coronary angioplasty (ELCA) is increasingly recognized as a valuable tool for treating severely calcified plaques. In this single-center, retrospective study, we sought to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ELCA in the management of severely calcified de novo coronary lesions and explore its potential long-term benefits.

Methods and results. Between January 1, 2014 and December 22, 2024, 50 patients who underwent ELCA for angiographically confirmed, severely calcified coronary plaques or uncrossable lesions were retrospectively included. The mean patient age was 76.6 ± 8.2 years, with a male preponderance (74%). Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) was the presentation in 76% of cases.

The minimum lumen diameter increased from 0.40 mm2 (IQR 0.10-0.90) before percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to 1.1 mm2 (IQR 0.40-1.8) after ELCA. Angiographic success, defined as residual stenosis <20%, was achieved in 96% of cases. Intravascular ultrasound was employed in 18% of procedures, showing a median final stent expansion of 81% (IQR 70-96).

Three procedural dissections (6%) occurred and were successfully managed with stent implantation. At median follow-up of 85 months (IQR 10-130), 10 all-cause deaths (20%) were recorded. The median time to event was 64 months (IQR 24-127), with a median age at death of 86 years (IQR 69-89).

Age at the time of PCI was the only independent predictor of adverse events (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.006-0.032, P=.004).

Conclusions. This retrospective real-world analysis suggests that ELCA is a safe and effective option for treating severely calcified de novo coronary lesions, with favorable long-term outcomes.

Read the commentary to this study by Scalone et al:

Sustained Safety and Success: Long-Term Data Support the Role of Excimer Laser Atherectomy

Akiva Rosenzveig, MD; Robert S. Dieter, MD; Ayesha Nawaz, MD; Merlin Nikita, MD;Thomas Callahan, MD; Aravinda Nanjundappa, MD

Heavily calcified coronary plaques can pose challenges during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) as these plaques are associated with lower rates of complete revascularization, increased peri-procedural complications, and poorer clinical outcomes.1-4 Over the past 25 years, interest has been increasing in excimer laser coronary angioplasty (ELCA) as a valuable tool in the PCI armamentarium for the management of heavily calcified plaques, owing to its ability to modify undilatable and uncrossable coronary lesions.5-10 However, the evidence supporting the efficacy and safety of ELCA in the setting of de novo coronary lesions remains limited, consisting mostly of non-randomized studies with short-term follow-up.11

In this single-center, retrospective study, we sought to investigate the efficacy and safety of ELCA in the treatment of severely calcified de novo coronary lesions, and identify any potential benefits at long-term follow-up.

Methods

This single-center, retrospective, observational study included 50 consecutive patients who underwent ELCA-assisted PCI for severely calcified de novo coronary lesions between January 1, 2014 and December 22, 2024.

ELCA was used at operator discretion in cases of angiographically confirmed, severely calcified coronary plaques or in all cases of the inability of the smallest balloon or microcatheter to cross the lesion. Severely calcified lesions were angiographically defined as radiopacities observed on fluoroscopy, without cardiac motion before contrast injection, compromising one or both sides of the lumen.12

Vascular access was obtained using 6 French sheaths via the left or right radial arteries. A 0.9 mm ELCA catheter was used with a minimum fluency of 80 mJ/mm2. The number of laser pulses was according to operator preference.

Saline flush and “bathe technique” were used to clear the blood and dye during delivery of the therapy, with the catheter advanced in small increments during 10-second bursts of lasing.

Clinical characteristics of the patients were collected at the time of procedure.

Quantitative coronary angiography analysis was performed offline. Lesion length (including the stented segment plus 5 mm proximal and distal margins), reference vessel diameter (RVD), and minimal lumen diameter (MLD) before PCI and after ELCA were measured using the outer catheter diameter as the calibration standard. Angiographic success was defined as residual stenosis <20% after PCI.

Two independent researchers reviewed the angiographic sequences, and average values were used for analysis. Additional procedural characteristics were recorded: diameter and the length of the implanted stents, the number and diameter of the noncompliant (NC) balloons and their maximum diameter, and the number of scoring balloons. The choice to employ intravascular imaging was left to the operator. The fluoroscopy time was also evaluated.

The following periprocedural complications were recorded and verified: perforation, dissection, tamponade, and distal embolization. Perforation was defined as the demonstration of a persistent extravascular collection of contrast medium beyond the vessel wall. Major dissection was defined as type C or worse, and minor dissection was defined as type A or B, according to the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute classification.13

Patients were followed during hospitalization and afterward through outpatient visits for up to 130 months post PCI. Major adverse cardiac events (MACE) included death for any cause, myocardial infarction (MI), cardiac death, and target lesion revascularization.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical Analysis

Data distribution was assessed according to the Kolgormonov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test, as appropriate, and are reported as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range [IQR]). Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. Event-free survival was calculated from the procedure date to death. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to estimate cumulative mortality. Independent predictors of survival were assessed via Cox proportional hazards regression model, and results are presented as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A P-value<.05 was established as the level of statistical significance for all tests. SPSS 17.0 statistical software (SPSS Italia, Inc.) was used for analyses.

Results

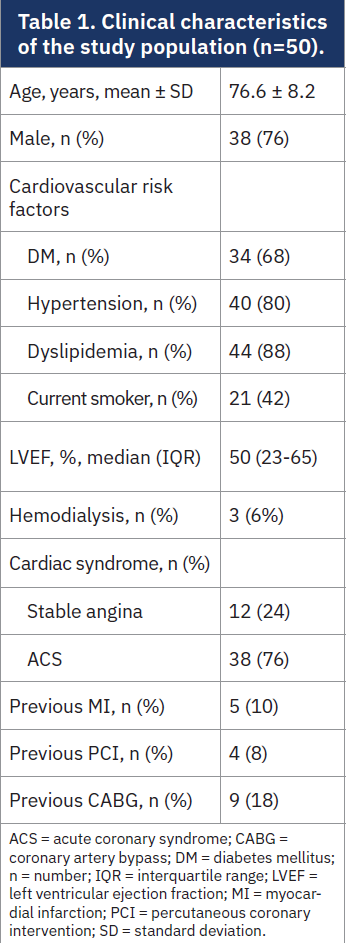

Patient clinical characteristics are reported in Table 1. The mean age was 76.6 ± 8.2 years, with a male preponderance (76%). Among the included patients, 68% had diabetes, 80% had hypertension, and 88% had dyslipidemia. Thirty-eight patients (76%) presented with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), while 12 (24%) were treated electively for stable angina. Thirteen patients had received a prior revascularization with either PCI (8%) or coronary artery bypass (18%), and 5 (10%) had a history of previous MI. Median left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 50% (IQR 23-65).

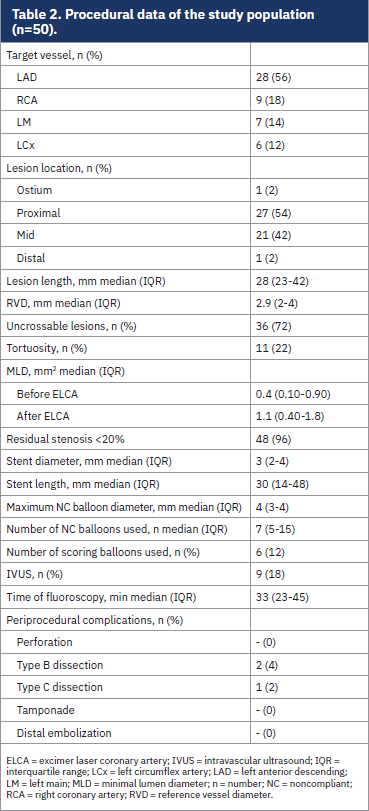

Procedural characteristics are reported in Table 2. The target vessel was most often the left anterior descending artery (56%), followed by the right coronary artery (18%), left main (14%), and circumflex artery (12%). Lesions were in the proximal segment in 54% of cases, in the mid segment in 42%, and in the ostial or distal segment in 2% of cases. Lesion tortuosity was present in 22% of cases. ECLA was used for uncrossable lesions in 72% of cases. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) was employed in 9 procedures (18%), to assess final stent expansion. Median lesion length was 28 mm (IQR 23-42), with a median RVD of 2.9 (IQR 2-4). Median pre-PCI MLD was 0.40 mm2 (IQR 0.10-0.90), increasing to 1.1 mm2 (IQR 0.40-1.8) after ELCA. Angiographic success (residual stenosis<20%) was achieved in 96% of cases. Only drug-eluting stents (DES) were implanted. The median stent diameter and length were 3 mm (IQR 2-4) and 30 mm (IQR 14-48 mm), respectively.

Procedural characteristics are reported in Table 2. The target vessel was most often the left anterior descending artery (56%), followed by the right coronary artery (18%), left main (14%), and circumflex artery (12%). Lesions were in the proximal segment in 54% of cases, in the mid segment in 42%, and in the ostial or distal segment in 2% of cases. Lesion tortuosity was present in 22% of cases. ECLA was used for uncrossable lesions in 72% of cases. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) was employed in 9 procedures (18%), to assess final stent expansion. Median lesion length was 28 mm (IQR 23-42), with a median RVD of 2.9 (IQR 2-4). Median pre-PCI MLD was 0.40 mm2 (IQR 0.10-0.90), increasing to 1.1 mm2 (IQR 0.40-1.8) after ELCA. Angiographic success (residual stenosis<20%) was achieved in 96% of cases. Only drug-eluting stents (DES) were implanted. The median stent diameter and length were 3 mm (IQR 2-4) and 30 mm (IQR 14-48 mm), respectively.

A median of 7 NC balloons were used per procedure (IQR 5-15), with a maximum balloon diameter of 4 mm (IQR 2-4). Scoring balloons were employed in 6 cases (12%).

IVUS-assessed final stent expansion showed a median value of 81% (IQR 70-96). Median fluoroscopy time was 33 minutes (IQR 23-43).

Regarding the intraprocedural complications, 3 procedural dissections (6%) were observed, all managed successfully with stent implantation. No MACE occurred during hospitalization.

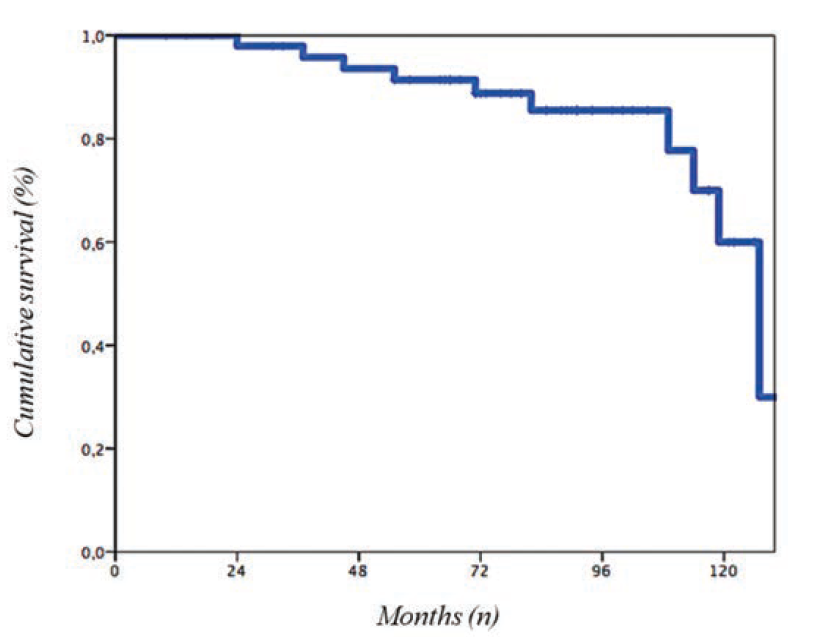

At median follow-up of 85 months (IQR 10-130), there were 10 all-cause deaths (20%). The median time to event was 64 months (IQR 24-127), with a median age at death of 86 years (IQR 69-89) (Figure).

At the univariate analysis, age at the time of PCI was the only independent predictor of death (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.006-0.032, P=.004).

Discussion

The main findings of our retrospective, real-world study are as follows:

1. ELCA was associated with a high procedural success rate in the treatment of severely calcified de novo coronary lesions, even in a population predominantly composed of elderly patients presenting with ACS;

2. The lack of cardiac events at a long-term follow-up suggests that ELCA may offer durable clinical benefits in this high-risk setting;

3. Age was the only independent predictor of all-cause of mortality.

In recent years, ELCA has attracted renewed interest for the treatment of complex coronary disease, including in-stent restenosis (ISR),14 debulking of saphenous vein graft lesions,15 facilitating chronic total occlusion interventions,16 and treating thrombotic lesions17.

Despite this, the overall utilization of ELCA remains relatively low. This may partly be due to the higher complications rates reported during PCI with the use of ELCA. Complications with ELCA are significantly greater than interventions without the use of ELCA,18 although these rates vary depending on lesion complexity and anatomical characteristics. Evaluating the efficacy and safety of ELCA in specific coronary scenarios is challenging due to the predominance of retrospective studies, heterogeneity in lesion types, and small sample sizes within subgroups.11

Recently, Jurado et al19 conducted the first randomized trial comparing 3 advanced plaque modification techniques: rotational atherectomy, ELCA, and intravascular lithotripsy, in the treatment of calcified coronary lesions. They concluded that all three methods demonstrated comparable efficacy and safety, emphasizing their complementary roles. The selection of plaque modification technique should therefore be individualized based on patient profile and lesion characteristics.

Our real-word data support the findings of Jurado et al in the context of ELCA and, to our knowledge, offer the longest follow-up reported to date for this modality. Our cohort was older than those in prior studies,20,21 and 76% presented with ACS. Despite this, no stent-related adverse events were recorded during follow-up. Notably, the 20% rate of MACE was entirely due to all-cause mortality, occurring at a mean age of 86 years, with age emerging as the sole predictor of these events.

Use of IVUS was low (18%) and employed primarily to assess the final stent expansion. The limited use of IVUS likely reflects the challenging nature of these lesions, many of which were uncrossable at baseline, discouraging operators from employing imaging modalities at the initial stage. Moreover, these procedures were performed over a long period, during which the routine use of intracoronary imaging in such complex PCI was not yet widely recommended.22,23

Study Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective, single-center study with a relatively small sample size. Second, the absence of intracoronary imaging at the start of procedure limited our ability to characterize the nature of the calcium and therefore identify the coronary lesions that could best benefit from ELCA use.22,23

Conclusions

Our retrospective, real-world data suggest that ELCA is an effective and safe option for treating severely calcified de novo coronary lesions, even in elderly patients with multiple cardiovascular risk factors and predominant ACS presentation. The lack of cardiac events at long-term follow-up indicates a potential sustained benefit of ELCA in this setting. However, further larger prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings and better define the role of ELCA in contemporary PCI practice.

Read the commentary to this study by Scalone et al:

Sustained Safety and Success: Long-Term Data Support the Role of Excimer Laser Atherectomy

Akiva Rosenzveig, MD; Robert S. Dieter, MD; Ayesha Nawaz, MD; Merlin Nikita, MD;Thomas Callahan, MD; Aravinda Nanjundappa, MD

References

1. Kobayashi Y, Okura H, Kume T, et al. Impact of target lesion coronary calcification on stent expansion. Circ J. 2014; 78: 2209-2214.

2. Huisman J, van der Heijden LC, Kok MM, et al. Impact of severe lesion calcification on clinical outcome of patients with stable angina, treated with newer generation permanent polymer-coated drug-eluting stents: a patient-level pooled analysis from TWENTE and DUTCH PEERS (TWENTE II). Am Heart J. 2016; 175:121-129.

3. Tzafriri AR, Garcia-Polite F, Zani B, et al. Calcified plaque modification alters local drug delivery in the treatment of peripheral atherosclerosis. J Control Release. 2017; 264:203-210.

4. Copeland-Halperin RS, Baber U, Aquino M, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and impact of coronary calcification on adverse events following PCI with newer-generation DES: Findings from a large multiethnic registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018; 91:859-866.

5. Reifart N, Vandormael M, Krajcar M, et al. Randomized comparison of angioplasty of complex coronary lesions at a single center. Excimer Laser, Rotational Atherectomy, and Balloon Angioplasty Comparison (ERBAC) Study. Circulation. 1997; 96: 91-98.

6. Appelman YE, Piek JJ, Strikwerda S, et al. Randomised trial of excimer laser angioplasty versus balloon angioplasty for treatment of obstructive coronary artery disease. Lancet. 1996; 347: 79-84.

7. Latib A, Takagi K, Chizzola G, et al. Excimer Laser LEsion modification to expand non-dilatable stents: the ELLEMENT registry. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2014; 15: 8-12.

8. Yin D, Maehara A, Mezzafonte S, et al. Excimer laser angioplasty-facilitated fracturing of napkin-ring peri-stent calcium in a chronically underexpanded stent: documentation by optical coherence tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015; 8: e137-e139.

9. Ashikaga T, Yoshikawa S, Isobe M. The effectiveness of excimer laser coronary atherectomy with contrast medium for underexpanded stent: the findings of optical frequency domain imaging. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015; 86: 946-949.

10. Lee T, Shlofmitz RA, Song L, et al. The effectiveness of excimer laser angioplasty to treat coronary in-stent restenosis with peri-stent calcium as assessed by optical coherence tomography. EuroIntervention. 2019; 15: e279-e288.

11. Nishino M, Mori N, Takiuchi S, et al. ULTRAMAN Registry investigators. Indications and outcomes of excimer laser coronary atherectomy: efficacy and safety for thrombotic lesions—the ULTRAMAN registry. J Cardiol. 2017; 69: 314-319.

12. Mintz GS, Popma JJ, Pichard AD, et al. Patterns of calcification in coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1995; 91: 1959-1965.

13. Huber MS, Mooney JF, Madison J, Mooney MR. Use of a morphologic classification to predict clinical outcome after dissection from coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 1991; 68: 467-471.

14. Pal N, Din J, O’Kane P. Contemporary management of stent failure: part one. Interv Cardiol. 2019; 14: 10-16; EuroIntervention. 2019; 15: e279-e288.

15. Niccoli G, Belloni F, Cosentino N, et al. Case-control registry of excimer laser coronary angioplasty versus distal protection devices in patients with acute coronary syndromes due to saphenous vein graft disease. Am J Cardiol. 2013; 112: 1586-1591.

16. Rinfret S, ed. Percutaneous Intervention for Coronary Chronic Total Occlusion: The Hybrid Approach. Springer; 2016.

17. Topaz O, Minisi AJ, Bernardo NL, et al. Alterations of platelet aggregation kinetics with ultraviolet laser emission: the “stunned platelet” phenomenon. Thromb Haemost. 2001; 86: 1087-1093.

18. Reifart N, Vandormael M, Krajcar M, et al. Randomized comparison of angioplasty of complex coronary lesions at a single center. Excimer Laser, Rotational Atherectomy, and Balloon Angioplasty Comparison (ERBAC) study. Circulation. 1997; 96: 91-98.

19. Jurado-Román A, Gómez-Menchero A, Rivero-Santana B, et al. Rotational atherectomy, lithotripsy, or laser for calcified coronary stenosis: the ROLLER COASTR-EPIC22 trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2025; 18: 606-618.

20. Bilodeau L, Fretz EB, Taeymans Y, et al. Novel use of a high-energy excimer laser catheter for calcified and complex coronary artery lesions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2004; 62: 155-161.

21. Ambrosini V, Sorropago G, Laurenzano E, et al. Early outcome of high energy Laser (Excimer) facilitated coronary angioplasty ON hARD and complex calcified and balloOn-resistant coronary lesions: LEONARDO study. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2015; 16: 141-146.

22. Di Mario C, Koskinas KC, Räber L. Clinical benefit of IVUS guidance for coronary stenting: the ultimate step toward definitive evidence? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72: 3138-3141.

23. De Maria GL, Scarsini R, Banning AP. Management of calcific coronary artery lesions: is it time to change our interventional therapeutic approach? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019; 12: 1465-1478.