Grit and Curiosity – Keys to Success in the Cath Lab

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Cath Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Morton J. Kern, MD, MSCAI, FACC, FAHA

Clinical Editor; Interventional Cardiologist, Long Beach VA Medical Center, Long Beach, California; Professor of Medicine, University of California, Irvine Medical Center, Orange, California

Disclosures: Dr. Morton Kern reports he is a consultant for Abiomed, Abbott Vascular, Philips, ACIST Medical, and Opsens Inc.

Dr. Kern can be contacted at mortonkern2007@gmail.com

On X @MortonKern

Click here for a PDF of this article, courtesy of Cath Lab Digest.

After Thanksgiving dinner, my family’s conversation moved to issues of successes and failures. I asked, “What is the single most powerful personality trait that predicts success?”, having heard this question on a TED talk by psychologist Angela Duckworth. My niece, a geology professor, answered immediately, “Grit.”

“How did you know that?” I asked. She said she had read it years ago in an article by Dr. Duckworth.1 I was surprised that someone even knew what grit was, as I had just learned about it. But I was sure that there’s more to it than just having grit. I think success, especially in research or medicine, requires a strong dose of curiosity. Let’s define some terms before we argue the point.

Grit = Effort x Time

Grit is defined as passion (love of a subject, idea, or goal) coupled with a sustained effort to meet this passion over a prolonged period; that is, having perseverance toward achieving that goal. “Gritty” people put in sustained effort over a long time to achieve their goal. It means that grit has 2 essential components: 1) finding or defining your passion (which involves a sense of purpose) and 2) persevering against obstacles.

As I mentioned above, psychologist Angela Duckworth brought the concept of “grit” to the public, providing evidence that talent and luck aren’t all that matter for success. Duckworth and her colleagues published research in 2007 introducing the Grit Scale to analyze success, such as educational achievement, persistence at a military academy, and winning a spelling bee.2

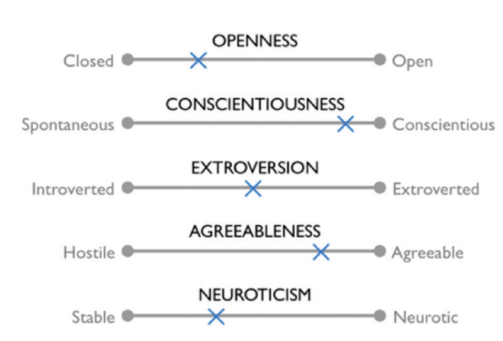

Reprinted from Lim A. The big five personality traits. Simply Psychology. 2020 June 15. Accessed January 9, 2025. https://www.simplypsychology.org/big-five-personality.html

Grit is similar to conscientiousness, one of the Big Five personality traits (Figure 1). People high in this trait are disciplined, dependable, careful, and goal-directed. It is worth noting that successful people often share qualities like talent, intelligence, conscientiousness, and optimism, among others.

Curiosity

Curiosity is a strong desire to know or learn something. Webster’s Dictionary also defines it as a strange or unusual object or fact, but that’s not what we’re talking about. Curious people are often eager, inquiring, observant, and intellectual. Curiosity is a fundamental human characteristic that motivates exploration and discovery, leading to personal growth and creativity. It is often associated with enhanced problem-solving skills since curious people read, ask questions, and examine their world beyond the immediate environment.

A curious person persistently asks, “Why?” and then seeks an answer. This persistence in the quest to answer key questions is why I believe curiosity is a big part of one’s success story.

Curiosity – My Personal Story

Downey, California, 1960 (age 10). I recall as a boy invading my father’s workshop and handling all the different tools wondering, “what’s this for?”, “how does it work?”, “Why would someone have this?”. My father, a family practice physician, loved to tinker, share stories of success and failure, and curiosities in medical practice. He let me know I was free to explore everything in the house, workshop and yard. I gravitated to the scientific aspects of my explorations. Why did a magnifying glass burn a piece of paper or an ant walking by? Several of my experiments ended badly. My Dad would bring home glassware from an old chemistry lab, flasks, alcohol flame burners, test tubes, and metal clamps to hold them. I read about Alexander Fleming and how he discovered penicillin from bread mold. I thought I’d try to make some in the kitchen (remember, I am 11 years old). In one of my father’s test tubes, I put pieces of moldy bread from a petri dish I incubated in the refrigerator. I added alcohol (from where I got this, I don’t recall) and mixed it with the moldy bread. I then started to cook it over the flame of the glass sterilizing bottle. At first it bubbled, then boiled, then ignited and flew out of the test tube, catching my 4-year-old brother’s pajama sleeve on fire. I quickly put it out, no harm done, but I caught hell for that piece of curious science. After a prolonged timeout, I was wiser but undaunted.

Downey, California, 1960 (age 10). I recall as a boy invading my father’s workshop and handling all the different tools wondering, “what’s this for?”, “how does it work?”, “Why would someone have this?”. My father, a family practice physician, loved to tinker, share stories of success and failure, and curiosities in medical practice. He let me know I was free to explore everything in the house, workshop and yard. I gravitated to the scientific aspects of my explorations. Why did a magnifying glass burn a piece of paper or an ant walking by? Several of my experiments ended badly. My Dad would bring home glassware from an old chemistry lab, flasks, alcohol flame burners, test tubes, and metal clamps to hold them. I read about Alexander Fleming and how he discovered penicillin from bread mold. I thought I’d try to make some in the kitchen (remember, I am 11 years old). In one of my father’s test tubes, I put pieces of moldy bread from a petri dish I incubated in the refrigerator. I added alcohol (from where I got this, I don’t recall) and mixed it with the moldy bread. I then started to cook it over the flame of the glass sterilizing bottle. At first it bubbled, then boiled, then ignited and flew out of the test tube, catching my 4-year-old brother’s pajama sleeve on fire. I quickly put it out, no harm done, but I caught hell for that piece of curious science. After a prolonged timeout, I was wiser but undaunted.

Curiosity in Cardiology Research

Boston, the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 1979. I’m a first-year cardiology fellow, surrounded by brilliant minds asking questions, working on research projects in their various stages of development. Many of my colleagues would go on to answer critical questions impacting heart patients around the world. I had no idea how to do a research project or where this path would lead. I initially thought I’d be a doctor like my father and just take care of patients. But I it wasn’t long before I was assigned to my first research project on coronary sinus blood flow, headed by Dr. John Rutherford (now in Dallas, Southwestern University). I had no idea what this entailed, but my fog around research, methods, and ideas soon lifted as I studied cardiac physiology, reviewed medical school texts, and asked questions. I asked and learned from my co-fellows, my attendings, and the nurses in the cath lab. I read articles and book chapters on coronary blood flow. My work in the cath lab became my favorite clinical activity and doubled as my research lab. Working with patients, placing catheters, and measuring hemodynamics and coronary blood flow was stimulating and rewarding. I marveled on how the heart worked its wonders. I knew I could answer a few interesting questions now that I could measure coronary flow in patients.

Another curious experience taught me to trust but verify. We were measuring coronary sinus blood flow before and after oral ibuprofen. Things were going well and I was thinking this research stuff was straightforward. However, to my surprise, I learned that oral medications were not well absorbed in the prone patient on a cath lab table. I accidently discovered this fact when patient #12 vomited into an emesis basin. There were the 2 ibuprofen tablets, undissolved. The ibuprofen blood levels, drawn after each patient study, showed no drug was in the blood: 0 for 12 patients had received any ibuprofen. I learned to trust the process but verify the results, sooner than later. Undaunted and wiser, we successfully tested other drugs, like beta blockers on the vasoconstriction responses, then alpha-blockers, and so on. My research path to the study of coronary blood flow had taken off. I continued in the same line of research at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, 1982-1985, after which I worked with a Doppler flow wire at St. Louis University, until I moved to the University of California-Irvine in 2005 (starting my CLD clinical editor’s page in early 2006).

Over my 45 years in the cath lab, I continued to address many questions about the heart through hemodynamic studies, coronary physiologic measurements, and interventional cardiology techniques. Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) provided a unique human research model employing emerging tools, like intravascular ultrasound, angioplasty, Doppler, and pressure sensor wires, applying approaches to important problems heretofore not studied in awake patients. My curiosity has never waned. I have shared my enthusiasm with my colleagues, fellows, residents, students, nurses, and technologists through cases, lectures, papers, reviews, and conferences. I hoped this spirit was contagious, and would stimulate in others the curiosity and great experiences I had.

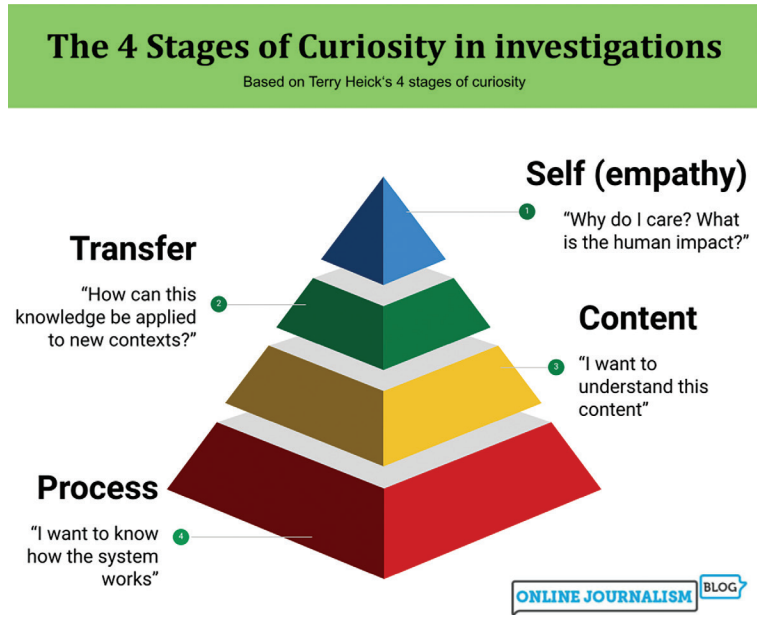

Reprinted with permission from Bradshaw P. How to use the ‘4 stages of curiosity’ as a framework for investigations. Online Journalism Blog. 2021 June 29. Accessed January 9, 2025. https://onlinejournalismblog.com/tag/4-stages-of-curiosity/

The Challenge of Research in Clinical Practice

At the beginning of their tenure in a new cath lab, the young attending physicians just out of training are challenged, having to take on the ways of their new cath lab. Adding clinical research into routine cath lab work can be difficult, and, at times, may be impossible. Research cannot be conducted at the expense of timely clinical care. In addition, research cannot be done if there is no time allotted to permit the study components (e.g. setup, drug/intervention, observation time, etc.) to go forward. If the pressure of daily caseloads is too great, there will be no research that day. Given this limitation, the attending physician’s curiosity may be dimmed but it should not be extinguished. Grit is needed to overcome such obstacles.

The Bottom Line

Success needs curiosity and grit (see Figure 2, the 4 stages of curiosity in research). How do you develop these traits? Engage your passion and begin the questioning of conventional wisdom. In your research, accept setbacks and obstacles. Do not be afraid to fail. View failure as a learning opportunity rather than a reason to quit. Lastly, surround yourself with curious people who also have grit. As lifelong learners working in cath labs, we should apply ourselves to improving techniques, learning more, seeing more, and answering more questions to advance the field and help our patients.

References

- Grit. Psychology Today. Accessed January 9, 2025. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/grit?msockid=3d2c0574b2d36c8b37ac13cab3696df3

- Duckworth A. Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance. New York, NY: Scribner; 2016.

Find More:

Renal Denervation Topic Center

Cardiovascular Ambulatory Surgery Centers (ASCs) Topic Center

Grand Rounds With Morton Kern, MD

Peripheral Artery Disease Topic Center