Do You Always Check the ACT Before Beginning PCI?

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Cath Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Morton Kern, MD, with Arnold Seto, MD, MPA, VA Long Beach, Long Beach, California; Michael Ragosta, MD, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia; Mir Basir, DO, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan.

We were discussing a tricky thrombotic complication during a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Acute stent thrombosis is a rare occurrence but in the case under review, it appears it was the result of an infiltrated intravenous (IV) line, which resulted in failure of the heparin to be delivered and hence insufficient to anticoagulate the patient. It was suggested that this complication might have been prevented if the operators had waited until they confirmed an adequate ACT (activated clotting time test). Had the ACT, which is routinely drawn shortly after heparin administration, been done, it would have been recognized as subtherapeutic.

We were discussing a tricky thrombotic complication during a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Acute stent thrombosis is a rare occurrence but in the case under review, it appears it was the result of an infiltrated intravenous (IV) line, which resulted in failure of the heparin to be delivered and hence insufficient to anticoagulate the patient. It was suggested that this complication might have been prevented if the operators had waited until they confirmed an adequate ACT (activated clotting time test). Had the ACT, which is routinely drawn shortly after heparin administration, been done, it would have been recognized as subtherapeutic.

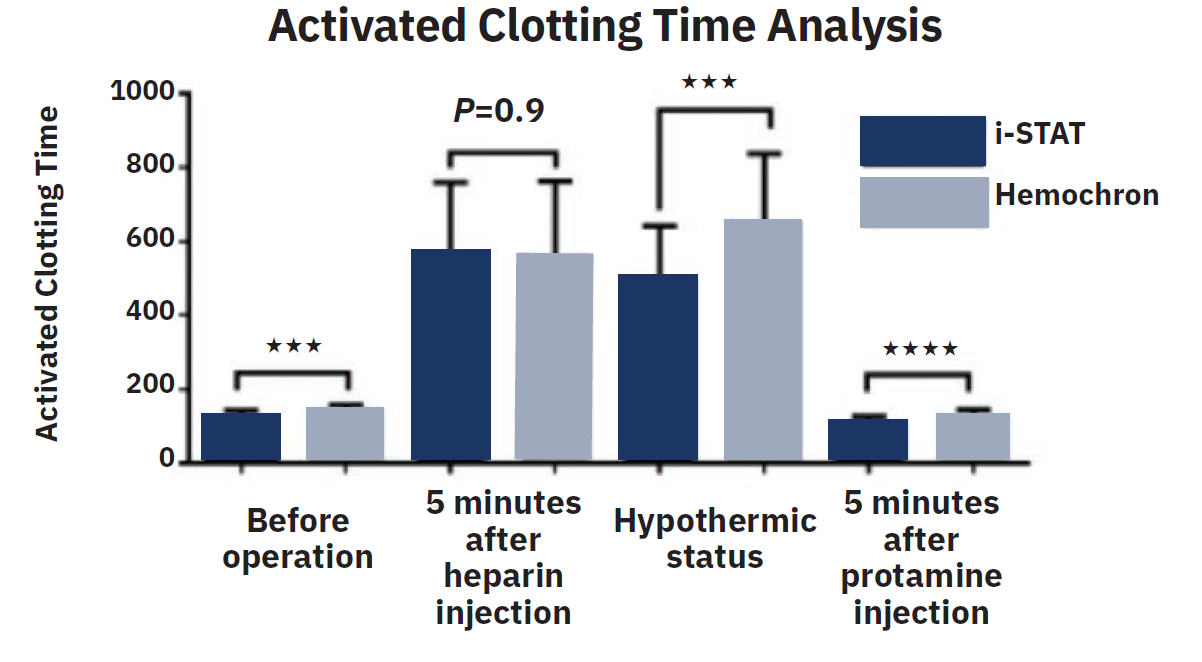

Reprinted from Wang Y, et al, Comparison of activated clotting time analyzer in cardiovascular surgery. Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research. 2018; 7(1). doi:10.26717/BJSTR.2018.07.001432. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This issue has also been addressed by the VA National Major Adverse Events Committee (VA MAEC), in response to recurrent thrombotic events and other procedural complications. The VA MAEC recommended that operators confirm that an ACT is >250 seconds (s) (normal range is 80-130s) before instrumenting a coronary artery, defined as wiring a coronary with an .014-inch guidewire. Ensuring the ACT is in the therapeutic range adds additional time (<5 minutes on average) to the procedure.

After our discussion, Dr. Seto asked:

1. Is it below the standard of care to begin an elective PCI before an ACT is returned >250s? (assume 70-100 U/kg of unfractionated heparin [UFH] has been administered). Is an ACT >200s/<250s acceptable?

2. Should an ACT >250s be required when using bivalirudin? (e.g., in case of an infiltrated IV)

3. Should the ACT >250s apply to all ACT machines? (Recall Hemochron 300-350/s [Werfen], HemoTec, Medtronic ACT Plus 250-300s, and i-STAT [Abbott Point of Care] 200-250s.) Undoubtedly, the time required to return an ACT is a factor for busy operators, especially for the i-STAT machine, which has become prevalent in many labs, but has the slowest time to result.

4. As an experienced operator, are you waiting for the ACT to return before proceeding?

Mir Basir, DO, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan:

Mir Basir, DO, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan:

1. Is it below the standard of care (SOC) to begin an elective PCI before an ACT is returned >250s?

I do think it’s below the SOC to start before an ACT is >200s. We have also had a few cases of early thrombus during elective PCI because of a poor IV.

2. Should an ACT >250s be required when using bivalirudin? (in case of an infiltrated IV, for instance).

Yes, similarly, we ask for a one-time check to make sure ACT is >300s in bivalirudin cases so we know the IV is working well. We also had a case where the IV was fine, then stopped working during a case with thrombotic complication, but I don’t use a lot of bivalirudin.

3. Should the ACT >250s apply to all ACT machines? (Recall Hemochron 300-350s, Hemotec, Medtronic ACT Plus 250-300s and, i-STAT 200-250s).

I’m not sure, but that [rule] fits our model. Undoubtedly, the time required to return an ACT is a factor for busy operators, especially for the i-STAT machine, which has become prevalent in many labs, but has the slowest time to result.

4. Are you waiting for the ACT to return before proceeding?

Yes, I do wait, because we’ve seen the above complications in other cases. I wait until the ACT is >200s.

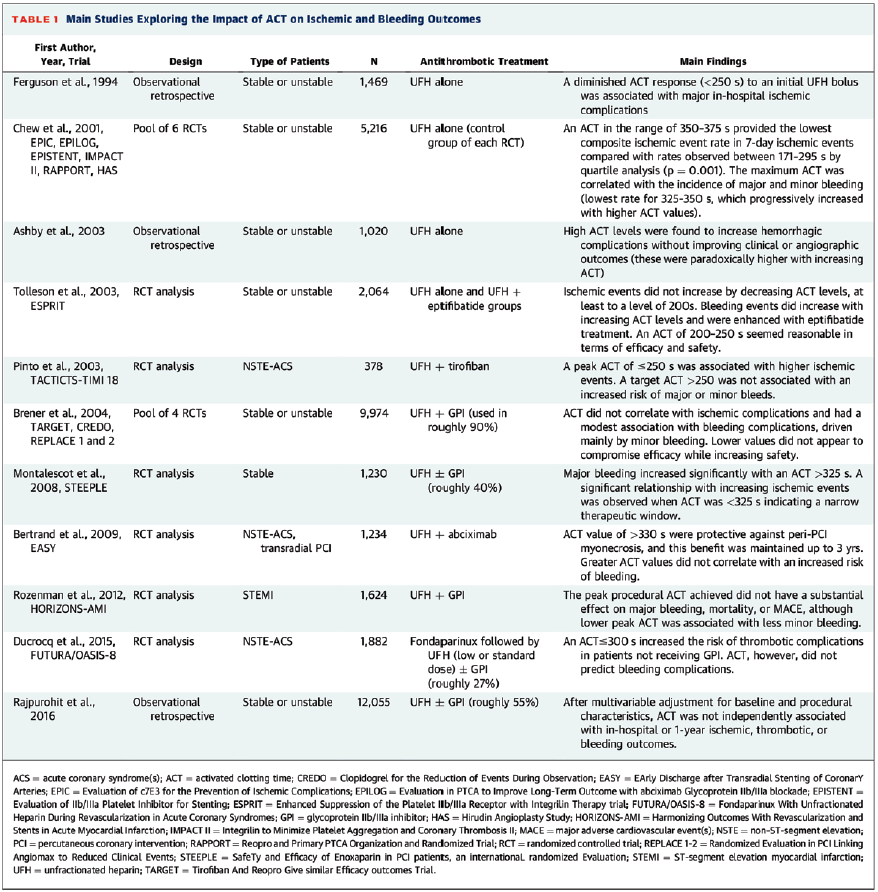

Reprinted with permission from Valgimigli M, Gargiulo G. Activated clotting time during unfractionated heparin-supported coronary intervention: is access site the new piece of the puzzle? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018 Jun 11; 11(11): 1046-1049. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2018.02.022.

Mike Ragosta, MD, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia: Good question. At the University of Virginia, for planned PCI cases, our practice has been to confirm first with the nurse that the patient has a reliable IV, administer the heparin, proceed with guide engagement, lesion wiring, and meanwhile, draw an ACT within a few minutes of administering heparin. We use a lot of cangrelor and that is administered simultaneously with the heparin. But we don’t wait for the ACT to start ballooning, etc. We don’t use much bivalirudin but if we do, we do the same thing and check the ACT just to be sure [the heparin] gets in.

Mike Ragosta, MD, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia: Good question. At the University of Virginia, for planned PCI cases, our practice has been to confirm first with the nurse that the patient has a reliable IV, administer the heparin, proceed with guide engagement, lesion wiring, and meanwhile, draw an ACT within a few minutes of administering heparin. We use a lot of cangrelor and that is administered simultaneously with the heparin. But we don’t wait for the ACT to start ballooning, etc. We don’t use much bivalirudin but if we do, we do the same thing and check the ACT just to be sure [the heparin] gets in.

When radial access and a diagnostic cath are done first, we check the ACT when swapping out for a guide and before we start an intervention; usually it is therapeutic.

Arnold Seto, MD, MPA, VA Long Beach, Long Beach, California: National and international guidelines recommend an unfractionated heparin (UFH) dose of 70-100 U/kg to achieve an ACT of 250-300s for supporting PCI, (>200s when glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors are used). Understanding variable responses to and potencies of UFH, along with the risk of infiltrated IVs, etc., ACT checks are strongly recommended in American guidelines but apparently are less frequently performed in Europe.

Arnold Seto, MD, MPA, VA Long Beach, Long Beach, California: National and international guidelines recommend an unfractionated heparin (UFH) dose of 70-100 U/kg to achieve an ACT of 250-300s for supporting PCI, (>200s when glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors are used). Understanding variable responses to and potencies of UFH, along with the risk of infiltrated IVs, etc., ACT checks are strongly recommended in American guidelines but apparently are less frequently performed in Europe.

Surprisingly, though, there have been no prospective coronary studies that have assessed the value of ACT-guided dosing compared with standard UFH dosing, probably because the difference might be too infrequent to detect, or no one feels comfortable randomizing patients to such a study. Thus, all of these recommendations regarding optimal ACT ranges are based on retrospective analysis of randomized data or registry data (Table). In a prospective study of 134 noncardiac cases, a 100 U/kg dose of UFH is sufficient to reach an ACT of >200s in 78% of patients and 41% reached >250s.1

I’ve noticed in reviewing cases both inside and outside the VA that ACTs are usually checked but not always returned prior to wiring the vessel or even starting the PCI. Undoubtedly the time required to return an ACT is a factor for busy operators, especially for the i-STAT machine, which has become prevalent in many labs. Result times average about 2-4 minutes. i-STAT device values were generally 43 seconds lower than Hemochron and 23 seconds lower than the Hepcon (Medtronic) devices. All devices correlated strongly with anti-factor Xa levels.2

Personally, I suspect that the anticoagulation requirement for wiring the vessel (i.e., for fractional flow reserve [FFR] only, or in preparation for PCI) is not an ACT >250s but probably lower, given the absence of disrupted endothelium and exposed tissue factor that would occur during angioplasty. As a result, in my practice, an ACT >200s where the normal ACT <120s is sufficient evidence of anticoagulation for me that (A) heparin has been effectively delivered and is working, and (B) it is safe for me to begin wiring a coronary artery for FFR or eventually for PCI while I give additional heparin to achieve ACT >250s. However, I will generally wait until the ACT is anticipated to be >250s from my additional dosing before I actually begin angioplasty and disrupting vessels, to avoid the risk of stent thrombosis.

Mort Kern, MD, VA Long Beach, Long Beach, California: I had not been paying close attention to this issue until Dr. Seto brought it up. Our cath lab manager showed us the VA policy recommendation of waiting to have the ACT verified in therapeutic range before starting PCI. I think this is a good idea. I also think that we should not be in a hurry to begin PCI when there is preventable risk of thrombosis by checking the ACT. Repeat after me: “Safety first, especially with PCI patients”. The balance of bleeding risk versus thrombosis depends on the type of procedure, concomitant medication, and patient-specific factors related to the patient’s hematologic responsiveness.

Mort Kern, MD, VA Long Beach, Long Beach, California: I had not been paying close attention to this issue until Dr. Seto brought it up. Our cath lab manager showed us the VA policy recommendation of waiting to have the ACT verified in therapeutic range before starting PCI. I think this is a good idea. I also think that we should not be in a hurry to begin PCI when there is preventable risk of thrombosis by checking the ACT. Repeat after me: “Safety first, especially with PCI patients”. The balance of bleeding risk versus thrombosis depends on the type of procedure, concomitant medication, and patient-specific factors related to the patient’s hematologic responsiveness.

When Should We Measure ACT After Bolus Dosing?

The ACT is measured approximately five to ten minutes after the initial heparin bolus, confirming we are working with a therapeutic dose. Based on the ACT, we can then adjust heparin dosage as needed. If the ACT measurement is subtherapeutic, additional boluses of UFH (e.g., 10-40 U/kg) can be administered. Our initial dose for both diagnostic and PCI cases is 5000u (about 70-100 U/kg after gaining arterial access to achieve adequate anticoagulation).

When Should We Re-Measure ACT?

Our practice is to remeasure about every 20-30 minutes, particularly for prolonged procedures. If there is evidence of a potential thrombotic complications (i.e., if a clot forms during the procedure), additional heparin is given to raise the ACT >250s.

Considerations For Altering the ACT Rules

For elective PCI cases, where potent antiplatelet agents like clopidogrel and aspirin are given beforehand, the initial ACT target can be lower. Higher bleeding risk occurs with the use of femoral access more than with the use of radial access. Higher ACT values are primarily associated with major bleeding in transfemoral PCI, but not in transradial PCI.

ACT Devices

The specific ACT device used can impact the ACT therapeutic range. For example, a Hemochron device will typically have a higher target range than a Hemotec or i-STAT device. Many of the established ACT cutoffs are based on older data from before the widespread use of modern stents and antiplatelet drugs. The Figure compares Hemochron and i-STAT ACT measurements at several time points before and after cardiac surgery.

Accurate ACT?

There are a few important considerations to ensure accurate ACT values. Operating teams should standardize ACT technique. Drawing from the arterial sheath side-arm versus the automated injector line can prevent large variations in the ACT results due to contamination of the sample. Avoid contamination of the blood sample when blood is drawn from an IV line that is used for heparin administration. The sample may have residual heparin, leading to a falsely elevated ACT.

Another source of ACT errors is sample mishandling. Do not let a heparinized blood sample sit for too long before testing. Platelet factor 4 (PF4) released from circulating platelets can neutralize the heparin and cause a falsely low ACT. Also recall that an ACT device can malfunction. Using an expired test cartridge can also cause ACT errors.

Lastly, because the ACT test is a global measure of whole blood coagulation, there are patient-specific conditions that can adversely affect the ACT such as hypothermia, thrombocytopenia or platelet dysfunction, or antithrombin III deficiency. Recall that since heparin binds to antithrombin III, a congenital or acquired deficiency of antithrombin can make a patient resistant to heparin and produce a falsely low ACT. Noteworthy, newer anticoagulant therapies are not accurately reflected by the ACT. This fact is particularly true for direct thrombin inhibitors (DTI), and an ACT test is not approved for monitoring these drugs.

The Bottom Line

The ACT should be in therapeutic range before disrupting a coronary artery. The rule is no guidewire insertion until ACT is in therapeutic range. While this rule applies as well to measuring FFR/nonhyperemic pressure ratio (NHPR), we often insert a pressure wire and measure FFR/NHPR to decide whether to proceed with PCI while awaiting the return of the ACT value. While not exactly the letter of the law, we try to ensure we have an ACT in range before starting the PCI part of the procedure. Rules are rules, and I think we should follow this one.

References

1. Doganer O, Roosendaal LC, Wiersema AM, et al. Weight based heparin dosage with activated clotting time monitoring leads to adequate and safe anticoagulation in non-cardiac arterial procedures. Ann Vasc Surg. 2022 Aug; 84: 327-335. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2022.01.029

2. Ojito JW, Hannan RL, Burgos MM, et al. Comparison of point-of-care activated clotting time systems utilized in a single pediatric institution. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2012 Mar; 44(1): 15-20. Accessed September 15, 2025. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4557434/pdf/ject-44-15.pdf

Sources/Recommended Reading

1. Chew DP, Bhatt DL, Lincoff AM, et al. Defining the optimal activated clotting time during percutaneous coronary intervention: aggregate results from 6 randomized, controlled trials. Circulation. 2001 Feb 20; 103(7): 961-966. doi:10.1161/01.cir.103.7.961

2. Ducrocq G, Jolly S, Mehta SR, et al. Activated clotting time and outcomes during percutaneous coronary intervention for non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: insights from the FUTURA/OASIS-8 Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015 Apr; 8(4): e002044. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.002044

3. Valgimigli M, Gargiulo G. Activated clotting time during unfractionated heparin-supported coronary intervention: is access site the new piece of the puzzle? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018 Jun 11; 11(11): 1046-1049. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2018.02.022

4. Heemelaar JC, Berkhout T, Heestermans AACM, et al. Measuring activated clotting time during cardiac catheterization and PCI: the effect of the sampling site. J Interv Cardiol. 2021 Sep 11; 2021: 4091289. doi:10.1155/2021/4091289

Morton J. Kern, MD, MSCAI, FACC, FAHA

Clinical Editor; Interventional Cardiologist, Long Beach VA Medical Center, Long Beach, California; Professor of Medicine, University of California, Irvine Medical Center, Orange, California

Disclosures: Dr. Morton Kern reports he is a consultant for Abiomed, Abbott Vascular, Philips, ACIST Medical, and Opsens Inc.

Dr. Kern can be contacted at mortonkern2007@gmail.com

On X @MortonKern

Find More:

Renal Denervation Topic Center

Cardiovascular Ambulatory Surgery Centers (ASCs) Topic Center

Grand Rounds With Morton Kern, MD

Peripheral Artery Disease Topic Center

Podcasts: Cath Lab Conversations