Could Door to Lactate Clearance (DLC) in Shock Be the New Door-to-Balloon Time of STEMI?

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Cath Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Morton J. Kern, MD, MSCAI, FACC, FAHA1

With contributions from Arnold H. Seto, MD, MPA, FSCAI, FACC2

1Clinical Editor; Interventional Cardiologist, Long Beach VA Medical Center, Long Beach, California; Professor of Medicine, University of California, Irvine Medical Center, Orange, California;

2Chief of Cardiology at the Long Beach VA Medical Center, Long Beach, California; Associate Clinical Professor and Director of Interventional Research, University of California, Irvine, California

Disclosures: Dr. Morton Kern reports he is a consultant for Abiomed, Abbott Vascular, Philips, ACIST Medical, and Opsens Inc.

Dr. Kern can be contacted at mortonkern2007@gmail.com.

Years ago, before I went to medical school and just after I graduated from UCLA, I worked in the Shock Research Lab at Hollywood Presbyterian Hospital in Los Angeles, run by a famous cardiologist, Dr. Max Harry Weil. He was known as the founder of the field of critical care medicine, and was the founder and chief of the Shock Research Lab. As a newbie technician, I was thrilled to be in what was a unique setting in all the medical world at that time. It was the first 2-bed intensive care unit (ICU) dedicated to the most critically ill patients in shock with early computerized systems to draw blood, and continuously monitor and record data inputs from all hemodynamic and laboratory measurements, body temperatures, urine output, respiratory functions, electrocardiogram (ECG) rhythms, etc. It was staffed 24/7 by cardiologist research fellows, technicians, and ICU nurses, and the ICU beds were adjacent to a chemistry and blood gas lab next door. This is where I first cultivated my love for cardiology and found stimulus from Dr. Weil to move on to medical school and emulate my mentors in this lab. The year was 1971 and I knew little about shock when I got there and much more when I left for medical school at the end of my first year of work. One thing I did take with me was that there was so much more to shock than mere low blood pressure, with often, but not always, the presence of elevated lactate.

Years ago, before I went to medical school and just after I graduated from UCLA, I worked in the Shock Research Lab at Hollywood Presbyterian Hospital in Los Angeles, run by a famous cardiologist, Dr. Max Harry Weil. He was known as the founder of the field of critical care medicine, and was the founder and chief of the Shock Research Lab. As a newbie technician, I was thrilled to be in what was a unique setting in all the medical world at that time. It was the first 2-bed intensive care unit (ICU) dedicated to the most critically ill patients in shock with early computerized systems to draw blood, and continuously monitor and record data inputs from all hemodynamic and laboratory measurements, body temperatures, urine output, respiratory functions, electrocardiogram (ECG) rhythms, etc. It was staffed 24/7 by cardiologist research fellows, technicians, and ICU nurses, and the ICU beds were adjacent to a chemistry and blood gas lab next door. This is where I first cultivated my love for cardiology and found stimulus from Dr. Weil to move on to medical school and emulate my mentors in this lab. The year was 1971 and I knew little about shock when I got there and much more when I left for medical school at the end of my first year of work. One thing I did take with me was that there was so much more to shock than mere low blood pressure, with often, but not always, the presence of elevated lactate.

Over the ensuing 50 years since I was first exposed to the management of the shock patient, the issues surrounding the pathophysiology, mechanisms, and metabolic derangements of shock have dramatically evolved, with each type of shock becoming a subspeciality of its own. Cardiogenic shock is clearly different than bacteremic, neurogenic, toxic, and traumatic (hypovolemic) shock. Significant research progress has been made just in arriving at a common language for shock, through the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) Stages of Shock.1,2 I was unaware that lactate3 has become a “cause célèbre” to current shock devotees, as noted by the recent publication of the SCAI Door to Lactate Clearance Cardiogenic Shock Initiative: Definition, Hypothesis, and Call to Action, headed by our current SCAI president, Dr. Srihari Naidu.4 I had paid little attention to lactate other than when treating our ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients in stages A-C, where an elevated lactate seemed to push my pace of treatment to a higher level of care sooner. Like many others, I didn’t worry too much about which way the lactate was trending as long as the patient was improving clinically. Based on this new shock Initiative though, I thought this page would be a good place to provide a recap and share some insights.

The Bottom Line Up Front

What did the SCAI DLC paper conclude? Presented at SCAI Shock 2025 summit, the clinical goal is to reduce or ‘clear’ lactate levels to <2 mmol/L within 24 hours of diagnosis of SCAI shock classification stage C/D/E.

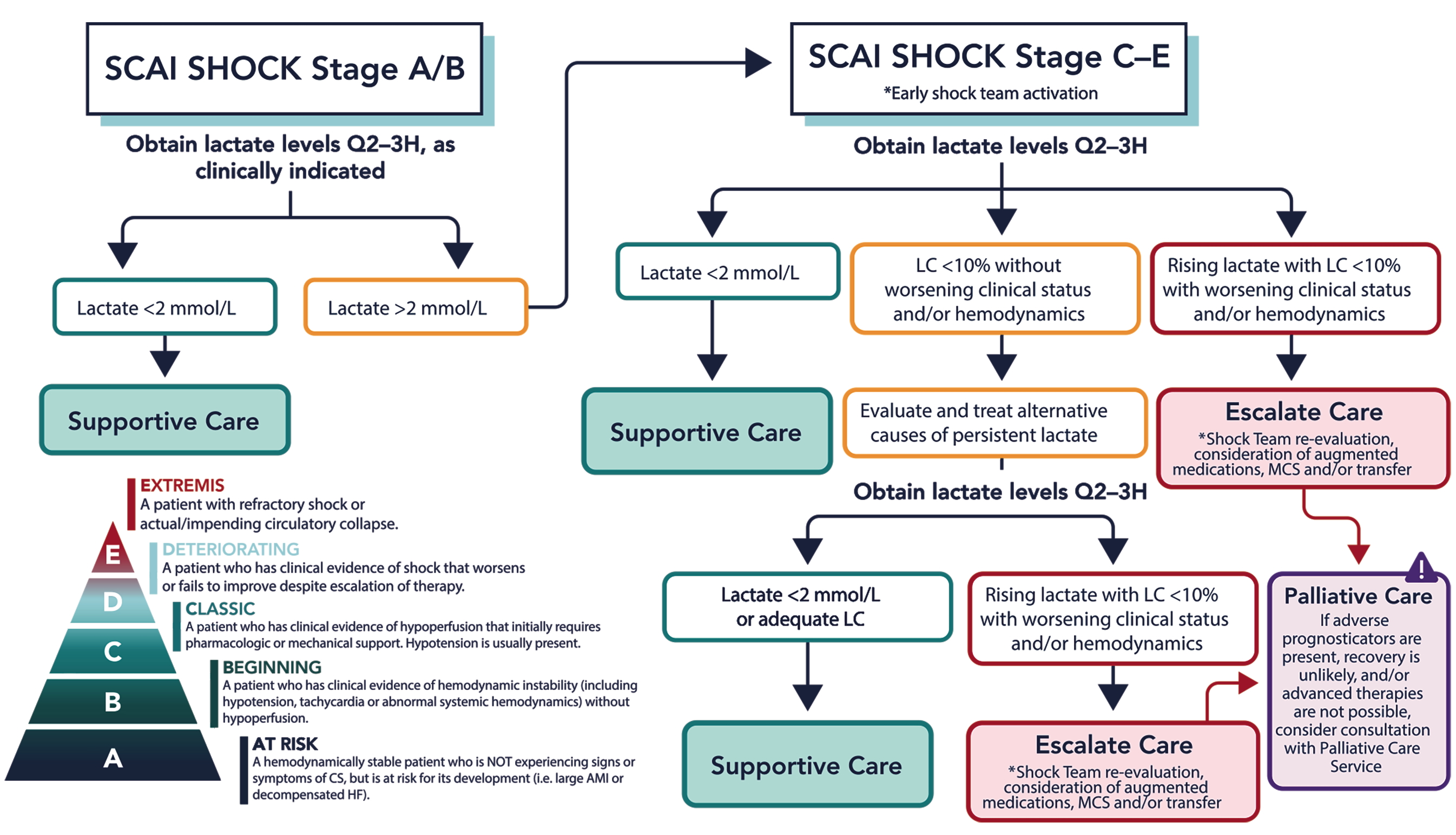

The document4 details the background and pathophysiology of lactate in cardiogenic shock, lactate elevation and clearance as marker of shock trajectory, care systems regarding use of lactate, literature review supporting the use of lactate for prognosis, and proposes a management strategy for incorporating lactate (both absolute and its trajectory) into practice. Naidu et al4 provide a flowchart for how door to lactate clearance may be incorporated into cardiogenic shock care (Figure). Based on the clinical course and lactate level, escalation of care would require reevaluation through additional imaging or invasive hemodynamics, and initiation of vasopressors, inotropes, mechanical circulatory support devices (MCS), cardiac intervention, or ultimately, initiating palliative care.

CS, cardiogenic shock; LC, lactate clearance; MCS, mechanical circulatory support; SCAI, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions.

Reprinted from Naidu SS, Nathan S, Basir MB, et al. SCAI Door to Lactate Clearance (SCAI DLC) Cardiogenic Shock Initiative: Definition, Hypothesis, and Call to Action. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2025 September 18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jscai.2025.103996

The Case for Lactate Clearance and Prognosis

The evidence base for lactate clearance comes from multiple randomized, controlled trials (provided on the tables in Naidu et al4) including IABP-SHOCK II,5 in which lactate levels at 8 hours were the strongest predictor of mortality among all variables analyzed; VA-ECLS,6 in which lactate clearance was associated with survival across a variety of disease states, including cardiac arrest, sepsis, and cardiogenic shock; and the DOREMI trial,7 in which complete clearance of lactate, percentage lactate clearance, and percentage lactate clearance per hour were all independent predictors of survival in a shock population.

However, some consider the strength of the evidence insufficient to produce the same urgency as the door-to-balloon protocol for STEMI that we are all familiar with. While mortality may be tied to lactate as a marker, the multifactorial presentations and co-morbidities of shock patients complicate the linkage of the exact time to lactate clearance to survival. Earlier lactate clearance is likely better or at least showing better potential for survival.

Dr. Naidu’s 3 Keys for the Shock Team’s Door-to-Lactate Clearance

- Accurately and efficiently diagnose cardiogenic shock. It starts with stage A, which includes all patients likely to spiral into shock/patients at risk of developing shock. Check the lactate and confirm it is normal, and thus stage A or B. If the lactate is borderline, repeat it within 2 hours.

- If the lactate is >2 mmol/L, indicating stage C or greater, initiate the shock team. Inform all allied members of the shock team of the situation. Include patients with lactate 1.5-1.9 mmol/L, which is stage B.

- Repeat the lactate every 2 to 3 hours to observe the effects of your interventions. Escalate treatments if lactate is not down-trending. If the lactate is decreasing, then perfusion is improved less tissue loss complications occurring, including better renal perfusion. If lactate is not improving, then escalation of MCS or transfer protocols should be initiated.

Dr. Seto’s Impressions

Dr. Seto’s Impressions

The call from SCAI’s President to study DLC as a potential quality improvement initiative is important for everyone in the community to consider. Similar to before “door-to-balloon” time goals became a quality measure to which our facilities were held accountable, there are delays in care delivery and escalation that probably contribute to excess mortality in shock patients. If “time is muscle” for STEMI, then time in uncorrected shock is brain, kidney, lung, and the rest of the body in cardiogenic shock.

We should all address shock as quickly as possible, and after improvement in blood pressure and heart rate, a Q2-3 hour lactate assessment makes sense to assess the adequacy of perfusion. A pulmonary artery catheter, if present, can also be useful. While not all cardiogenic shock can be successfully treated, the point of the document is that to improve shock outcomes we need to escalate care if what we are doing is not working (i.e., improving perfusion), or otherwise we need to consider palliative care and goals of care earlier.

As many community facilities do not have shock teams, transplant options, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), the major challenge becomes developing systems that are able to escalate care as needed. Should more facilities have Impella (Abiomed) or ECMO? Should patients with cardiac arrest bypass existing STEMI receiving centers and go to a regional shock center? These unanswered questions, as well as the absence of randomized evidence to date that DLC would save lives, are why DLC needs to be studied further as a goal.

The Bottom Line

Currently, it appears the writing group strongly promotes the study of DLC from a large real-world registry to validate the hypothesis. The SCAI also calls clinical investigators and registry organizers “to incorporate and evaluate serial lactate and DLC prospectively, to see whether this rather simple intervention translates to improved survival.”

References

- Baran DA, Grines CL, Bailey S, et al. SCAI clinical expert consensus statement on the classification of cardiogenic shock: this document was endorsed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) in April 2019. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019; 94(1): 29-37. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccd.28329

- Naidu SS, Baran DA, Jentzer JC, et al. SCAI SHOCK stage classification expert consensus update: a review and incorporation of validation studies. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2022; 1(1): 100008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jscai.2021.100008

- Henning RJ, Weil MH, Weiner F. Blood lactate as prognostic indicator of survival in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circ Shock. 1982; 9(3): 307-315.

- Naidu SS, Nathan S, Basir MB, et al. SCAI Door to Lactate Clearance (SCAI DLC) Cardiogenic Shock Initiative: Definition, Hypothesis, and Call to Action. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2025 September 18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jscai.2025.103996

- Fuernau G, Desch S, De Waha-Thiele S, et al. Arterial lactate in cardiogenic shock. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020 Oct 12; 13(19): 2208-2216. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2020.06.037

- Laimoud M, Machado P, Lo MG, et al. The absolute lactate levels versus clearance for prognostication of post-cardiotomy patients on veno-arterial ECMO. ESC Heart Fail. 2024; 11(6): 3511-3522. doi:10.1002/ehf2.14910

- Marbach JA, Di Santo P, Kapur NK, et al. Lactate clearance as a surrogate for mortality in cardiogenic shock: insights from the DOREMI trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022; 11(6): e023322. doi:10.1161/JAHA.121.023322

Find More:

Renal Denervation Topic Center

Cardiovascular Ambulatory Surgery Centers (ASCs) Topic Center

Grand Rounds With Morton Kern, MD

Peripheral Artery Disease Topic Center

Go to Cath Lab Digest's Current Issue

Go to the Journal of Invasive Cardiology Issue