Coronary Artery Fistulas: Unmasking Acquired Origins in the Setting of Chronic Coronary Artery Disease

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Cath Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Arnav Kumar Singla, MD; Cody Uhlich, MD; Namrata Kadambi, MD; Shannon Li, MD; Stuart Chen, MD; Fareed Moses Collado, MD

Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois

Disclosure: The authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

The authors can be contacted via Arnav Kumar Singla at arnav_k_singla@rush.edu.

Abstract

Objectives: Coronary artery fistulas (CAFs) are uncommon vascular anomalies traditionally considered congenital. However, emerging evidence suggests that chronic coronary artery disease (CAD) may trigger CAF formation through ischemia-induced angiogenesis. Two cases illustrate the potential relationship between CAD, angiogenic signaling, and CAF formation, while exploring the clinical implications of shunt anatomy and physiology.

Methods: Two cases of acquired CAFs were evaluated, each presenting with distinct symptoms. The first case involved a left anterior descending artery (LAD) to pulmonary artery (PA) CAF in a patient with dyspnea and ischemic cardiomyopathy. The second case described a right coronary artery (RCA) to PA and LAD to PA CAF, complicated by a giant coronary artery aneurysm, in a patient presenting with palpitations. In both cases, angiographic imaging and clinical data were analyzed to assess anatomical features and potential pathophysiological mechanisms.

Results: Patient A exhibited significant left-to-right shunting with pulmonary hypertension, severe mitral regurgitation, and reduced ejection fraction, requiring coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), mitral valve replacement, and CAF ligation. Patient B had dual CAFs with an associated coronary artery aneurysm, detected incidentally during evaluation for palpitations. The coronary artery aneurysm subsequently thrombosed, likely due to flow dynamics altered by CABG. Both cases demonstrated CAFs originating near areas of significant CAD and calcification, with angiographic findings suggestive of chronic ischemia-driven angiogenesis.

Conclusion: This case series underscores the potential for chronic CAD to induce CAF formation through VEGF-mediated angiogenesis, challenging the conventional assumption of congenital origin in adult presentations. Proximity to CAD-affected regions, shunt physiology, and associated symptoms should prompt clinicians to consider angiogenesis-related mechanisms when evaluating suspected CAFs. Further research is warranted to explore CAD-related angiogenic patterns and their implications for CAF diagnosis, management, and prognosis.

Background

Coronary artery fistulas (CAF) are rare anomalies with variable presentations and complications including congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, and arrhythmia depending on anatomy.1 Congenital etiologies account for the majority of CAFs, arising from the persistence of embryonic vascular sinusoids.1 The most common origin is the right coronary artery (RCA) (50%-55%) and left anterior descending artery (LAD) (35%-40%).2 Many CAFs are small and do not manifest clinically, and the true incidence is speculative. If symptomatic, serious complications can occur including infective endocarditis, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, arrhythmia, and death, necessitating improved understanding of both congenital and acquired etiologies.2

Although some reports suggest that a CAF may contribute to cardiomyopathy, it remains unclear whether anatomical variations influence the likelihood of symptomatic presentation.3 There is ample literature highlighting angiogenesis and development of collaterals as CAD progresses, but little discussing the relationship between stable, pre-existing CAD and/or calcification, and how this contributes to accelerated/aberrant neovascularization and CAF formation.4-6 Both cases discussed herein are significant examples of how this process may have occurred in patients previously unaffected by their underlying cardiac clinical picture. An emerging body of evidence suggests that chronic CAD may trigger CAF development through angiogenesis driven by ischemia-induced vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling. VEGF, particularly VEGF-A and VEGF-C, has been implicated in formation of collateral coronary circulation under ischemic conditions.7,8 In chronic CAD, prolonged ischemic stress and vascular inflammation promote aberrant angiogenesis, potentially culminating in CAF formation.9

We present two patients with distinct CAF presentations linked to chronic CAD and explore the angiogenic mechanisms underlying their formation. We aim to (1) describe the clinical presentation, anatomical characteristics, and shunt physiology in these cases; (2) investigate the potential role of CAD-driven angiogenesis in CAF formation; and (3) discuss the clinical implications of these findings for early detection and management of similar cases.6

Case Reports

Case #1

Patient A is a 71-year-old man, recreational marathoner, with a history of hyperlipidemia, prediabetes, and premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) and a strong family history of premature CAD. He presented with two months of dyspnea on exertion.

On physical examination, he did not have a murmur, elevated jugular venous pressure, or edema.

Initial diagnostic testing included a treadmill exercise stress electrocardiogram (ECG), during which he exercised for 9 minutes with the Bruce protocol without ischemic ECG changes. Resting ECG showed sinus bradycardia, prior anteroseptal infarct, left atrial abnormality, and PVCs. Chest x-ray revealed cardiomegaly and trace pleural effusion. Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated a markedly dilated left ventricular (LV) cavity, severely reduced systolic function with an ejection fraction (EF) of 15%-20%, diffuse hypokinesis, severe mitral regurgitation, dilated atria, and possible left-to-right interatrial shunt.

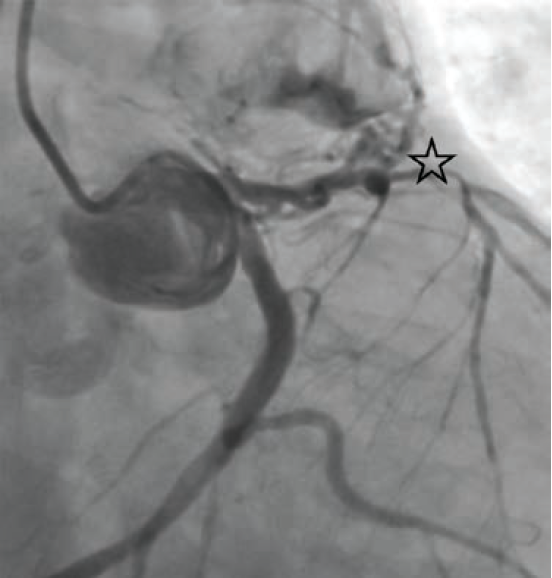

Subsequent left and right heart catheterization revealed a left-dominant coronary circulation, significant obstructive CAD involving the proximal LAD, and a fistula from the LAD to the main pulmonary artery with a pulmonary-to-systemic shunt ratio (Qp/Qs) of 1.3 (Figure 1). Right-sided filling pressures were normal, while pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) was moderately elevated. Cardiac index and cardiac output were preserved.

He underwent 2-vessel coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), fistula ligation, and bioprosthetic mitral valve replacement. His post-operative course was complicated by cardiogenic shock, requiring inotropic support and intra-aortic balloon pump placement, but he was successfully weaned after one week. He was discharged on guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Due to persistently reduced LV systolic function, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator was subsequently placed.

Case #2

Patient B is a 68-year-old man with a history of CAD who presented to his primary care physician with two years of palpitations and lightheadedness. His symptoms occurred at rest, lasted a few minutes, and resolved spontaneously. He exercises 3-4 times weekly and has a normal body mass index.

On physical examination, he had no murmur, jugular venous distension, or peripheral edema.

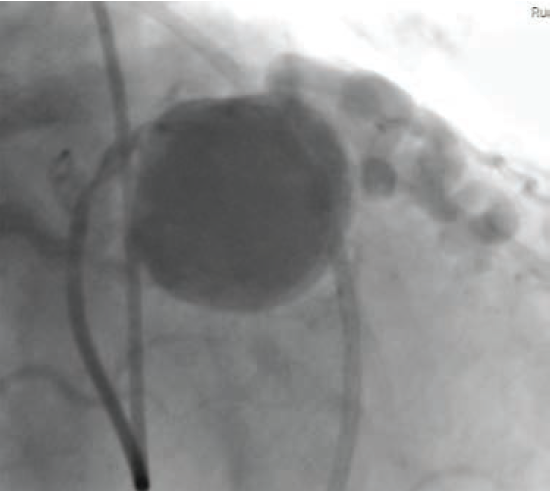

Initial diagnostic testing included a resting ECG which showed normal sinus rhythm. A coronary artery calcium computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, which could not exclude an incidental coronary artery aneurysm. He was referred for coronary CT angiography, which demonstrated 25%-49% stenosis at the ostium of the first diagonal branch from the proximal LAD, multiple stenoses in the distal LAD, mild-to-moderate diffuse calcification, and a giant 2.7 × 2.7 cm coronary artery aneurysm at the proximal LAD, proximal to a CAF between the LAD and right coronary artery (RCA).

Further testing included a 24-hour Holter monitor, treadmill exercise stress test, and transthoracic echocardiogram. The Holter monitor demonstrated 21 episodes of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). The transthoracic echocardiogram showed a preserved EF (60%-65%), a dilated right ventricle, and a large atrial septal aneurysm without evidence of shunting. The treadmill stress ECG was negative for ischemia, with the patient completing 9 minutes on the Bruce protocol without chest pain.

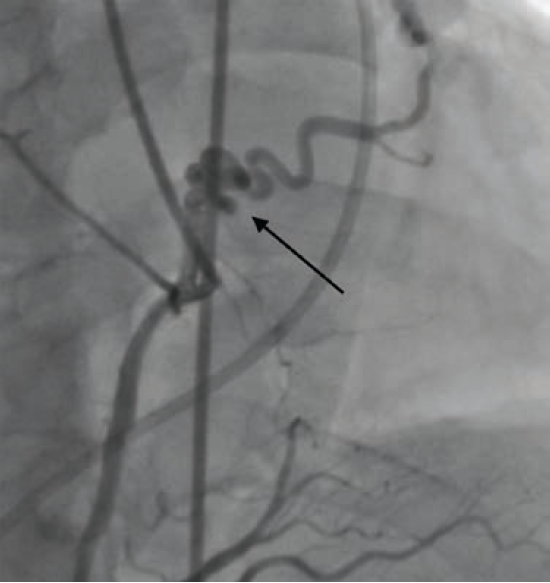

Cardiac catheterization revealed fistulae from the RCA to the pulmonary artery (PA) (Figure 2) and from the LAD to the PA, diffuse CAD, and a giant coronary artery aneurysm as previously described (Figure 3). The aneurysm demonstrated complex web-like vasculature extending towards the aortic root, across the right ventricular outflow tract, and into the proximal PA, with one large vessel connecting with the proximal RCA. The pulmonary-to-systemic flow ratio (Qp/Qs) was 1.14, indicating insignificant shunting, and cardiac index was normal.

The patient underwent ablation of SVT, suspected to be atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT), without complication. He subsequently underwent 3-vessel CABG to address his CAD and repair the RCA-to-PA CAF. Post-operatively, he developed atrial flutter, which resolved with cardioversion. He was discharged on amiodarone and warfarin, which were later discontinued after repeat Holter monitoring confirmed normal sinus rhythm.

He was scheduled for catheter-based closure of the coronary artery aneurysm; however, at the time of intervention, the aneurysm was suspected to have thrombosed due to competing flow following bypass graft surgery. Ascertained on fluoroscopy during left heart catheterization, the RCA-to-PA CAF demonstrated limited flow, while the LAD-to-PA CAF demonstrated partial flow. Repeat CCTA confirmed thrombosis of the coronary artery aneurysm without residual communication to the PA. The patient reported improved exercise capacity and no further cardiopulmonary symptoms.

Discussion

CAF is a rare, abnormal communication between a coronary artery and a cardiac chamber or the systemic or pulmonary circulation.1,2,10 Approximately 90% of CAF are congenital, presenting with symptoms of congestive heart failure near birth or remaining asymptomatic until adulthood.1,2 CAF are thought to occur due to persistence of embryonic sinusoids perfusing the myocardium or connections between coronaries and other mediastinal vessels.1,2,11 While acquired cases are typically provoked by percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, myocardial infarction, trauma, or irradiation, our patients had no history that suggested iatrogenic or traumatic development of their fistulae, raising questions regarding the underlying mechanisms of formation.1,2,12 CAF can occur spontaneously due to inflammatory pathologies such as endocarditis, CAD, and vasculitis.11,12

Coronary angiogenesis, mediated in part by VEGF and hypoxia-inducible factors, compensates for ischemia in conditions such as CAD.12-14 While this process may reduce oxidative stress and support tissue perfusion, dysregulated or excessive angiogenic activity has been linked to aberrant vascular connections.7-9, 12-14 These mechanisms provide a plausible explanation for the CAFs observed in our patients.

Both of our patients had significant CAD at presentation. In both cases, CAFs were located adjacent to areas of chronic CAD and calcification in the LAD, with angiographic findings suggestive of ischemia-induced neovascularization. As inflammation is known to drive angiogenesis and collateral vessel formation in settings such as infection and vasculitis, it is plausible that chronic, stable CAD may similarly contribute to CAF formation through inflammatory pathways. This association may be particularly relevant in patients presenting with new-onset heart failure or unexplained coronary abnormalities.

Early identification of CAFs may facilitate prompt intervention to mitigate complications such as aneurysm formation, pulmonary hypertension, or ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Patient A presented with dyspnea on exertion; his workup revealed a LAD-to-PA CAF with significant left-to-right shunt, mitral regurgitation, and elevated PCWP. Pulmonary artery systolic pressure was 46 mmHg, consistent with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH).15,16 This patient’s PAH is likely Group 1/Group 2, with one being the regurgitation of blood from the LV into the pulmonary vasculature and the second being the shunt physiology via the CAF, resulting in dyspnea on exertion, classically associated with this presentation.15 With surgical ligation of Patient A’s CAF, bypass graft surgery, and mitral valve replacement, his dyspnea improved. His ECG demonstrated a prior anteroseptal infarct, indicating a possible missed or silent myocardial infarction. The consequences of a missed myocardial infarction include Patient A’s worsening ischemic cardiomyopathy and reduced EF. Causes of CAF include myocardial infarction, which was discovered during his workup.12,17 While Patient A’s dyspnea on exertion can be explained by his ischemic cardiomyopathy and valvular pathology, the significant shunting due to his CAF can exacerbate symptom progression.17

Patient B’s palpitations were later discovered to be AVNRT. His workup revealed two fistulae to the PA complicated by a coronary artery aneurysm.18 He had no known history of inflammatory conditions such as Kawasaki disease or Takayasu arteritis that could explain his CAF or the coronary artery aneurysm.19,20 While Patient B’s shunting was less significant than that of Patient A, the cause of his palpitations warrants investigation. A coronary artery aneurysm has a higher risk of co-occurring with CAF and is typically due to CAD. While typically being asymptomatic, depending on the size, location, and compression upon adjacent structures, a coronary artery aneurysm can cause angina, tamponade, arrhythmia, and sudden cardiac death.18 Although Patient B’s symptoms resolved after ablation, his case highlights that tachyarrhythmias can be associated with underlying structural heart disease.

Conclusion

While previously thought to be primarily congenital, there is growing literature and presentations of CAF which may indicate acquired, spontaneous causes such as chronic inflammation due to CAD. These two cases highlight instances of CAFs associated with chronic CAD, suggesting that ischemia-induced angiogenesis may have contributed to acquired CAF formation. The pathophysiological link between chronic myocardial ischemia and aberrant vascular connections, potentially mediated by VEGF signaling, aligns with findings from animal and clinical studies.7-9 These cases underscore the importance of early evaluation and risk assessment of cardiac symptoms that may be attributable to CAF. Patients may tolerate a CAF for years until they result in complications that manifest symptoms such as dyspnea and palpitations. Although comorbidities such as CAD and valvular pathology can significantly contribute to clinical presentation, the potential impact of CAF should not be overlooked, particularly in the presence of concerning shunt physiology or aneurysmal anatomy.

CAD-induced CAF may be more prevalent than currently appreciated. As imaging modalities for detection improve, we may discover that CAD and acquired CAF are not necessarily mutually exclusive; one may portend the other. Further research is needed to clarify whether CAD-induced angiogenesis constitutes a distinct subtype of acquired CAF and to explore the potential role of angiogenic biomarkers such as VEGF in screening and risk stratification.

References

1. Vavuranakis M, Bush CA, Boudoulas H. Coronary artery fistulas in adults: incidence, angiographic characteristics, natural history. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1995 Jun; 35(2): 116-120. doi:10.1002/ccd.1810350207

2. Yun G, Nam TH, Chun EJ. Coronary artery fistulas: pathophysiology, imaging findings, and management. Radiographics. 2018 May-Jun; 38(3): 688-703. doi:10.1148/rg.2018170158.

3. Pérez Mijenes D, Lobo M, Gil JC, Vaz JA. Coronary artery fistula as another cause of acute heart failure. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2023 Sep 6; 10(10): 004053. doi:10.12890/2023_004053

4. Cheng R, Kransdorf EP, Wei J, et al. Angiogenesis on coronary angiography is a marker for accelerated cardiac allograft vasculopathy as assessed by intravascular ultrasound. Clin Transplant. 2017 Nov; 31(11). doi:10.1111/ctr.13069

5. Shah AH, Cusimano RJ, Ouzounian M. Coronary fistula and myocardial ischemia: what is the relationship? J Invasive Cardiol. 2016 Nov; 28(11):E134-E135. Accessed September 12, 2025. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/jic/articles/coronary-fistula-and-myocardial-ischemia-what-relationship

6. Balakrishnan S, Senthil Kumar B. Factors causing variability in formation of coronary collaterals during coronary artery disease. Folia Morphol (Warsz). 2022; 81(4): 815-824. doi:10.5603/FM.a2021.0110

7. Pätilä T. Myoblast transplantation and adenoviral VEGF-C transfer in porcine model of coronary artery disease. Academic dissertation: University of Helsinki. 2009. Accessed September 12, 2025. https://helda.helsinki.fi/server/api/core/bitstreams/d3b6f052-5006-4f30-8868-dbf40e4cf06f/content

8. Lin J, Jiang J, Zhou R, Li X, Ye J. MicroRNA-451b participates in coronary heart disease by targeting VEGFA. Open Med (Wars). 2019 Dec 26; 15: 1-7. doi:10.1515/med-2020-0001

9. Chistiakov DA, Melnichenko AA, Myasoedova VA, et al. Thrombospondins: a role in cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Jul 17; 18(7): 1540. doi:10.3390/ijms18071540

10. Dodge-Khatami A, Mavroudis C, Backer CL. Congenital heart surgery nomenclature and database project: anomalies of the coronary arteries. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000 Apr; 69(4 Suppl): S270-S297. doi:10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01248-5

11. Luo L, Kebede S, Wu S, Stouffer GA. Coronary artery fistulae. Am J Med Sci. 2006 Aug; 332(2): 79-84. doi:10.1097/00000441-200608000-00005

12. Said SA, Schiphorst RH, Derksen R, Wagenaar LJ. Coronary-cameral fistulas in adults: Acquired types (second of two parts). World J Cardiol. 2013 Dec 26; 5(12): 484-494. doi:10.4330/wjc.v5.i12.484

13. Zhou Y, Zhu X, Cui H, et al. The role of the VEGF family in coronary heart disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021 Aug 24; 8: 738325. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.738325

14. Braile M, Marcella S, Cristinziano L, et al. VEGF-A in cardiomyocytes and heart diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jul 26; 21(15): 5294. doi:10.3390/ijms21155294

15. Hoeper MM, Ghofrani HA, Grünig E, et al. Pulmonary hypertension. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017 Feb 3; 114(5): 73-84. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2017.0073

16. Oldroyd SH, Manek G, Sankari A, et al. Pulmonary hypertension. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Accessed September 12, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482463/

17. Rao SS, Agasthi P. Coronary artery fistula. [Updated 2023 Jun 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Accessed September 12, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559191/

18. Crawley PD, Mahlow WJ, Huntsinger DR, et al. Giant coronary artery aneurysms: review and update. Tex Heart Inst J. 2014 Dec 1; 41(6): 603-608. doi:10.14503/THIJ-13-3896

19. Owens AM, Plewa MC. Kawasaki Disease. [Updated 2023 Jun 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Accessed September 12, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537163/

20. Trinidad B, Surmachevska N, Lala V. Takayasu Arteritis. [Updated 2023 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Accessed September 12, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459127/