Successful Coil Embolization of Bleeding Facial Artery in a Patient With Facial Trauma

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Cath Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Mehmet Cilingiroglu, MD, FSCAI, FACC, FESC, FAHA1; Ibrahim Halil Inanc, MD, FSCAI, FACC, FESC2

1UT Houston MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas; 2Phoenixville Hospital Tower Health, Pennsylvania

The authors can be contacted via Dr. Mehmet Cirlingiroglu at dr.mehmetcilingiroglu@gmail.com.

Click here for a PDF of this article. Logging in or registration may be required (it's free!).

Abstract

Maxillofacial trauma can result in life-threatening hemorrhage from the external carotid artery and its branches. When non-invasive measures fail to control bleeding, surgical ligation is traditionally performed. However, access to a trauma surgeon may not always be available.

We present the case of a 35-year-old male who sustained severe facial trauma following a rollover motor vehicle accident. Despite initial non-invasive stabilization efforts, persistent hemorrhage from the facial artery necessitated urgent intervention. In the absence of a trauma surgeon on site, the patient was taken to the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Transcatheter embolization of the facial artery was successfully performed using the coil scaffolding technique, achieving hemostasis and enabling safe transfer to a higher-level trauma center.

Transcatheter embolization is a safe and effective alternative to surgical ligation, offering key advantages such as wider accessibility, rapid intervention, and avoidance of general anesthesia. This case highlights the importance of considering transcatheter embolization for hemorrhage control following maxillofacial trauma, particularly in resource-limited settings where surgical delays may increase morbidity and mortality.

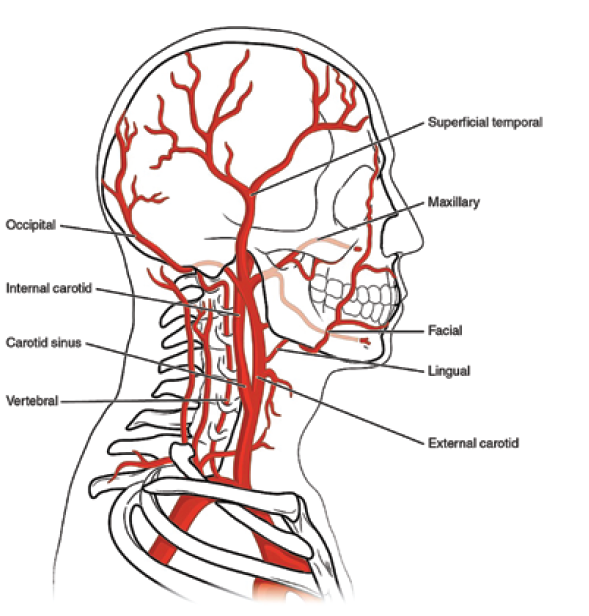

Maxillofacial injury is common following major facial trauma, and can lead to life-threatening hemorrhage. The branches of the external carotid artery (Figure 1) are most vulnerable to trauma as the vessels transverse bone structures.

Reprinted from WisTech Open. Accessed November 14, 2025. CC BY 2.0. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/anatphys/chapter/11-5-blood-vessels/

The facial, superficial temporal and terminal branches of the internal maxillary artery are most commonly affected.1 Rapid diagnosis and control of bleeding are essential to improve outcomes. Initial stabilization may be obtained by compression, packing, and correction of coagulopathy, but frequently, invasive treatment is ultimately required. Traditionally, surgical control is pursued, but transcatheter embolization offers an alternative, especially in settings where a trauma surgeon may not be available.2

We present a case of facial artery hemorrhage in a rural setting controlled by coil embolization, along with its clinical and radiological findings and management.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old male presented to a rural emergency room with facial trauma and major hemorrhage following a severe rollover motor vehicle accident. Non-invasive methods were unable to control facial bleeding as he was being prepared for transfer to a trauma center. Given the absence of a trauma surgeon in the face of hemodynamic instability, the decision was made to take him to the cardiac catheterization lab for angiographic evaluation and potential intervention.

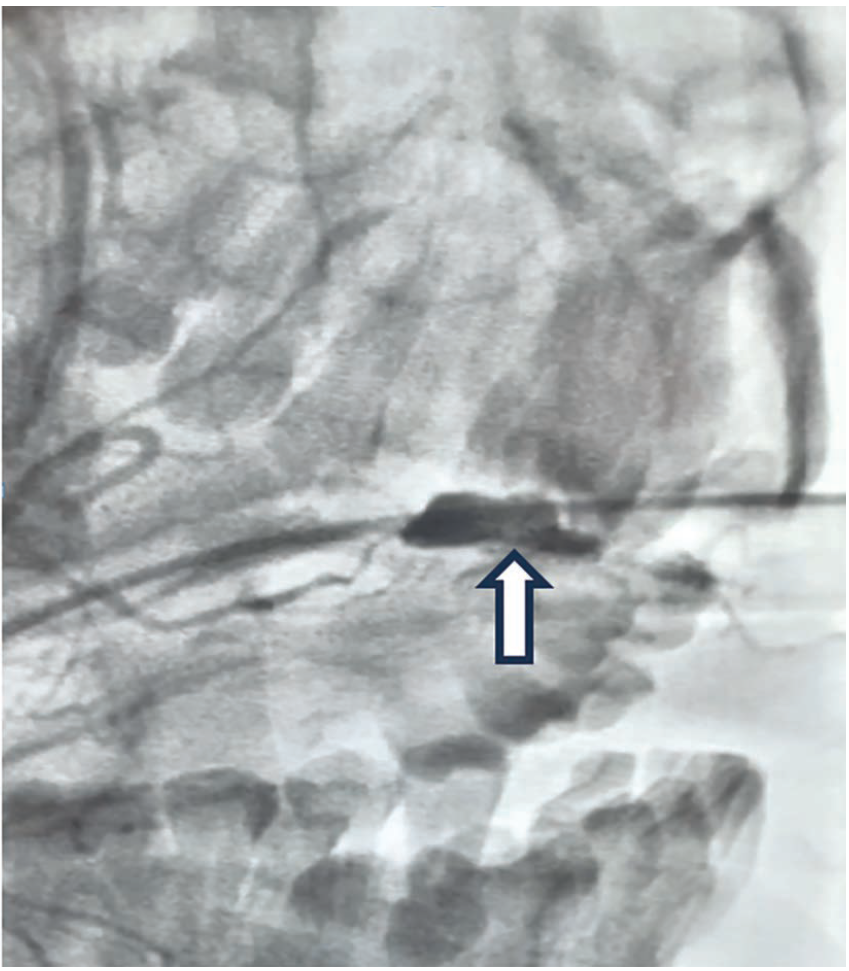

Baseline angiography demonstrated major bleeding from the main branch of the facial artery prior to bifurcation (Figure 2).

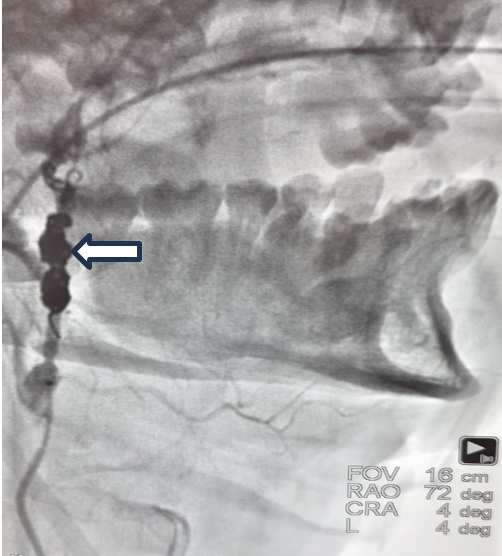

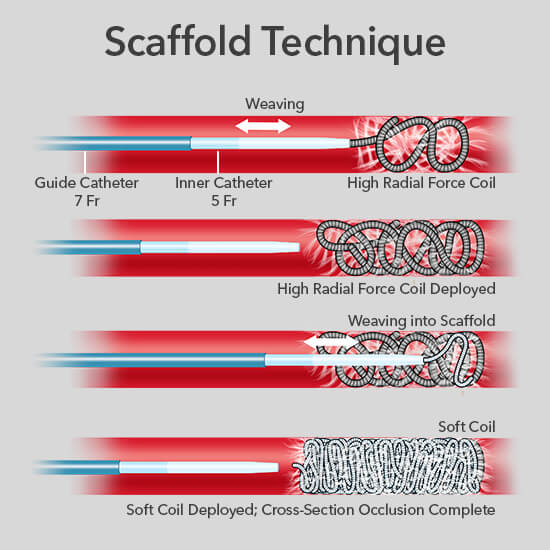

Using a 7 French (Fr) guide catheter and a 5 Fr inner catheter, high radial force coils were deployed and woven into a scaffold, acting as a thrombogenic focus. Complete cross-sectional occlusion was then obtained by deployment of soft coils, successfully achieving hemostasis (Figure 3, Video).

Video

The scaffolding technique (Figure 4) was preferred over other liquid embolization agents for endovascular embolization due to its convenience and readiness, ensuring valuable time savings in an emergency. Post procedure, the patient remained hemodynamically stable and was safely transferred for further trauma management at a higher-level care center.

Discussion

Maxillofacial trauma is present in up to 20% of all trauma cases and may lead to life-threatening hemorrhage from the external carotid artery and its branches. Traditionally open surgical ligation was preferred, but due to its many advantages, transcatheter embolization is emerging as an equally effective and safe alternative.2

A systematic review of 202 cases by Langel et al demonstrated that transcatheter embolization is as effective as surgery, achieving external carotid artery hemostasis with an efficacy of 79.4% to 100%.3 Liao et al showed significant correlation between successful transcatheter embolization hemostasis and patient survival.4 The advantages of transcatheter embolization include wider accessibility, faster procedure times, avoidance of general anesthesia, more precise hemorrhage localization, selective occlusion of multiple vessels not amenable to surgical repair, and concurrent embolization across systemic circulation.5 Furthermore, surgical ligation of maxillofacial vessels frequently requires either repeat ligation or subsequent transcatheter embolization.6

The principles of transcatheter embolization are well established in the non-trauma setting for a number of vascular lesions. Vascular access is established via the modified Seldinger technique using micropuncture, and then diagnostic angiography is performed to gain an overview of the at-risk circulation and identify the source of hemorrhage. The target vessel is occluded by feeding an embolic agent. Embolization is targeted as close to the lesion as possible to preserve proximal branches, with both distal and proximal occlusion preferred to prevent collateral rebleeding. The embolic agent is administered under fluoroscopic guidance until contrast medium stasis confirms successful vessel occlusion.7

A number of embolization agents are available with differing properties, each suited to varying vessel caliber and situations. The two most used in facial trauma are coils and gelatin foam (Gelfoam [Pfizer]).3 Platinum or steel coils promote rapid vessel occlusion within minutes by serving as a thrombogenic focus and causing endothelial injury to induce and thrombogenic factor release. The coils require no manual preparation and are available in various sizes. Potential complications with the use of coils include vessel injury, prevention of future distal access, coil migration, and infection. Gelfoam induces a foreign body reaction and necrotizing arteritis, providing temporary occlusion for weeks to months. However, its manual preparation and air bubble formation with contrast medium reduce reproducibility and increase the risk of aerobic infection. The combined use of both agents has shown effectiveness, particularly in coagulopathic patients. Other less commonly utilized embolic agents in trauma include polyvinyl alcohol, microspheres, n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA) glue, the Onyx liquid embolic system (Medtronic), and precipitating hydrophobic injectable liquid (PHIL) (Boston Scientific).8,9 Further research is needed to compare the safety and efficacy of embolic agents in both trauma and non-trauma settings. As advancements continue, novel agents like microparticles and biodegradable options are likely to enter clinical practice.10

All procedures carry some risk of complications. Major complications of transcatheter maxillofacial artery embolization include cerebrovascular events, facial nerve paralysis, cheek necrosis, and catheter entrapment, with reported rates of 2-4% (which may be falsely low due to publication bias). Minor complications, such as groin injury, trismus, palate ulceration, and persistent pain, occur in 10-25% of cases. However, with micro catheter use, operator experience, and improvement in equipment design, complication rates have been observed to improve.3

This case underscores the necessity for adaptability in emergency settings, where interventional techniques can play a life-saving role. Transcatheter embolization of the facial artery was successfully performed in a rural setting using the coil scaffolding technique for uncontrolled major bleeding following trauma. The patient was successfully stabilized and subsequently safely transferred to a higher level of care. We were unable to follow the patient for major or minor complications resulting from the procedure, although the risk is relatively low.

Transcatheter embolization is a safe and effective alternative to surgery, and already well-established in the non-trauma setting. We recommend considering transcatheter embolization in the setting of hemorrhage secondary to maxillofacial trauma, especially in a resource-limited setting where a trauma surgeon is not available, and delay is likely to result in morbidity and mortality.

Conclusion

This case highlights the critical role of transcatheter embolization in the management of life-threatening hemorrhage following maxillofacial trauma, particularly in resource-limited settings. The successful use of coil embolization in a rural emergency setting underscores the adaptability and effectiveness of endovascular techniques in achieving rapid hemostasis when surgical intervention is not immediately available. Transcatheter embolization provides a safe and effective alternative to traditional surgical methods, offering advantages such as broader accessibility, faster intervention, and the avoidance of general anesthesia.

References

1. Bernath MM, Mathew S, Kovoor J. Craniofacial trauma and vascular injury. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2021 Mar; 38(1): 45-52. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1724012

2. Vellimana AK, Lavie J, Chatterjee AR. Endovascular considerations in traumatic injury of the carotid and vertebral arteries. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2021 Mar; 38(1): 53-63. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1724008

3. Langel C, Lovric D, Zabret U, et al. Transarterial embolization of the external carotid artery in the treatment of life-threatening haemorrhage following blunt maxillofacial trauma. Radiol Oncol. 2020 May 28; 54(3): 253-262. doi:10.2478/raon-2020-0035

4. Liao CC, Hsu YP, Chen CT, Tseng YY. Transarterial embolization for intractable oronasal hemorrhage associated with craniofacial trauma: evaluation of prognostic factors. J Trauma. 2007; 63: 827-830. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31814b9466

5. Ghasemi Gorji M, Karbakhsh Ravari F, Rafiei A. Endovascular embolization for traumatic facial artery pseudoaneurysm: a case report. Cureus. 2024 Oct 25; 16(10): e72349. doi:10.7759/cureus.72349

6. Ray HM, Kuban JD, Tam AL, et al. Percutaneous retrograde left external carotid artery coil embolization for management of hemorrhage from a persistent proatlantal intersegmental artery type 2. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech. 2020 May 28; 6(2): 250-253. doi:10.1016/j.jvscit.2020.02.015

7. Ierardi AM, Piacentino F, Pesapane F, et al. Basic embolization techniques: tips and tricks. Acta Biomed. 2020 Jul 13; 91(8-S): 71-80. doi:10.23750/abm.v91i8-S.9974

8. Hörer TM, Ierardi AM, Carriero S, et al. Emergent vessel embolization for major traumatic and non-traumatic hemorrhage: Indications, tools and outcomes. Semin Vasc Surg. 2023 Jun; 36(2): 283-299. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2023.04.011

9. Perri P, Sena G, Piro P, et al. Onyx™ gel or coil versus hydrogel as embolic agents in endovascular applications: review of the literature and case series. Gels. 2024 May 2; 10(5): 312. doi:10.3390/gels10050312

10. Lee S, Ghosh A, Xiao N, et al. Embolic agents: particles. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2023 Jul 20; 40(3): 315-322. doi:10.1055/s-0043-1769744

11. How it Works. Scaffold technique. Cook Medical. https://www.cookmedical.com/interventional-radiology/coils-home/how-it-works/. Accessed November 26, 2025.

Find More:

Renal Denervation Topic Center

Cardiovascular Ambulatory Surgery Centers (ASCs) Topic Center

Grand Rounds With Morton Kern, MD

Peripheral Artery Disease Topic Center