Percutaneous Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD) Closure in a Postinfarct VSD: Better Lucky Than Good!

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Cath Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Neeraj Shah, MD, MPH1; Dennis Phillips, DO2; Hiroyuki Tsukui, MD3; Mitsugu Ogawa, MD3; Fouad Jabbour, MD1; Ashwin Thiagarajasubramanian, MD4; Juan Chahin, MD1

1Department of Interventional Cardiology; 2Department of Cardiac Anesthesiology; 3Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery Independence Health System Westmoreland Hospital, Greensburg, Pennsylvania; 4Department of Cardiology, Independence Health System Latrobe Hospital, Latrobe, Pennsylvania

Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

The authors can be contacted via Neeraj Shah, MD MPH, at neeraj.shah@independence.health.

X: @NeerajShahMD

Click here for a PDF of this article. Logging in or registration may be required (it's free!).

Postinfarct (PI) ventricular septal defect (VSD) usually occurs 2-7 days after untreated acute myocardial infarction (MI)1 due to interventricular septal rupture after necrosis. In the current era of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), PI VSD is a rare mechanical complication of MI with an incidence of 0.2-0.3%.2

The prognosis of an untreated PI VSD is extremely poor, with a mortality rate >90%. Even in the contemporary era with mechanical circulatory support devices (eg, Impella [Abiomed]), the 30-day mortality after PI VSD is almost 50% despite the presence of hemodynamic support during percutaneous or surgical closure.3 We present an uncommon case of post-MI VSD (of unknown duration) presenting with heart failure and subsequently treated with percutaneous closure.

Case Description

History and presentation. Our patient was a 69-year-old male who had prior history of resuscitated ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest in December 2007. At that time, the electrocardiogram (EKG) and transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) were normal. Cardiac catheterization showed multivessel coronary artery disease (CAD) including left main stenosis (Supplementary Figure 1). He underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) with left internal mammary artery to left anterior descending (LIMA to LAD) and right internal mammary artery to left circumflex (RIMA to LCx) obtuse marginal (OM3) branch. He refused an implantable cardioverter defibrillator and was lost to follow-up after May 2008.

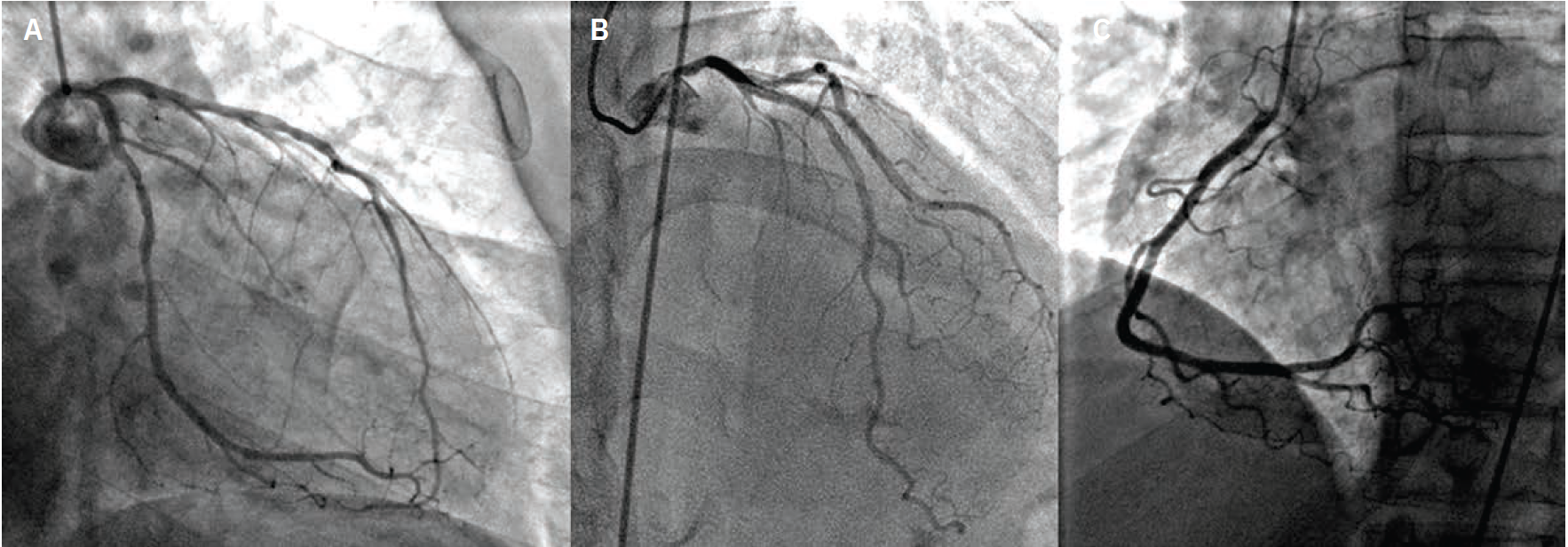

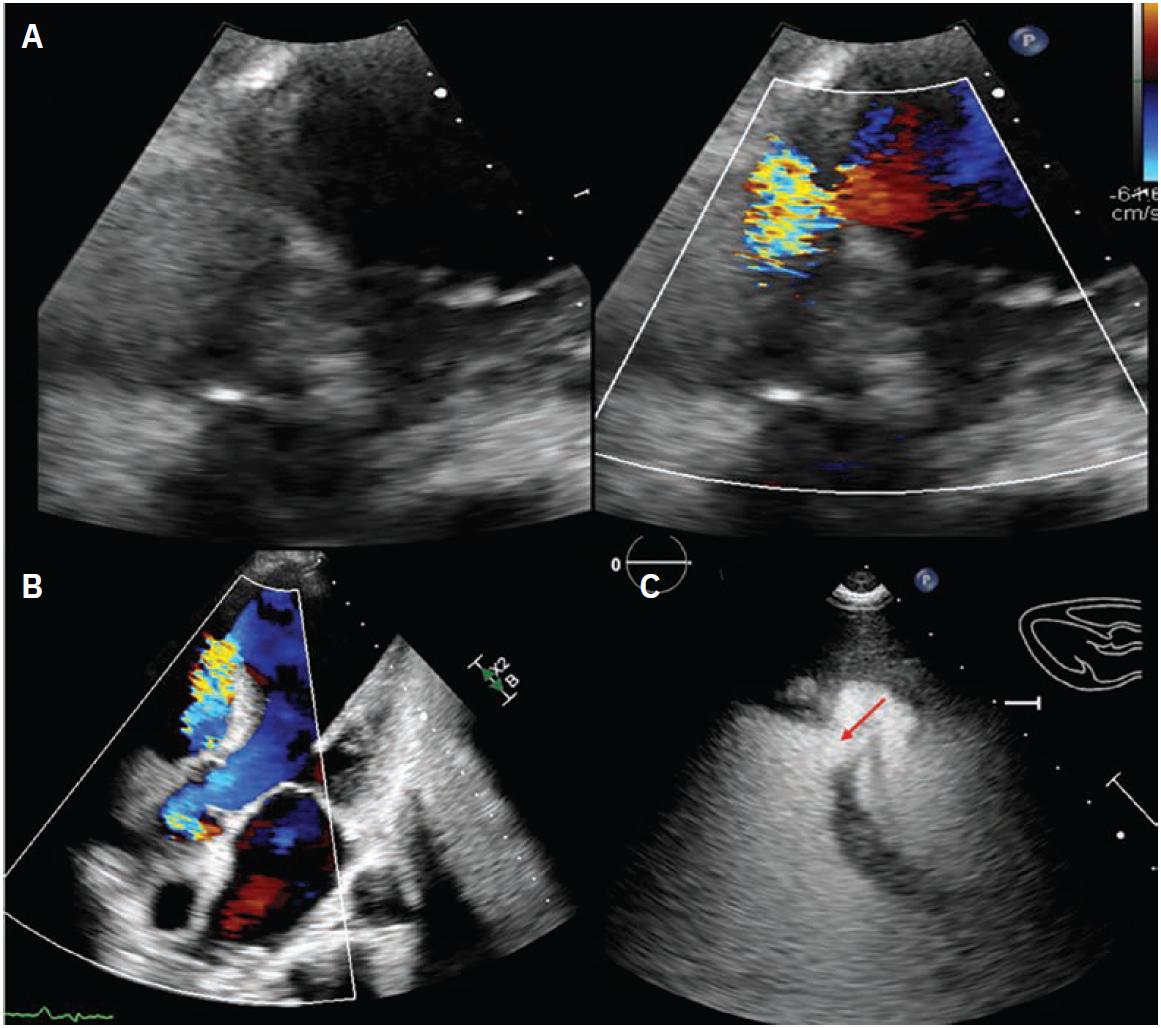

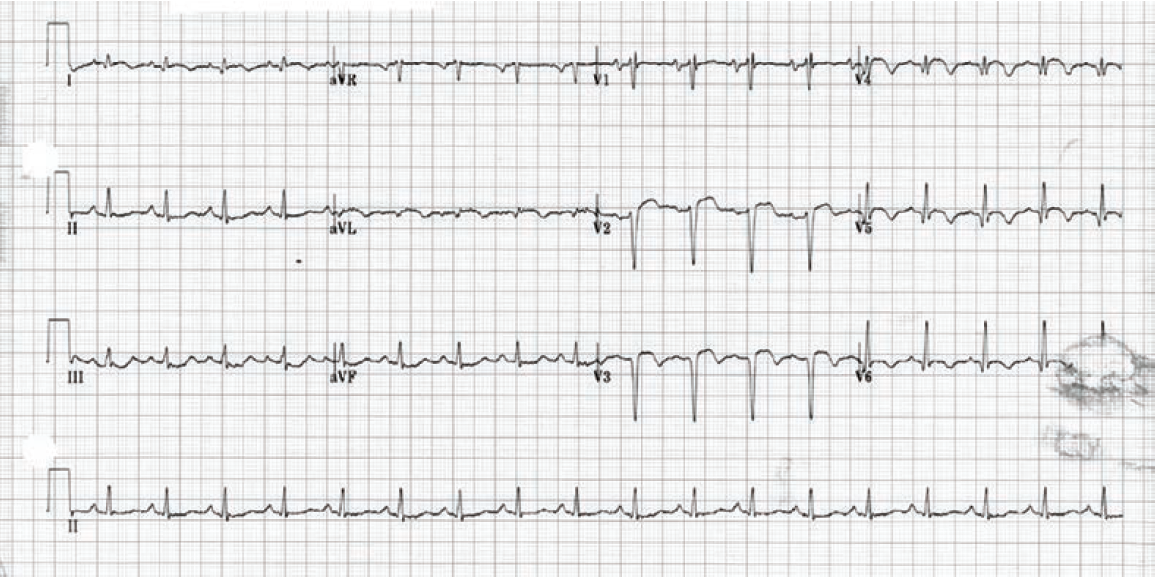

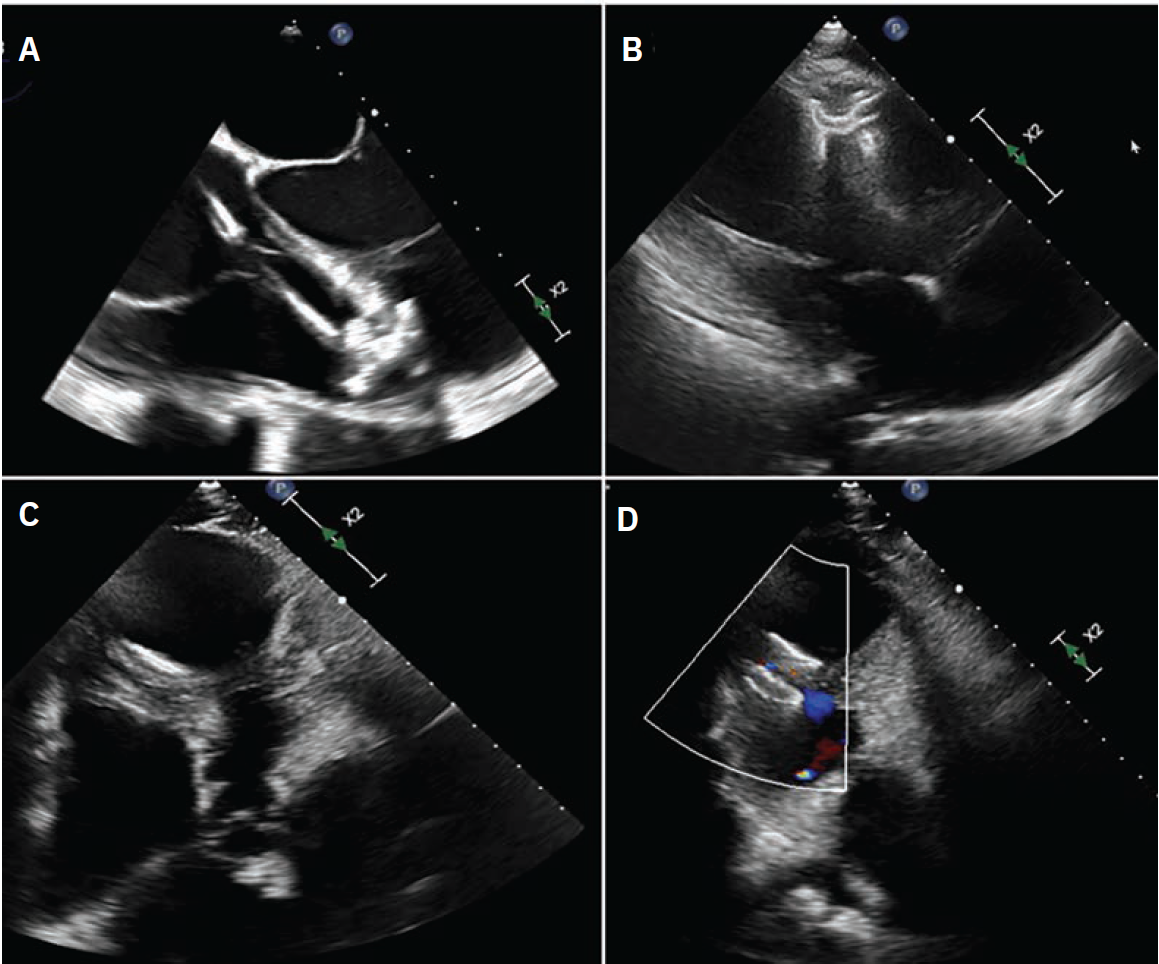

In October 2024, he presented with a one-month history of progressive dyspnea on exertion (DOE) and orthostatic dizziness. He denied chest pain. On examination, there was a loud, harsh, holosystolic murmur at left sternal border. Initial EKG showed Q waves with <2 mm ST elevations in leads V1-V3 and diffuse T wave inversions in the precordial leads, I and aVL (Supplementary Figure 2). Initial clinical diagnosis of delayed presentation of anterior STEMI with left ventricular (LV) aneurysm and VSD was confirmed with TTE which showed LV ejection fraction 20-25%, apical dyskinesis, and VSD with left-to-right flow on color Doppler (Figure 1, Video 1 [at end of case section]).

Imaging. Cardiac catheterization showed mild pulmonary hypertension, oxygen step up in right ventricle (RV) with Qp:Qs 2.8:1, severe native CAD, patent LIMA to LAD and RIMA to OM3. There was severe diffuse disease (90-95%) in the native LAD after the LIMA anastomosis (Figure 2, Video 2 [at end of case section]), which was the culprit behind the recent MI. Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) confirmed a large, antero-apical aneurysm and postinfarct VSD that measured up to 14 mm (Video 1 [at end of case section]). During multidisciplinary heart team discussion, he was deemed high risk for redo open heart surgery (LV aneurysmectomy and patch VSD closure) and was referred for percutaneous VSD closure.

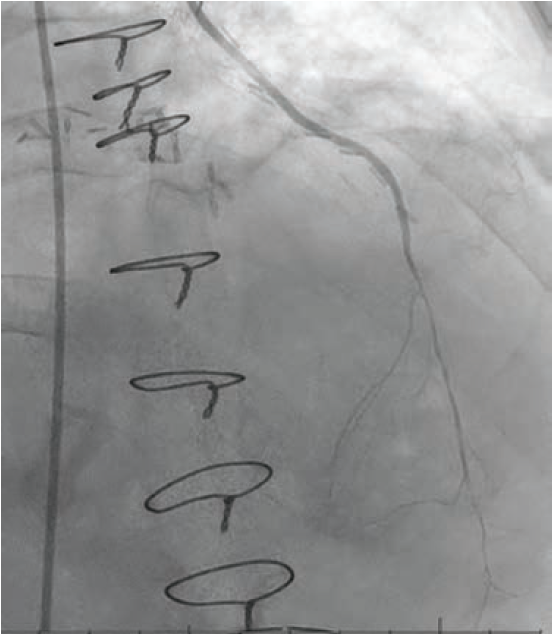

Procedure. Percutaneous VSD closure was performed under general anesthesia and TEE. Right femoral artery and right internal jugular (IJ) vein access was obtained. A 6 French (Fr) wedge catheter was placed in the pulmonary artery (PA). A 25 mm Goose Neck snare (Medtronic) was then advanced and opened in the main PA. The VSD was crossed using an exchange-length .035-inch Wholey wire with a Judkins Right (JR4) diagnostic catheter under TEE and fluoroscopic guidance. The Wholey wire was advanced into the PA. The wire was snared from the PA and externalized from the right IJ vein sheath to establish an arteriovenous (AV) rail. Thereafter, a 9 Fr TorqueVue sheath (Abbott) was inserted via the right IJ vein and advanced into the LV. Following this, an 18 mm muscular VSD occluder was advanced into the sheath, and the LV disc was deployed and pulled against the interventricular septum, following which, the RV disc was deployed. After confirming stable device position, the central cable was released.

The final left ventriculogram showed no residual flow across the VSD (Video 3 [at end of case section]). Final echocardiographic images confirmed good position of the VSD occluder with no flow on color Doppler (Figure 3, Video 4 [at end of case section]). Right heart catheterization showed minimal step up in oxygenation (RA, RV, and PA saturation 68%, 72%, and 72%, respectively) with Qp:Qs 1.16:1.

Outcome and follow-up. The patient was extubated following the procedure and discharged home two days later. Given the large LV aneurysm, he was placed on a direct-acting oral anticoagulant in addition to guideline-directed medical therapy. He refused an implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

At the time of outpatient follow-up a few months later, the patient reported significant improvement in his symptoms. There was no systolic murmur on clinical exam and an intact VSD occluder was visualized on TTE, with no residual flow.

Video 1

Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography showing severely reduced LV function and VSD.

LV = left ventricular; VSD = ventricular septal defect.

Video 2

Diagnostic cardiac catheterization with native coronary angiography as well as bypass graft angiography revealing severe, diffuse disease in the LAD distal to LIMA anastomoses.

LAD = left anterior descending artery; LIMA = left internal mammary artery

Video 3

Left ventriculogram in LAO view at baseline and after deployment of 18 mm muscular VSD occluder.

LAO = left anterior oblique; VSD = ventricular septal defect.

Video 4

Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography after VSD closure showing well-seated occluder with no flow on color Doppler.

VSD = ventricular septal defect

Discussion

Given the rare incidence of VSD as a mechanical complication of MI, literature on this topic is limited to retrospective, observational studies with limited sample size. Surgical repair of PI VSD is associated with high operative mortality (~40% overall and ~60% in first 24 hours after MI) with the latest data published in 2022 showing no change in operative mortality over a 23-year time period.4 Transcatheter closure of PI VSD may be considered as an alternative approach; however, it is associated with higher rate of residual shunt or re-intervention in the acute period.5 Additionally, attempting percutaneous VSD closure in the acute phase can expand the rupture site due to slicing of the necrotic myocardial tissue while creating an AV rail. There is a risk that the device may pull through the defect, resulting in considerable enlargement of the VSD, which may render it “uncloseable” via percutaneous approach.6 Delaying the closure by 1-3 weeks to allow scarring around the rims of the defect is often preferred in clinical practice to achieve the best outcomes with intervention.7,8 However, the rupture site can expand abruptly, leading to sudden hemodynamic collapse and death,7 and making the timing of VSD closure an age-old dilemma. Surgical data show that waiting to close the PI VSD improves outcomes (operative mortality 18% if the surgery is delayed by a week vs. 54% in the acute phase).9 However, this approach introduces a selection bias whereby the sickest patients perish prior to the operation. Studies on percutaneous PI VSD closure also report high mortality in the acute phase (<14 days after MI) with a 30-day mortality rate of 40% compared to 23% in chronic phase ( ≥14 days after MI).8

Our patient had asymptomatic anterior MI at least a month prior to presentation, resulting in a large LV apical aneurysm and PI VSD. Fortunately, he survived the acute event despite developing a mechanical complication. He eventually presented with DOE and heart failure symptoms due to the large left-to-right shunt from the VSD. Given this timeline, we anticipated well-defined scarring around the rims of the defect. With the high risk of redo sternotomy due to the patient’s age and reduced LV function, we decided to perform percutaneous VSD closure. In our case, the VSD measured around 14 mm, which led to the selection of an 18 mm muscular VSD occluder.

The Amplatzer VSD occluder devices (Abbott), like the atrial septal defect (ASD) occluder devices, are sized according to “height” of the waist connecting the two disks; but unlike the ASD occluder devices, the disks are equal sized and the “width” of the waist (ie, distance between the two disks) is larger, given that these devices are designed for the ventricular myocardium, rather than thin atrial septum (eg, distance between disks is 7-10 mm for VSD occluders vs. 3 mm for ASD occluders). Classic teaching is to oversize the VSD occluder device by at least 2-4 mm; therefore, we chose an 18 mm occluder for our case.

The muscular VSD occluder is designed for congenital VSD closure; however, it can be used for PI VSD closure for VSDs <16 mm in diameter. There is a dedicated PI VSD occluder device that requires institutional review board approval prior to use, and it differs from the muscular VSD occluder as follows: (1) The largest available size is 24 mm (range 16-24 mm) compared to 18 mm with muscular VSD occluder (range 4-18 mm); (2) the “width” of the device is larger (10 mm) compared to muscular VSD occluder (7 mm); and (3) the disk diameter is slightly larger (eg, disk diameter in an 18 mm PI VSD occluder is 28 mm vs. 26 mm in an 18 mm muscular VSD occluder).

For larger PI VSDs (ie, 16-22 mm), the PI VSD occluder or an ASD occluder can be used. For very large VSDs (>24 mm), an ASD occluder can be used, and use has been reported in PI VSD up to 38 mm in diameter.10 In addition, considering the poor tissue integrity of the myocardium in the acute phase, it is important to considerably oversize the ASD occluder, given the shorter distance between the two disks of the device, which may result in significant foreshortening of the device after deployment.6

Conclusion

Our case represents an uncommon (and lucky) scenario wherein the patient survived an anterior MI complicated by ventricular septal rupture, and presented over a month later with dyspnea and heart failure due to the large left-to-right shunt from the VSD. There is one prior case in the literature recording a 3-year survival in an untreated postinfarct VSD.1 In our case, the duration of the PI VSD is unknown (>30 days based on the clinical presentation). This case underscores the complexities involved in the diagnosis and management as well as the unpredictable nature of post MI VSD, and the safety and technical success of percutaneous closure.

References

1. Rexha N, Krasniqi X, Dervishaj Rexha A, Bakalli A. Overlooked ventricular septal defect Post-myocardial infarction and coronary artery bypass grafting. Clin Med Insights Case Rep. 2024; 17: 11795476241281442. doi:10.1177/11795476241281442

2. Evans MC, Steinberg DH, Rhodes JF, Tedford RJ. Ventricular septal defect complicating delayed presentation of acute myocardial infarction during COVID-19 lockdown: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. Feb 2021; 5(2): ytab027. doi:10.1093/ehjcr/ytab027

3. Jalli S, Spinelli KJ, Kirker EB, et al. Impella as a bridge-to-closure in post-infarction ventricular septal defect: a case series. Eur Heart J Case Rep. Oct 2023; 7(10): ytad500. doi:10.1093/ehjcr/ytad500

4. Dimagli A, Guida G, Sinha S, et al. Surgical outcomes of post-infarct ventricular septal defect repair: Insights from the UK national adult cardiac surgery audit database. J Card Surg. Apr 2022; 37(4): 843-852. doi:10.1111/jocs.16178

5. Aramin MAS, Abuhashem S, Faris KJ, et al. Surgical closure versus transcatheter closure for ventricular septal defect post-infarction: a meta-analysis. Ann Med Surg (Lond). Sep 2024; 86(9): 5276-5282. doi:10.1097/MS9.0000000000002294

6. Hribernik I, Bentham JR. Post-myocardial infarction ventricular septal defect closure with Gore Cardioform atrial septal defect occluder to improve tissue interactions: case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. Aug 2023; 7(8): ytad334. doi:10.1093/ehjcr/ytad334

7. Trivedi KR, Aldebert P, Riberi A, et al. Sequential management of post-myocardial infarction ventricular septal defects. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. May 2015; 108(5): 321-330. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2015.01.005

8. Sabiniewicz R, Huczek Z, Zbronski K, et al. Percutaneous closure of post-infarction ventricular septal defects-an over decade-long experience. J Interv Cardiol. Feb 2017; 30(1): 63-71. doi:10.1111/joic.12367

9. Arnaoutakis GJ, Zhao Y, George TJ, et al. Surgical repair of ventricular septal defect after myocardial infarction: outcomes from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database. Ann Thorac Surg. Aug 2012; 94(2): 436-443; discussion 443-444. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.04.020

10. Long A, Talreja A, Baran D, Talreja D. Percutaneous closure of a large postinfarct ventricular septal defect with an atrial septal defect closure device in a high surgical risk patient. J Invasive Cardiol. Jun 2021; 33(6): E485-E486. doi:10.25270/jic/20.00547