Femoral Vein Reconstruction: A Complicated Case Example Treating Chronic Venous Disease With a Modified Gun-Sight Technique

Key Summary

- A 42-year-old man with CEAP 6 disease and congenital absence of the left common femoral vein underwent recanalization using a modified gun-sight technique with covered stent reconstruction.

- Post-procedure ultrasound at 1 month and venogram at 4 months showed patent stents with reduced venous insufficiency, marked limb-size reduction, ulcer closure within 2 weeks, and improved mobility sustained at 1 year.

- This case report demonstrates the feasibility of adapting the gun-sight technique to extrahepatic venous occlusions when standard options are lacking; however, evidence is limited to a single case, with uncertain long-term durability and no comparator data.

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Vascular Disease Management or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

VASCULAR DISEASE MANAGEMENT. 2025;22(12):E102-E109

Abstract

Chronic venous disease is associated with significant patient morbidity, and not all cases are easily managed with traditional techniques. We report a case of common femoral vein occlusion in a patient with Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome. Successful reconstruction of the patient’s common femoral vein was made possible using the gun-sight technique, originally developed by Haskel et al for intrahepatic interventions. This case highlights the adaptability of endovascular methods and underscores the role of interventional radiology in providing novel therapeutic options for patients previously without hope.

Introduction

Venous diseases historically have received limited attention from both the medical community and the public. This was due, in part, to the limitations of therapies and devices specific to the venous system, making intervention difficult. In recent years, however, advances in treatment options have increased awareness.

Venous diseases create a significant burden on our current medical system. While exact numbers are difficult to identify, with studies varying in range often due to inclusion criteria, all studies indicate high prevalence and financial impact. Chronic venous disease may affect up to 25% of the population. Symptomatic chronic venous insufficiency alone affects 5% to 10% of the U.S. population, with cost estimates of $3 to $15 billion per year.1,2 Acute venous disease, referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE), includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism. VTE accounts for up to 500,000 hospital admissions and as many as 100,000 deaths annually. This adds a direct cost of $5 to $10 billion and an overall economic loss estimated at nearly $70 billion.3 Despite all these data, the drastic influence of venous disease remains widely under-recognized and underappreciated.

Studies indicate that as many 20% to 60% of individuals with VTE will develop long-term sequelae.4 Pathologies range from superficial venous reflux to post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS). These patients may experience mild to severe swelling, with many developing complications such as ulceration. While some cases are simple to manage, others create both a diagnostic and therapeutic quandary, resulting in extended workups and sometimes years of wound care.

Often, these patients have underlying anatomic issues predisposing them to chronic venous disease and even acute complications such as VTE. The most recognized is May-Thurner syndrome, which involves compression of the left common iliac vein by the crossing right common iliac artery. This anatomy was first described by Dr. Virchow in 1851 and was delineated as a syndrome by Drs. May and Thurner in 1957.5 Several other compressive abnormalities in the pelvis have since been identified and are collectively known as nonthrombotic iliac vein lesions.6

There are, however, other anatomic causes for chronic venous disease that are much less common and thus may be harder to identify as well as more difficult to treat. Here, we present the case of a patient with complicated chronic venous disease.

Klippel-Trénaunay Syndrome

Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome (KTS) is an uncommon, congenital diagnosis. The syndrome was first described by Klippel and Trénaunay in 1900. The diagnosis is made with identification of the classic triad of cutaneous hemangiomas (port wine stains) and vascular anomalies combined with asymmetric overgrowth of soft tissues and bones of the limb.7 The vascular abnormalities can be of the arterial, venous, or lymphatic system. One of the most common identified changes in KTS are large venous varicosities that often have changes involving the underlying deep veins, including agenesis or atresia.8 These patients often present in infancy or early childhood with skin stigmata and/or venous varicosities.

Case History

Our patient is a 42-year-old man with a history of congenital heart defect with pacemaker placement. He has bilateral leg edema and carries a diagnosis of lymphedema. However, he also has a lifelong history of asymmetric left leg enlargement. At age 35, his leg symptoms became more severe, and he developed bleeding varicosities of the left foot. He was referred to a regional tertiary center for acute management. At that time, he underwent localized sclerotherapy to control the bleeding. After further workup, he was given the diagnosis of KTS. While additional proximal superficial venous abnormalities were identified, further superficial venous intervention was deferred, given the underlying venous anatomy and concerns regarding the risk of DVT. A year later at follow-up, he had persistent symptoms and underwent additional localized sclerotherapy.

Since that time, the patient experienced worsening swelling despite those treatments. He continued to struggle with intermittent wounds. More recently, he presented to a local outpatient vein center, where ultrasound and clinical evaluation documented significant perforator vein reflux in the thigh, felt to be at least partially responsible for the superficial venous insufficiency. With combined venolymphatic changes, he was prescribed a lymphedema pump and referred for deep vein evaluation prior to any attempted superficial venous therapy options.

At the time of presentation to our clinic, the patient had a well-documented long-term history of venous symptoms with Clinical-Etiology-Anatomy-Pathophysiology (CEAP) 6 disease and severe mobility limitations, being restricted almost entirely to a wheelchair. His current medications included rivaroxaban and diuretic therapy, as well as digoxin and a beta-blocker for his congenital cardiac condition.

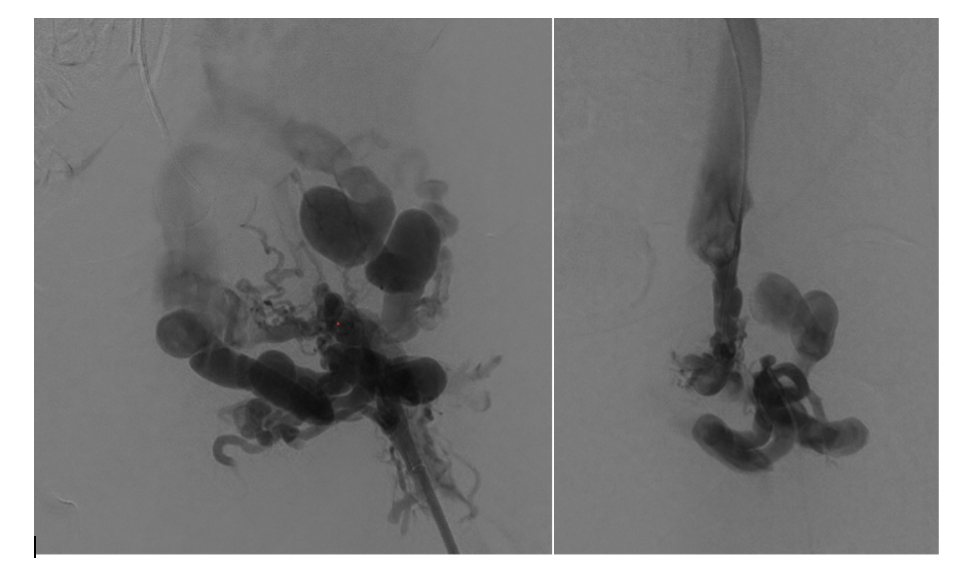

As part of our workup, a computed tomography (CT) venogram was performed. The most important anomaly noted was the absence of a normal left common femoral vein. There were adjacent branches or rudimentary femoral channels terminating near the level of the inguinal ligament, both superior and inferior. Between the closest proximities of these vessels was a roughly 1-cm gap. More proximally, his left iliac veins appeared to be intact (Figures 1 and 2).

The CT images provided sufficient information for intervention planning; with the obvious anatomic changes and the patient’s underlying cardiac history, we elected not to perform a combined diagnostic venogram and intervention to eliminate risk related to a second encounter.

This was not a common vein procedure and longevity of outcome in this location was difficult to predict. A literature search was performed but did not identify direct comparison cases to document “legitimacy” of the potential recanalization with stent placement in this location. Extrapolating from recanalization procedures of patients with KTS at other sites and similar procedures for PTS at the femoral level, we felt there was adequate potential benefit to warrant an attempt at femoral vein reconstruction.9

Procedure

The initial portions of the procedure were standard for our practice. The patient was positioned supine, with his left leg in the “frog” orientation. Standard sterile preparation was utilized with exposure of both inguinal regions and the left popliteal fossa. Ultrasound identified a widely patent left popliteal vein. We gained micropuncture access to the left popliteal vein and performed an antegrade venogram.

As no occlusions were identified distally, an 8F 45-cm Pinnacle sheath (Terumo) was introduced and advanced to the left femoral confluence. Next, right femoral vein access was achieved with similar technique. Using a 5F Cobra Glidecath (Terumo) and Glidewire Advantage (Terumo), access to the contralateral left common iliac vein was acquired. An 8F 45-cm Pinnacle sheath was placed and advanced over the carina to the left external iliac vein.

Venography was performed in multiple projections. The left groin exposure was utilized for ultrasound assessment of the target vessels. The cephalad channel appeared to parallel the left common femoral artery representing the anatomic location of the normal common femoral vein. The caudal channel was slightly deeper and posterior to the common femoral artery (Figures 3 and 4).

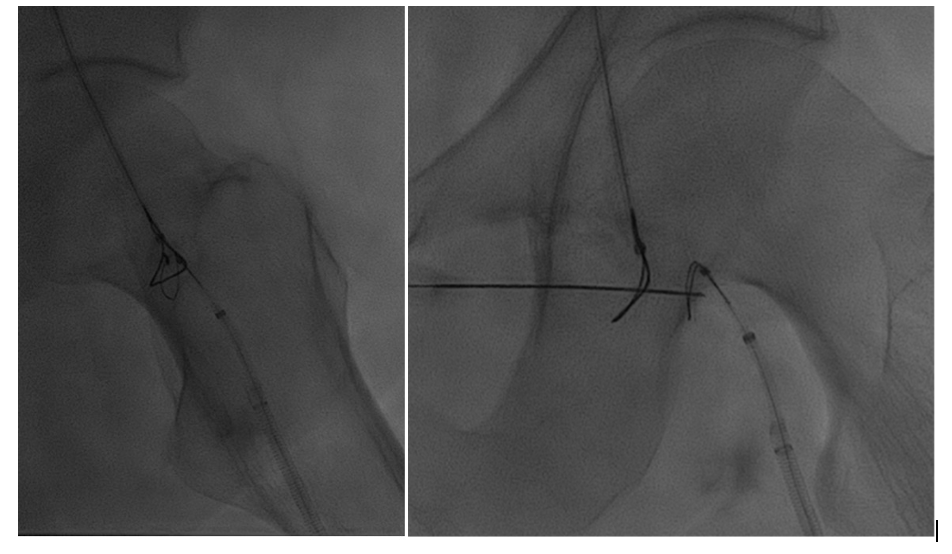

Using both ultrasound and fluoroscopy, we triangulated what we felt to be the appropriate trajectory for recanalization with safest access medial to the artery from a right anterior oblique approach (Figures 5 and 6).

Snare catheters (15-mm Amplatz Goose Neck [Medtronic]) were then placed bidirectionally and advanced to the most distal position in the truncated target channels. These were rotated to the appropriate position for planned recanalization. Percutaneous micropuncture access was then performed with ultrasound and fluoroscopy across both snare catheters, utilizing the modified gun-sight technique10 originally developed by Haskal et al11 (see Appendix).

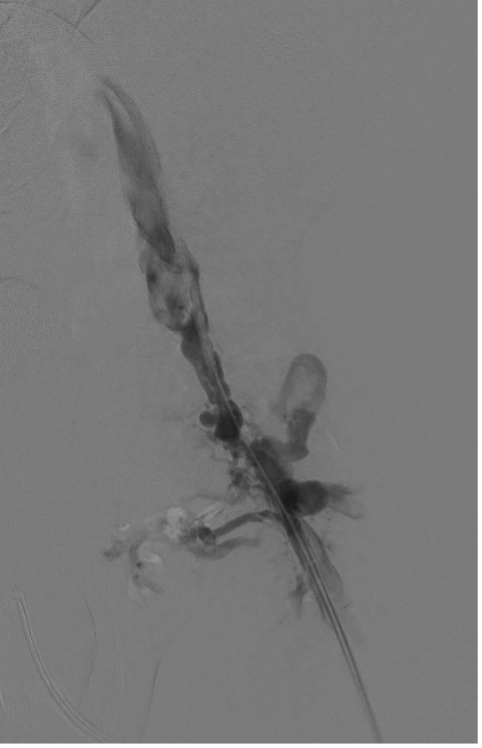

A 300-cm, .014-inch Fathom wire (Boston Scientific) was placed through the percutaneous needle and snared through each access sheath. With through-and-through access achieved, a direct femoral channel was established. Serial balloon angioplasty was performed with intermittent venography. Intravascular ultrasound (Philips) evaluation was also performed to document the channel. This showed a short segment of “uncovered” tract without visualization of the vein wall. At the same level, venography showed a small amount of extravasation of contrast, as expected. There continued to be filling of the large inguinal collateral veins, even after balloon dilation to 8 mm (Figure 7).

Given these findings, the decision was made to place a covered stent in the common femoral vein segment to exclude the “uncovered” channel and the persistent collaterals. A 10 x 50-mm Viabahn stent graft (Gore) was placed across the recanalization tract, reestablishing the anatomic common femoral vein. This was reinforced and extended into the left external iliac vein with a 12 x 80-mm Venovo venous stent (BD). The entire stent length was postdilated to 10 mm using a 10 x 40-mm Conquest 40 balloon (BD).

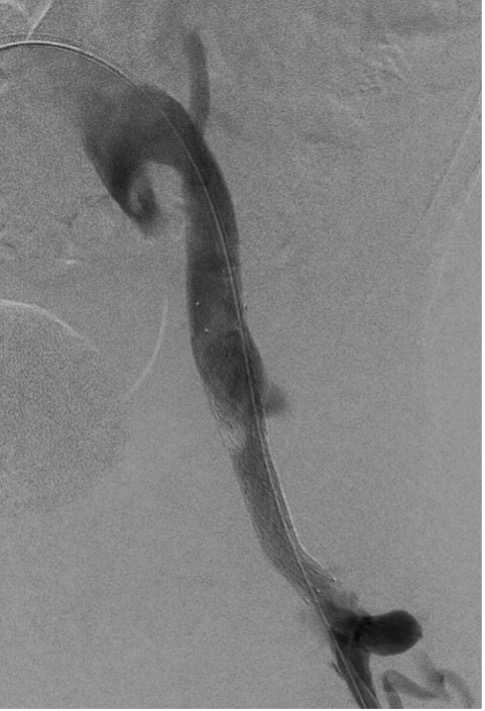

The final venogram showed a patent left common femoral vein confluence with inflow from the superficial femoral vein and the profunda femoris vein. Brisk outflow through the stent and draining iliac veins was demonstrated, with no residual extravasation, and the desired exclusion of the persistent inguinal collaterals (Figure 8).

Per clinic protocol, the patient was seen for an ultrasound and clinic visit at 1 month. Due to travel distance, this was performed by the collaborating vein center. The ultrasound showed a patent stent with marked reduction in previously documented venous insufficiency. At that time, the patient reported a significant weight loss and a marked reduction in leg size. He was successfully utilizing the lymphedema pump twice daily and mobility was increased as well. The patient stated his venous ulcer closed 2 weeks after stent placement (Figure 9).

Subsequent follow-up included a diagnostic venogram at 4 months that showed widely patent stents. The numerous collaterals previously seen in the left proximal thigh no longer extended into the pelvis. Widely patent profunda femoris vein and duplicated superficial femoral vein inflow branches were documented (Figure 10).

Most recently, 1-year follow-up imaging and clinical evaluation show the persistence of these positive results. The patient continued to improve his mobility and is now able to ambulate short distances. He has had no reoccurrence of ulcerations.

Conclusions

Patients can experience years of symptoms related to venous disease. While for many the therapeutic options are routine, for some no standard treatments exist. These patients may have been seen in multiple practices over a period of years and may have been told they have no hope of relief. These patients often present with frustration, and evaluation can be difficult and extensive.

Recanalization of venous occlusions can offer significant clinical benefit. While long-term stent patency rates following venous occlusion are not as high as in nonthrombotic patients, the current literature indicates the ability to maintain patency in the vast majority of patients.

The gun-sight technique, previously described for transhepatic interventions, can be extrapolated to extrahepatic sites for management of vascular occlusive disease. In the spirit of Dr. Dotter and the development of interventional radiology, it is important to remember that when traditional techniques prove insufficient, incorporating lessons from other procedures and disease states may offer a welcome solution. n

Affiliations and Disclosures

Dr Tiede is from the University of Michigan Health-West in Wyoming, Michigan.

Manuscript accepted November 18, 2025.

Dr Tiede reports that he has been on the speaker’s bureau and/or has provided consultant services for the following companies: Becton, Dickinson, and Company; Penumbra Inc.; Boston Scientific Corp.; and WCG Clinical Inc.

Address for Correspondence: Matthew A. Tiede, MD, University of Michigan Health-West, 6900 Byron Center Ave SW, Wyoming, MI 49519. Email: mtiede13@gmail.com

Appendix

Gun-Sight Technique (Haskal)—Step-by-Step

A. Planning & Setup

- Imaging & trajectory planning

Review computed tomography angiography/magnetic resonance angiography/ultrasound to define the proximal and distal true lumens, gap/occlusion length, nearby artery/nerve, and safe skin windows. Mark the intended skin entry with ultrasound if superficial structures are at risk. - Access & anticoagulation

Obtain 2 vascular accesses that can reach the proximal and distal ends of the occlusion (eg, contralateral femoral + ipsilateral popliteal for lower-extremity venous work). Heparinize to target activated clotting time per local protocol. - Sheaths & working catheters

Place appropriate sheaths; advance catheters with snares (eg, 10- to 20-mm Amplatz Goose Neck [Medtronic]) to the face of the occlusion from both directions (1 proximal, 1 distal).

B. Create the “Gun-sight” Target

- Snares into position

Open each snare so the 2 loops “face” each other across the gap—each sits flush against its occlusion cap. - Orthogonal fluoroscopic alignment

Using 2 planes (anteroposterior/oblique), superimpose the 2 snare loops so one sits concentrically inside the other—the classic “bullseye/gun-sight” view. Minor catheter torque and table angulation help perfect the alignment.

C. Needle Crossing

- Skin entry & needle selection

Choose the safest skin window (often medial to adjacent artery if in the groin). Use a micropuncture needle (≈21G) or long Chiba/spinal needle. - Fluoroscopy-guided needle pass

Under biplane fluoroscopy (and ultrasound, if helpful), advance the needle through the center of the superimposed snares, traversing the occlusion/gap. Maintain the bullseye in both planes to avoid off-target passage. - Confirm intraluminal position

Gentle contrast injection through the needle should opacify one of the snared lumens. If not, readjust before proceeding.

D. Guidewire Externalization (“Through-and-Through”)

- Wire delivery

Advance a .014- to .018-inch wire (long, eg, 300 cm) through the needle. The distal snare captures the wire and externalizes it.

– Option: Pass the wire into a microcatheter first if trackability is poor. - Complete the rail

Withdraw the needle. Use the proximal snare to capture and externalize the wire from the opposite side, creating a through-and-through working rail.

E. Channel Creation & Scaffold

- Predilation

Over the externalized wire, perform sequential balloon dilations (small → larger) across the newly created channel. Use intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) to confirm intraluminal course, diameter, and any uncovered tract.

12. Definitive therapy

- Covered stent to exclude an uncovered extravascular tract or persistent collateral diverting flow.

- Bare venous stent if a mature venous segment requires scaffolding without leakage risk.

- Post-dilate to target diameter (eg, 8-12 mm venous, anatomy-dependent).

- Completion imaging

Venography (± IVUS) to confirm brisk inflow/outflow, exclusion of collaterals/extravasation, and optimal stent expansion/apposition.

F. Post Procedure

- Hemostasis & access management

Remove catheters/sheaths per standard; ultrasound-guided compression or closure devices as appropriate for the access sites. - Antithrombotic regimen & follow-up

Resume/continue therapeutic anticoagulation (eg, direct oral anticoagulant/warfarin per institutional practice for venous stents), add antiplatelet if indicated, and schedule duplex/IVUS or venogram surveillance (eg, 1, 3-6, and 12 months).

Pearls & Pitfalls

- Pearl: The entire technique lives or dies by true biplane alignment. Maintain the concentric “gun-sight” throughout the needle pass.

- Pearl: IVUS early and often. IVUS can help confirm true lumen/landing zones and detect uncovered tracts that merit a covered stent.

- Pitfall: Deflecting toward the adjacent artery or nerve. Select a skin entry that maintains a medial trajectory and minimizes risk of arterial wall violation.

- Pitfall: Losing rail tension. Secure both ends before ballooning; consider snare-assisted microcatheter exchange if device advancement is impeded.

- Indications for covered stent placement: Evidence of contrast extravasation, a defined extravascular tract, or persistent collateral filling that contributes to reflux.

References

1. Kim Y, Png CYM, Sumpio BJ, DeCarlo CS, Dua A. Defining the human and health care costs of chronic venous insufficiency. Semin Vasc Surg. 2021;34(1):59-64. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2021.02.007

2. Lohr JM, Bush RL. Venous disease in women: epidemiology, manifestations, and treatment. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57(4 Suppl):37S-45S. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2012.10.121

3. Grosse SD, Nelson RE, Nyarko KA, Richardson LC, Raskob GE. The economic burden of incident venous thromboembolism in the United States: a review of estimated attributable healthcare costs. Thromb Res. 2016;137:3-10. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2015.11.033

4. Ashrani AA, Heit JA. Incidence and cost burden of post-thrombotic syndrome. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2009;28(4):465-476. doi:10.1007/s11239-009-0309-3

5. Harbin MM, Lutsey PL. May-Thurner syndrome: history of understanding and need for defining population prevalence. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(3):534-542. doi:10.1111/jth.14707

6. Desai KR, Sabri SS, Elias S, et al. Consensus statement on the management of nonthrombotic iliac vein lesions from the VIVA Foundation, the American Venous Forum, and the American Vein and Lymphatic Society. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17(8):e014160. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.124.014160. Erratum in: Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17(9):e000093. doi:10.1161/HCV.0000000000000093

7. Pavone P, Marino L, Cacciaguerra G, et al. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, segmental/focal overgrowth malformations: a review. Children (Basel). 2023;21;10(8):1421. doi:10.3390/children10081421

8. Asghar F, Aqeel R, Farooque U, Haq A, Taimur M. Presentation and management of Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: a review of available data. Cureus. 2020;12(5):e8023. doi:10.7759/cureus.8023

9. Kao SD, Srinivasa RN, Callese T, Jamshidi N, Plotnik A. Looking beyond the gunsight: a potential bailout technique for arterial and venous recanalization. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2022;28(3):260-263. doi:10.5152/dir.2022.21095

10. Lukies M, Moriarty H, Phan T. Modified gun-sight transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt technique. Br J Radiol. 2022;95(1140):20220556. doi:10.1259/bjr.20220556

11. Haskal ZJ, Duszak R Jr, Furth EE. Transjugular intrahepatic transcaval portosystemic shunt: the gun-sight approach. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1996;7(1):139-142. doi:10.1016/s1051-0443(96)70750-9