Are Lytic-Based Thrombectomy Devices Still Relevant?

Key Summary

- Large-bore, non–lytic-based thrombectomy for venous disease appears at least as effective as lytic-based therapy, with dramatically reduces rates of major bleeding or intracranial bleeding, and often lower hospital resource use because cases are typically single-session and generally do not require an ICU stay.

- Lytics may still help when clot burden is diffuse in small branches. Overall use has declined in practice, with clinicians awaiting further randomized controlled trial data (eg, HI-PEITHO) to refine patient selection.

- As studies continue to demonstrate comparable efficacy with an improved safety profile, lytic-based therapy will likely become less relevant over time.

© 2026 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Vascular Disease Management or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

McLaren Health, Bay City, Michigan

VASCULAR DISEASE MANAGEMENT. 2026;23(1):E1-E2

At the 2025 VEITHsymposium New York, Nicolas J. Mouawad, MD, MPH, MBA, from McLaren Health in Bay City, Michigan, gave a presentation entitled “Are Lytic-Based Thrombectomy Devices Still Relevant in 2025?” Vascular Disease Management spoke with Dr Mouawad about the presentation and how non–lytic-based therapies provide a better safety profile and lower bleeding risk.

Your presentation asks whether lytic-based thrombectomy devices are still relevant in 2025. What are the main clinical or technological trends that have prompted this question? And are there specific patient outcomes or procedural data that suggest a shift away from these devices?

Historically, the treatment of patients with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism has primarily been lytic based. Most of the data and existing guidelines are based on lytic-based therapies.

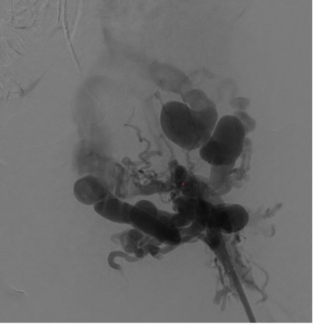

However, with the advent of large-bore mechanical thrombectomy and aspiration devices that are non–lytic-based, I believe there is a trend toward these newer technologies. The primary reason is safety. With lytics, there are complications and concerns about bleeding, which we have traditionally accepted in exchange for good outcomes. such as early restoration of flow, thrombus resolution, and improvement in right ventricular function. There are a variety of factors, but we accept the risk because we want patients to obviously do better with the resolution of the clot

Now, we can often achieve those same goals without lytics. So the question becomes: why accept even a small percentage of major or intracranial bleeding events when they can be avoided? These complications can be very problematic.

There is also a growing body of data supporting non–lytic-based approaches, including the FLAME Registry, FLASH data, and newer studies such as the STORM-PE trial and PEERLESS II, which demonstrate the benefits of large-bore, non–lytic-based thrombectomy.

With newer thrombectomy technologies emerging, how do lytic-based systems compare in terms of efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness?

That’s a great question. We find that non–lytic-based therapy tends to be at least as effective, and in many cases more effective, than lytic-based approaches—although lytic therapies themselves are effective.

The major concern is safety. With large-bore, non–lytic-based devices, there are minimal rates of significant bleeding or intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). In fact, data on some large-bore, non-lytic based devices have a zero event rate of ICH in some cohorts or very low incidences (<1%) in larger registries, especially when compared to systemic thrombolysis. From a cost-effectiveness standpoint, we find a reduction in cost of non–lytic-based therapy because lytic-based cases require nursing capital and ICU care, which are the most expensive resources in the hospital. They require repeat procedures, which are also very costly.

In contrast, large-bore non–lytic-based thrombectomy is typically a single-session procedure, which has been shown over time to reduce overall hospital costs for the episode of care.

Are there particular patient populations, clot characteristics, or anatomical situations where lytic-based approaches still offer advantages?

I don’t think lytic-based therapy will go away completely.

There are small scenarios in venous disease where I think lytics remain effective, particularly when there are numerous small clots distributed across multiple branches. It can be challenging to mechanically remove every clot with a large-bore device. When you find a lot of clot in a lot of small branches, lytic therapy can play a prominent role because it allows medication to be infused and distributed throughout those smaller branches more effectively.

That said, in our practice, the use of lytic-based therapy has decreased significantly. We are also looking forward to data from the new HI-PEITHO trial to further guide treatment decisions.

What are the key takeaways you wanted attendees to get from your presentation?

We believe upcoming randomized controlled trial data will show that intervention is beneficial for patients. We clearly want to minimize bleeding risk while maintaining high efficacy.

If we can treat patients effectively with excellent safety and minimal risk—and achieve good outcomes—then there is little reason not to intervene. As we continue to demonstrate comparable efficacy with a much better safety profile, lytic-based therapy will likely become less relevant over time. n