Outpatient Management of Subungual Melanoma: A Unique Case Study

Bob Marley was a gifted musician and lifelong philanthropist. For fans of his, it is well known that he succumbed to an unfortunate and early passing due to metastatic melanoma. In 1977, Marley was diagnosed with malignant melanoma under the hallux toenail. He declined to have a full digital amputation, and by 1981 he passed from a metastatic brain tumor, believed to be related to the original subungual lesion.1

There are many different types of melanoma such as acral lentiginous, superficial spreading, nodular, lentigo, nodular, and amelanotic melanoma. Many know the “ABCDEs” regarding melanoma, such that it can appear as a nevus but may have differentiating features of asymmetry, irregular borders, abnormal coloration, diameter beyond 6 mm, and if subungual, there can be vertical lines under the toenail.2 Up to 15% of all melanoma occurs in the foot and ankle.3 The cancerous cells can grow rapidly and become life threatening in a short period of time, quickly metastasizing if left untreated. The overall 5-year survival rate for patients with primary melanoma of the foot or ankle is 52%, compared to 84% in patients with primary melanoma elsewhere on the lower extremity.4 The most common areas for melanoma to develop on the feet are the soles, heels, interdigitally, and the toenails.5

In this article, we discuss a case of melanoma as a new lesion where previous trauma had occurred. This case speaks to the importance of early recognition, diagnostic techniques which include classification systems, using those classifications to guide intervention, and consideration of potential recurrence.

The Case Presentation

Our patient is a 56-year-old male who presented to the outpatient podiatry clinic at Denver Health with a referral for concerns regarding an ingrown toenail. He recalled a ladder falling on his left great toe 3 years earlier, and that the area has since become an enlarged growth. He expressed concerns about the appearance of the digit, as well. He had not undergone any previous evaluation for this toe and had no history of previous ingrown toenail. Past medical history at the time of presentation was unremarkable other than a history of tobacco use.

The patient denied pain upon palpation to the left hallux. He had palpable pedal pulses. Clinical examination revealed an open lesion to the left great toenail area (Figure 1), measuring 2.5 cm x 2.0 cm with a 75% granular base and 25% necrotic tissue. There was no odor, but there was mild serosanguinous drainage. A portion of the nail plate was intact with visible nail border spicules. Left foot X-rays did not show osseous involvement.

Due to concern for this nonhealing left toe wound, we took the patient was to the operating room for deep surgical biopsy, and obtained 4-mm punch biopsy of the left hallux distal skin, a 6-mm punch of the hallux nail bed, and 4-mm punch of the proximal nail fold. Surgical pathology found positive margins of melanoma to the left great toe and formalized a diagnosis of ulcerated invasive melanoma (Figure 2). Utilizing the Breslow classification, we determined that the thickness of this lesion was at least 4.7 mm. Histological sections of skin demonstrated atypical proliferation of melanocytic cells within the basilar epidermis. We discussed the results with the patient, including the high risk for amputation and promptly referred him to Oncology for further evaluation.

In addition to visits with interventional radiology and oncology for positron emission tomography (PET) analysis, the patient also had close follow-up in the outpatient podiatry clinic. The PET scan results showed increased metabolic activity at the left supraclavicular, axillary and inguinal lymph nodes. Podiatry performed regular wound care and began to engage the patient in conversations of potential left hallux amputation (Figures 3,4). Additionally, general surgery was consulted for sentinel node biopsy. The patient eventually consented to digital amputation. Podiatry undertook this intervention jointly with the general surgery service, who performed a lymphadenectomy of the superficial inguinal lymph nodes. Pathology on the lymph nodes did show metastatic melanoma morphologically similar to the primary lesion.

Shortly after the procedure, the patient presented to the emergency room with fever and vomiting for 6 days. The work-up resulted in admission for a surgical site infection to the left groin. The hallux amputation site was healing routinely. During this admission, concerns arose for potentially inadequate resection margins of the prior hallux amputation. After thorough review, the hallux exhibited a distance between invasive melanoma and peripheral clean margin of at least 12mm, which was under the recommendation of clean margin of 20 mm. Given these inadequate resection margins, podiatry recommended revisional amputation with 10 mm full thickness margins and resection of the distal first metatarsal head. Upon full informed consent, we brought the patient back for a third procedure which ultimately resulted in a partial first ray amputation. Intraoperative surgical pathology deemed the updated resection margins as adequate (Figure 5).

Addressing Concerns of Metastasis

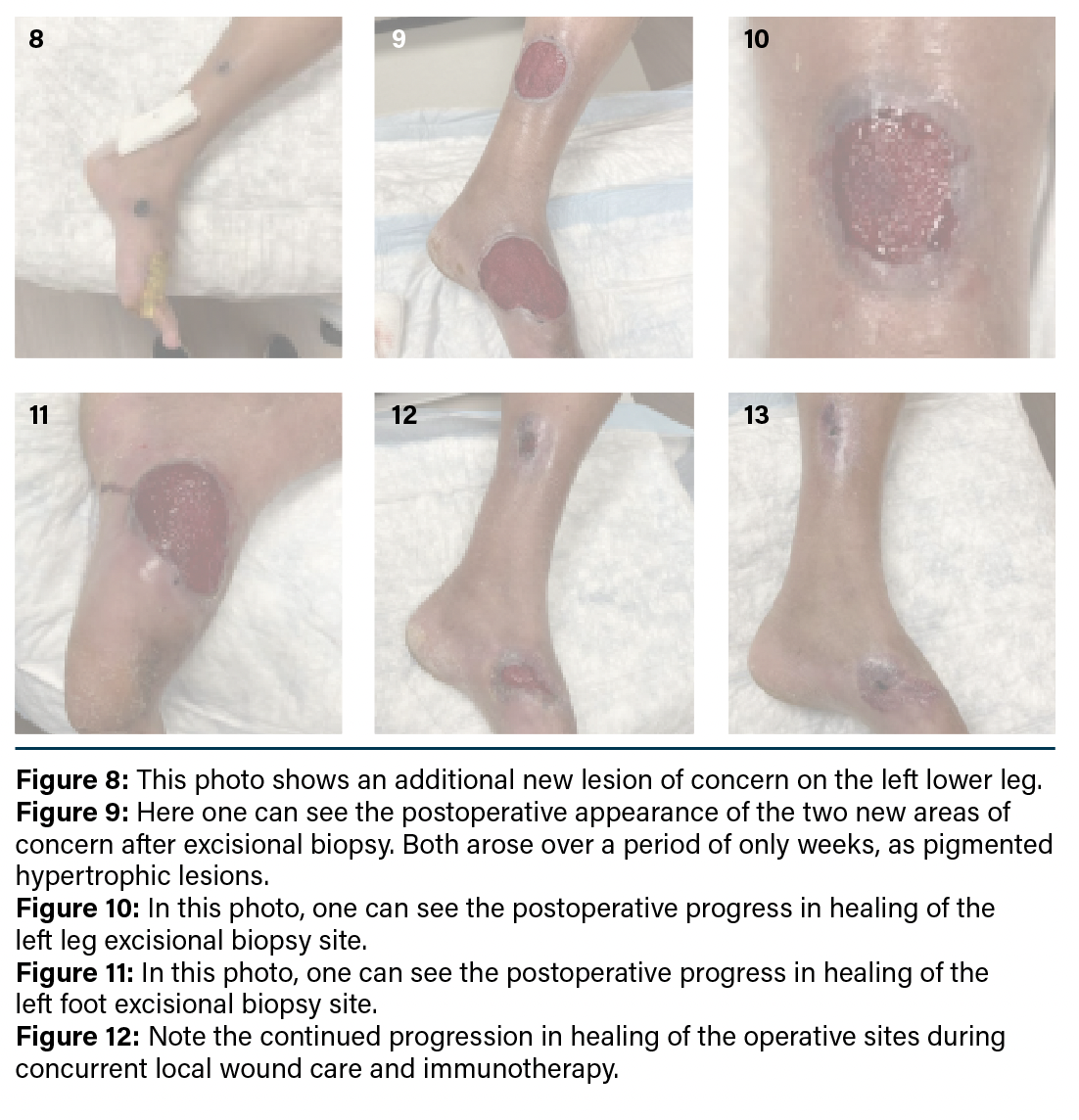

Although surgical pathology showed negative margins from the partial first ray amputation. concern emerged that the melanoma may have already progressed prior to the previous intervention. As the patient continued follow-up in the outpatient podiatry clinic, two new lesions appeared at the medial arch of the left foot and the medial aspect of the left leg. The patient admitted these lesions originated as small hypertrophic lesions with pigmentation that grew in size over the past few weeks (Figures 6, 8, and Figure 7 online). Upon further evaluation, ultrasound examination discovered a mass with internal vascularity suspicious for metastasis on the previously mentioned area of the medial left lower

extremity. The patient promptly underwent excisional biopsy of the left leg and foot lesions (2-cm circumferential margins) with negative pressure wound therapy application (Figure 9).

The patient continued to routinely follow with the outpatient podiatry clinic for continuity of care and wound management. He was also consistent with home wound care instructions. During this time, he also recieved D1C3 pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck) infusion treatment per oncology. The wound bases progressively improved and eventually healed entirely (Figures 10-12). At the most recent follow-up, the patient reported returning to work as a landscaper and continuing care with oncology for Keytruda infusions. He has persisted in his follow-up with oncology, but has experienced significant gastointestinal side effects from immunotherapy. His oncology team is considering further referral for possible alternatives such as tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy.

Leveraging Classification Systems for Melanoma Cases

This case underscores the importance of melanoma classification systems when planning surgical excision of malignant lesions. Historically, classifications primarily consisted of the Breslow and Clark depth classifications. While both systems measure depth, they are not interchangeable. Breslow thickness measures a lesion’s vertical depth of invasion into the body whereas the Clark level describes the anatomic depth of a lesion into the skin.6 The Breslow classification is measured in millimeters using a small ruler called a micrometer. The depth was a previous standard to determine how far melanoma has invaded into the layers below the surface skin. The deeper the measured depth, the higher the chance of significant malignancy.6 The Clark classification utilizes levels as opposed to specific skin depth. However, like the Breslow classification, the deeper the level a lesion extends to anatomically for its Clark level, the greater its chance of being malignant. Given that the Clark classification does not use specific measured depths, it was thought to be less diagnostic than the Breslow classification. While both classifications were previously widely used in melanoma staging, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) recently adopted the tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging system for melanoma.6 The new system is thought to be evidence based in treating malignancies based on their specific stage.

The stages help providers have a better idea of melanoma progression. Our job as surgeons is to communicate all operative findings with the patient and continued care. With the new approach, we feel the team can better discuss surgical findings (advancement of margins) with the patient. The discussion can relate findings to this classification system, with chances of progression or metastasis if staged highly. This not only provides clear communication with patients but also allows providers to have reason to act quickly and communicate with other teams to proceed with intervention in a timely manner.

For detailed figures and more information on the Breslow Depth, the Clark Level, and on AJCC Staging, readers can navigate to the Melanoma Research Alliance at https://tinyurl.com/bdf3ryt4.6

In Conclusion

As medical professionals are trained to know, changes to skin pigment, elevated lesions, abnormal change in size, shape, or texture of any skin lesion are noteworthy, and warrant biopsy. While many biopsy techniques are available, punch biopsies are the gold standard for management concerning underlying deep skin conditions. Crucial diagnostic steps include a thorough history for risk factors, inspection of the lesion using ABCDE criteria, using the Glasgow 7-point checklist, and looking for the “ugly duckling” sign, where one lesion is distinct from others.7 The American Academy of Dermatology guidelines/outcomes committee for Cutaneous Melanoma and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend initial excision with 1-to-3 mm margins.8 In conclusion, the goals of melanoma treatment include: early recognition, quick response, multiteam approach for appropriate care, ample patient and interprofessional communication, and continued evaluation and testing. Utilizing these approaches can support improved patient outcomes and set the standard for melanoma treatment.

Drs. Dubois, Studnicka, and Franklin are all third-year residents at Denver Health.

Dr. Gorski is an attending podiatrist at Denver Health.

1. Kyriakou G, Kyriakou A, Papanikolaou S, Glentis A. Don’t worry about a thing … every little thing gonna be all right (except for acral lentiginous melanoma). Clin Dermatol. 2022 Sep-Oct;40(5):613-616. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.11.011. Epub 2020 Dec 2. PMID: 36509509.

2. Heistein JB, Acharya U, Mukkamalla SKR. Malignant Melanoma. [Updated 2024 Feb 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470409/

3. Sondermann W, Zimmer L, Schadendorf D, Roesch A, Klode J, Dissemond J. Initial misdiagnosis of melanoma located on the foot is associated with poorer prognosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Jul;95(29):e4332. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004332. PMID: 27442685; PMCID: PMC5265802.

4. Walsh SM, Fisher SG, Sage RA. Survival of patients with primary pedal melanoma. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2003;42(4):193-8. doi: 10.1016/s1067-2516(03)70028-3. PMID: 12907929.

5. Moffitt Cancer Center. Common Locations for Melanoma. Published 2024. Accessed July 31, 2025. Available at: https://www.moffitt.org/cancers/melanoma/faqs/common-locations-for-melanoma/.

6. Melanoma Research Alliance. Breslow Depth and Clark Level. Accessed July 31, 2025. Available at: https://www.curemelanoma.org/about-melanoma/melanoma-staging/breslow-depth-and-clark-level

7. Pickett H. Shave and punch biopsy for skin lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(9):995-1002. PMID: 22046939.

8. Houghton AN, Coit DG, Daud A, National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Melanoma.

J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006;4(7):666-684.