Femoral Access Retrieval of Dislodged Leadless Pacemaker From the Pulmonary Artery

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of EP Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

EP LAB DIGEST. 2025;25(11):22-23.

Brittany Eaker, MSN, FNP-C1; Kolade Agboola, MD, FACC1; John Schindler, MD, FACC1; James Greelish, MD1; Rick Turek, BS, CCDS2; Gregory Woo, MD, FHRS, FACC1

1CaroMont Heart and Vascular Clinic, Gastonia, North Carolina, 2Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, Illinois

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old woman with a complex cardiac history including resection of a subaortic membrane, aortic stenosis post transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), and permanent atrial fibrillation with a left bundle branch block, presented with complaints of malaise, altered mental status, and fever. She had blood cultures that were positive for streptococcus secondary to osteomyelitis of the spine. The patient was also treated for C. difficile colitis. An infectious disease specialist was consulted and placed the patient on appropriate antibiotic therapy. She had a transesophageal echocardiogram and was ruled out for endocarditis. Her bacteremia was ultimately cleared. However, during this time, her heart rates were dropping into the 30s and 40s, mostly at night. Bradycardia continued to worsen, with the patient’s heart rates dropping into the 20s and pauses greater than 5 seconds. Permanent pacing was deemed necessary, and given the patient’s high infection risk, an AVEIR (Abbott) leadless pacemaker (LP) was recommended.

The patient underwent the pacemaker implant in our electrophysiology (EP) laboratory. A temporary transvenous pacing wire was placed from the left femoral vein (LFV) for backup pacing as the LP was being implanted. The LP was placed from the right femoral vein (RFV). The device was positioned onto the mid right ventricular (RV) septum. Prior to release of the device, device parameters (current of injury, impedance, sensing, and threshold) were checked and felt to be appropriate. The LP was released from the delivery catheter. Approximately 2 minutes after release, there was loss of capture noted on the cardiac monitor. Pacing was resumed through the temporary pacing wire. Fluoroscopy revealed dislodgment of the LP with embolization out into the left pulmonary arterial (PA) system. An attempt was made to retrieve the device with the AVEIR retrieval system. However, this was not a suitable tool for an embolized LP in the circuitous route of the PA system.

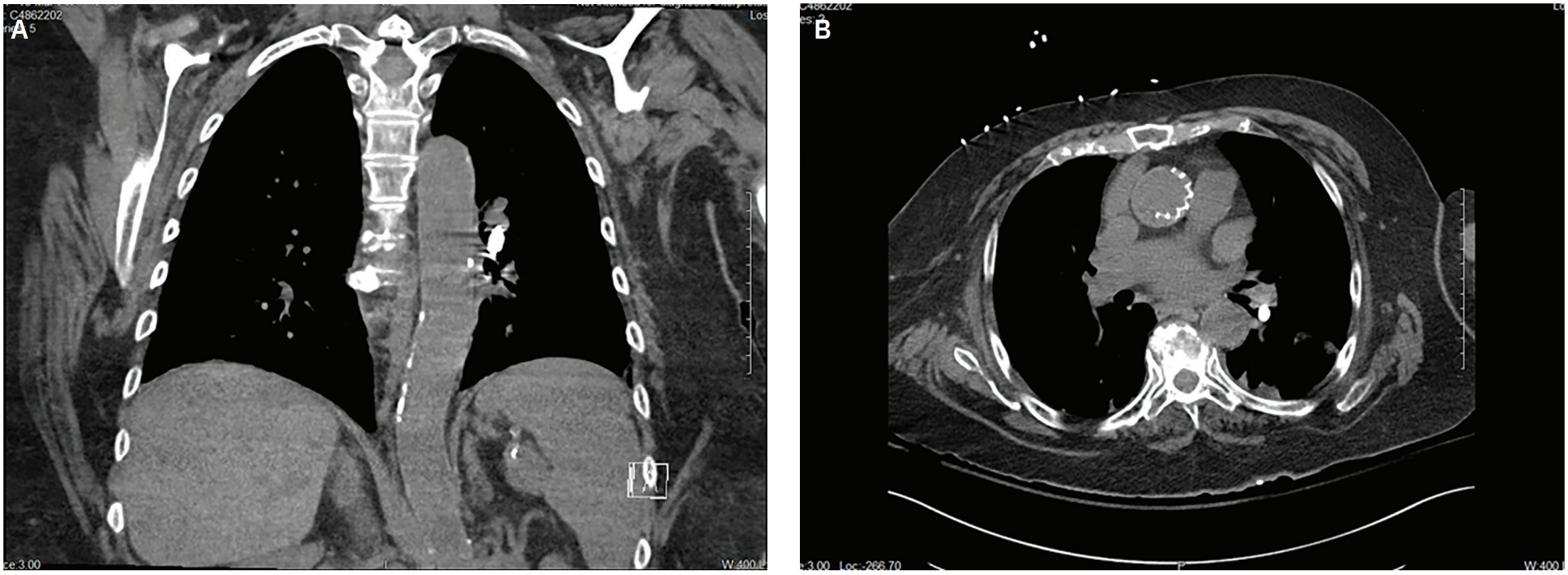

A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the chest was then performed (Figure 1), which detailed that the device had embolized to a posterior segmental branch of the left lower lobe of the PA.

After review of the CT and discussion with interventional cardiology, it was deemed that successful retrieval was feasible. The patient returned to the EP lab and a temporary pacemaker wire was placed through the right internal jugular (RIJ) vein with the temporary wire in the RFV removed.

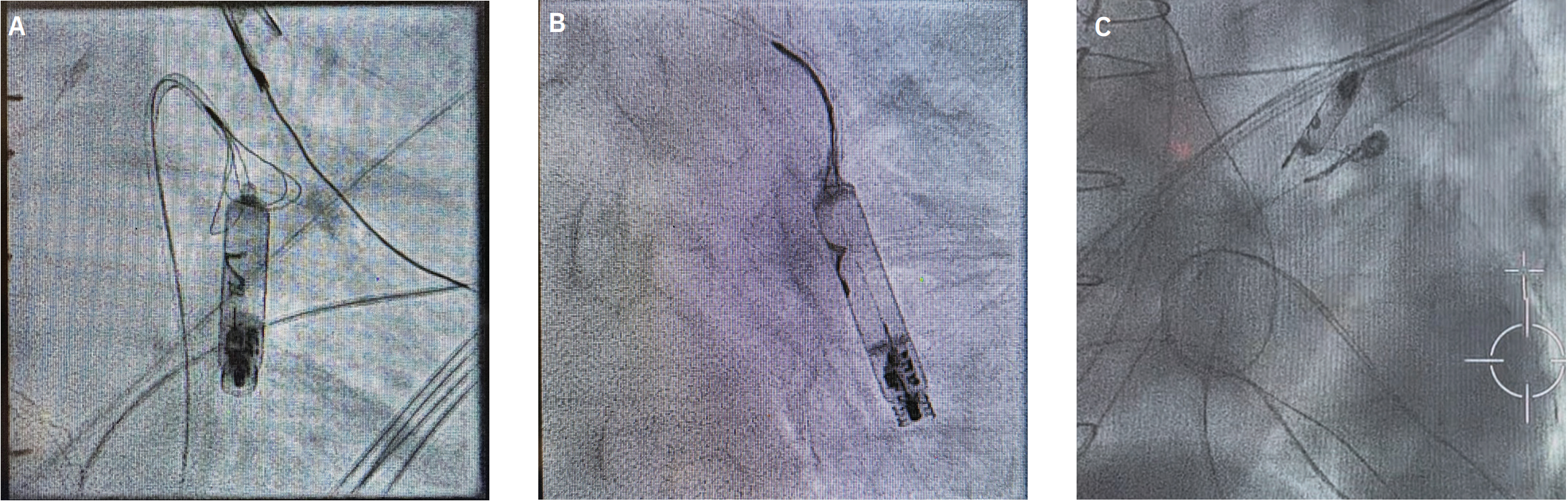

Next, a 27 French (F) AVEIR introducer sheath was placed in the RFV. A PA catheter (Swan-Ganz) was then placed through the sheath out into the left main PA. A .018” V-18 wire (Boston Scientific) was used to subselect the target branch in the posterior lower lobe. The PA catheter was removed and a 5F JR4 catheter was advanced over the .018” wire. The .018” wire was then exchanged for .035” Rosen wire (Cook Medical), over which the 5F JR4 was exchanged for a 6F JR4. Next, an EN Snare tri-loop snare (Merit Medical) was placed through the JR4 catheter and guided over the LP. The device was successfully secured and removed out of the body through the AVEIR sheath after approximately 20 minutes of procedure time. Then, a new AVEIR VR was advanced through the sheath and successfully implanted. Electrical parameters, including scrutinized current of injury, were excellent.

Discussion

Since the introduction of the first leadless pacemaker in 2012, the number of LP implants in the United States has increased significantly, from just over 3000 in 2016-2017 to nearly 12,000 in 2020.1

This trend is expected to continue given the advantages of LPs over traditional endovascular pacemakers, as they eliminate lead fractures and the necessity of a chest pocket. These devices offer a less restrictive and shorter recovery following implantation.2 Additionally, in our case, they reduce the likelihood of infection.3

These devices are not without complications and carry a unique problem. A lead dislodgment in a traditional endovascular pacemaker, especially acute, is relatively easily corrected. Although the dislodgment risk of leadless pacemakers is very low (.9%),4 this complication is more complex and requires additional tools and skill sets for retrieval.

There have been several case reports of successful retrieval of an embolized LP device,4 and traditional LP retrieval success rates are 87.6%.5 Our case demonstrates successful LP retrieval from the PA and replacement with a new LP re-implant.

Although the AVEIR pacing platform has a retrieval system that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, this might not work for a device that has embolized beyond the RV outflow tract. Most EP labs have the tools necessary for a successful retrieval. The essentials include a tri-loop snare, a guide catheter large enough to deliver the snare in proximity to the device, and various wires to negotiate the PA system to safely advance the guide catheter to the desired location.

In this case, a PA catheter was used to access the left PA system and a guidewire was placed through the PA catheter to subselect the branch. This allowed placement of a guide catheter (6F JR4) over the wire to the site and subsequent delivery of the snare with successful retrieval.

Our team utilized the 27F introducer sheath as a workstation that allowed us to not only remove the device from the body, but also re-implant a new device in the same setting.

Additional imaging can also be useful for specifically localizing where the device has migrated within the pulmonary arterial system as well as device orientation, as the docking end is preferable for snaring. The CT scan in this case proved helpful in preprocedural planning.

Summary

This case describes our initial experience with the retrieval of a LP from the PA. Careful procedure planning, fundamental interventional skills with wires and guide catheters, and a basic familiarity with snaring made this case successful. EP labs that implant LPs should become familiar with this complication and have the required personal and equipment for retrieval.6

Disclosures: The authors have completed and returned the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest, and have no disclosures to report. Rick Turek reports he is an employee of Abbott.

References

- Khan MZ, Nassar S, Nguyen A, et al. Contemporary trends of leadless pacemaker implantation in the United States. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2024;35(7):1351-1359. doi:10.1111/jce.16295

- Cantillon DJ, Dukkipati SR, Ip JH, et al. Comparative study of acute and mid-term complications with leadless and transvenous cardiac pacemakers. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15(7):P1023-1030. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.04.022

- El-Chami MF, Bonner M, Holbrook R, et al. Leadless pacemakers reduce risk of device-related infection: review of the potential mechanisms. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17(8):1393-1397. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.03.019

- Bahbah A, Sengupta J, Witt D, et al. Device dislodgement and embolization associated with a new leadless pacemaker. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2024;35(12):2483-2486. doi:10.1111/jce.16485

- Neuzil P, Exner DV, Knops RE, et al. Worldwide chronic retrieval experience of helix-fixation leadless cardiac pacemakers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2025;85(11):1111-1120. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2024.10.094

- McNamara GPJ, Haber ZM, Lee EW, et al. Successful removal of a leadless pacemaker from the pulmonary artery via a novel basket retrieval system. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2023;9(4):215-218. doi:10.1016/j.hrcr.2022.12.015