Comparison of Internal Jugular Versus Femoral Vein Access for CardioMEMS Implantation: A Single-Center Experience

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Cath Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Arif Albulushi, MD1; Duaa Alsinani, MD1; Saud A. Almarbuii, MD1; Ammar M. Al-Abedi, MD2; Malak A. Alkulaibi, MD1; Zahra Hosseini, MD3

1Division of Adult Cardiology, National Heart Center, The Royal Hospital, Muscat, Oman

2College of Medicine, National University of Science and Technology, Sohar, Oman

3Department of Radiology, Oman International Hospital, Muscat, Oman

Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Data Availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Approval No. 0833-22-FB), with informed consent obtained from all participants.

The authors can be contacted via Arif Albulushi, MD, FACC, FASE, FESC, FRCP (Glasg), Assistant Professor and Consultant, Advanced Heart Failure & Transplant Cardiology, at dr.albulushi@gmail.com.

Abstract

This single-center, retrospective study compares the feasibility and outcomes of internal jugular (IJ) versus femoral vein (FV) access for CardioMEMS Heart Failure System implantation (Abbott). Among 120 heart failure patients (60 IJ, 60 FV), we assessed procedural times, contrast volume, complication rates, and post-procedural outcomes. The IJ approach showed an average procedural time of 55 minutes versus 58 minutes for FV (P=.25) and used slightly less contrast (18 ml vs 20 ml, P=.30). Immediate complication rates were low in both groups, with no major adverse events. Six-month readmission rates were 15% in the IJ group and 17% in the FV group (P=.76).

Our findings suggest the IJ route is a viable alternative to femoral access, providing comparable procedural safety and efficacy, with potential advantages in patient comfort and reduced access-site complications. This study supports IJ access as a practical option for clinicians aiming to optimize CardioMEMS implantation outcomes.

Introduction

The CardioMEMS Heart Failure System (Abbott) has emerged as a revolutionary tool in heart failure management, enabling wireless monitoring of pulmonary artery pressure, a key indicator of heart failure exacerbation.1 Traditionally, femoral vein access has been the primary route for implanting this sensor.2 However, this approach, while widely practiced, is associated with challenges3 such as bleeding, infection, and anatomical limitations in certain patients, making alternative access routes worth exploring.4

The internal jugular (IJ) vein presents a promising alternative for CardioMEMS implantation.3 Its established use in central venous access across various medical procedures suggests its applicability and safety for CardioMEMS implantation.5 The IJ route may offer specific advantages, including a lower risk of bleeding, simpler post-procedural management, and enhanced patient comfort, particularly in outpatient settings.6 This advantage is particularly relevant in patients with advanced heart failure and pulmonary hypertension, where precise hemodynamic monitoring and vascular access play a critical role in optimizing clinical outcomes.7

Despite its benefits, the IJ approach is not widely used for CardioMEMS implantation, likely due to limited comparative data with femoral access. Our study addresses this gap by evaluating procedural aspects, complications, and outcomes between the two methods in a single-center setting. These findings aim to provide insights into the feasibility and effectiveness of IJ access, potentially informing procedural choices and improving heart failure management.

Methods

This single-center retrospective study analyzed 120 patients (60 per group) who underwent CardioMEMS implantation via internal jugular (IJ) or femoral vein (FV) access from January 2018 to December 2023. Data were collected retrospectively from electronic medical records, with patient consent obtained as part of standard clinical care during the implantation process, not specifically for research purposes. No prospective data collection was conducted beyond routine clinical follow-up.

Adult heart failure patients requiring CardioMEMS implantation at our center were included, with exclusions for active infection, pregnancy, or device contraindications. Access route was chosen based on anatomy, vascular history, and clinical factors, with IJ often selected for patients at higher bleeding risk or with previous femoral interventions.

Inclusion Criteria

• Adult patients aged ≥18 years.

• Diagnosed with heart failure (New York Heart Association [NYHA] Class III or ambulatory Class IV).

• Underwent CardioMEMS implantation at our center between January 2018 and December 2023.

• Eligible for pulmonary artery pressure monitoring as part of advanced heart failure management.

Exclusion Criteria

• Active systemic infection at the time of implantation.

• Pregnancy at the time of implantation.

• Prior failed CardioMEMS implantation attempt.

• Documented allergy to contrast media or anticoagulation contraindications.

• Severe coagulopathy (INR >2.5) or platelet count <50,000/μL at the time of the procedure.

CardioMEMS implantation targeted consistent sensor placement within the pulmonary artery under fluoroscopic guidance. Ultrasound-guided cannulation was used for both access routes, with tailored modifications:

Internal Jugular (IJ) Access

The right internal jugular vein was accessed under real-time ultrasound guidance to ensure precise venipuncture and minimize complications. A 90 cm Pinnacle Destination sheath (Terumo Interventional Systems) was selected for its optimal length, providing stable and reliable access from the IJ vein to the pulmonary artery. A modified Seldinger technique was employed, involving guidewire insertion through the punctured vein, followed by advancement of the sheath and delivery catheter over the wire under fluoroscopic guidance to facilitate accurate catheter navigation and sensor deployment in the pulmonary artery. Hemostasis was achieved using manual compression with a pressure dressing, ensuring secure closure and minimizing post-procedural complications.

Femoral Vein (FV) Access

The femoral vein was accessed using standard ultrasound guidance, with a 45 cm introducer sheath (eg, TorqVue [Abbott]) to accommodate the femoral route. The standard CardioMEMS implantation guide was followed, including fluoroscopic visualization for pulmonary artery placement. Closure was performed using a vascular closure device (eg, Perclose ProGlide [Abbott]), ensuring hemostasis and reducing the risk of hematoma formation.

We collected demographic and procedural data, including procedure time, contrast volume, and complications. Patients were followed for a median duration of 12 months (interquartile range [IQR]: 9-18 months) post implantation, with scheduled clinical reviews and remote monitoring assessments at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. Study outcomes were categorized into primary and secondary endpoints. The primary outcome was successful CardioMEMS implantation without major complications such as vascular injury, device malfunction, or the need for surgical intervention during the procedure. Secondary outcomes included access-site complications (eg, hematoma, infection, or bleeding requiring intervention), 30-day and 6-month readmission rates due to heart failure exacerbation, procedural times, contrast volume used, and patient-reported comfort during the recovery period.

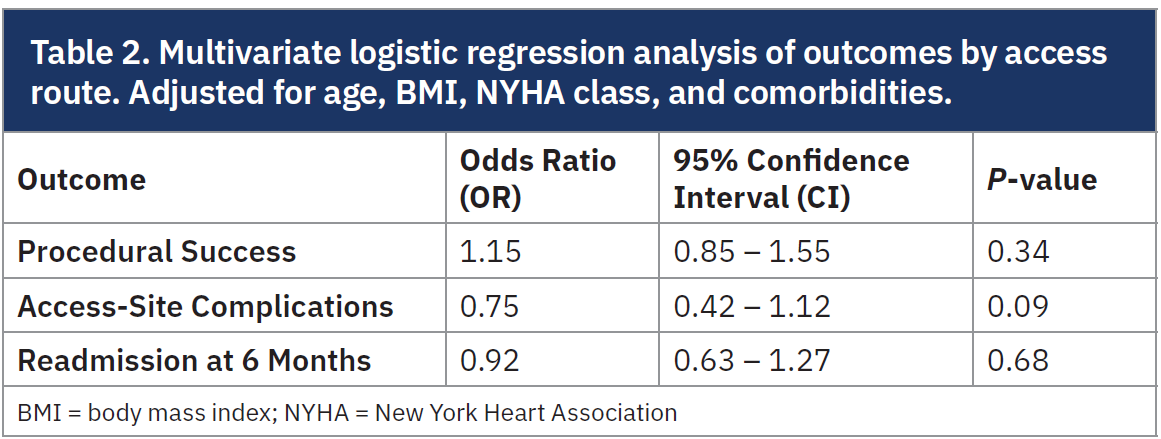

Outcomes were analyzed using descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, and t-tests. Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed for time-to-event data, with statistical significance set at P<.05 (SigmaStat v4.0 [Inpixon]). To evaluate the impact of access site (IJ vs FV) on key outcomes such as procedural success, complication rates, and readmission likelihood, we conducted multivariate logistic regression analysis, adjusting for potential confounders, including age, body mass index, NYHA class, and comorbidities. Kaplan-Meier analysis was also used to assess time-to-event outcomes for readmission and complication-free survival, with log-rank tests applied to compare survival curves between the two groups.

The study was IRB-approved (Approval No. 0833-22-FB), with informed consent obtained from all participants.

Results

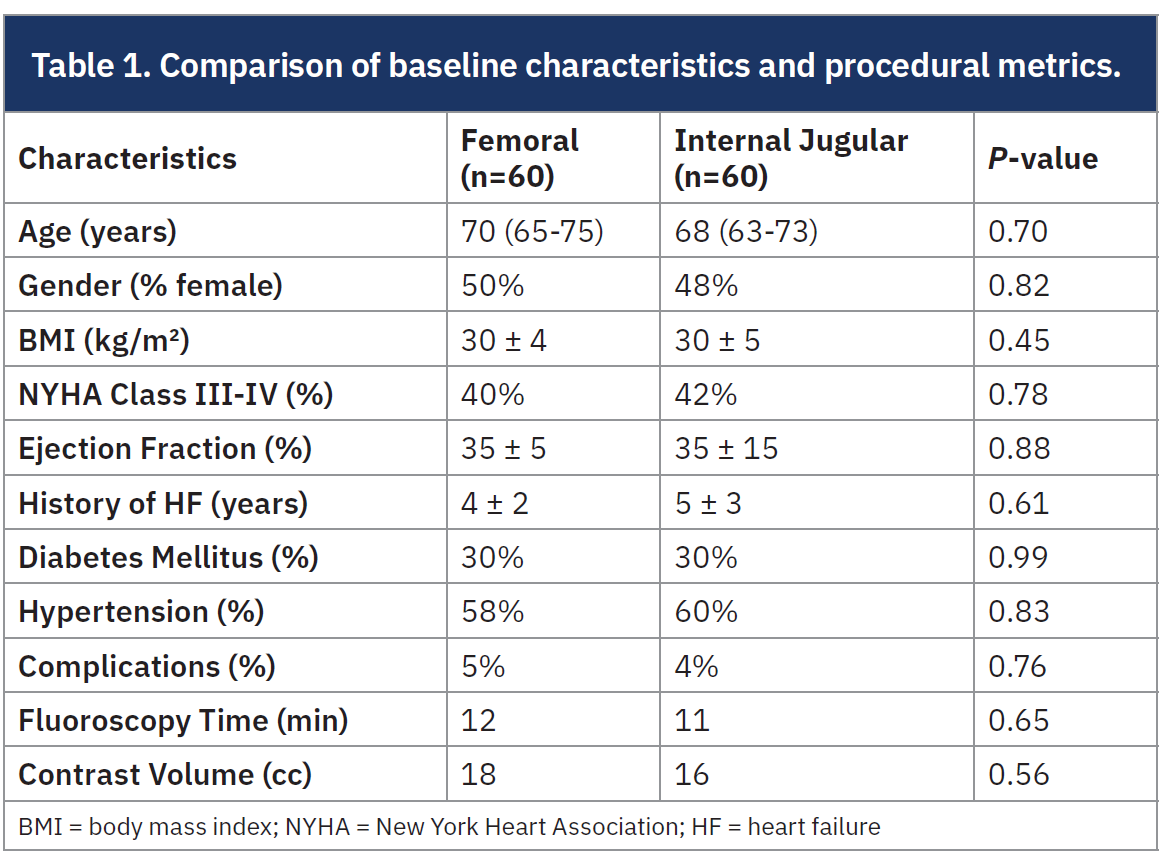

This retrospective analysis included 120 patients, split equally between internal jugular (IJ) and femoral vein (FV) access groups with comparable baseline characteristics.

This retrospective analysis included 120 patients, split equally between internal jugular (IJ) and femoral vein (FV) access groups with comparable baseline characteristics.

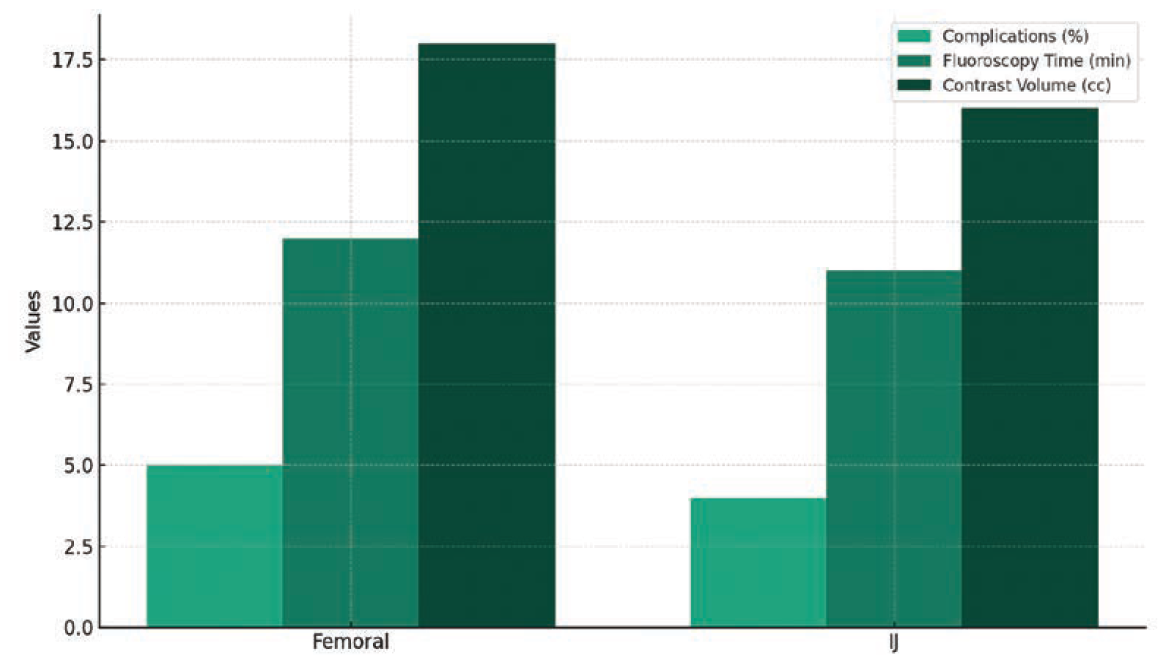

Procedural times and contrast volumes were similar between groups, averaging 55 ± 10 minutes for IJ and 58 ± 12 minutes for FV (P=.25), with contrast volumes of 18 ± 5 ml for IJ and 20 ± 5 ml for FV (P=.30). Post-procedural surveys indicated higher comfort and faster ambulation in the IJ group (Table 1).

Complications were minimal. The IJ group had one minor hematoma, while the FV group had two cases of access-site bleeding requiring intervention. The femoral access-site hematomas were managed with manual compression followed by the application of a pressure dressing for 24 hours. No vascular closure devices were used, and both patients required an additional 24-hour hospital observation period to monitor for bleeding recurrence or vascular compromise, with no further complications noted. No major complications occurred, suggesting that both access routes are safe, with a potential safety advantage for IJ access.

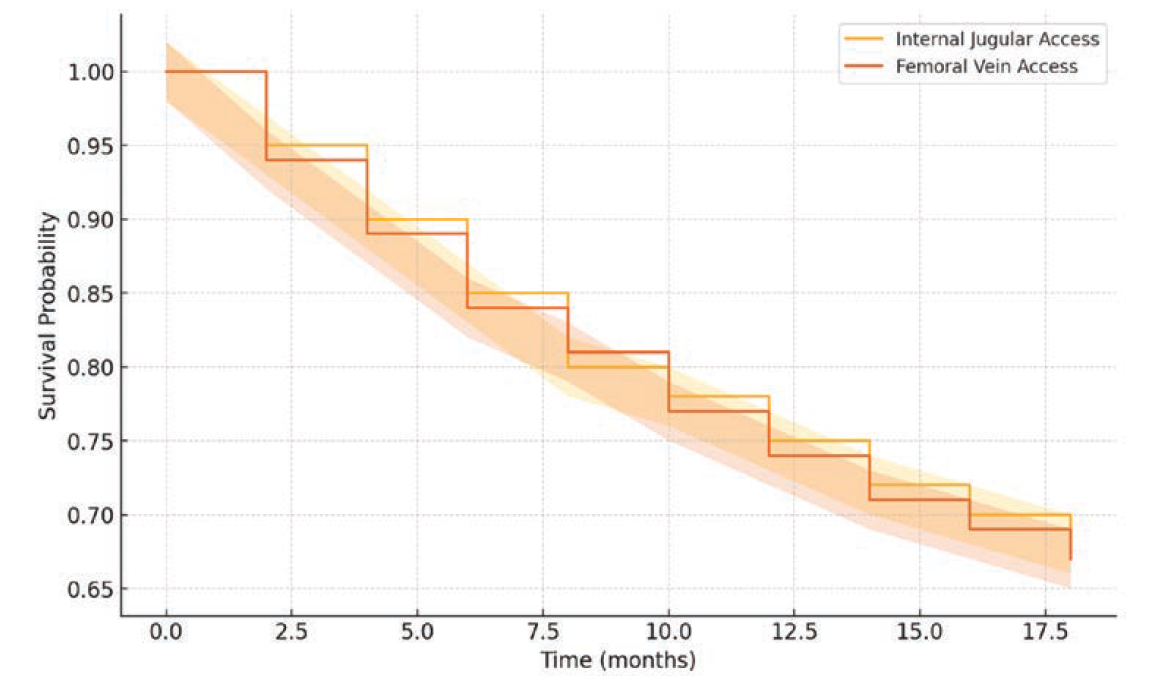

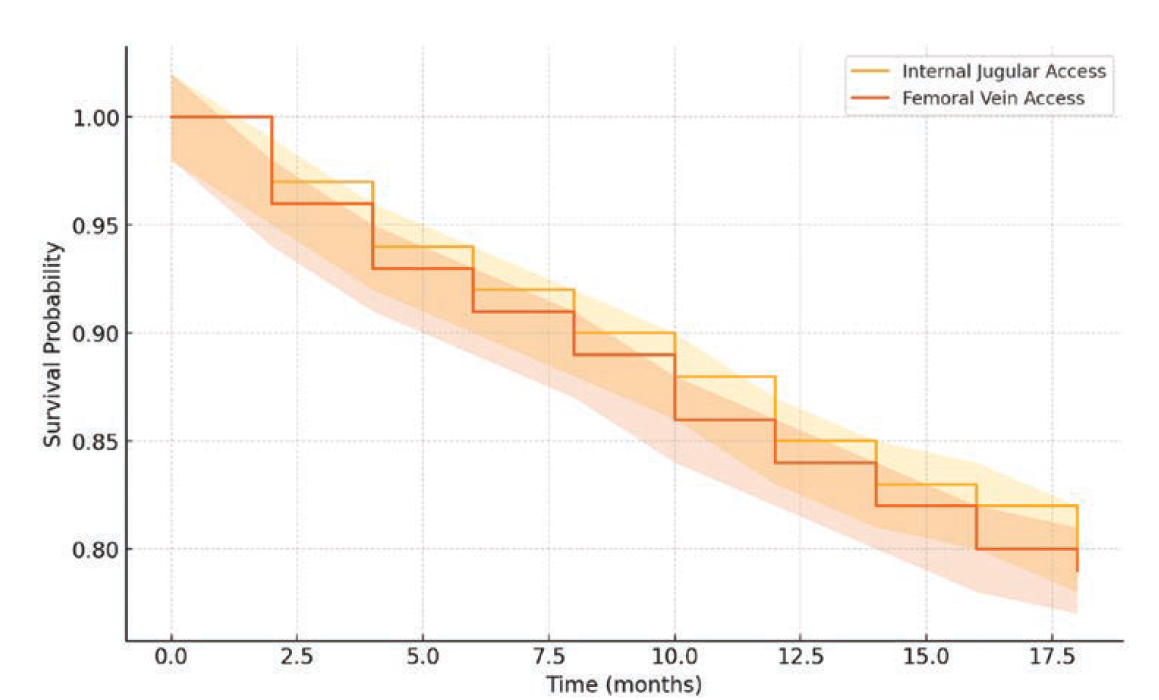

Readmission rates for heart failure exacerbation were similar (IJ: 15%, FV: 17%, P=.76). Logistic regression and Kaplan-Meier analyses showed no significant differences in readmission timing or complication likelihood between groups (Table 2). Kaplan-Meier survival curves for time to first readmission and complication-free survival are shown in Figures 2 and 3. The median follow-up duration was 12 months (IQR: 9-18 months). No significant difference was observed in time to first readmission between the IJ and FV groups (log-rank P=.61). Similarly, complication-free survival was comparable (log-rank P=.78).

One FV case had sensor migration requiring adjustment, while none occurred in the IJ group. Data transmission reliability and sensor performance were high in both groups, with minimal sensor drift (average <0.5 mmHg over six months) (Figure 1).

These findings support the feasibility and safety of both access routes, with IJ access offering potential advantages in comfort and minor complication reduction, validating it as a viable alternative to femoral access.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that internal jugular (IJ) vein access is a viable alternative to femoral vein (FV) access for CardioMEMS implantation, offering similar efficacy and safety profiles.8 The IJ approach may provide specific advantages, including a lower risk of access-site bleeding and infection, and enhanced patient comfort, particularly in outpatient settings, aligning with the growing preference for non-femoral access routes in cardiac procedures.9

These findings add to evidence supporting alternative venous access routes that reduce procedural complications. The IJ route may be especially beneficial for patients with complex vascular anatomy or obesity, where FV access is challenging.3 Additionally, the direct IJ trajectory to the right atrium may simplify catheter navigation and reduce procedural time.

While IJ access offers procedural benefits, it requires specific expertise due to risks like carotid artery puncture.10 Our use of ultrasound guidance minimized these risks, highlighting the need for proper training.11 Although direct economic analyses comparing internal jugular and femoral vein access for CardioMEMS implantation are lacking, procedural benefits associated with IJ access such as reduced fluoroscopy time, lower contrast usage, and a higher likelihood of same-day discharge, may suggest potential cost advantages. Further studies are needed to confirm the cost-effectiveness of IJ access in this context.

Limitations

This retrospective, single-center study may be subject to selection bias, as the choice of access route was based on clinician discretion and influenced by patient-specific factors. While our sample size offers valuable preliminary insights, it may not fully capture the range of possible complications, and the relatively short follow-up period limits our ability to assess long-term outcomes. Additionally, operator expertise, which can significantly impact procedural success and complication rates, was not controlled for in this study.

Conclusion

The results of this retrospective, single-center study demonstrate that internal jugular access for CardioMEMS implantation may be a reasonable alternative to femoral access, with comparable procedural outcomes and safety profiles. Observed differences in comfort and minor complications favoring the IJ route warrant further investigation. These results highlight the potential role of alternative venous access strategies in real-world practice and provide preliminary support for the use of IJ access in appropriately selected patients. Larger, prospective studies are needed to confirm these observations and guide access site selection.

References

1. Gronda E, Vanoli E, Zorzi A, Corrado D. CardioMEMS, the real progress in heart failure home monitoring. Heart Fail Rev. 2020 Jan; 25(1): 93-98. doi:10.1007/s10741-019-09840-y

2. Abraham WT, Adamson PB, Bourge RC, et al; CHAMPION Trial Study Group. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011 Feb 19; 377(9766): 658-666. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60101-3

3. Abraham J, McCann P, Wang L, et al. Internal jugular vein as alternative access for implantation of a wireless pulmonary artery pressure sensor. Circ Heart Fail. 2019 Aug; 12(8): e006060. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.119.006060

4. Kolluri R, Fowler B, Nandish S. Vascular access complications: diagnosis and management. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2013 Apr; 15(2): 173-187. doi:10.1007/s11936-013-0227-8

5. Moayedi S, Witting M, Pirotte M. Safety and efficacy of the “easy internal jugular (IJ)”: an approach to difficult intravenous access. J Emerg Med. 2016 Dec; 51(6): 636-642. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.07.001

6. Shelton CL, Mort MM, Smith AF. Techniques, advantages, and pitfalls of ultrasound-guided internal jugular cannulation: a qualitative study. Journal of the Association of Vascular Access 2016; 21: 149-156. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1552885516300678

7. Albulushi A, Al-Riyami MB, Al-Rawahi N, Al-Mukhaini M. Effectiveness of mechanical circulatory support devices in reversing pulmonary hypertension among heart transplant candidates: A systematic review. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2024 Jul; 49(7): 102579. doi:10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2024.102579

8. Lewis RS, Wang L, Spinelli KJ, et al. Right internal jugular access is an alternative to femoral access for CardioMEMS implantation. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2017; 36(4): S215. https://www.jhltonline.org/article/S1053-2498(17)30592-2/abstract

9. Pandey N, Chittams JL, Trerotola SO. Outpatient placement of subcutaneous venous access ports reduces the rate of infection and dehiscence compared with inpatient placement. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013 Jun; 24(6): 849-854. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2013.02.012

10. Storm ES, Miller DL, Hoover LJ, Georgia JD, et al. Radiation doses from venous access procedures. Radiology. 2006 Mar; 238(3): 1044-1050. doi:10.1148/radiol.2382042070

11. Moist LM, Lee TC, Lok CE, et al. Education in vascular access. Semin Dial. 2013 Mar-Apr; 26(2): 148-153. doi:10.1111/sdi.12055