The Lorraine and Bill Dodero Limb Preservation Center at University Hospitals Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Cath Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Mehdi Shishehbor, DO, MPH, PhD

President, University Hospitals Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute; Angela and James Hambrick Chair in Innovation at University Hospitals Cleveland, Ohio

Disclosure: Dr. Shishehbor reports he is a consultant to Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Terumo, Philips, Inari, Inquis, and ANT.

Mehdi Shishehbor, DO, MPH, PhD, can be contacted at mehdi.shishehbor@uhhospitals.org

Tell us about the recent $5 million gift from Lorraine and Bill Dodero, and your plans for the new Limb Preservation Center.

Tell us about the recent $5 million gift from Lorraine and Bill Dodero, and your plans for the new Limb Preservation Center.

This generous gift is the culmination of more than 20 years of dreaming and planning. My life’s work has been dedicated to caring for patients at risk of amputation, those with diabetes and vascular disease who face the devastating possibility of losing a leg. We have made meaningful progress over the years, but what we needed was a transformative investment to truly elevate the level of care we can provide.

The Dodero gift will not go toward bricks and mortar, but will directly support patient care, research, education, innovation, and public awareness around preventing amputation. It will have a profound impact and allow us to implement critical programs we have long envisioned.

One of the most difficult challenges we face is the complexity of this patient population. Unlike coronary artery disease, which can often be resolved with a bypass or stent, chronic limb-threatening ischemia doesn’t have a single fix. These wounds can take months to heal, and without ongoing management, the wounds often recur. Many of our patients have multiple comorbidities such as diabetes, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, and many are smokers or come from underserved communities. They often lack a full understanding of their condition and face barriers such as limited access to transportation, health literacy, or coordinated care.

The care these patients require is comprehensive and sustained, yet our current medical system isn’t designed or reimbursed for this level of coordination. That’s why we have used part of this gift to hire care coordinators, with plans to expand. These team members manage the full care pathway, from wound center visits and debridement to diabetes control, kidney disease management, and social needs like transportation and smoking cessation. Without this coordination, patients fall through the cracks.

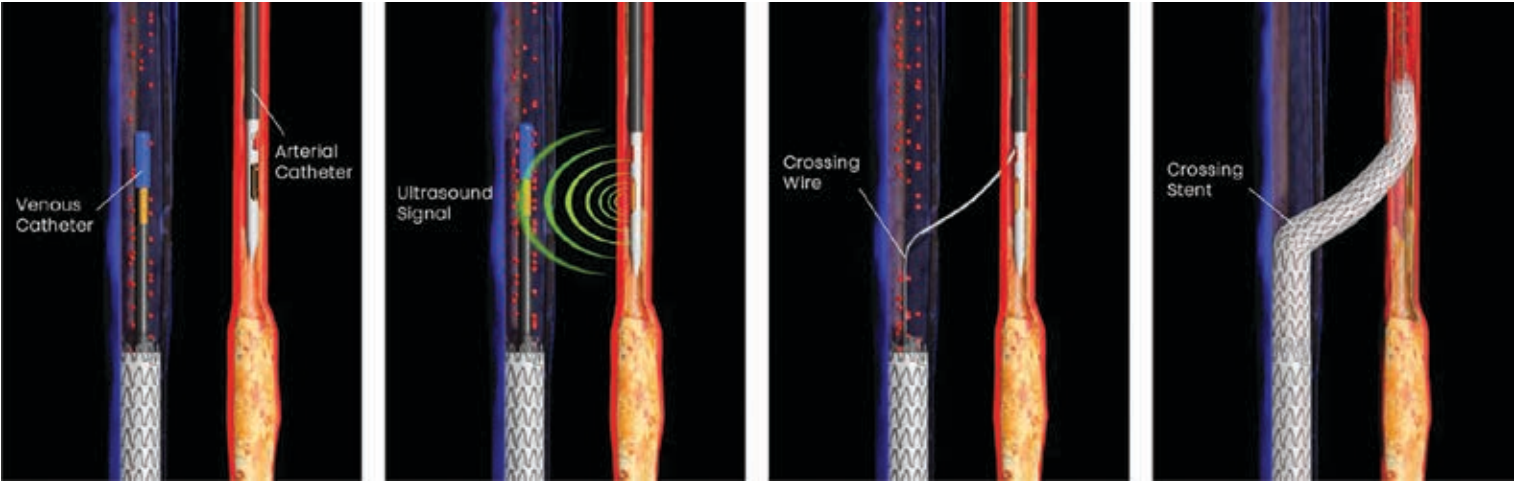

Another priority is research and innovation. Over the past decade, we have helped develop and advance the LimFlow procedure, a percutaneous bypass technique that reroutes blood from occluded arteries into healthy veins to deliver oxygen-rich blood to the foot. This was designed specifically for the 20%-30% of patients who aren’t candidates for traditional bypass or endovascular treatment. We were one of the first U.S. sites involved in LimFlow development, helped lead the clinical trials, and ultimately demonstrated that this approach could save limbs in 76% of no-option patients. Now FDA-approved and commercially available, LimFlow is changing the landscape, and this center will help us continue that momentum.

We are also developing new therapies to stimulate vessel growth in patients who lack revascularization options. It’s early, but we are optimistic, and gifts like this help fund the infrastructure, things like coordinators, research fellows, and equipment, needed to pursue cutting-edge solutions, especially as federal funding becomes harder to secure.

Education is another essential component. Having helped pioneer LimFlow, we are now training physicians from across the country. We host hands-on courses, bring visitors to our institution, and travel to train others. Our educational efforts extend beyond physicians. Many patients arrive too late, often after a prior amputation, unaware that a second opinion or limb salvage is even possible. I frequently see patients who believe losing a leg is inevitable with diabetes because that is what happened to a parent or grandparent. We want to change that narrative by raising public awareness and encouraging patients to seek out more options.

Finally, we are committed to training the next generation of limb preservation specialists, not just in one technique, but in the full spectrum of care. Fellows who rotate through our program will leave with a comprehensive understanding of wound care, diabetes management, vascular intervention, and patient-centered care coordination. This gift supports the research, innovation, education, and the systems that bring everything together for the patients who need it most.

Can you tell me about the Limb Salvage Advisory Council (LSAC) and how that works at University Hospitals (UH)?

One of my long-standing frustrations in medicine is the mindset that “if I can’t do something, then it simply can’t be done”. It’s how many of us were trained, actually, that if your skillset doesn’t offer a solution, the assumption is that no solution exists. We don’t often learn in medical school to say, “Maybe someone else can do this better.” And unfortunately, many patients don’t know to ask for a second or third opinion, especially in the context of limb-threatening disease.

So we asked ourselves, how do we build a system where second and third opinions are automatically part of the care process, without the patient or even the physician having to ask? That led to the creation of the Limb Salvage Advisory Council, or LSAC. It is a multidisciplinary committee that is automatically triggered any time a physician recommends a major amputation, below-knee or above-knee. At that point, there is a hard stop and the case must be reviewed by the LSAC before moving forward.

The council includes vascular surgeons, interventional cardiologists, vascular medicine specialists, podiatrists, wound care experts, and sometimes plastic surgeons. We meet on a virtual platform, so you can weigh in from anywhere, even if you are on vacation or across the globe. We present the case, discuss it as a team, and determine if any other options exist.

Honestly, I was surprised by the results. I thought maybe we would be able to offer alternatives to amputation in 20% or 30% of cases. We have advanced techniques and a very experienced team. But it turns out that nearly 80% of patients referred for major amputation were able to have their limbs salvaged through the LSAC process. We published our findings,1 and the impact has been enormous.

More importantly, LSAC has changed our institutional culture. It’s helped us break through the silos that still exist in medicine, between surgeons and medical doctors, between departments and divisions. In many ways, medicine isn’t naturally structured to be patient-centered, but this program forces that perspective. Everyone, regardless of specialty, comes together with one shared goal: saving the patient’s limb.

And something powerful happens when that kind of collaboration becomes the norm. Physicians begin to see the results. Patients who would have lost their leg are now walking. And once physicians witness those outcomes, they don’t need convincing anymore. They begin to believe in the process, and they start asking for LSAC reviews. What started as a requirement has now become second nature.

Just this week, we held an LSAC meeting to review two complex cases. One of our surgeons brought them forward. After discussion, we collectively decided not to proceed with amputation and to try alternative limb-salvage techniques. That’s the power of this program. It brings people together to rethink what’s possible and to give patients a fighting chance.

Once those patients reach the LSAC and then the decisions are made about their care going forward, what do you tend to see?

I would estimate about two-thirds of cases end up being endovascular. These are typically patients with severe distal disease, what we call a “desert foot”, and they often don’t have viable targets for bypass. Some cases become hybrid approaches. For example, the vascular surgeon may address the common femoral surgically, while we treat the tibials percutaneously. Or we might combine traditional revascularization with LimFlow. LSAC gives us the flexibility and environment to think creatively.

Even in hospitals where specialists work well together, things still happen in silos. Let’s say I try an endovascular approach and fail. Traditionally, I’d refer to surgery, and the surgeon might make an amputation decision independently. But in LSAC, you’ve got 10, 12, sometimes 14 people from different specialties on the same call. And suddenly someone says, “What if we go hybrid? You do this part, I do that, and the wound care specialist adds this.” It becomes a team brainstorming session, and we often realize that if each of us gives 20% or 30%, together we might actually save the leg. We are not always successful, but even when we are not, we learn. That experience shapes how we approach the next patient.

So to answer your question directly, about one-third of LSAC-driven decisions are surgical. The remaining two-thirds are either endovascular or hybrid, mostly because these patients are ineligible for bypass, which is why they were heading toward amputation in the first place.

If a health system wanted to start something similar, would the first step be obtaining buy-in from the physicians doing the amputation?

That’s right. It has to start with a cultural shift. In the beginning, not everyone was on board. We had a few physicians who didn’t support the idea and ultimately chose to leave. They believed multidisciplinary collaboration wouldn’t work and felt they alone were best equipped to care for these patients. But that didn’t reflect the values or vision of our Heart and Vascular Institute. We wanted care to be centered on the patient, not a specialty or department, and most of our team, about 90%, aligned with that. So the first step is getting physicians to agree that this isn’t about turf or titles. It’s about saving lives and limbs. Everyone has something to offer, and when we come together, we can do something special.

Then comes implementation, which isn’t always easy. You need a dedicated coordinator, someone who can manage the logistics, track referrals, gather patient data, and set up the multidisciplinary meetings. Without that structure, the whole thing falls apart. It can’t just be informal or rely on someone’s spare time. Someone needs to identify patients scheduled for major amputation, gather their medical history, imaging, wound data, and then present it to the team.

At our center, sometimes it’s a resident or fellow who does this. Other times, especially at locations without trainees, the attending physician steps in. And the presentation doesn’t need to be elaborate. There’s no slide deck, nothing fancy. We just pull up the scans, look at the records, and talk it through. It’s simple and efficient. Once we’ve had the discussion, we document the consensus in the chart, and whoever is taking the next step, whether surgical or endovascular, takes ownership from there. When it is surgical, it usually involves one of our senior surgeons, because by the time it gets to LSAC, the case is complex and requires experience.

Interestingly, one of the most unexpected benefits of LSAC has been how supportive it is for junior faculty. That wasn’t the original intention, but it has turned out to be incredibly helpful. Early-career physicians often worry about how they’re perceived, whether people will think they are not capable or confident if they refer a case they could not complete. But LSAC removes that pressure entirely. Everyone, regardless of experience level, must present complex cases being considered for amputation. It becomes the norm, not a sign of failure.

I’ve had junior colleagues present cases where I saw a potential solution and invited them to do the case together. They learned something, I learned something, and most importantly, the patient benefited. That is the culture we want to build, one where collaboration is expected and nobody has to go it alone. Whether you have been doing this for two years or 25, we all bring something to the table, and the LSAC model ensures the patient gets the best of that collective expertise.

Being able to save a patient’s limb sounds gratifying and very motivating to continue driving this work.

It’s funny because I still get emotional and excited talking about it. There’s just so much to do and so much opportunity to make a real impact. I am incredibly grateful to be part of this work. The gratitude from patients is hard to describe, and the satisfaction of saving a limb is unlike anything else.

As a cardiologist, I have done my share of STEMIs, and those are rewarding, but the interaction is intense and brief, maybe 45 minutes to an hour and a half. Limb salvage, on the other hand, is a long-term relationship. These patients often have wounds for six months, sometimes a year, and we follow them closely for months and even years after healing. It’s not a one-and-done kind of care. So when they come into clinic walking, months or years later, and they hug me and we celebrate that progress together, it’s a good feeling.

Reference

1. Shishehbor MH, Hammad TA, Rhone TJ, et al. Impact of interdisciplinary system-wide limb salvage advisory council on lower extremity major amputation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022 Jan;15(1):e011306. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.011306