A Vagal Response Is Not Always Benign: A Case of Transient ST Elevation and Hypotension in a Patient With Normal Coronary Angiography During Cardiac Catheterization

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Cath Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Morton J. Kern, MD, MSCAI, FACC, FAHA

Clinical Editor; Interventional Cardiologist, Long Beach VA Medical Center, Long Beach, California; Professor of Medicine, University of California, Irvine Medical Center, Orange, California

Disclosures: Dr. Morton Kern reports he is a consultant for Abiomed, Abbott Vascular, Philips, ACIST Medical, and Opsens Inc.

Dr. Kern can be contacted at mortonkern2007@gmail.com

On X @MortonKern

Most cardiac catheterizations for coronary angiography are safe and routine. Rare are instances of dissection, arrhythmias, infarctions, perforations, or bleeding. Vagal responses are rare and can be quickly treated by removing the painful stimulus or emptying a full bladder.1 Atropine and fluids often suffice to return the patient to the status quo. However, vagal responses, while mostly benign, should never be neglected or overlooked as unimportant, or worse, ignored until a real disaster is present. Such could have been the case with the patient we worked with recently.

Patient Presentation

Our patient was a 71-year-old man who presented with progressive exertional dyspnea and was referred for cardiac catheterization due to a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% with global hypokinesis noted on transthoracic echocardiography. He denied chest pain but described a marked decline in functional capacity over the preceding weeks. The patient had hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and obesity. He was 5 feet 3 inches tall and weighed 260 pounds (BMI ≈ 46), complicating vascular access.

Our patient was a 71-year-old man who presented with progressive exertional dyspnea and was referred for cardiac catheterization due to a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% with global hypokinesis noted on transthoracic echocardiography. He denied chest pain but described a marked decline in functional capacity over the preceding weeks. The patient had hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and obesity. He was 5 feet 3 inches tall and weighed 260 pounds (BMI ≈ 46), complicating vascular access.

Left radial access for short patients (under 5 feet 6 inches) is routine in our lab. Given his body habitus and difficulty with standard right radial access routes across the short and tortuous brachiocephalic trunk, the decision was made to proceed via left distal radial artery access, with his arm positioned across the abdomen for comfort of both the patient and the operators. It also permits working in our routine positions from the right side of the table.

The patient’s initial blood pressure before inserting the catheters was about 100/70 mmHg. 200 ml normal saline was running in during the beginning of the case. Initial diagnostic coronary angiography was performed using a 5 French TIG catheter (Terumo Interventional Systems) without difficulty. Following the first contrast injections of the left coronary artery and while torquing the catheter to engage the right coronary artery (RCA), the patient complained of left arm pain consistent with radial/brachial artery spasm. Intravenous fentanyl and intra-arterial nitroglycerin were prepared and given. Following the administration of the vasodilator cocktail for radial painful spasm, the patient became more hypotensive and complained of lightheadedness. Another large fluid bolus was requested.

Clinical Deterioration and Electrocardiogram (ECG) Changes

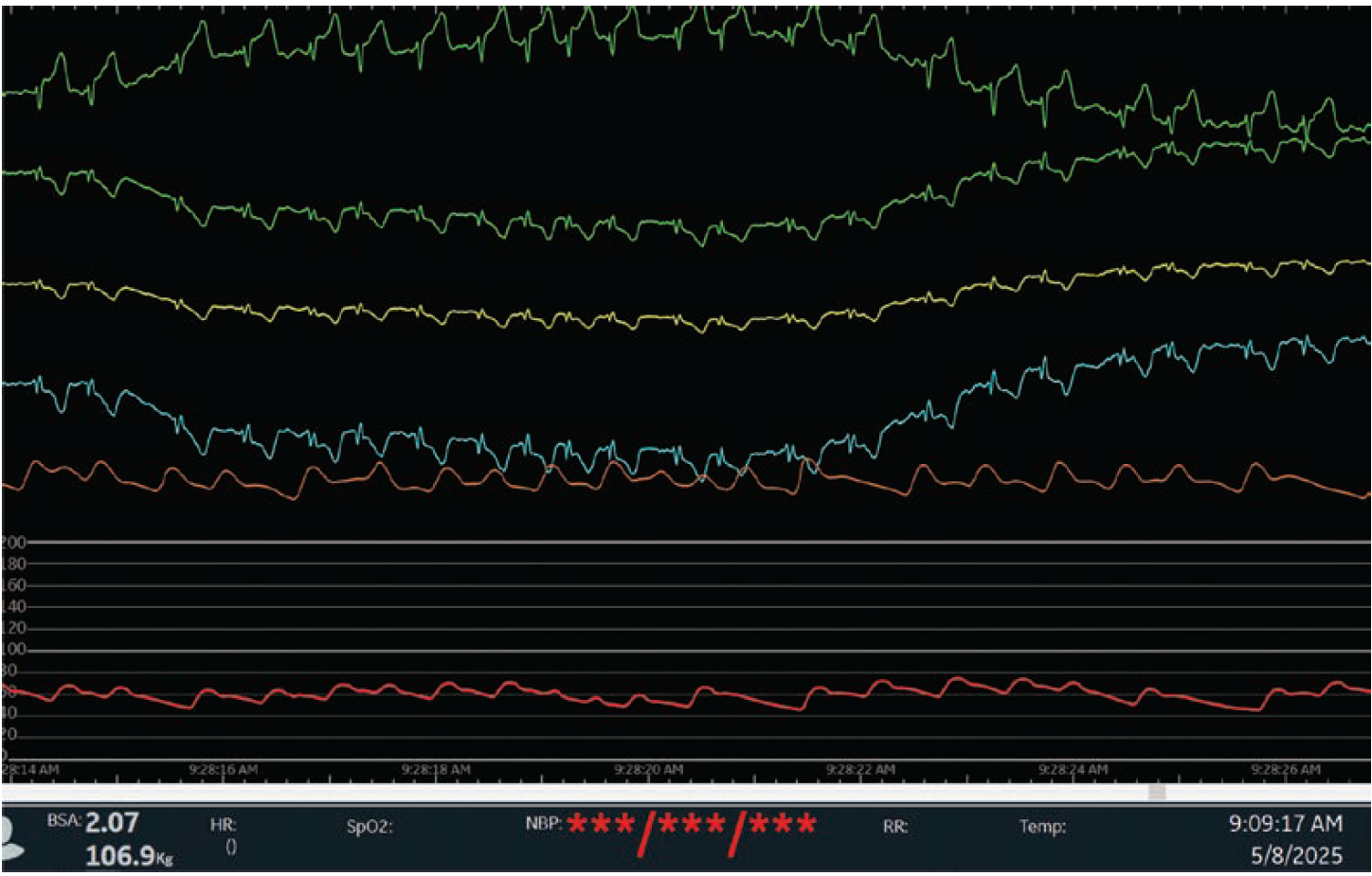

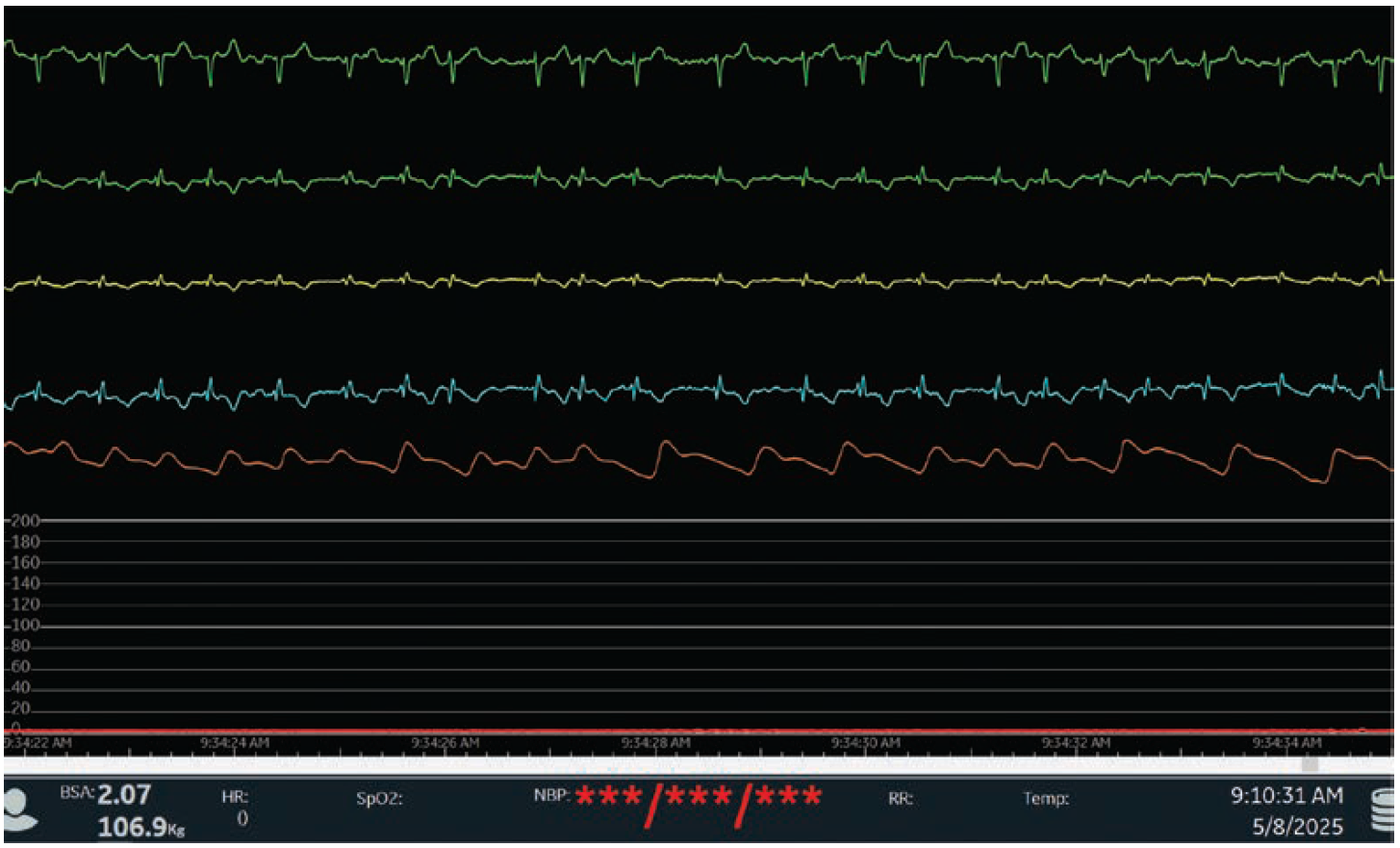

Shortly thereafter, the patient developed worsening hypotension (blood pressure 60/40 mmHg) and transient ST-segment elevation (STE) in the anterior leads (Figures 1-2) was noted. At no time did the patient have chest pain. Emergent fluid resuscitation and atropine (1.0 mg) were administered for the presumed vagal reaction. Coronary angiography was repeated to treat vasospasm if causative, but no spasm was present. Within minutes after restoration of the blood pressure (95/78 mmHg), the patient’s ST-segment elevations resolved spontaneously and returned to baseline (Figure 3).

We were surprised to see the STE come and go with the level of hypotension. No evidence of obstructive coronary artery disease, coronary dissection, or vasospasm could be found. The left and right coronary arteries were widely patent with no visible thrombus or spasm.

Discussion

This case illustrates a rare vasovagal or spasm-mediated hypotensive episode during cardiac catheterization with associated transient ST-segment elevations, possibly due to global myocardial ischemia in the setting of profound hypotension. The radial artery spasm, especially in the setting of distal access and arm positioning across the chest, likely was the inciting event leading to the patient’s discomfort, thus triggering a vagal response. The rapid resolution of hypotension and ECG changes with fluids and atropine supports this mechanism.

Vagal Effects During Cardiac Catheterization

Vagal (parasympathetic) responses during cardiac procedures — often termed vasovagal reactions — are well documented. They are typically triggered by pain or discomfort (eg, from radial artery spasm), emotional stress or anxiety, or baroreceptor stimulation (eg, from catheter manipulation).

Vagal responses can typically lead to bradycardia, hypotension due to vasomotor relaxation/dilation, nausea, lightheadedness, or syncope associated with hypotension/bradycardia and positional low cardiac output. It should be noted that in the elderly (>75 years) vasomotor-related hypotension without bradycardia can occur and be missed as a vagal reaction responsive to atropine.

The pathophysiology involves reflex activation of the vagus nerve, often due to afferent stimulation from the heart or vascular structures, which produces peripheral vasodilation and bradycardia, leading to transient hypotension. In some cases, coronary vasospasm or global myocardial hypoperfusion can result in transient ST-segment changes, even in the absence of fixed obstructive disease.

Rare Association of ST Elevation, Normal Coronary Arteries, and a Vagal Response

Rare Association of ST Elevation, Normal Coronary Arteries, and a Vagal Response

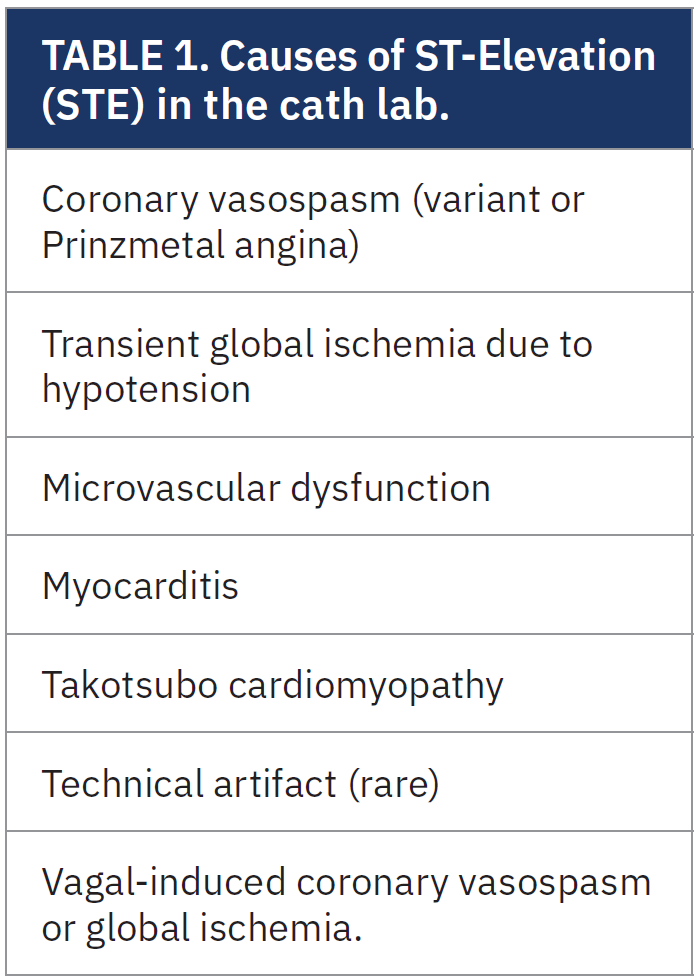

While ST elevation can often be seen during a cardiac catheterization, it is usually related to a true coronary obstruction or frank coronary vasospasm. At that time, the angiogram usually reveals the cause. It is very rare for STE to occur with normal coronary arteries without vasospasm. In the current case report, STE was attributed to subendocardial ischemia from vagally mediated hypotension and possible coronary vasospasm.

Numerous cases in the cath lab describe transient coronary spasm induced by catheter manipulation, contrast injection, or autonomic imbalance.2 Spasm often resolves with intracoronary nitroglycerin. Several other mechanisms related to STE in the cath lab are summarized in Table 1. Several reports note that pain from radial spasm, particularly during left distal access, can trigger reflex sympathetic or vagal responses. This may be exacerbated by sedation, patient positioning, or inadequate analgesia.3

Clinical Implications

Recognizing the causes of ST elevation during catheterization is critical, particularly when hypotension or bradycardia are concurrent. Once confirmed that STE is not due to coronary occlusion, avoid premature initiation of percutaneous coronary intervention, and provide supportive therapy with fluids and atropine. Reassurance (for the lab, mostly) is often helpful. Consider intracoronary vasodilators to rule out dynamic or recurrent spasm that might have been overlooked.

The Bottom Line

Transient ST elevation during catheterization with normal coronary arteries is a rare but recognized phenomenon, in this case due to vagal activation with hypotension and possible transient vasospasm. Prompt recognition of vagal physiology, especially in the context of hypotension and patient discomfort, can prevent unnecessary interventions and improve patient safety.

Moreover, in patients undergoing left distal radial access, particularly with challenging body habitus, vigilance is warranted for vascular spasm and associated hemodynamic complications. Awareness of atypical presentations of transient STE during catheterization is essential to avoid unnecessary intervention in the setting of normal coronaries.

References

1. Landau C, Lange RA, Glamann DB, Willard JE, Hillis LD. Vasovagal reactions in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Am J Cardiol. 1994 Jan 1; 73(1): 95-97. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(94)90735-8

2. Kalogeropoulos AS, Lindsay A. Preventing and treating vasovagal reactions. In: Lindsay A, Chitkara K, Di Mario C, eds. Complications of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Springer, London; 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-4959-0_1

3. Mizumaki K, Fujiki A, Tsuneda T, et al. Vagal activity modulates spontaneous augmentation of ST elevation in the daily life of patients with Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004 Jun; 15(6): 667-673. doi:10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.03601.x

Recommended Reading

1. Stewart JM, Medow MS, Sutton R, et al. Mechanisms of vasovagal syncope in the young: reduced systemic vascular resistance versus reduced cardiac output. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017 Jan 18; 6(1): e004417. doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.004417

2. Kern M. Hypotension in the cath lab? Think vagal reaction early. Cath Lab Digest. 2012 Feb; 20(2): 4-6. Accessed June 19, 2025. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/cathlab/articles/hypotension-cath-lab-think-vagal-reaction-early