Finalists From CRT’s 2025 Nurses and Technologists Interesting Cases Competition

The Cardiovascular Research Technologies (CRT) meeting was held March 8-11 in Washington, D.C.

The Cardiovascular Research Technologies (CRT) meeting was held March 8-11 in Washington, D.C.

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Cath Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Fatima Bangura, BSN, RN;

Richard Casazza, MAS, RT(R)(CI) [Presenter]; Paul Saunders, MD; Bilal Malik, MD; Robert Frankel, MD; Mazin Khalid, MD; Adnan Sadiq, MD; Arsalan Hashmi, MD; and Gregory Crooke, MD

Decima Felder, MSN, RN;

Brandy D. Smith, BS, RCIS, LMRT

At its 2025 meeting, CRT continued a new tradition that began in 2024 — a competition focused on cases submitted by nurses and technologists, with four finalists asked to present their cases during CRT’s Nurses and Technologists session.

Cath Lab Digest is proud to share the featured CRT cases in this issue (listed alphabetically by first author):

• Microvascular Spasm in CMD: More Than What Meets the Scan

Fatima Bangura, BSN, RN

• Successful Treatment of Early Bioprosthetic Mitral Valve Fusion in a Patient on VA ECMO With Balloon Valvuloplasty via Direct Cannulation of Pulmonary Vein

Richard Casazza, MAS, RT(R)(CI) [Presenter]; Paul Saunders, MD; Bilal Malik, MD; Robert Frankel, MD; Mazin Khalid, MD; Adnan Sadiq, MD; Arsalan Hashmi, MD; Gregory Crooke, MD

• Hearts in Sync: The Power of Teamwork in the Cath Lab

Decima Felder, MSN, RN

• The Direct Subaortic Laceration of the Septal Membrane (DALAS) Procedure

Brandy D. Smith, BS, RCIS, LMRT

Case #1: Microvascular Spasm in Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction (CMD): More Than What Meets the Scan

Case #1: Microvascular Spasm in Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction (CMD): More Than What Meets the Scan

Fatima Bangura, BSN, RN, MedStar Southern Maryland Hospital Center, Clinton, Maryland

Fatima Bangura, BSN, RN, can be contacted at fatima.bangura2@medstar.net

A 42-year-old African-American female with a past medical history of diabetes mellitus, depression, anxiety, and recent intentional weight loss presented with ongoing chest pain. The patient was recently evaluated at an urgent care center where a 12-lead electrocardiogram and chest x-ray were unremarkable. In the cardiology clinic, the patient reported ongoing chest pain. A prior left heart catheterization performed 3 years prior revealed insignificant coronary artery disease. The patient also had undergone transthoracic echocardiogram with a documented ejection fraction of 60% and a Zio Patch (iRhythm Technologies) that revealed no significant arrythmias. The patient was referred to MedStar Southern Maryland Hospital Center, one of the region’s only coronary functional testing (CFT) centers, for formal evaluation by interventional cardiologist Dr. Brian Case.

When reviewing coronary anatomy, it is important to consider that standard angiography only assesses the epicardial arteries, the heart’s large vessels. The microvasculature, which is the vast network of smaller vessels not seen in angiography, contributes largely to the overall blood supply of the heart. To fully assess the microvascular system, CFT is completed in two parts.

The first part includes acetylcholine provocative testing, which is a coronary vasoreactivity testing for endothelial-dependent vasomotor function. This is performed by gradual, increasing injections of acetylcholine for over 1 minute through a guide catheter and is slowly flushed with 5ml of normal saline. During administration of acetylcholine (ACh), the patient is monitored for chest pain and ischemic rhythm changes. After each infusion, a coronary cine angiography is performed to evaluate for epicardial vasospasm or slow flow suggestive of microvascular spasm. For diagnostic purposes, chest pain and/or ischemic electrocardiogram (EKG) changes during ACh infusion without epicardial vasospasm is microvascular vasospasm. Chest pain, ischemic EKG changes, and greater than 90% epicardial vasospasm on angiography is coronary vasospasm.

The second part of CFT includes performing an invasive physiological coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) assessment. This involves using a bolus thermodilution measurement technique and a PressureWire X guidewire (Abbott) to measure coronary flow reserve (CFR) and index of microvasculature resistance (IMR). The CFR refers to the resistance throughout the coronary tree, while the IMR refers to the resistance in the microvasculature. Normal CFR values are between 2.0-2.5, and the IMR should be less than 25.

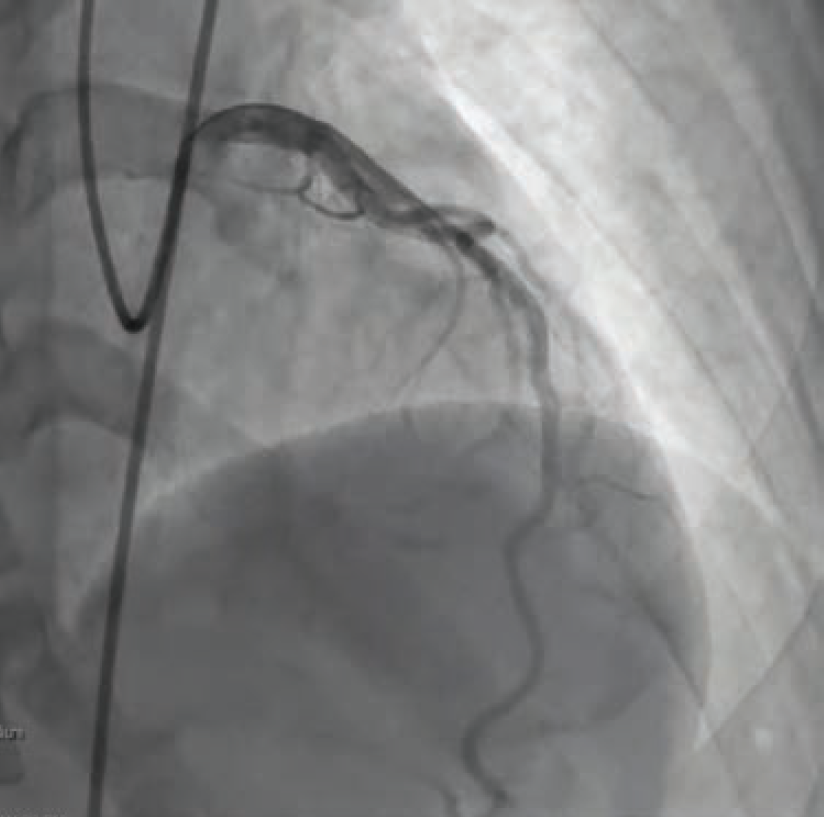

For our patient’s CFT analysis, a coronary angiogram was performed and regarding epicardial disease, demonstrated unchanged results from the previous angiogram (Figure 1). Next, we confirmed a negative invasive functional test for CMD (Figure 2). However, because the patient developed chest pain and demonstrated ST changes on electrocardiogram during ACh provocative testing, without epicardial spasm, her assessment was positive for microvascular vasospastic angina.

As a result, Dr. Case recommended isosorbide mononitrate extended release (Imdur-ER) 30 mg daily, with increasing doses as tolerated, if the patient remained symptomatic. Other recommendations for the treatment of microvascular vasospastic angina include consideration of adding calcium channel blockers, if needed. Fortunately, the patient has remained asymptomatic since her diagnosis, with initial treatment of oral nitrate.

A definitive diagnosis of microvascular vasospastic angina, confirmed by coronary functional testing, allowed this patient to achieve relief of her longstanding chest pain symptoms. Performing this testing improved this patient’s quality of life and improved her trust in the healthcare system by offering validation of her symptoms as a true medical condition. The benefit of CFT is immeasurable, as it provides critical, meaningful information for both patients and healthcare providers to improve overall coronary health and quality of life.

Case #2: Successful Treatment of Early Bioprosthetic Mitral Valve Fusion in a Patient on VA ECMO With Balloon Valvuloplasty via Direct Cannulation of Pulmonary Vein

Case #2: Successful Treatment of Early Bioprosthetic Mitral Valve Fusion in a Patient on VA ECMO With Balloon Valvuloplasty via Direct Cannulation of Pulmonary Vein

Richard Casazza, MAS, RT(R)(CI); Paul Saunders, MD; Bilal Malik, MD; Robert Frankel, MD; Mazin Khalid, MD; Adnan Sadiq, MD; Arsalan Hashmi, MD; Gregory Crooke, MD, Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, New York.

The authors can be contacted via Richard Casazza at rcasazza@maimonidesmed.org

Abstract

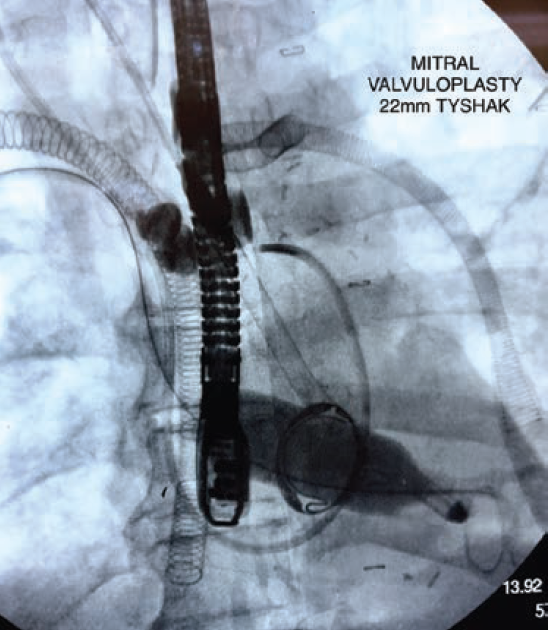

We present a case of a 57-year-old male who underwent bioprosthetic mitral valve replacement (MVR) and developed postoperative cardiogenic shock requiring venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA ECMO) and Impella 5.5 hemodynamic support. After 14 days on VA ECMO, echocardiography revealed complete fusion of the bioprosthetic mitral valve leaflets. The patient was successfully treated with balloon valvuloplasty with direct access through the right superior pulmonary vein, resulting in improvement in valve function and avoidance of repeat surgery. This case demonstrates the feasibility and efficacy of balloon valvuloplasty as a treatment option for early bioprosthetic valve dysfunction in high-risk patients.

Read the full case from Casazza et al, previously published in Cath Lab Digest’s April 2024 issue

Case #3: Hearts in Sync: The Power of Teamwork in the Cath Lab

Case #3: Hearts in Sync: The Power of Teamwork in the Cath Lab

Decima Felder, MSN, RN, MedStar Southern Maryland Hospital Center, Clinton, Maryland

Decima Felder, MSN, RN, can be contacted at decima.felder2@medstar.net

A 68-year-old male with a past medical history significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease status post percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of the proximal to distal right coronary artery (RCA) 5 years prior to presentation arrived in the Emergency Department (ED) at MedStar Southern Maryland Hospital Center by Emergency Medical Services as a Code Heart, with concerns for an inferior ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The patient reported that he was physically exerting himself at home when he suddenly started to experience crushing, substernal, and left-sided chest pain with associated lightheadedness, shortness of breath, and nausea. In the ED, patient was hypotensive and in complete heart block (CHB). The patient was evaluated by interventional cardiologist Dr. Brian Case in the ED and within 10 minutes of arrival, the patient was emergently taken to the cath lab.

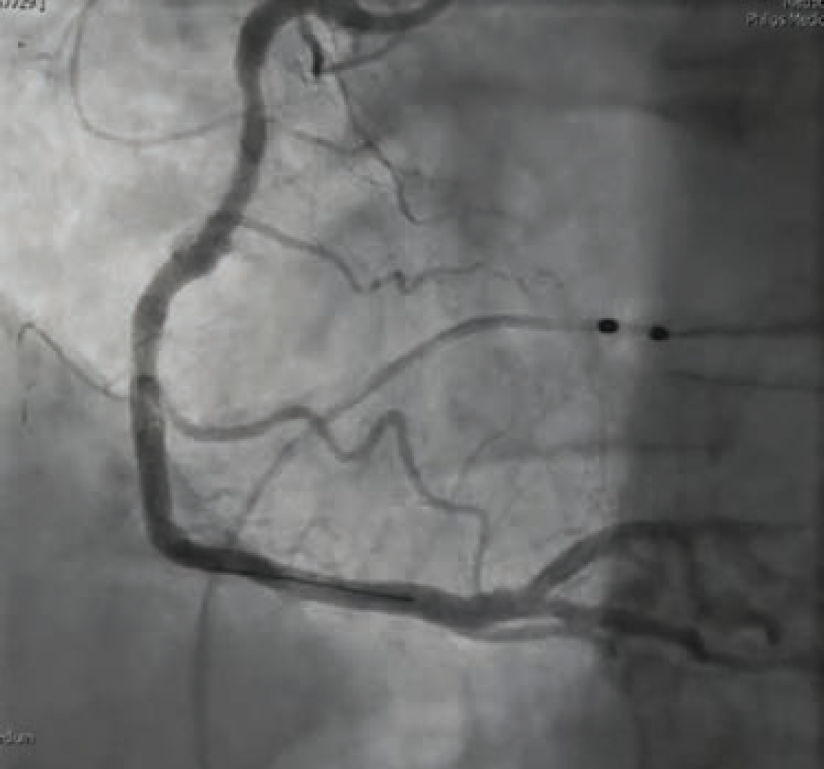

Once in the cath lab, the team of nurses and technologists worked swiftly alongside Dr. Case to first establish safe femoral access (ultrasound guidance and micropuncture technique) given the patient’s hemodynamic instability. Next, while promptly inserting a temporary venous pacemaker to address the patient’s complete heart block, the first episode of ventricular fibrillation occurred, and the first shock was successfully delivered. The team then placed an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) for cardiogenic shock management in the setting of right ventricular (RV) infarct. The operator used a 5 Fr Judkins left (JL)4 catheter to perform left coronary angiography and a 6 French hockey stick guide catheter for right coronary angiography. The patient was noted to have instent thrombosis (Figure 1), requiring mechanical aspiration thrombectomy (Penumbra). During the intervention, the patient experienced recurrent ventricular fibrillation. The cath lab team worked in unison to successfully deliver 19 shocks throughout the procedure, while administering several intravenous medications, including amiodarone, lidocaine, magnesium, bicarb, and Levophed (norepinephrine bitartrate), per the operator’s orders. Despite the critical arrhythmias and several interventions required to stabilize the patient, the team achieved a remarkable 49-minute door to balloon time in this case.

After successful thrombectomy, the delivery of a long stent was achieved by using a GuideLiner (Teleflex) guide extension catheter in the tortuous vessel. After stent placement, the patient was still having intermittent ventricular fibrillation. The Code Blue team, including intensive care unit (ICU) physicians and anesthesia, was called to be on standby for possible intubation due to recurrent arrhythmias. Fortunately, the patient remained awake, alert, and oriented (AAOx3), with oxygen saturations within normal limits on a non-rebreather. Dr. Case ballooned proximal to the stent and delivered nicardipine distally to restore flow throughout the vessel. A right heart cath was then performed to help guide management in the ICU following PCI.

Immediately following the procedure, the patient showed significant improvement in symptoms and was even cracking jokes with the cath lab team. Case findings included inferior ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), 1-vessel coronary artery disease — mid RCA 100% late stent thrombosis, complicated by ventricular fibrillation, complete heart block, and cardiogenic shock. The patient did not require mechanical support or pacemaker/implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), and remained hemodynamically stable. The patient’s cardiac rhythm stabilized and his heart function fully recovered. An echocardiogram the following day demonstrated preserved biventricular function with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 55% to 60% without wall motion defects. Troponins trended downward and he remained chest pain-free. The patient was discharged home 4 days after his initial STEMI presentation.

Conclusion

Through exceptional teamwork, a complex patient experiencing a life-threatening heart attack was quickly and effectively treated by the team at MedStar Southern Maryland Hospital Center. The coordinated efforts of the ED team upon patient arrival, and the interventional cardiologist, nurses, and technologists from the cath lab, ensured rapid preparation and immediate intervention. As a result, the patient’s life was saved, showcasing the critical importance of collaboration and efficiency in the ED and cath lab during emergencies.

Case #4: The Direct Subaortic Laceration of the Septal Membrane (DALAS) Procedure

Case #4: The Direct Subaortic Laceration of the Septal Membrane (DALAS) Procedure

Brandy D. Smith, BS, RCIS, LMRT, Baylor Scott and White The Heart Hospital and The Cardiovascular Institute, Plano, Texas

Brandy Smith, BS, RCIS, LMRT, can be contacted at brandy.smith2@bswhealth.org.

Patient Presentation and Evaluation

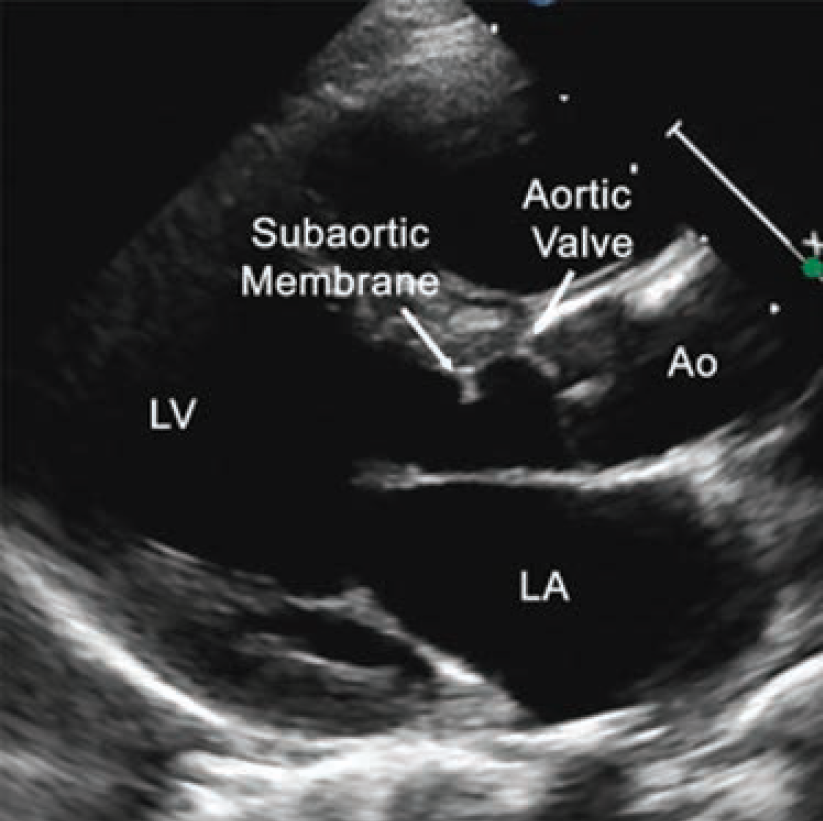

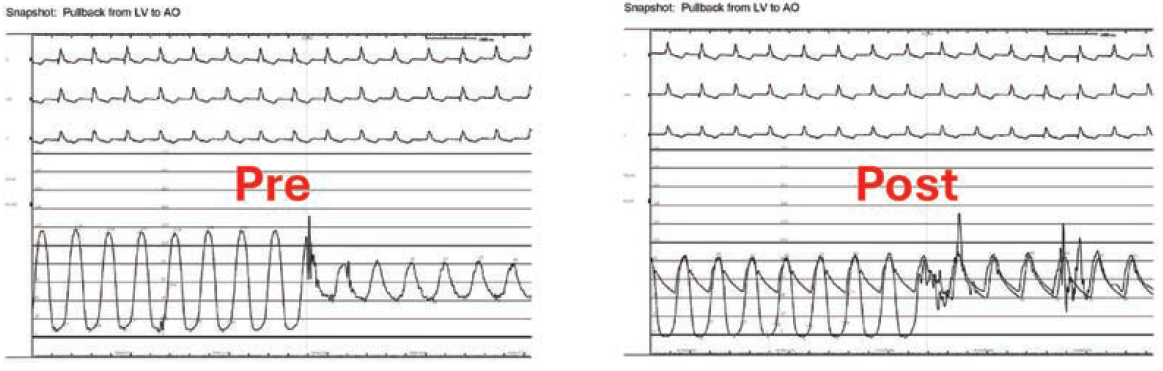

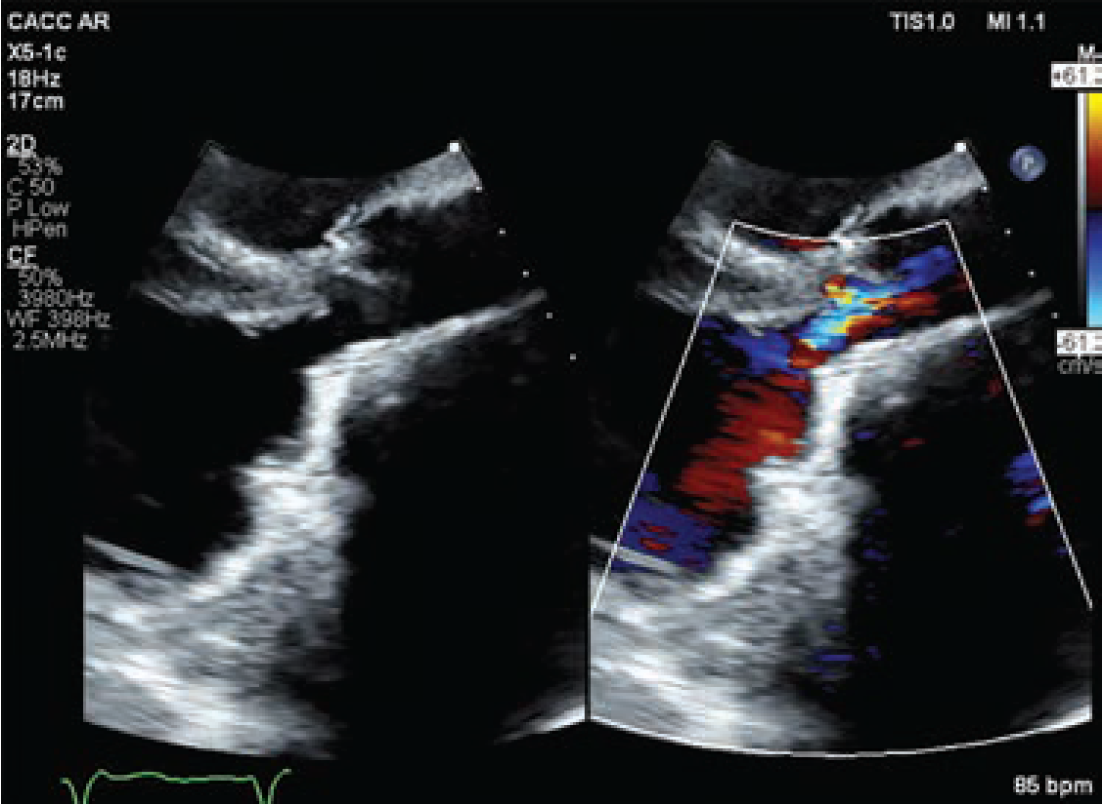

A 64-year-old female presented to the valve clinic with increasing shortness of breath, dizziness, and multiple implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shocks over 4 months. She required 2 liters of nocturnal O2 and had a fall with significant head trauma due to syncope. She was referred to the valve clinic for consideration of a percutaneous treatment option for a subaortic membrane. She was a poor surgical candidate due to three prior sternotomies from prior valve replacements. Additionally, she presented with chronic atrial fibrillation, a history of stroke, a thromboembolic disorder, and a left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) gradient of 80 mmHg. A transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) revealed that she had an ejection fraction (EF) of 20% (Figure 1). Her case was complex and high risk.

Baseline computed tomography imaging revealed the patient had an enormous left atrium (volume of 798 cm3), a narrow LVOT, and an 8.5 mm subaortic membranous band. The team determined that multimodality imaging (TEE, transthoracic echocardiogram [TTE], and intracardiac echocardiography [ICE]) would be required for an endovascular fix due to shadowing artifacts from the mechanical mitral valve and the tricuspid ring, as well as distortion from the large left atrium.

What is the DALAS Procedure?

Lessons learned from the BASILICA and SESAME procedures framed the thought process for a DALAS procedure. In a BASILICA (Bioprosthetic or Native Aortic Scallop Intentional Laceration to Prevent Iatrogenic Coronary Artery Obstruction) procedure, an aortic valve leaflet that could potentially obstruct a coronary artery during a transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is traversed with a wire and snared. Electricity is then delivered to the problematic leaflet via the snared wire, lacerating it. The SESAME (Septal Scoring Along the Midline Endocardium) procedure places a wire through the problematic portion of the septal myocardium, snares the wire in the LV, and electricity is delivered, lacerating the LVOT and relieving the obstruction. The DALAS (Direct Subaortic Laceration of the Septal Membrane) procedure uses the same principles to remove the subaortic membrane.

Patient Procedure

A VeriSight Pro ICE catheter (Philips) was placed via a 10 French (F) sheath in the left common femoral vein. The right and left common femoral arteries were accessed for the equipment needed to lacerate the membrane. A 12F steerable guide was inserted through a 16 mm x 33 mm sheath in the right common femoral artery. A 7F 90 cm MP1 catheter was inserted into the steerable guide with a Hornet 14 wire (Boston Scientific) and a 135 cm Turnpike Spiral microcatheter (Teleflex). Sixteen minutes later, the Hornet wire punctured the membranous tissue; the Turnpike was advanced over the wire, allowing the wire to be exchanged for a 300 cm Grand Slam wire (Asahi Intecc). The Turnpike was removed, and a 2.0 mm x 20 mm noncompliant (NC) balloon was inflated, followed by a 6.0 mm x 12 mm NC balloon. The balloon was removed and the Turnpike was reinserted. The guidewire was exchanged for an Astato XS 20 300 cm wire (Asahi Intecc). A Judkins right (JR)4 catheter with an EN Snare 18-30 mm (Merit Medical) was inserted into the left common femoral artery. Snaring the wire took 4 minutes (Video 1) and the wire was pulled into the JR4 catheter. High-frequency electrical energy was applied to the denuded Astato 20 wire with a Bovie, lacerating the subaortic membrane (Video 2).

Video 1. Snaring the wire.

Video 2. DALAS performed: High-frequency electrical energy was applied to the denuded Astato 20 wire with a Bovie, lacerating the subaortic membrane.

The procedure was evaluated by TEE, TTE, and ICE (Video 3), ensuring its success. These imaging modalities showed no pericardial effusion or apparent damage to the aortic valve. Further, post-procedure hemodynamics demonstrated no residual gradient (Figure 2).

Post procedure, the patient had no complications and experienced significantly improved symptoms. At her 6-week follow-up appointment, the patient was no longer short of breath, had no additional ICD discharges, no syncopal episodes, and her EF had improved to 35%-40% (Figure 3; Video 4). She was discharged to her referring out-of-state cardiologist.

Video 3. Immediately post procedure, evaluating by intracardiac echo (VeriSight Pro, Philips).

Video 4. At her 6-week follow-up appointment, the patient was no longer short of breath, had no additional ICD discharges, no syncopal episodes, and her EF had improved to 35%-40%.

Conclusion

The increasing complexity of patients in the catheterization laboratory underscores the necessity for multidisciplinary and innovative approaches to address patients’ specialized needs. As physicians expand their knowledge and master new procedures, they can leverage this expertise in new scenarios, ultimately providing enhanced patient care. This case exemplifies the effective application of acquired knowledge to resolve a challenging case, highlighting the potential for innovative solutions in patient care.

Find More:

Cardiovascular Ambulatory Surgery Centers (ASCs) Topic Center

The Latest Clinical & Industry News

Grand Rounds With Morton Kern, MD

Peripheral Artery Disease Topic Center

Podcasts: Cath Lab Conversations