Rare Case of Myocardial “Milking” in a Diagonal Branch Artery (Expanded)

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Cath Lab Digest or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Richard Casazza, MAS, RT(R)(CI); Arsalan Hashimi, MD; Nicole DeLeon, MD; Enrico Montagna, RT(R)(CI); David J. Epstein, MD

Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, New York

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial relationships or conflicts of interest regarding the content herein.

Consent statement: Informed consent from the patient was received.

The authors can be contacted via Richard Casazza at rcasazza@maimonidesmed.org; X: @tesslagra

Reprinted and expanded with permission from Casazza R, Epstein DJ, DeLeon N, Montagna E, Sarro I, Hashimi A. Rare case of myocardial milking in a diagonal branch artery. J Invasive Cardiol. 2025 Jan;37(1). doi:10.25270/jic/24.00223

Myocardial bridging is a very common anomaly, which can be found in more than 30% of the population, based on autopsy studies.1 It happens when a segment of a major epicardial coronary artery runs intramural through the myocardium. It is a common congenital anomaly sometimes referred to as a “tunneled artery.” Systolic compression during filling can result in hemodynamic changes that may be associated with angina, myocardial ischemia, acute coronary syndrome, left ventricular dysfunction, arrhythmias, and even sudden cardiac death.2

Myocardial bridging is a very common anomaly, which can be found in more than 30% of the population, based on autopsy studies.1 It happens when a segment of a major epicardial coronary artery runs intramural through the myocardium. It is a common congenital anomaly sometimes referred to as a “tunneled artery.” Systolic compression during filling can result in hemodynamic changes that may be associated with angina, myocardial ischemia, acute coronary syndrome, left ventricular dysfunction, arrhythmias, and even sudden cardiac death.2 A study found that the relative frequency of myocardial bridging exclusively involving the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery was 70%, involving the muscular loop of the left circumflex artery was 40%, and involving the right coronary artery was 36%.3 There are little data on myocardial bridging in branch vessels. Angiographically, there are various degrees of myocardial bridging; however, when a vessel completely obliterates during cardiac catheterization, it is referred to as a “milking” phenomenon.

Presentation

We present a 54-year-old female with a past medical history of opioid addiction, anxiety disorder, and who is a current cigarette smoker. She presented to the hospital via Emergency Medical Service (EMS), after having an episode of syncope at home. The patient lost consciousness while in bed, witnessed by her husband, who performed brief cardiopulmonary resuscitation, after which she regained consciousness. En route to the hospital, she had another three syncopal episodes, and was noted by EMS to have brief runs of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) each time, which self-terminated after a couple of seconds.

In the days prior to these events, the patient reported having taken extra doses of methadone. As per the patient, this episode was not the first time she had fainted; in the four years prior to admission, she claimed to have had at least seven episodes of losing consciousness, but never sought medical attention. She stated that at baseline, she is able to walk up to one mile without chest pain or dyspnea, and can climb stairs up to four floors before experiencing dyspnea.

Upon arrival to the emergency department, she continued to have persistent ectopy on telemetry and then had an episode of sustained monomorphic VT; during this episode, she did not faint but did feel palpitations. However, this arrhythmia also terminated on its own after just under one minute prior to planned cardioversion. Cardiology and electrophysiology were consulted, and she was admitted to the CICU for further care/monitoring. The patient was started on intravenous (IV) amiodarone, and later changed to a lidocaine drip, in addition to IV heparin. Magnesium and potassium were supplemented.

History

• Past medical history: prior opioid addiction (currently on methadone), remote crack cocaine use, anxiety disorder, cigarette smoking;

• Social history: Current smoker (1 pack/day for 35 years), current daily marijuana smoker, former alcohol drinker, and former heroin user (stopped 10 years prior to presentation);

• Family history: No family history of cardiovascular disease or sudden cardiac death;

• Allergies: None;

• Surgical history: Left breast cyst removal;

• Home medications: Methadone 160 mg daily, clonazepam 0.5 mg twice daily.

Review of Systems

• General [-] no anorexia, no chills, no fever, no malaise/fatigue, no weight loss;

• Neuro [-] no confusion, no memory loss, no headache, no numbness, no weakness;

• Neuro [+] fainting or loss of consciousness;

• Psych [+] anxiety;

• Respiratory [-] no wheezing, no pleuritic chest pain, no dyspnea;

• Cardiovascular [-] no lower extremity swelling, no chest pain, no claudication.

Vital Signs

Blood pressure 148/81 mmHg, heart rate 112 beats per minute (bpm), respiratory rate 25 breaths/min, SpO2 (peripheral oxygen saturation) 98% (on room air), temperature 98.8˚F

Physical Examination

• General appearance: middle-aged female, somewhat ill-appearing, in no acute distress;

• Psychiatric: Anxious;

• Neurological: Awake, alert and oriented, no focal neurological deficits noted;

• Respiratory: Chest with normal expansion, lung fields clear to auscultation bilaterally;

• Cardiovascular: Tachycardic, regular rhythm with frequent ectopic beats, S1 and S2 audible, 1/6 holosystolic murmur heard best over the apex;

• Extremities: No limb edema.

Diagnostic Tests

• EKG: Sinus rhythm at 90 bpm, normal axis, ventricular bigeminy, probable left atrial enlargement, PR 150 ms, QRS 94 ms, QT 440 ms, QTc 504 ms.

• Laboratory results: Serial cardiac troponin I: 0.87, 0.93 and 0.90 ng/mL, B-type natriuretic peptide 2388.0 pg/ml, sodium 138 mmol/L, potassium 3.2 mmol/L, magnesium 1.4 mg/dL, BUN 13 mg/dL, creatinine 1.0 mg/dL, venous pH 7.38, lactic acid 8.7 mmol/L; urine toxicology was positive for cannabinoids and methadone metabolites.

• Echocardiogram: Severely decreased left ventricular (LV) systolic function; LV ejection fraction (EF) by visual estimation was 25%. Global cardiomyopathy; apex and septum were worse. Moderate (grade 2) LV diastolic dysfunction. Elevated mean left atrial pressure. Mildly dilated LV, left atrium (LA volume index = 34.36 ml/m²), right atrium, and right ventricle (RV). Mildly reduced RV systolic function. Mildly elevated pulmonary artery systolic pressure. The inferior vena cava was dilated with respiratory size variation >50%. Mild thickening of the anterior and posterior mitral valve leaflets with mild to moderate mitral regurgitation. Mild aortic valve sclerosis without stenosis. Mild tricuspid regurgitation.

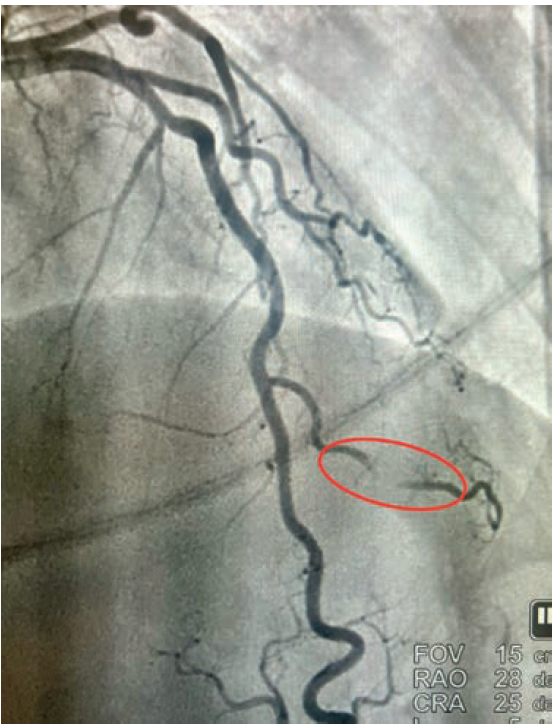

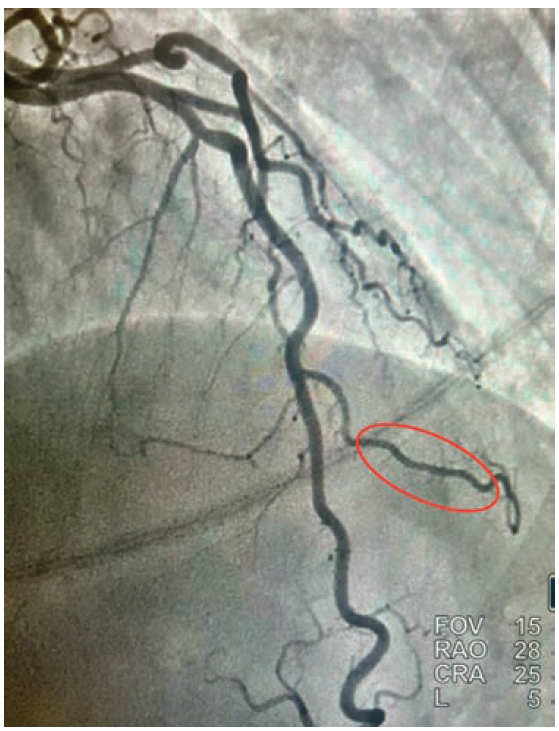

• Cardiac catheterization: Catheterization revealed normal coronary arteries with severe systolic compression of the second diagonal branch (Figures 1-2; Video).

Discussion

Given the fact that the patient continued to have recurrent episodes of ventricular tachycardia, along with elevated troponin, and an echocardiogram showing reduced LVEF with slightly more pronounced hypokinesis of the septal and apical walls, the decision was made to rule out ischemia as a possible cause. She subsequently underwent coronary angiography via right radial approach, which revealed a right-dominant system and normal coronary arteries, with the exception of the 2nd diagonal branch of the LAD, which had severe systolic compression, resulting in near-obliteration of the artery with each cardiac cycle (Video).

Our patient was referred for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) placement for cardiomyopathy. Medical therapy was recommended for the bridging. Initial treatment of myocardial bridging primarily includes beta blockers, thought to relieve hemodynamic disturbances by decreasing peak heart rate, increasing diastolic filling time, and decreasing contractility and compression of the artery.4 Certain patients who have intractable angina may need surgical intervention. “Un-roofing” myocardial bridging entails dissecting through the myocardium to uncover the tunneled artery caused by systolic compression. These operations typically involve the LAD; however, there is a paucity of data on “un-roofing” branch vessel bridging. Severe myocardial bridging, also known as “milking”, is seldom seen in branch vessels.

Reference

1. Hostiuc S, Negoi I, Rusu MC, Hostiuc M. Myocardial bridging: a meta-analysis of prevalence. J Forensic Sci. 2018;63:1176-1185. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1556-4029.13665

2. Lee MS, Chen CH. Myocardial bridging: an up-to-date review. J Invasive Cardiol. 2015 Nov; 27(11): 521-528. https://www.hmpgloballearningnetwork.com/site/jic/articles/myocardial-bridging-date-review

3. Polacek P, Kralove H. Relation of myocardial bridges and loops on the coronary arteries to coronary occlusions. Am Heart J. 1961; 61:44-52. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0002870361905154

4. Schwarz ER, Klues HG, vom Dahl J, et al. Functional, angiographic and intracoronary Doppler flow characteristics in symptomatic patients with myocardial bridging: effect of short-term intravenous beta-blocker medication. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1637-1645. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0735109796000629