What Is This Lesion on an Older Woman’s Finger?

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of the Dermatology Learning Network or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Case Report

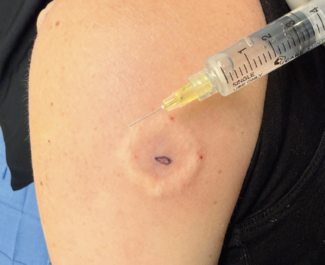

An 84-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a purple lesion on her left index finger. The patient noted symptoms of pain, bleeding, and swelling in the surrounding skin. The lesion first appeared as a blister 5 months earlier and was lanced twice but showed no signs of healing. She had no history of previous skin cancer. Physical examination of the area revealed an erythematous, friable oval nodule with evidence of recent bleeding (Figure 1). A shave biopsy was obtained.

What is your diagnosis?

Scroll below to find out!

Diagnosis

Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC)

MCC is a rare cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinoma associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV), chronic exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, and/or reduced cellular immunity.1 It is a highly aggressive tumor with a mortality rate of 33% to 46%, and nearly one third of patients present with regional or lymph node metastases.2 Although MCC tumors and Merkel cells express similar unique neuroendocrine markers, research has found that MCC does not derive from the Merkel cell. The cell of origin for MCC is still unknown, although it has been speculated that epidermal stem cells could be linked to its development.3

MCPyV likely plays a part in MCC pathogenesis. One study of 282 MCC tumors found approximately 80% of tumors testing positive for the MCPyV virus.4 MCPyV infection is present in most healthy adults and is therefore thought to be a component of the skin’s standard microbiome.5 MCC is more frequently linked to MCPyV in regions with a lower UV index.3 Current studies show that MCPyV-negative tumors may be more aggressive and are more likely to metastasize.4

Epidemiology and Clinical Presentation

MCC presents as a rapidly enlarging, asymptomatic, red-violet papule, nodule, or plaque commonly found in UV-exposed areas of the skin, particularly on the head, neck, or upper extremities.6 Some tumors, especially those associated with epithelial squamous cell carcinomas (SCC), may also be ulcerated.7 Populations at risk for MCC include patients of advanced age, immunosuppressed individuals, and those living in lower latitudes due to increased UV exposure. MCC is most common in individuals with fair skin tones, with the incidence rate being highest in non-Hispanic White men. The incidence rate in the United States ranges from 0.66 to 0.79 cases per 100,000 individuals.8

Histology

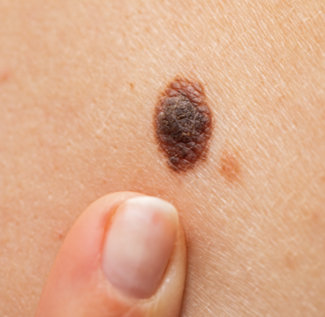

MCC cells typically appear as small, round, blue cells arranged in nodules or sheets. Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining of tumor cells shows mitotic figures, a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, and chromatin exhibiting a characteristic, finely granular “salt and pepper” pattern (Figure 2).7 Small-cell and trabecular histologic patterns have both been observed, but most cases are classified as intermediate and display characteristics of both variants.3 Because the “small, round, blue” cytomorphology also matches the microscopic appearance of other tumors, including metastatic small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC), immunohistochemical staining is required for definitive diagnosis.8

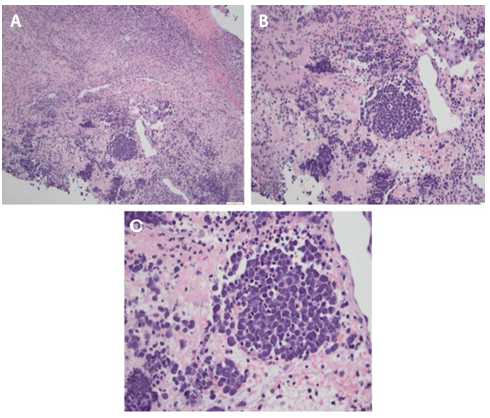

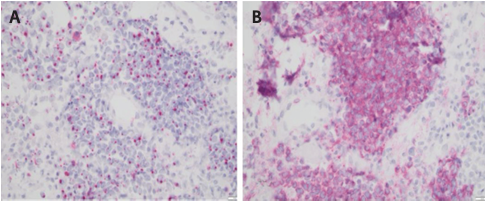

A standard marker of MCC cells is a positive cytokeratin 20 (CK20) stain, which appears in a perinuclear dot-like pattern (Figure 3A).9 SCLC cells are typically positive for cytokeratin 7 (CK7), a marker used to distinguish adenocarcinomas, and thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1), a characteristic marker of lung adenocarcinomas. Due to their neuroendocrine nature, MCC cells will typically be negative for both TTF-1 and CK7, and positive for synaptophysin (Figure 3B).10

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnoses for MCC include cyst, dermatof ibroma, amelanotic melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, SCC, atypical fibroxanthoma, and cutaneous metastasis of other tumors. Histopathologically, other tumors with small, round, blue cell morphology include lymphoma, amelanotic melanoma, neuroblastoma, Ewing sarcoma, and cutaneous metastatic SCLC.3,11

Treatment

Once a patient has a confirmed diagnosis of MCC, the sentinel lymph node basin is clinically examined for possible metastasis. If clinically positive, imaging studies and a subsequent lymphadenectomy are recommended. In cases without clinical evidence of metastasis, a sentinel lymph node biopsy should be performed. The preferred treatment for the primary cutaneous tumor is wide local excision with 1-cm to 2-cm margins. Wide local excision can also be substituted for Mohs micrographic surgery when 1-cm to 2-cm margins are not practical. This is followed by adjuvant radiotherapy to the site of the primary tumor and potentially the regional lymph nodes.3,12

After treatment is complete, it is recommended for the patient to follow up at 3- to 6-month intervals for examination, including lymph node palpation and ultrasound, for the next 3 years.12

For more advanced cases of MCC, immunotherapy has been shown to be highly effective. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, including avelumab, pembrolizumab, and nivolumab, can be used to treat advanced or metastatic MCC. Nonetheless, in some cases, MCC may not respond to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors or develop resistance to them. Immunotherapy is also contraindicated in patients with autoimmune disorders. Although MCC initially responds to chemotherapy, the response is short-lived, and the tumor rapidly becomes resistant to treatment. Thus, clinical trials investigating alternative treatments and the combination of immune-based therapies are ongoing.3,12

Our Patient

We performed a shave biopsy, which revealed neoplastic cells with rounded, finely granular nuclei and scant cytoplasm that stained positive for pan-cytokeratin and synaptophysin, indicating a malignant tumor of neuroendocrine origin. The overall immunohistochemical profile was indicated to be identical with metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma. The patient was referred to a dermatology oncology center for further evaluation, where she was recommended to have a wide local excision of the lesion and a sentinel lymph node biopsy. Given the size of the lesion and aggressive histology, adjuvant radiation was also planned post-op. The final surgical pathology after wide local excision indicated a pathologic stage pT1N1Mx tumor with one sentinel lymph node positive for MCC, indicating stage IIIA MCC.13

Conclusion

MCC is a rare, aggressive disease and its pathophysiology is not well understood. It is extensively debated whether the originating cancerous cell is even the Merkel cell.3 Therefore, diagnosis and treatment require close evaluation of a patient’s history and physical examination and the histopathology of suspicious lesions. This report highlights the importance of histologic evaluation in differentiating between skin malignancies, as the observed cell morphologies and staining results can lead to significantly differing prognoses and treatment plans.

Aaisha Jamiluddin is a medical assistant at AllPhases Dermatology, LLC in Alexandria, VA, and a medical school applicant. Vrinda Deshpande is a medical student at Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine in Richmond, VA. Dr Ebert is affiliated with Dermpath Diagnostics in Newton Square, PA. Dr Aziz is the staff attending at the Washington VA Medical Center and an assistant professor of dermatology at Howard University and George Washington University in Washington, DC, and an attending physician at AllPhases Dermatology, LLC.

Reference

1. Stockfleth E. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(5):1534-1534. doi:10.3390/cancers15051534

2. Schadendorf D, Lebbé C, zur Hausen A, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: epidemiology, prognosis, therapy and unmet medical needs. Eur J Cancer. 2017;71:53-69. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.10.022

3. Becker JC, Stang A, DeCaprio JA, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3(1):17077. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.77

4. Moshiri AS, Doumani R, Yelistratova L, et al. Polyomavirus-negative Merkel cell carcinoma: a more aggressive subtype based on analysis of 282 cases using multimodal tumor virus detection. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(4):819-827. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2016.10.028

5. Sherwani MA, Tufail S, Muzaffar AF, et al. The skin microbiome and immune system: potential target for chemoprevention? Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2017;34(1):25-34. doi:10.1111/phpp.12334

6. Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(3):375-381. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.020

7. Pulitzer MP, Amin BD, Busam KJ. Merkel cell carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16(3):135-144. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181a12f5a

8. Jaeger T, Ring J, Andres C. Histological, immunohistological, and clinical features of Merkel cell carcinoma in correlation to Merkel cell polyomavirus status. J Skin Cancer. 2012;2012:983421. doi:10.1155/2012/983421

9. Bobos M, Hytiroglou P, Kostopoulos I, Karkavelas G, Papadimitriou CS. Immunohistochemical distinction between Merkel cell carcinoma and small cell carcinoma of the lung. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28(2):99-104. doi:10.1097/01. DAD.0000183701.67366.C7

10. Harms PW, Harms KL, Moore PS, et al. The biology and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: Current understanding and research priorities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(12):763-776. doi:10.1038/s41571-018-0103-2

11. Gauci ML, Aristei C, Becker JC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline—update 2022. Eur J Cancer. 2022;171:203-231. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2022.03.043

12. Zaggana E, Konstantinou MP, Krasagakis GH, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma— update on diagnosis, management, and future perspectives. Cancers (Basel). 2022;15(1):103. doi:10.3390/cancers15010103

13. Lemos BD, Storer BE, Iyer JG, et al. Pathologic nodal evaluation improves prognostic accuracy in Merkel cell carcinoma: analysis of 5823 cases as the basis of the first consensus staging system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(5):751-761. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.056