What Caused These Changes on the Shins?

Case Report

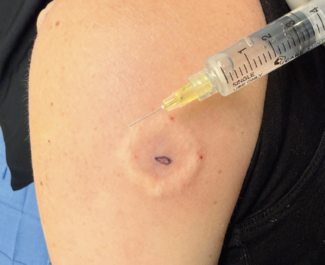

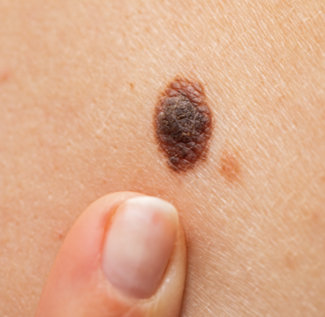

A 72-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes, obesity, and hypertension presented with multiple firm, well-circumscribed, reddish-brown, cystic lesions on both shins but more pronounced on his right shin (Figure). The lesions had been present for over 2 decades, initially appearing as small, flat areas that gradually became raised and discolored. Over the past year, one lesion began growing more rapidly, becoming firmer and more bulbous, particularly following minor trauma. The patient reported associated pruritus and occasional watery discharge but denied any pain.

What is your diagnosis?

Scroll below to find out!

Diagnosis: Pretibial Myxedema

Pretibial myxedema is an excess accumulation of glycosaminoglycan (GAG). This ground substance produced by fibroblasts is typically located within the reticular dermis and particularly over the shin area, acting as “cement” to anchor the fibrous and filamentous structures inside the dermis.1 Any factor that stimulates these fibroblasts increases GAG production.2

Pretibial myxedema is most commonly associated with Graves’ disease, an autoimmune-mediated thyroid condition in which thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin improperly binds and activates the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor, causing excess thyroid hormone production (thyroxine [T4] and triiodothyronine [T3]).3 Thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins affect more than just the thyroid gland, impacting the skin, muscles, and retro-orbital adipose tissue, leading to various manifestations of Graves’ disease.4

In the skin, GAG accumulation in the reticular dermis is a hallmark of the condition,5 with hyaluronic acid concentrations 6 to 16 times higher in affected lesions than in normal skin.6 Heat shock protein, IL-1, and TGF-β have also been implicated in pretibial myxedema, although their roles are not fully understood.7,8 Regardless of the trigger, excess GAG production results in the hallmark skin changes of pretibial myxedema. It may also compress or occlude small local lymphatics, leading to dermal edema.9

Pretibial myxedema typically requires both genetic predisposition and environmental triggers, such as trauma, smoking, obesity, or leg edema.10 In addition to Graves’ disease, other infrequent thyroid-related conditions can also precipitate the development of pretibial myxedema. These include Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, an autoimmune disorder characterized by chronic lymphocytic infiltration and hypothyroidism, as well as certain thyroid malignancies.11-13 In rare instances, primary hypothyroidism from other causes has also been associated with the manifestation of pretibial myxedema.14

An even rarer variant, known as obesity-related euthyroid pretibial mucinosis, has been reported in patients with chronic obesity and lymphedema.15 This condition is hypothesized to arise from the stagnation of lymphatic fluid and subsequent deposition of mucopolysaccharides within the dermal and subcutaneous tissues, independent of thyroid dysfunction. The accumulation of these mucins is thought to be a consequence of the lymphatic impairment characteristic of the obese state.16

While the term thyroid dermopathy has gained more recent usage, the traditional designation of pretibial myxedema remains a widely recognized descriptor for this condition.17,18 Although the lesions may extend beyond the typical pretibial regions to other sites, pretibial myxedema remains valid for capturing the most common and characteristic presentation.

Clinical Presentation

Although often asymptomatic, pretibial myxedema may cause pruritus, discomfort, or functional limitations in some patients.19 Additionally, the cutaneous findings may be subtle, and patients may be primarily focused on the more prominent symptoms of thyrotoxicosis or thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy, thus overlooking the skin manifestations.3

While the lower extremities, particularly the shins, represent the classic sites of involvement, the clinical presentation of pretibial myxedema can extend beyond this typical distribution.18 Lesions have been documented on the upper extremities, shoulders, digits, elbows, upper back, knees, toes, and even the pinnae, nose, and scalp.20 Lesions in atypical locations often follow local trauma, such as surgical scars,21 burns,22 or vaccination sites.23

Classically, pretibial myxedema presents as flesh-colored or yellowish, waxy lesions on the shins, with a firm, peau d’orange-like texture due to the prominence of follicular openings.3 These bilateral, symmetrical lesions typically involve the lower extremities, but can also present with overlying hyperpigmentation, scaliness,18 or visible sweating.24,25 Progressive forms include diffuse, plaque-like, and nodular variants; rare types include elephantine and mixed forms.18,19

Differential Diagnosis

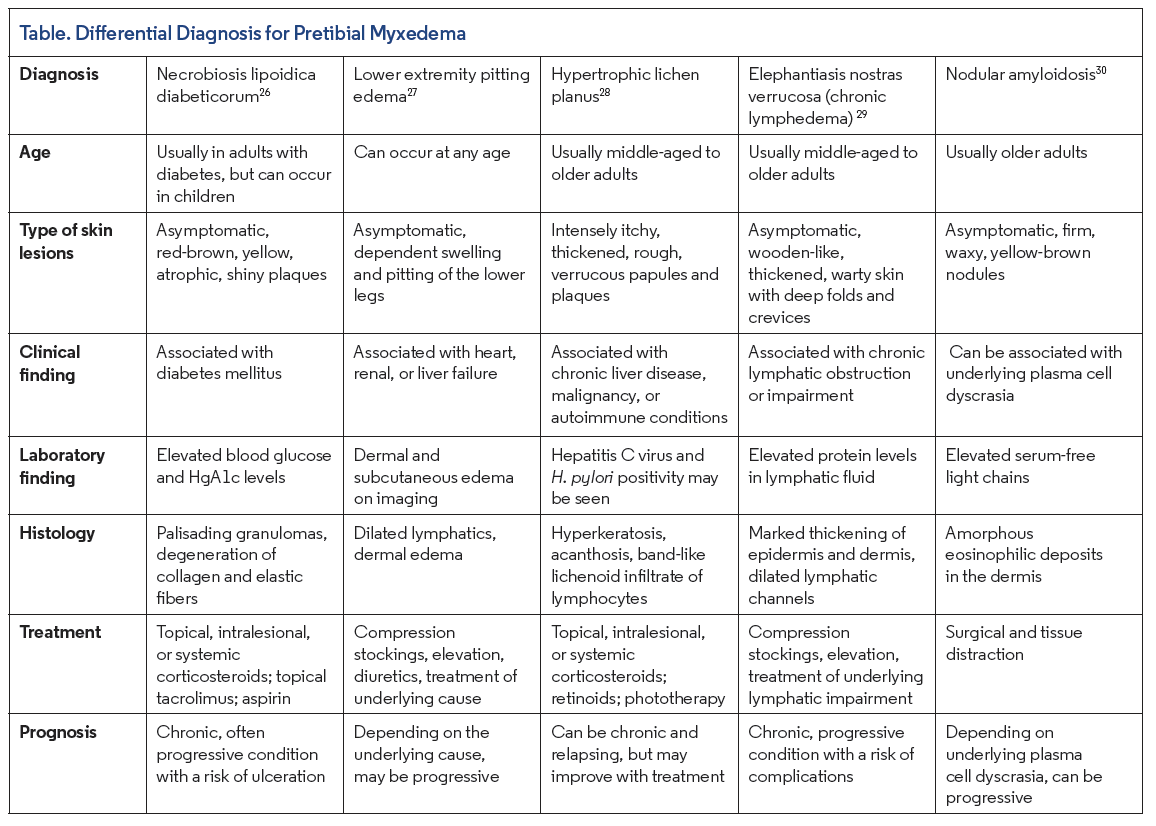

The differential diagnosis for pretibial myxedema is broad and depends on the lesion morphology and site. Some of the most important differential diagnoses to consider are necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum, lower extremity pitting edema, hypertrophic lichen planus, elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (chronic lymphedema), and nodular amyloidosis (Table).26-30

Histopathology

Microscopically, there is abundant mucin visible initially in the papillary dermis, with further progression into the reticular dermis. There is no significant increase in dermal fibroblasts. The epidermis shows variable hyperkeratosis, and a mild superficial perivascular mixed infiltrate is often seen.

Management

Key principles include risk factor control, thyroid regulation, pharmacologic therapy, compression, and surgery.31

The initial treatment focuses on minimizing risk factors, such as weight reduction, smoking cessation, and normalization of thyroid function.6 While the benefit of normalizing thyroid function in pretibial myedema is not fully proven, evidence from thyroid ophthalmopathy suggests that normalization may be beneficial, as both conditions share similar pathogenesis. However, care should be taken to avoid prolonged hypothyroidism.6

Our Patient

The patient underwent a comprehensive evaluation, including a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, fasting blood sugar (FBS), HbA1c, and thyroid function tests. Results revealed uncontrolled diabetes (FBS: 172 mg/dL, HbA1c: 8.3%) but normal TSH, free T4, and free T3 levels. A punch biopsy of the skin lesion showed abundant mucin deposition in both the papillary and reticular dermis, interspersed with thin collagen fibrils, and no significant inflammatory infiltrate, which is characteristic of pretibial myxedema.

Conclusion

Diagnosis of pretibial myxedema was made based on clinical and histologic findings, despite normal thyroid function. The patient was counseled on lifestyle and dietary modifications, weight loss, and improved glycemic control. Treatment included intra-lesional triamcinolone acetonide injections (diluted to 20 mg/mL) administered every 2 weeks, along with compression therapy using elastic bandages. The patient was followed biweekly for 2 months, during which he showed significant clinical improvement with reduced lesion size, firmness, and symptoms, and no new lesions appearing.

Dr Alem is an assistant professor of dermatovenereology in the department of dermatology at the University of Gondar in Gondar, Ethiopia. Dr Melaku is an assistant professor of dermatology and a dermatopathology fellow in the department of dermatology at Addis Ababa University in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Dr Khachemoune is a dermatologist at Premier Dermatology in Ashburn, VA, and the Derm DX section editor.

Disclosure: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Georgala S, Katoulis AC, Georgala C, et al. Pretibial myxedema as the initial manifestation of Graves’ disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16(4): 380-383. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00567.x

2. Jolliffe DS, Gaylarde PM, Brock AP, Sarkany I. Pretibial myxoedema: stimulation of mucopolysaccharide production of fibroblasts by serum. Br J Dermatol. 1979;101(5):557-560.

3. Schwartz KM, Fatourechi V, Ahmed DD, Pond GR. Dermopathy of Graves’ disease (pretibial myxedema): long-term outcome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(2):438-446. doi:10.1210/jcem.87.2.8220

4. Varma A, Rheeman C, Levitt J. Resolution of pretibial myxedema with teprotumumab in a patient with Graves’ disease. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6(12):1281-1282. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.09.003

5. Kriss JP. Pathogenesis and treatment of pretibial myxedema. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1987;16:409-415.

6. Cheung HS, Nicoloff JT, Kamiel MB, Spolter L, Nimni ME. Stimulation of fibroblast biosynthetic activity by serum of patients with pretibial myxedema. J Invest Dermatol. 1978;71(1):12-17. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12543646

7. Heufelder AE, Wenzel BE, Gorman CA, Bahn RS. Detection, cellular localization, and modulation of heat shock proteins in cultured fibroblasts from patients with extrathyroidal manifestations of Graves’ disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;73(4):739-745. doi:10.1210/jcem-73-4-739

8. Korducki JM, Loftus SJ, Bahn RS. Stimulation of glycosaminoglycan production in cultured human retroocular fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33(6):2037-2042.

9. Bull RH, Coburn PR, Mortimer PS. Pretibial myxoedema: a manifestation of lymphoedema? Lancet. 1993;341(8847):403-404. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(93)92990-b

10. Farid NR. Immunogenetics of autoimmune thyroid disorders. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1987;16(2):229-245.

11. Nair PA, Mishra A, Chaudhary A. Pretibial myxedema associated with euthyroid Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(6):YD01-YD02. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/6581.4415

12. Cannavò SP, Borgia F, Vaccaro M, Guarneri F, Magliolo E, Guarneri B. Pretibial myxoedema associated with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16(6):625-627. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00532.x

13. Fery-Blanco C, Pelletier F, Humbert P, Aubin F. [Medullar cancer of the thyroid associated with dermal mucinosis]. Rev Med Interne. 2006;27(12):954-957. doi:10.1016/j.revmed.2006.08.003

14. Dharmalingam M, Seema G, Khaitan B, Karak A, Ammini AC. Plaque form of pretibial myxedema in hypothyroidism. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2001;67(6):330-331.

15. Ambachew R, Yosef T, Gebremariam AM, et al. Pretibial myxedema in a euthyroid patient: a case report. Thyroid Res. 2021;14(1):4. doi:10.1186/s13044- 021-00096-z

16. Rongioletti F, Donati P, Amantea A, et al. Obesity-associated lymphoedematous mucinosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(10):1089-1094. doi:10.1111/j.1600- 0560.2008.01239.x

17. Peacey SR, Flemming L, Messenger A, Weetman AP. Is Graves’ dermopathy a generalized disorder? Thyroid. 1996;6(1):41-45. doi:10.1089/thy.1996.6.41

18. Noppakun N, Bancheun K, Chandraprasert S. Unusual locations of localized myxedema in Graves’ disease: report of three cases. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122(1):85-88.

19. Siegler M, Refetoff S. Pretibial myxedema—a reversible cause of foot drop due to entrapment of the peroneal nerve. N Engl J Med. 1976;294(24):1383-1384. doi:10.1056/NEJM197606172942507

20. Lan C, Wang Y, Zeng X, Zhao J, Zou X. Morphological diversity of pretibial myxedema and its mechanism of evolving process and outcome: a retrospective study of 216 cases. J Thyroid Res. 2016;2016:2652174. doi:10.1155/2016/2652174

21. Wright AL, Buxton PK, Menzies D. Pretibial myxedema localized to scar tissue. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29(1):54-55. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1990.tb03758.x

22. Tong DW, Ho KK. Pretibial myxoedema presenting as a scar infiltrate. Australas J Dermatol. 1998;39(4):255-257. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.1998.tb01485.x

23. Pujol RM, Monmany J, Bagué S, Alomar A. Graves’ disease presenting as localized myxoedematous infiltration in a smallpox vaccination scar. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25(2):132-134. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00595.x

24. Kato N, Ueno H, Matsubara M. A case report of EMO syndrome showing localized hyperhidrosis in pretibial myxedema. J Dermatol. 1991;18(10):598-604. doi:10.1111/j.13468138.1991.tb03139.x

25. Gitter DG, Sato K. Localized hyperhidrosis in pretibial myxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(2 pt 1):250-254. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70207-x

26. Lepe K, Riley CA, Hashmi MF, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

27. Sleigh BC, Manna B. Lymphedema. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

28. Wang JH, Hung SJ. Lichen planus associated with hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and liver cirrhosis in a nationwide cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(4):1085-1086. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.085

29. Fredman R, Tenenhaus M. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. Eplasty. 2012;12:ic14.

30. Kubo EM, Ghislandi, C Tomiyoshi C, Mulinari-Brenner FA, Mukai MM. Nodular amyloidosis: good response to surgical treatment. Surg Cosmet Dermatol. 2016;8(1):82-84. doi:10.5935/scd1984-8773.201681701

31. Ren Z, He M, Deng F, et al. Treatment of pretibial myxedema with intralesional immunomodulating therapy. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;13:1189- 1194. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S143711