Soft Tissue Reconstruction With Synthetic Electrospun Fiber Matrix Following Musculoskeletal Injury: A Retrospective Case Series

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Restoration of a stable and functional soft tissue envelope following traumatic injury to the musculoskeletal system is critical. Where primary closure is not feasible, other reconstructive options must be considered to achieve soft tissue coverage of critical structures. Skin substitutes have been utilized to stimulate granulation tissue and support incorporation of autografts. This present study aims to investigate the use of a fully synthetic electrospun fiber matrix (SEFM) (Restrata; Acera Surgical, Inc) in the management of post-traumatic soft tissue defects. The objective of the present retrospective case series was to assess healing outcomes, including time to healing and incidence of complications, following a single application of the SEFM to soft tissue trauma surrounding musculoskeletal injury.

Methods. Medical charts of patients with soft tissue injury secondary to musculoskeletal trauma and who were treated with the SEFM in the operating room following bony instrumentation or fasciotomy procedures were retrospectively reviewed following institutional review board approval. Included patients were treated with the SEFM in conjunction with negative pressure wound therapy as a means of preparing open wounds for definitive management via split-thickness skin grafting or secondary intention healing.

Results. Eleven patients met the inclusion criteria. Injury etiologies included 8 open fractures in both upper and lower extremities, 2 open foot-crush injuries, and 1 incidence of forearm compartment syndrome. Ten patients achieved complete healing with minimal complications.

Conclusions. Preliminary results indicate that the SEFM may be a viable adjunctive treatment for open post-traumatic wound beds to promote granulation tissue for definitive closure.

Introduction

Traumatic injuries to the musculoskeletal system can have a significant impact on a patient’s function and quality of life. In particular, fractures associated with extensive soft tissue damage are at high risk of infection, decreased rates of bony union, and overall poor outcomes. These injuries present a high risk of developing infection and experiencing delays in healing.1 Restoration of a stable and functional soft tissue envelope is paramount in this setting. Following urgent irrigation and debridement of nonviable, necrotic, or infected tissue, soft tissue coverage should be achieved as soon as possible.2 Coverage of these traumatic defects is essential in reducing the risk of subsequent infections, ideally by providing a physical barrier to microbes and supporting revascularization.2 In complex open fractures where primary closure may not be feasible, other reconstructive options must be considered to achieve soft tissue coverage of bone, tendons, and other critical structures. Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) is thought to improve granulation tissue formation within deep wound beds and mitigate the risk of bacterial infection.3 NPWT in open fractures has mixed evidence supporting its ability to reduce time until definitive soft tissue coverage and infection mitigation compared with standard surgical dressings alone.3-4

The reconstructive ladder provides surgeons with an organized approach to wound closure. Once primary closure has been ruled out as a feasible approach, advanced wound therapies and surgical procedures should be considered to rapidly cover the defect and mitigate risk of further complication.3 Classically, in areas that lack appropriate tissue for healing by secondary intent or skin grafting, more invasive surgical approaches are warranted, such as the use of local soft tissue rearrangements, adjacent muscle flaps, or free tissue transfer. Skin substitutes may be utilized in clinical scenarios where promotion of granulation tissue in preparation for split-thickness skin grafting (STSG) or healing by secondary intention is appropriate. While these procedures provide rapid coverage and vascular supply, failure rates remain around 10% in the lower extremity.5 Initial flap failure is usually addressed with a secondary flap procedure, which is associated with a higher risk of failure than the initial (17%).5 Roughly 12% of patients who fail an initial flap procedure ultimately require amputation.5 Because of patient comorbidities, location of the injury, and availability of a qualified plastic surgeon, optimal soft tissue coverage procedures may not be feasible.5

When consideration is given to healing by secondary intent or as a bridge to skin grafting, the ideal skin substitute provides a physical barrier, mitigates infection risk, and stimulates both vascular ingrowth and granular tissue formation. The synthetic electrospun fiber matrix (SEFM) (Restrata; Acera Surgical, Inc) evaluated in the present retrospective case series is 510(K) cleared by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of various soft tissue defects and has demonstrated success in the reconstruction of traumatic wounds, as reported in the literature to date.6-9 The SEFM is a fully synthetic material composed of resorbable polymeric electrospun fibers (polyglactin 9:10 and polydioxanone), which are engineered to resemble human extracellular matrix (ECM) and thus encourage cellular infiltration and differentiation.9 The matrix itself is fully resorbable, and on average resorbs hydrolytically over a period of 1 to 3 weeks.9

The electrospun nature of the matrix allows for a high degree of conformability while maintaining the tensile strength of human skin. This conformability permits the application of the SEFM to wounds with difficult topography while maximizing contact with the wound bed.10 In prior clinical evaluations of the SEFM in wounds with challenging topography due to either wound location or nature of the injury, the SEFM has demonstrated the ability to remain adherent to the wound bed and stimulate wound-healing responses.7-9, 11-13

The current retrospective case series was conducted to evaluate the use of the SEFM in conjunction with NPWT to support healing of soft tissue defects following musculoskeletal trauma and evaluate critical clinical outcomes in terms of healing time, infection rate, and complications.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis of patient medical records was conducted to identify patients who received at least 1 application of the SEFM in the operating room to augment soft tissue healing secondary to open fractures or other traumatic orthopedic injuries by a single orthopedic surgeon at a single orthopaedic surgery center. Institutional review board (IRB) exemption was issued by the local governing agency considering the retrospective nature of the study and lack of identifiable patient information collected.

Medical charts from between November 2021 and March 2023 were retrospectively reviewed following IRB approval. For inclusion in this retrospective case series, patients must have been at least 18 years old at the time of their injury, undergone orthopedic reconstructive surgery for a traumatic injury, received at least 1 SEFM application to soft tissue trauma in the operating room, and returned for at least 1 follow-up visit to allow for assessment of the healing progress. Orthopedic trauma was considered to be any injury sustained to the musculoskeletal system. The SEFM was then applied to the injury as appropriate per the nature of the wound. This included placement over muscle flaps, amputation sites, or remaining areas of open wound that could not be primarily closed. The SEFM was hydrated with either saline or blood/wound exudate at the time of application to improve the pliability of the matrix and ensure its adherence to the contours of the wound bed. The SEFM was then stapled to the periphery utilizing a skin stapler and dressed with NPWT. The first follow-up appointment typically occurred 10 to 14 days postoperative, at which time NPWT was removed and wound dressings continued every 3 days with a nonadherent dressing.

Once the defect was sufficiently filled with even, healthy granulation tissue, patients either returned to the operating room for application of a STSG or the wound was allowed to heal through secondary intention based on wound size and patient preference. Patients who returned for at least 1 postoperative follow-up visit but were then lost to follow-up were documented as lost to follow-up (LTF).

The primary outcome measure was incidence of wound complications including infection and reoperation. During the patient’s standard postsurgical follow-up visits, the treating physician conducted assessments of the wound bed to monitor for signs of infection. This assessment included an evaluation of the amount of serous discharge, the presence of erythema or purulent exudate, and an evaluation of any evidence of tissue separation. If any of these indicators of infection were present, the treating physician utilized clinical judgment to determine the severity of the infection. If systemic antibiotics were indicated, an infection was documented. Reoperation was documented in the patient medical records as it occurred during the treatment and healing period. If an unplanned reoperation occurred during this period, the reason for the operation and the procedure were documented in the medical chart and reported as a complication.

Secondary outcome measures included the time to complete wound closure and the rate of complete wound closure. The time to complete wound closure was documented as an average in days to complete closure. Complete wound closure was documented in the patient medical record. Wound closure was considered to be either re-epithelialization of the wound without the need for additional dressings through secondary intention healing or application of an STSG to the wound site.

This study was intended to serve as an initial preliminary report of this use of the SEFM and evaluate outcomes to date in a small sample of patients. Given the exploratory nature of the study and the lack of control group, means, SDs, and descriptive statistics were used to present the results. Descriptive data reporting in the form of averages, SDs, and percentages were used to report the outcomes.

Results

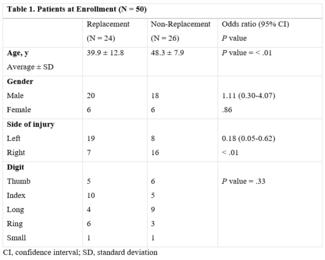

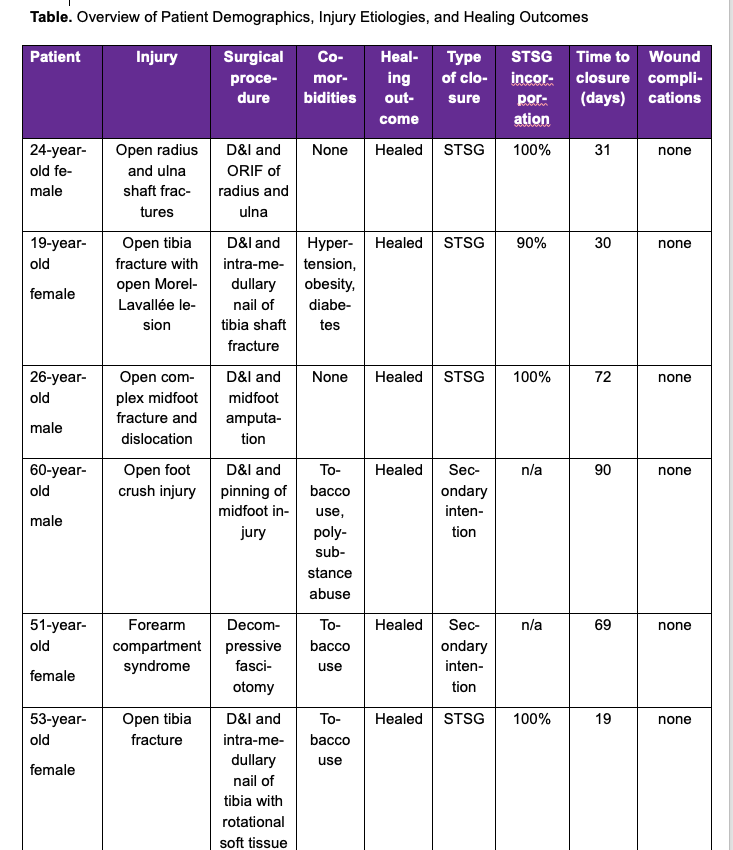

Eleven patients ranging in age from 19 to 60 years met the inclusion criteria. Injury etiologies included 8 patients with open fractures (tibia, radius, ulna, midfoot, and fibula), 2 open foot-crush injuries, and 1 incidence of forearm compartment syndrome. Injuries were managed with debridement and irrigation (D&I) and a combination of open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), intramedullary nailing, percutaneous pinning, partial amputation, decompressive fasciotomy, and rotational muscle flap as appropriate to address the soft tissue injury. Local antibiotic powder was utilized in all fracture cases; however, this was not necessarily adjacent to the SEFM. Individual patient demographics and healing outcomes can be found in the Table.

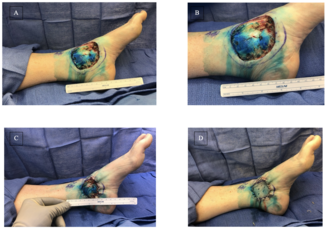

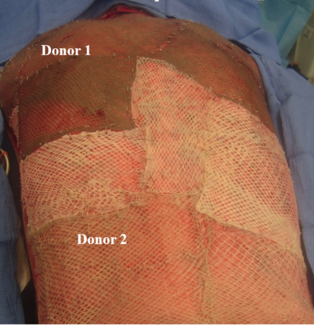

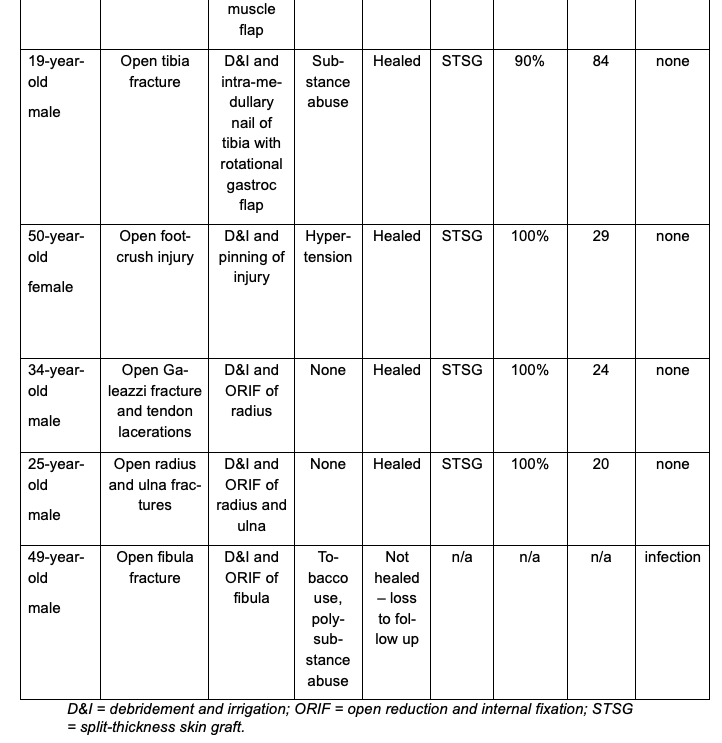

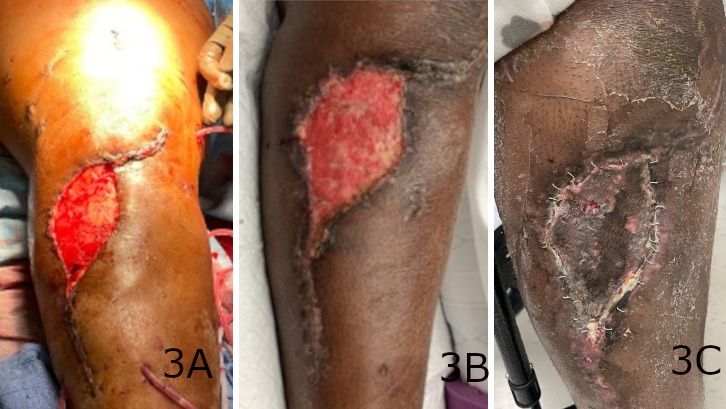

One of the 11 included patients returned with a documented infection after a prolonged malfunction of their NPWT device resulted in tissue maceration. This patient was treated with debridement and was then LTF prior to healing. The remaining 10 patients achieved successful soft tissue closure without complication. Eight of 10 patients went on to receive a STSG, and 2 healed through secondary intention. The average time to STSG following application of the SEFM was 39 days, with the time to STSG ranging from 19 to 84 days. The average time to complete soft tissue healing or definitive closure for all healed patients was 48 days, ranging from 19 to 99 days. STSG patients who continued additional follow-up had an average of 98% skin graft incorporation. Representative healing images can be found in Figures 1 through 3. No documented incidences of wound necrosis, hematoma formation, seroma formation, or unplanned reoperation were reported in the cohort with completed follow-up.

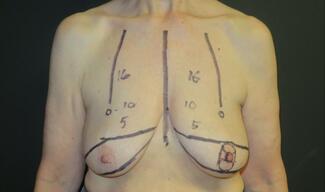

Figure 1. (A) Initial presentation of a traumatic forearm injury with compartment syndrome. Progressive healing of the post-fasciotomy wound at (B) 5 weeks post-intervention and initial SEFM application, and (C) the nearly closed post-fasciotomy wound at week 8.

Figure 2. (A) The soft tissue defect after amputation due to a mid-foot crush injury. (B) The synthetic electrospun fiber matrix application stapled into the wound bed and then (C) resorbed into the wound bed 3 weeks later. (D) The wound was healed following application of a split-thickness skin graft with complete uptake in the wound.

Figure 3. (A) A remaining soft tissue defect after intramedullary nail fixation of an open tibia shaft fracture, which (B) was fully granulated and prepared for skin grafting at week 4 and (C) demonstrated a 90% graft take 3 weeks later.

Discussion

In this retrospective case series, 91% of traumatized patients achieved successful wound closure without complication following significant soft tissue injury requiring surgical debridement. Traumatic injuries, as evidenced by this patient cohort, are often contaminated and at risk for infection, delayed healing, or desiccation.14 Our primary outcome measures of infection and reoperation were recorded in none of the patients who had completed follow-up, which is in stark contrast to the high baseline infection rate (15%-25%) that has been established in the literature for similar open fractures with soft tissue defects.27

Soft tissue reconstruction following musculoskeletal trauma aims to both prevent wound healing complications and restore vascularity to exposed underlying structures such as bone, tendon, or ligaments.14 When considering the advancement of orthopedic surgical techniques, improved antibiotic applications, and use of NPWT, there remains a persistently high infection rate in open fractures with soft tissue defects requiring soft tissue coverage.15 Between 2002 and 2011, the time to soft tissue reconstruction following lower extremity trauma doubled from 6.12 days to 12.5 days.15 This delay to wound coverage and lack of availability of qualified soft tissue surgeons is a common reality in many orthopedic practice environments. NPWT alone has been utilized to support healing responses for subsequent definitive closure, with time to coverage reported at an average of 40.8 days in 1 systematic review with an infection rate of 19.5%.4 This is similar to the time to soft tissue coverage reported in the current study utilizing both SEFM and NPWT (39 days), while the current study demonstrates a lower infection rate (9%). Both of these studies included a variety of wound etiologies; however, the systematic review of NPWT was exclusive to leg injuries and included a much larger set of patient data.4 Current research assessing the use of the SEFM in conjunction with NPWT in traumatic injuries needs be expanded beyond this initial case series to elucidate the exact effects on wound-healing responses.

Dermal skin substitutes have also been utilized in both upper and lower extremity trauma reconstructions published to date as a means of providing coverage or stimulating healing responses in preparation for subsequent STSG.16 This is practiced especially in instances where donor tissue availability is limited.16 Acellular dermal matrices utilized in post-traumatic soft tissue reconstruction have generally demonstrated positive outcomes in terms of successfully granulating healthy tissue at the wound site and subsequent successful STSG engraftment.17-19 Prior studies utilizing acellular dermal matrices in full-thickness lower extremity reconstruction have demonstrated improved STSG incorporation compared with STSG-only cases.18 An additional benefit of utilizing dermal matrices in this manner is the reduction in operative time compared with free flap procedures.20 One retrospective review reported an average procedure time of 408 minutes vs 50 minutes in lower extremity reconstruction performed with a free flap or an acellular dermal matrix, respectively.20 This reduction in operative time reduces cost in operating room time and limits the risk of infection associated with longer procedure times.

In this case series, the SEFM was placed over critical exposed structures such as bone, periosteum, tendon, muscle, and fascia to support granulation tissue formation. This technique was used in preparation for definitive closure via STSG or healing by secondary intention and may significantly expand the surgeon’s capacity to primarily manage these traumatic wounds without the need for advanced soft tissue reconstructive techniques. The SEFM may aid in supporting the organized wound-healing responses critical to success in this patient population through its structure and degradation rate.6,9

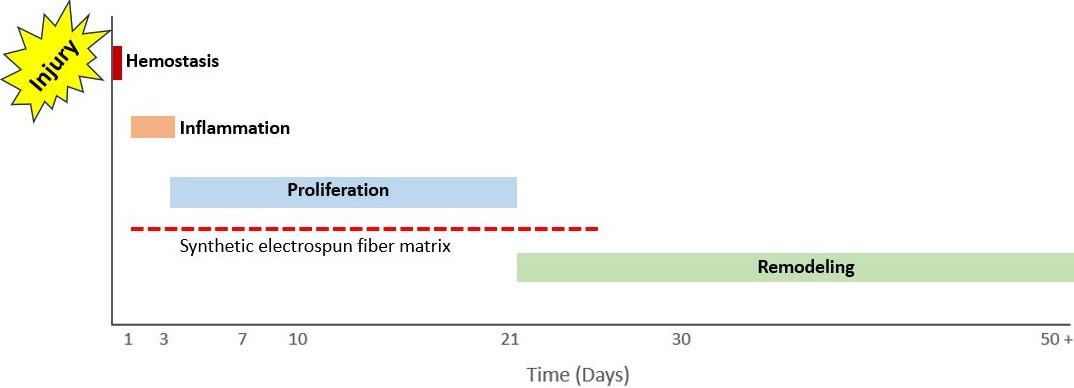

Wound healing occurs in 4 stages (hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling), all of which have some degree of overlap. Following hemostasis and blood-clot formation, the wound enters the inflammatory stage; this occurs within 1 day of the injury and on average lasts for roughly 4 days. During this time, neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages clear debris from the wound to prevent infection, in addition to releasing proinflammatory cytokines that are responsible for the recruitment of fibroblasts and epithelial cells.21 Following these inflammatory responses, the wound enters the proliferative phase, which occurs from day 4 until day 21. The recruited fibroblasts migrate, and angiogenesis begins to occur. Fibroblast migration is critical to supporting ECM formation and stimulating collagen formation.21 Angiogenesis is critical to maintain tissue viability in the healing wound and is supported by the local wound environment, including low pH values and high lactate levels.16 For the next several months to years following this phase, the wound enters the remodeling phase, in which scar tissue is replaced by a less disorganized ECM.21 The SEFM application is typically performed within the first few days of injury, persists within the wound for roughly 3 weeks following injury, and is essentially present throughout the inflammatory and proliferative phases of wound healing (Figure 4).22

Figure 4. A timeline of the wound healing phases and the synthetic electrospun fiber matrix’s presence within the wound bed.

Since the SEFM mimics native ECM, it provides a framework to support these processes in an organized way. Fibroblast attraction and activation from the surrounding soft tissue is essential to ensure timely healing responses.14 The polymers of the SEFM are aligned in a way that supports fibroblast migration into the wound site, subsequently supporting differentiation and organized collagen deposition, both of which are critical to encourage granulation tissue formation and closure of the wound with native dermal structure.14,22-23 Synthetic polymers have demonstrated the ability to influence the proliferation and migration of fibroblasts and mesenchymal cells.22 The varying pore and synthetic fiber sizes within the SEFM are engineered to be within the range to support both this process as well as retention of these cells during resorption through the increasing porosity of the matrix structure.6,9

The polymers themselves, polyglactin 9:10 and polydioxanone, have demonstrated that, upon degradation, they produce lactic acid as a byproduct, which could in theory support angiogenesis.21 In-vitro models evaluating the SEFM’s ability to stimulate vascularization within full-thickness wounds have demonstrated numerous blood vessels interspersed throughout the wound at day 15.22 This outcome was further documented in a clinical case report demonstrating moderate vascularization and collagen deposition in a periosteum-devoid calcaneal defect, despite prior failures of NPWT and a history of flap failures.24

These wounds also present a high risk of infection, which, if not addressed, can lead to further wound complications and operations.25 Open fractures in particular present with high rates of bacterial colonization and infection.25 The synthetic nature of the SEFM may also offer added benefit here, as the lack of biologic material does not provide a nutrient substrate for microbes present within the wound bed as comparative xenograft substitutes may. Benchtop testing of the SEFM conducted per the United States Pharmacopeia (USP)51 standards for Antimicrobial Effectiveness Test demonstrated passing results when tested against the most commonly documented microbes detected in nonhealing wounds.26 These promising in vitro results, while they have not been formally tested in a clinical setting, demonstrated effectiveness against the infectious organisms that are most likely to result in healing complications.5, 26

Limitations

While the results presented in the present retrospective case series are promising, this study is limited by the inherent biases of a retrospective review with small sample size. Other distinct limitations include the lack of control group and the heterogeneity of the open fracture types, injury etiologies, and locations.

Conclusions

This case series is the first to highlight the use of the SEFM in the realm of orthopedic trauma. In this patient cohort, none of the patients with completed follow-up had a reported primary outcome event of infection or reoperation, despite significant soft-tissue injury. Further research is warranted to understand the effect of the SEFM in this patient population.

Acknowledgments

Author: Christopher Cosgrove, MD

Affiliation: Campbell Clinic Orthopaedics, Memphis, Tennessee

Correspondence: Christopher Cosgrove, MD, Campbell Clinic Orthopaedics, 1211 Union Ave, Suite 500, Memphis, TN 38104, USA. Email: ccosgrove@campbellclinic.com

Ethics: Institutional review board (IRB) exemption was granted by the University of Tennessee Health Science Center IRB (# 23-09314-XM) due to retrospective study design and lack of identifiable patient information.

Funding: Dr Cosgrove received funds for time spent on data collection in the form of a consulting agreement with Acera Surgical, Inc.

Disclosures: Dr Cosgrove is a paid consultant for Acera Surgical, Inc.

References

-

Coles CP. Open fractures with soft-tissue loss: coverage options and timing of surgery. OTA Int. 2020;3(1):e053. doi:10.1097/OI9.0000000000000053

-

Marais LC, Hungerer S, Eckardt H, et al; FRI Consensus Group. Key aspects of soft tissue management in fracture-related infection: recommendations from an international expert group. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2024;144(1):259-268. doi:10.1007/s00402-023-05073-9

-

Park JJ, Campbell KA, Mercuri JJ, Tejwani NC. Updates in the management of orthopedic soft-tissue injuries associated with lower extremity trauma. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2012;41(2):E27-E35.

-

Barone N, Ziolkowski N, Haykal S. The role of negative pressure wound therapy in temporizing traumatic wounds before lower limb soft tissue reconstruction: a systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12(7):e6003. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000006003

-

Koster ITS, Borgdorff MP, Jamaludin FS, de Jong T, Botman M, Driessen C. Strategies following free flap failure in lower extremity trauma: a systematic review. JPRAS Open. 2023;36:94-104. doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2023.03.002

-

Chowdhry S. Utility of a synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix in surgical soft tissue reconstruction. Eplasty. 2024;24:e2.

-

Fernández L, Matthews M, Kim PJ, Barghuthi L, MacEwan M, Sallade E. Clinical application of a synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix in a pediatric trauma patient. Wounds. 2023;35(8):E248-E252. doi:10.25270/wnds/23039

-

Martini CJ, Burgess B, Ghodasra JH. Treatment of traumatic crush injury using a synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix in conjunction with split-thickness skin graft. Foot & Ankle Surgery: Techniques, Reports & Cases. 2022;2(1):100112. doi:10.1016/j.fastrc.2021.100112

-

MacEwan M, Jeng L, Kovács T, Sallade E. Clinical application of bioresorbable, synthetic, electrospun matrix in wound healing. Bioengineering (Basel). 2022;10(1):9. doi:10.3390/bioengineering10010009

-

MacEwan MR, MacEwan S, Kovacs TR, Batts J. What makes the optimal wound healing material? A review of current science and introduction of a synthetic nanofabricated wound care scaffold. Cureus. 2017;9(10):e1736. doi:10.7759/cureus.1736

-

Fernandez L, Shar A, Matthews M, et al. Synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix in the trauma and acute care surgical practice. Wounds. 2021;33(9):237-244. doi:10.25270/wnds/2021.237244

-

Herron K. Treatment of a complex pressure ulcer using a synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix. Cureus. 2021;13(4):e14515. doi:10.7759/cureus.14515

-

Fernandez LG, Orsi C, Okeoke B, et al. Synergistic clinical application of synthetic electrospun fiber wound matrix in the management of a complex traumatic wound: degloving left groin and thigh auger injury. Wounds. 2024;36(4):124-128. doi:10.25270/wnds/23117

-

Chan JKK, Harry L, Williams G, Nanchahal J. Soft tissue reconstruction of open fractures of the lower limb: muscle versus fasciocutaneous flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(2):284e-295e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182589e63

-

Zeiderman MR, Pu LLQ. Contemporary approach to soft-tissue reconstruction of the lower extremity after trauma. Burns Trauma. 2021;9:tkab024. doi:10.1093/burnst/tkab024

-

Fuenmayor P, Huaman G, Maita K, et al. Skin substitutes: filling the gap in the reconstructive algorithm. Trauma Care. 2024;4(2):148-166. doi:10.3390/traumacare4020012

-

Graham GP, Helmer SD, Haan JM, Khandelwal A. The use of Integra dermal regeneration template in the reconstruction of traumatic degloving injuries. J Burn Care Res. 2013;34(2):261-266. doi:10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182853eaf

-

Kim YH, Hwang KT, Kim KH, Sung IH, Kim SW. Application of acellular human dermis and skin grafts for lower extremity reconstruction. J Wound Care. 2019;28(Suppl 4):S12-S17. doi:10.12968/jowc.2019.28.sup4.s12

-

Pontell ME, Saad N, Winters BS, Daniel JN, Saad A. Reverse sural adipofascial flaps with acellular dermal matrix and negative-pressure wound therapy. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2018;31(1):612-617. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000527290.81581.af

-

Kozak GM, Hsu JY, Broach RB, et al. Comparative effectiveness analysis of complex lower extremity reconstruction: outcomes and costs for biologically based, local tissue rearrangement, and free flap reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(3):608e-616e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000006589

-

Schultz GS, Chin GA, Moldawer L, Diegelmann RF. Principles of wound healing. In: Fitridge A, Thompson M, eds. Mechanisms of Vascular Disease: A Reference Book for Vascular Specialists. [Internet]. University of Adelaide Press; 2011. Accessed September 26, 2025. https://www.adelaide.edu.au/press/titles/vascular

-

MacEwan MR, MacEwan S, Wright AP, Kovacs TR, Batts J, Zhang L. Comparison of a fully synthetic electrospun matrix to a bi-layered xenograft in healing full thickness cutaneous wounds in a porcine model. Cureus. 2017;9(8):e1614. doi:10.7759/cureus.1614

-

Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. Fibroblasts and their transformations: the connective-tissue cell family. In: Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P, eds. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th ed. Garland Science; 2002. Accessed September 26, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26889/

-

Harder JG, Hernandez EJ, MacEwan MM, et al. Histopathologic analysis of a recalcitrant calcaneal wound treated using a synthetic hybrid-scale fiber matrix. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12(2):e5597. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000005597

-

Coombs J, Billow D, Cereijo C, Patterson B, Pinney S. Current concept review: risk factors for infection following open fractures. Orthop Res Rev. 2022;14:383-391. doi:10.2147/ORR.S384845

-

Sallade E, Grimes D, Jeng L, MacEwan MR. Antimicrobial effectiveness testing of resorbable electrospun fiber matrix per United States Pharmacopeia (USP) <51>. Cureus. 2023;15(12):e50055. doi:10.7759/cureus.50055