Wolverine Hand: Intramedullary Threaded Nail Fixation of Four Metacarpal Fractures

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Questions

- What is the incidence of metacarpal fractures? How are they evaluated? How are they managed nonoperatively?

- What are the indications for open reduction and internal fixation of metacarpal fractures? Which fractures are suited to intramedullary screw fixation?

- What are the clinical outcomes of intramedullary fixation?

- What are the advantages of threaded intramedullary nail vs intramedullary screw fixation? What are some key technical pearls of the use of threaded intramedullary nails?

Case Description

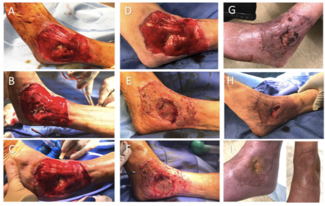

A 36-year-old right-hand dominant man presented with right-hand pain and deformity after falling from a motorized bicycle at moderate speed. Radiography revealed a nondisplaced oblique fracture of the second metacarpal base, a displaced transverse fracture of the third metacarpal base, a midshaft transverse fracture of the fourth metacarpal, and a neck fracture of the fifth metacarpal (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Preoperative radiographs of anteroposterior, oblique, and lateral views. Note the nondisplaced oblique fracture of the second metacarpal base, a displaced transverse fracture of the third metacarpal base, a midshaft transverse fracture of the fourth metacarpal, and a neck fracture of the fifth metacarpal.

A retrograde technique was utilized for the fifth metacarpal neck and the second and third metacarpal base fractures (Video 1). An anterograde technique was used for the fourth metacarpal shaft fracture (Video 2). Following fixation, final radiographs were taken, and fluoroscopy confirmed stability with movement (Figure 2; Video 3). The hand was placed in an intrinsic plus position and a short-arm volar splint was applied. The fixation of 4 metacarpals was completed in approximately 80 minutes of tourniquet time with the splint on.

Figure 2: Postoperative radiographs of anteroposterior, oblique, and lateral views. Note the anatomic reduction with intramedullary threaded nail fixation of the second, third, fourth, and fifth metacarpals.

The splint was discontinued on postoperative day 3 and the patient started hand therapy. At the 2-week follow-up, he had achieved near-full range of motion and was back to work without any major restriction.

Video 1: Demonstration of the retrograde 0.045-inch (1.1-mm) Kirshner guidewire placement technique.

Video 2: Demonstration of the anterograde-retrograde 0.045-inch (1.1-mm) Kirshner guidewire placement technique.

Video 3: Immediate post-fixation fluoroscopy demonstrating stable reduction with full range of motion.

Q1. What is the incidence of metacarpal fractures? How are they evaluated? How are they managed nonoperatively?

Metacarpal fractures are the second most common orthopedic fracture, making up 11.2% of all fractures and 33% of all hand fractures.1,2 Metacarpal fractures occur at a rate of 13.6 per 100 000 person-years in the United States and are the most common in young and active patients in the first and second decades of life.1,2 They are 4.45 times more common in males than in females and most commonly occur after a direct blow or fall.2

Evaluation of a suspected metacarpal fracture begins with an assessment for any open wounds suggestive of open fracture. Deformities present may include shortening, angulation, and malrotation. Physical exam may reveal crepitus, point tenderness, and instability. Radiography should be performed in all cases of suspected fracture with posteroanterior, lateral, and oblique views. Specialized views include the Brewerton view, which visualizes the finger metacarpal joints, and the Roberts view, which visualizes the thumb metacarpal.2

Stable metacarpal fractures may be treated nonoperatively. Reduction is achieved with the Jahss maneuver, wherein the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints are flexed with a volar proximal force at the metacarpal, and a distal dorsal force at the proximal phalanx is applied to distract the fracture and reduce the metacarpal head. A volar splint is then applied with the hand in an intrinsic plus position with the MCP joint flexed and the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint extended to prevent flexion contracture. Immobilization is maintained for a minimum of 4 weeks.3

Q2. What are the indications for open reduction and internal fixation of metacarpal fractures? Which fractures are suited to intramedullary screw fixation?

Unstable, displaced, shortened, angulated, and misaligned fractures, multiple fractures, and open fractures should undergo operative treatment.3,4 Every 2 mm of metacarpal shortening can lead to 7 degrees of extensor lag and alters the interosseus muscle biomechanics, leading to reduced grip strength.5 While up to 40 degrees of angulation may be tolerated in the small finger, progressively less angulation is tolerated as one proceeds radially; an angulation of greater than 10 degrees in the index finger warrants operative management. In this case, indications for surgery included the presence of multiple open fractures and the degree of angulation/displacement of the third metacarpal. Additional consideration was given to the serial digits involved, injury to the dominant hand, the patient’s occupation as a laborer, and his fitness for surgery.

Intramedullary fixation is a popular technique for metacarpal fractures first described by Grunberg in the 1970s.6 Orbay refined the technique with locking and non-locking nails in the 2000s, and Boulton introduced headless compression screws in 2010.7,8

Transverse or oblique metacarpal shaft fractures are particularly suited to intramedullary screw fixation. Intramedullary fixation should not be performed in cases of infection or in pediatric fractures with an open growth plate. Challenging fracture patterns to treat are long oblique or comminuted fractures. Compressive forces during screw fixation can lead to fracture collapse, displacement, and shortening of the metacarpal shaft. Specific techniques can prevent collapse, including the creation of a Y-strut in comminuted subcapital fractures with axial and oblique screws to provide an additional vector of stability, and the use of an axial strut with a shorter buried compression screw in comminuted metacarpal base fractures to purchase the proximal fragment before locking the distal end to limit excess deformational compressive forces.9 These techniques, however, greatly increase the technical complexity of fixation and do not address other fracture patterns.

Q3. What are the clinical outcomes of intramedullary fixation?

Intramedullary fixation of metacarpal fractures is generally well tolerated. A 2019 literature review by Beck et al of 9 articles and 169 metacarpal fractures found a radiographic union rate of 100%, with an average grip strength of 96% of the contralateral hand and an average digit total active motion of 251 degrees. Only 9 minor complications were reported: 4 cases of hardware removal, 2 at patient request and 2 for screw migration; and 5 cases of extensor lag, which may have been due to the initial trauma or an inadvertent extensor tendon injury during screw placement.10 A 2019 case series by Siddiqui et al of 32 patients with metacarpal fractures treated with intramedullary screw fixation found similar results with a high patient satisfaction rate, an early return to work at an average of 25 days, a mean postoperative grip strength of 38 kg, and a range of motion of 242 degrees, with only 3 cases of stiffness.11 A 2015 series by Pinal et al of 59 patients with 69 metacarpal and phalangeal fractures treated with intramedullary screw fixation found a 100% fracture healing rate, with a mean total active motion of 249 degrees at the MCP joint and full return to work or sports at 76 days, with only 2 patients requiring tenolysis.9

Advantages of intramedullary screw fixation include the limited dissection required for placement, leading to less complications such as adhesions and reducing the need for future hardware removal and tenolysis. Further advantages include the speed of placement, lower cost compared with plating, and greater stability than Kirschner wire fixation. Intramedullary compression screw fixation of hand fractures has become an increasingly popular technique to achieve rigid fixation rapidly and minimally invasively, supporting early range of motion and allowing for accelerated rehabilitation and earlier return to full activity.12

Q4. What are the advantages of threaded intramedullary nail vs intramedullary screw fixation? What are some key technical pearls of the use of threaded intramedullary nails?

The most recent evolution of intramedullary fixation is the INnate intramedullary threaded non-compressive nail system (ExsoMed), which received FDA premarket approval in 2019. Compared with an intramedullary screw, the threads on the threaded intramedullary nail are spaced further apart, reducing the deformational compressive force applied across the fracture while retaining the stabilizing rigidity and anti-rotational benefits of threads. This combination simplifies the deployment of rigid intramedullary fixation to oblique and comminuted fracture patterns with less concern for fracture collapse and metacarpal shortening. In a 2021 case series of 47 MCP fractures in 24 patients treated with INnate threaded intramedullary nail fixation, Cox et al found a time to radiographic healing of 9.7 weeks with a return to normal activity at 8.6 weeks in 85% of patients, and a greater than 75% total active motion in 87% of patients. They concluded that threaded intramedullary nail fixation offers the benefits of intramedullary screw fixation without the concern for metacarpal shortening and advocate its use in oblique or comminuted fractures at high risk of shortening.13

A key technical strategy utilized by the senior author to avoid shortening with INnate intramedullary nails is the maintenance of perfect reduction at the time of reaming. An additional point of consideration is proper screw diameter sizing by measuring the metacarpal isthmus, the narrowest points of the metacarpal, to avoid canal-screw size mismatch and prevent metacarpal shaft blowout.10 So long as the initial Kirschner guidewire has been properly placed, the cannulated system allows for easy reaming and screw placement. Care is taken with the final tightening of the threaded nail to avoid malrotation.

Acknowledgments

Authors: Dieter Brummund, MD1; Angela Chang, MD2; Tarik Husain, MD3

Affiliations: 1Larkin Community Hospital, Miami, Florida; 2HCA Florida – Mercy Hospital, Miami, Florida; 3Advanced Aesthetic Wellness, Miami Beach, Florida

Correspondence: Dieter Brummund, MD, Larkin Community Hospital, Miami, FL 33143, USA. Email: dbrummund@larkinhospital.com

Ethics: This review of 1 case and publicly available published literature was exempt from institutional review board approval.

Disclosures: Dr Husain is a speaker for Apyx Medical, the manufacturer of Renuvion—a helium plasma radiofrequency device for subdermal coagulation. The remaining authors disclose no financial or other conflicts of interest

References

- Court-Brown CM, Clement ND. The epidemiology of musculoskeletal injury. In: Tornetta P III, Ricci WM, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM, McKee MD, eds. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults. 9th ed. Vol 1. Wolters Kluwer; 2019:104-122

-

Nakashian MN, Pointer L, Owens BD, Wolf JM. Incidence of metacarpal fractures in the US population. Hand (N Y). 2012;7(4):426-430. doi:10.1007/s11552-012-9442-0

-

Wahl EP, Richard MJ. Management of metacarpal and phalangeal fractures in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2020;39(2):401-422. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2019.12.002

-

Marjoua Y, Eberlin KR, Mudgal CS. Multiple displaced metacarpal fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(9):1869-1870. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.04.032

-

Strauch RJ, Rosenwasser MP, Lunt JG. Metacarpal shaft fractures: the effect of shortening on the extensor tendon mechanism. J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23(3):519-523. doi:10.1016/S0363-5023(05)80471-X

-

Grundberg AB. Intramedullary fixation for fractures of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1981;6(6):568-573. doi:10.1016/S0363-5023(81)80134-7

-

Orbay JL, Touhami A. The treatment of unstable metacarpal and phalangeal shaft fractures with flexible nonlocking and locking intramedullary nails. Hand Clin. 2006;22(3):279-286. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2006.02.017

-

Boulton CL, Salzler M, Mudgal CS. Intramedullary cannulated headless screw fixation of a comminuted subcapital metacarpal fracture: case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(8):1260-1263. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.04.032

-

del Piñal F, Moraleda E, Rúas JS, de Piero GH, Cerezal L. Minimally invasive fixation of fractures of the phalanges and metacarpals with intramedullary cannulated headless compression screws. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(4):692-700. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.11.023

-

Beck CM, Horesh E, Taub PJ. Intramedullary screw fixation of metacarpal fractures results in excellent functional outcomes: a literature review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(4):1111-1118. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000005478

-

Siddiqui AA, Kumar J, Jamil M, Adeel M, Kaimkhani GM. Fixation of metacarpal fractures using intramedullary headless compression screws: a tertiary care institution experience. Cureus. 2019;11(4):e4466. doi:10.7759/cureus.4466

-

Chao J, Patel A, Shah A. Intramedullary screw fixation comprehensive technique guide for metacarpal and phalanx fractures: pearls and pitfalls. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9(10):e3895. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000003895

-

Cox C, Giron A, McKee D, MacKay BJ. Evaluation of post-operative outcomes in patients treated for metacarpal fractures utilizing the ExsoMed INnate threaded intramedullary nail. Abstract presented at: American Association for Hand Surgery (AAHS) Annual Meeting; January 2021. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://meeting.handsurgery.org/abstracts/2021/OD-Trauma28.cgi