Alligator Assault: A Systematic Literature Review and Case Series at a Florida Level 1 Trauma Center

© 2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Alligator bites are a rare occurrence, though some literature on injurious human-alligator interactions exists. This report details 3 cases of alligator bite-related wounds with characteristic extensive tissue damage and subsequent reconstruction. We also review the literature on caring for this specific population.

Methods. The authors present a systematic literature review on alligator bite-related sequalae and care. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines were followed throughout the systematic literature review. The authors also present a case series of patients wounded by alligators who each presented to a large tertiary academic center on the west coast of Florida.

Results. Early debridement, prophylactic antibiotics, soft tissue reconstruction, and interdisciplinary care are the main tenets of care for patients who sustain alligator bites. Case 1 was a 53-year-old man with a left upper extremity bite with significant neurovascular damage and near transradial amputation who underwent emergent revascularization. After multiple attempts at limb salvage, the patient underwent formal transradial amputation. Case 2 was a 77-year-old woman with bites to her left upper and lower extremities, with concern for lower extremity Morel-Lavallée lesion. The lower extremity wound was reconstructed with lateral gastrocnemius muscular and fibularis longus musculocutaneous flaps and split-thickness grafting; ultimately, transradial amputation was necessary for the upper extremity after evidence of devascularization. Case 3 was a 34-year-old man with a facial injury and skull fracture. After initial operative repair of the facial nerve and soft tissue lacerations, the patient required later revision with cranioplasty and temporalis coverage because of a draining wound. All 3 patients survived their severe injuries.

Conclusions. This case series represents a unique set of patients maimed by alligators and their subsequent surgical management. Recommendations from the literature review include an interdisciplinary approach, early operative investigation and initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics, and to consider a staged reconstruction for these injuries.

Introduction

Animal bites represent approximately 1% of emergency department visits in the United States, with the majority of these attributed to dogs.1 Alligator bites are far rarer, with an average of 7 reported cases per year.1 In the United States, there were 24 recorded deaths secondary to alligator bites from 1927 to 2009, and 15 of these occurred in Florida.2 An alligator encounter, if not lethal, can be severely traumatic, often causing significant limb deformation and infection. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission catalogued 372 alligator bite wounds over 56 years in the state with an increasing parallel to the alligator population growth, focusing on factors related to the bite rather than medical management.2,3 In this article, we outline what is known about these injuries, including the mechanics of the bite and the resultant soft tissue damage, as well as important aspects of caring for these wounds. We also present a 3-patient case series at a large academic tertiary care center in coastal Florida where these typically infrequent alligator traumas are more likely to present. Early considerations are hemorrhage control then infection prevention followed by surgical management, including soft tissue reconstruction.

Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for systematic reviews. Three databases (PubMed [National Institutes of Health], Embase [Elsevier], and Web of Science [Clarivate]) were searched using the search terms alligator bite and crocodile bite. Studies were included if they discussed alligator or crocodile bites to humans, reported novel patient data, were written in English, and the full text of the article was available. Studies were excluded if they did not discuss alligator or crocodile bites to humans, did not include novel patient data, were written in languages other than English, or if the full text was not available. The reference lists of the included articles were also reviewed to capture any additional relevant articles. Articles were initially screened by title, then abstract, and then full text. Titles were screened by 2 reviewers (B.K., S.M.) and abstracts and full texts were screened by 3 reviewers (B.K., S.M., J.S.).

Results

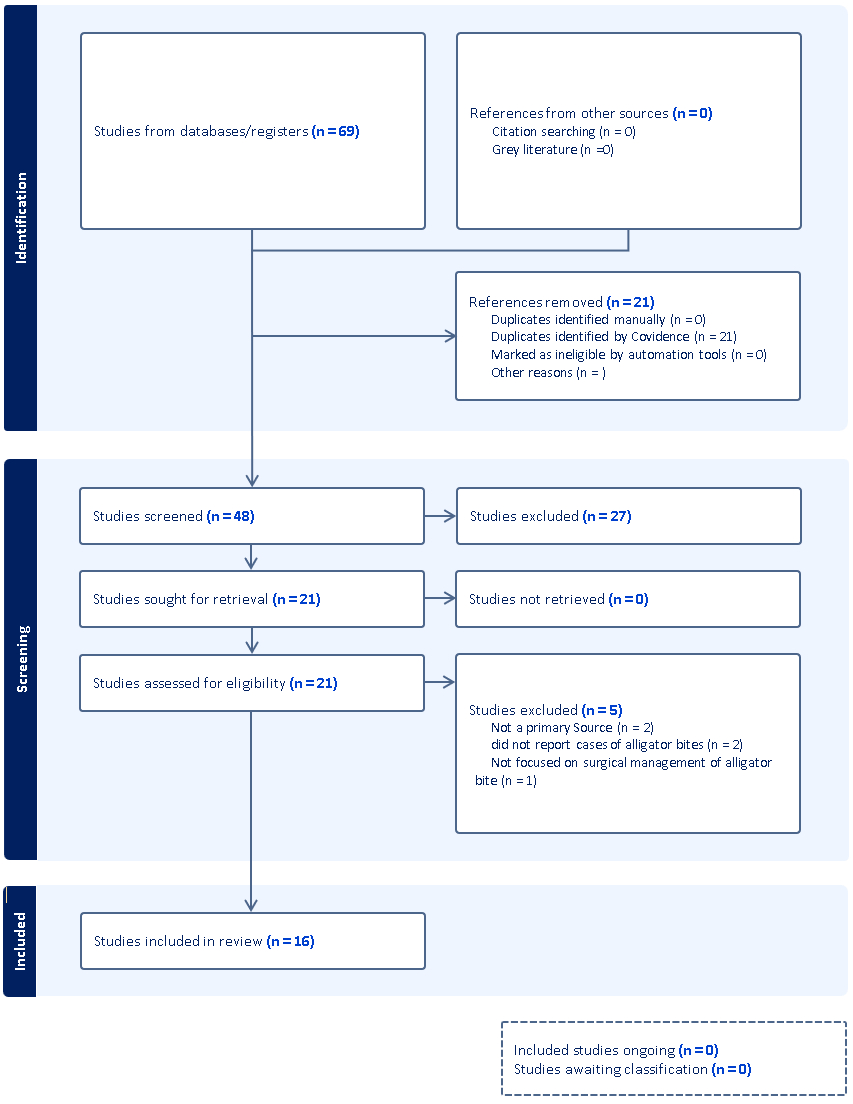

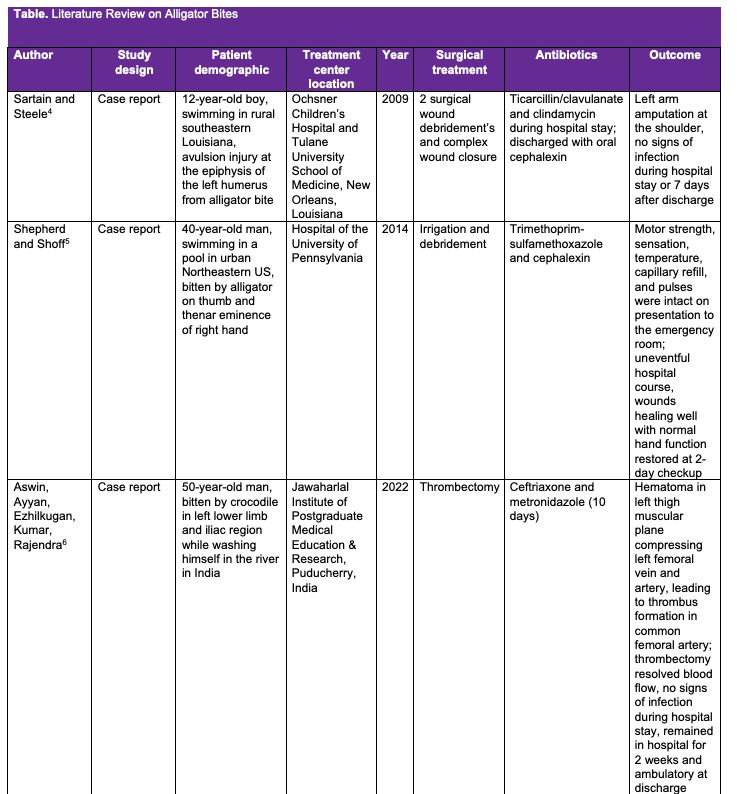

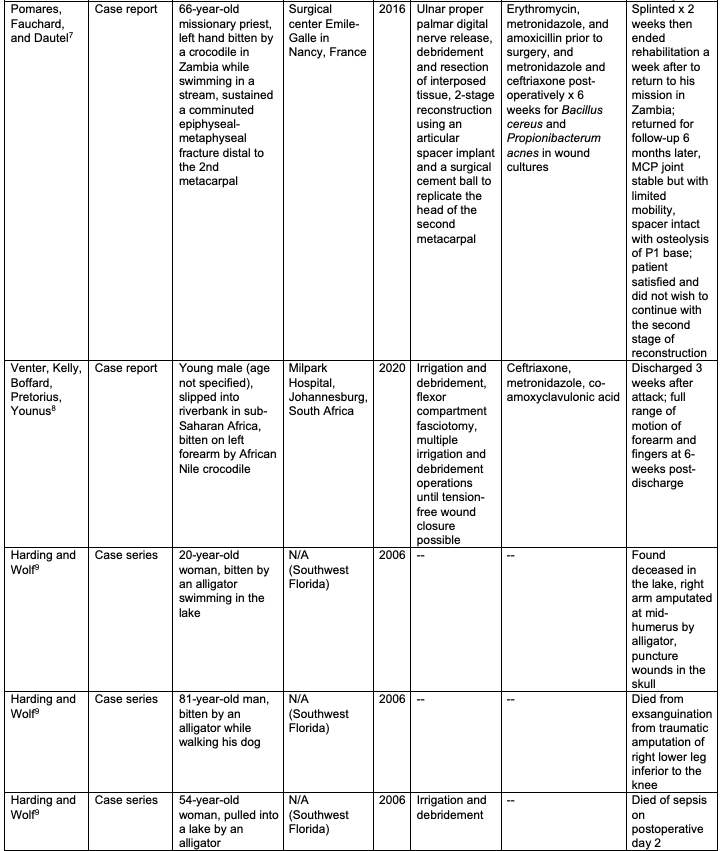

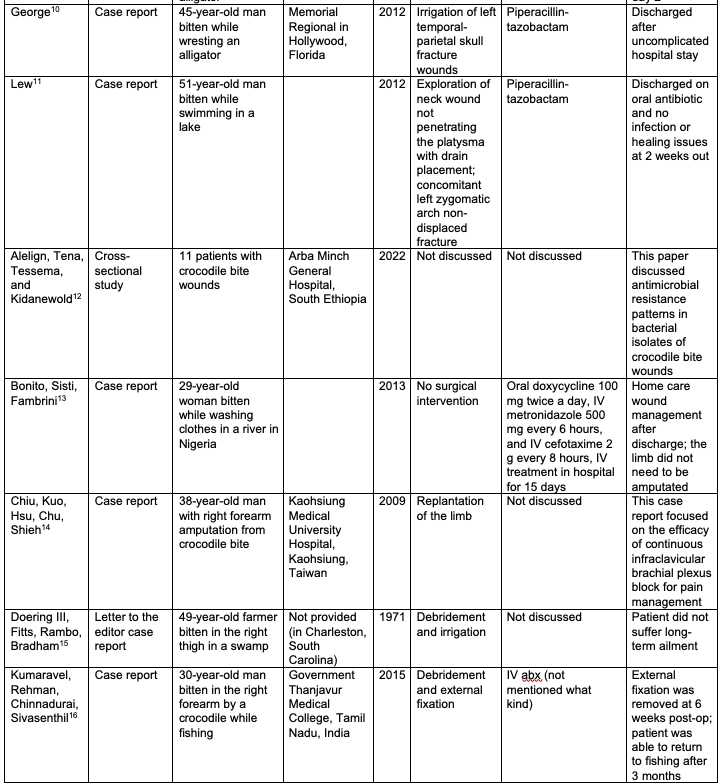

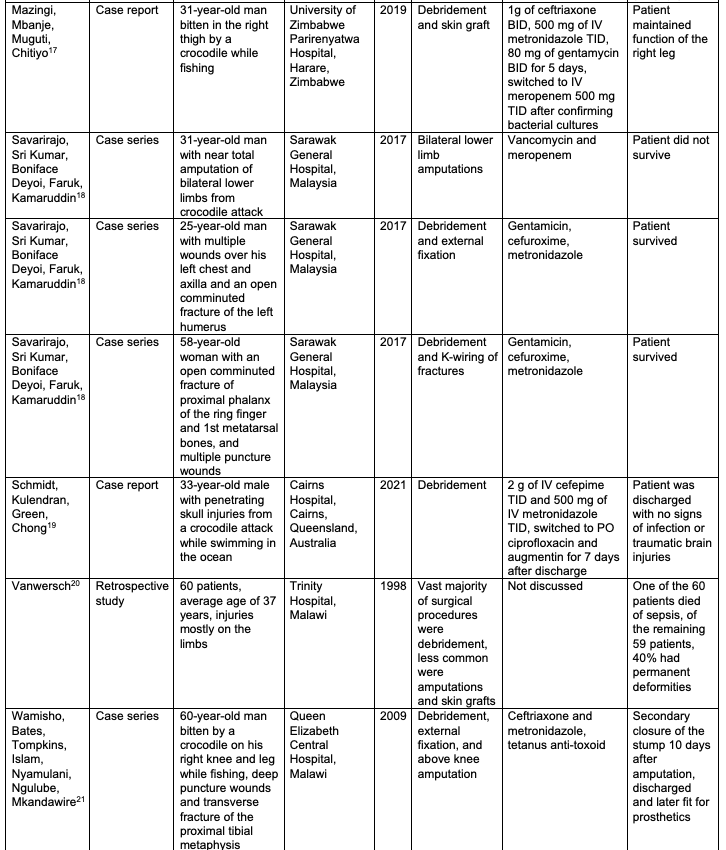

The database search resulted in 18 articles. Most studies were case reports (Level of Evidence 5). The results of the search are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses systematic review summary.

Systematic review

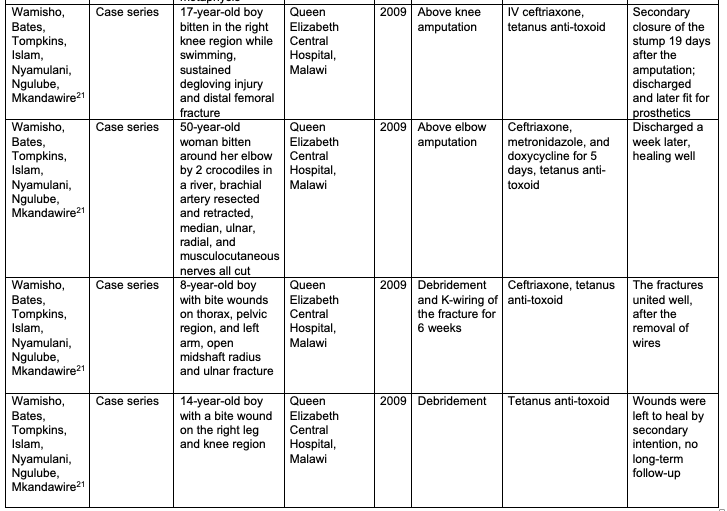

The findings of our systematic review are summarized in the Table.4-21 In summary, most of the literature on alligator bites comes from case reports, given the rarity of the event. More importantly, the literature review highlights that the majority of patients who suffer an alligator bite do survive. Generally, the bites were treated with irrigation debridement, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and delayed wound closure. We did not find any clear trends in antibiotic, surgical, or medical management for such injuries.

Case presentations

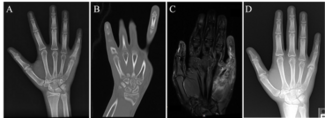

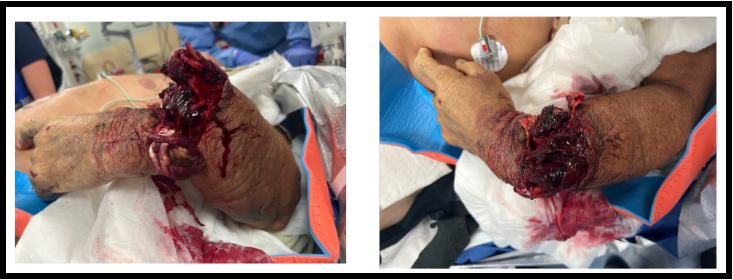

Case 1. A 53-year-old man with no significant past medical history presented to our emergency department with an alligator bite to the left forearm. He reported that, after the bite, the alligator performed a death roll, which is a maneuver performed by the animal when, after latching onto a prey, the alligator rotates its body on its long axis. Upon physical examination, there was a near-complete transradial amputation. The patient had complete loss of pulses, sensation, and function of the left hand. Grossly, there was a circumferential laceration to the mid-forearm through the muscle and tendon (Figure 2). Several tendons and major nerves were noted to be intact, though severely stretched and twisted. X-rays of the left forearm demonstrated open comminuted radial and ulnar shaft fractures (Figure 3). Prophylactically, the patient was administered a tetanus shot in the emergency department (ED) and started on vancomycin and cefepime. He was then taken to the operating room (OR) emergently for irrigation, debridement, and revascularization of the left arm.

Figure 2. Initial emergency department presentation of case 1; note torsion of soft tissues.

Figure 3. Initial X-ray of the left arm of case 1.

Because the patient’s nerves were still intact with sensation present, there was an attempt made to salvage the left hand. The arm was noted to be twisted along its axis and had to be untwisted several revolutions in a counterclockwise manner to properly align the distal extremity. The patient then underwent a left forearm open reduction and internal fixation of the radial and ulnar shaft fractures (Figure 4). The left ulnar artery was then repaired with an ipsilateral radial artery autograft. Two left forearm veins were repaired, one with a vein autograft. Additionally, forearm and hand fasciotomies and carpal tunnel release were performed, with initiation of negative pressure wound therapy. The primary goal was to stabilize the hand and ensure vascularity of the limb. As there was no obvious purulence, no cultures were obtained.

Figure 4. Intraoperative X-ray of the left arm after internal fixation of case 1.

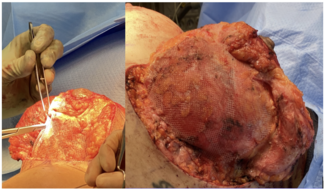

The patient was started on vancomycin and doxycycline per the recommendations of the infectious disease service. On the morning of hospital day 2, the patient developed blistering and darkening of digits (Figure 5). Cefepime was added to broaden bacterial coverage because of concern for a potential Vibrio infection. The patient was serially taken back for exploration and debridement on 3 occasions during the first week (Figure 6). One vein was noted to be thrombosed on the first repeat incision and drainage. The remaining vein and arterial anastomosis were subsequently found to be thrombosed and, approximately 1-week post-injury, it was determined that the upper extremity could not be salvaged. The patient was taken for left forearm transradial amputation with targeted muscle reinnervation, which included nerve transfers of the median ulnar and radial nerves to the reinnervation targets. Four days later, the patient underwent full-thickness skin grafting to the left volar surface of the forearm to cover a small portion of the exposed muscle.

Figure 5. Blistering and darkening of the digits of case 1 on hospital day 2.

Figure 6. Intraoperative photos of case 1 on hospital day 6.

The patient was discharged 2 weeks post-injury and, at 1 week post-amputation, fungal organisms (Fusarium species) were found at the margins of the soft tissue in the amputated arm. The patient was not prescribed antifungal therapy because there was low concern and no clinical signs of systemic fungal invasion; plus, the limb had already been amputated. The patient was seen for a 2-month follow-up and was found to be healing appropriately without any postoperative stump infection (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Two-month follow-up of case 1.

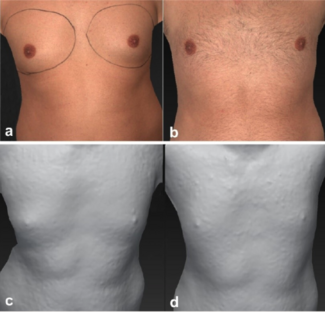

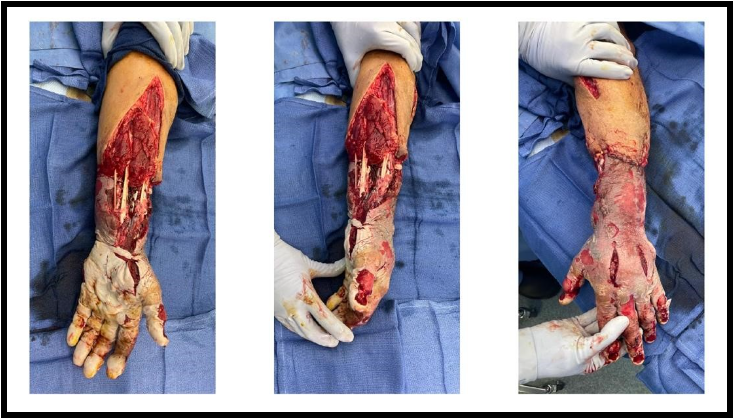

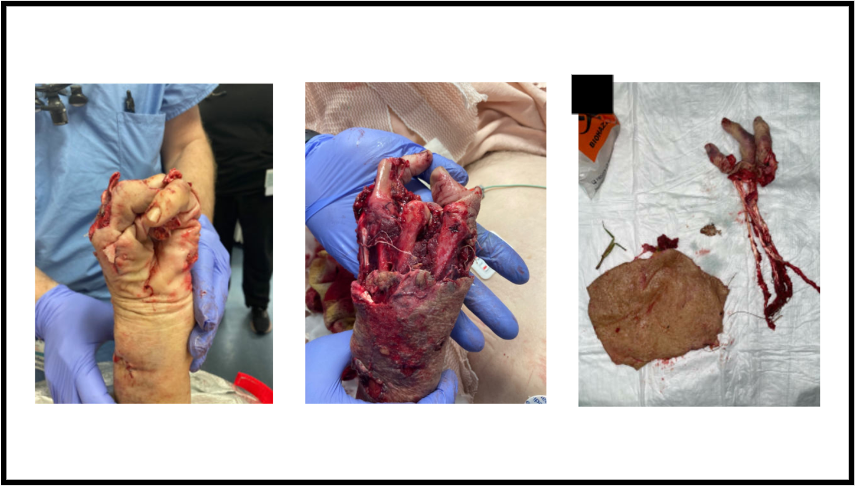

Case 2. A 77-year-old woman with a past medical history significant for hypertension and rheumatoid arthritis presented to our hospital after she sustained an alligator bite to her left forearm and leg while walking her dog. She sustained a degloving injury to her left leg, avulsion injuries to the left calf and hand, and multiple puncture wounds to the right knee; 3 digits on the left hand were traumatically amputated in the assault (Figures 8-10).

Figure 8. Initial emergency department presentation of the left upper extremity of case 2.

Figure 9. Initial emergency department presentation of the left lower extremity of case 2.

Figure 10. X-ray of the left hand of case 2.

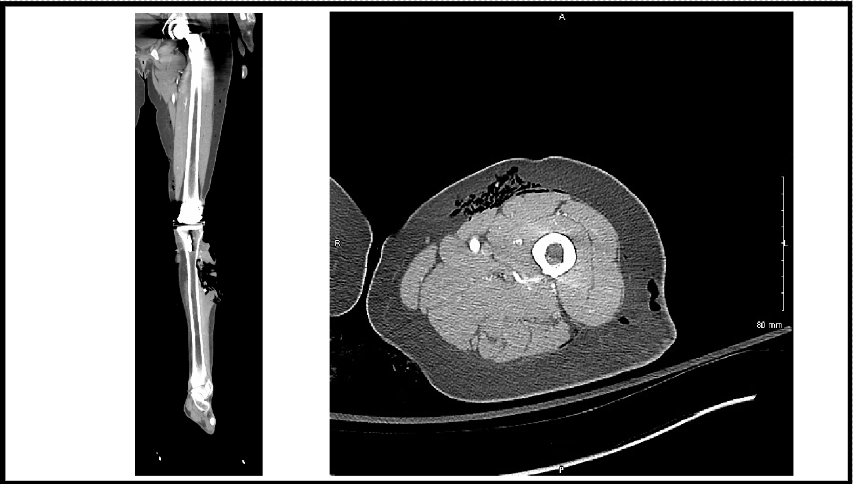

Upon arrival, she received a tetanus shot and was placed on cefepime, vancomycin, and metronidazole. Grossly, there was extensive soft tissue damage to the left forearm and hand, in addition to exposed metacarpal bones and complete amputation of the index, long, and ring fingers on the left hand. Radiographs of the wrist demonstrated a comminuted open distal ulna and a comminuted articular distal radius fracture. Moreover, the left radial and ulnar arteries signals were lost distal to the site of the wrist fracture, and the distal tissue was cold to the touch. Computed tomography scan demonstrated a Morel-Lavallée lesion on her left thigh (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Computed tomography (left) of the alligator bite to the lower leg and (right) of the Morel-Lavallée lesion on the upper thigh of case 2.

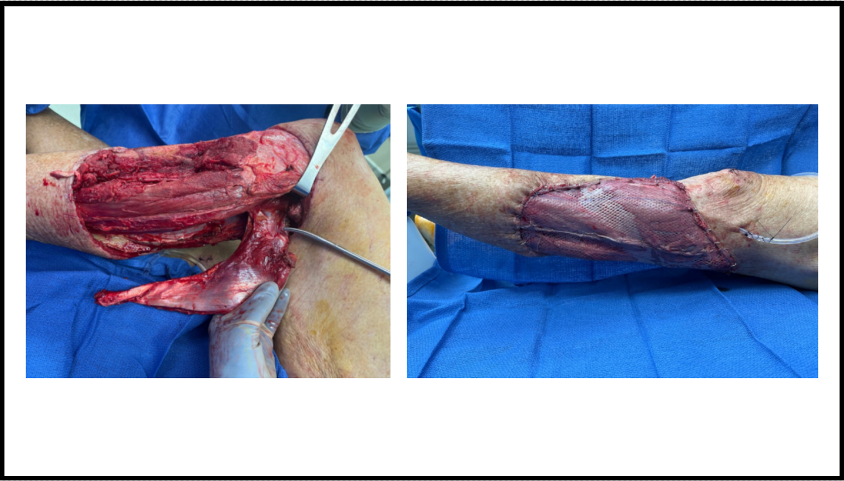

She was brought to the OR for debridement of her left upper and lower extremities. Guillotine amputation at the level of the forearm fracture site was deemed the best option for the patient based on the level of tissue damage and loss of vascularization. Negative pressure wound therapy was utilized over the left forearm wound and leg where the tibia and fibula were exposed. On hospital day 2, she returned to the operating room for additional debridement, in which the Morel-Lavallée lesion was addressed. Vancomycin and tobramycin powder were placed in the wounds as local prophylactic antibiotics, and her antibiotic regimen was changed from doxycycline to metronidazole. Imaging demonstrated subcutaneous air throughout the left knee, and, as there was some concern for fasciitis, she was also placed on clindamycin. Five days post-injury, she underwent lateral gastrocnemius flap, local peroneus longus musculocutaneous advancement flap, and split-thickness skin graft to cover the exposed tibia/fibula (Figure 12). She was discharged on hospital day 13 with intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy for 6 weeks. Her postoperative recovery was uneventful, and she was transferred to a rehabilitation facility closer to home.

Figure 12. Left lower extremity wound intraoperative flap procedure of case 2.

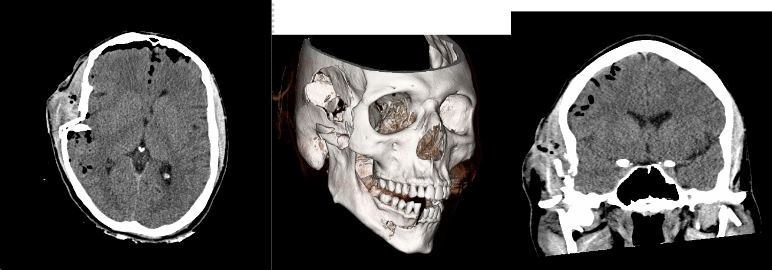

Case 3. A 34-year-old man with no significant past medical history presented to the hospital after being bitten by an alligator while recreationally swimming in a lake. On presentation, he had a large right-sided facial avulsion with facial nerve injury, multiple puncture wounds to the posterior scalp, and 1 puncture wound to his chest (Figure 13). Further work-up demonstrated a depressed skull fracture with pneumocephalus and a right parasymphyseal mandible fracture (Figure 14).

Figure 13. Initial emergency department presentation of case 3.

Figure 14. Case 3: (left) axial plane head shown on computed tomography (CT); (middle) 3-dimensional bone reconstruction of the CT; and (right) CT of the coronal plane.

The patient was taken urgently to the OR with both neurosurgery and otolaryngology. He underwent right-sided frontotemporal craniotomy for elevation of the depressed skull fracture, subdural hematoma evacuation, maxillomandibular fixation, open reduction and internal fixation of the mandible fracture, and primary closure of his facial and extremity lacerations. He was started on doxycycline, ciprofloxacin, and metronidazole for prophylaxis for a 2-week course, and he received a diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis booster (Tdap) vaccine upon arrival at the ED. He was discharged 8 days after his initial presentation. Arch bars were removed in the OR after 1 month.

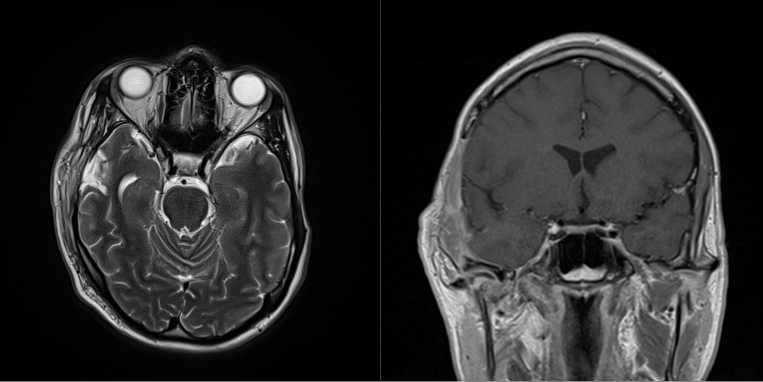

Two months after his injury, the patient developed purulent drainage from the scalp surgical wound (Figure 15). He was started with vancomycin and cefepime empirically. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a fluid collection concerning for abscess; therefore, he was taken to the OR for irrigation and debridement (Figure 16). Intraoperative cultures grew Staphylococcus epidermidis, and the patient was placed on 6 weeks of IV vancomycin for cerebritis. Four months following his initial injuries, he underwent a cranioplasty with a PolyEtherEtherKetone (PEEK) implant fully covered by a temporalis muscle flap. There were no postoperative complications, and the patient was healing well at his 6-month follow-up without any malocclusion or wounds (Figure 17).

Figure 15. Purulent discharge from the surgical incision of case 3.

Figure 16. Case 3: (left) axial and (right) coronal magnetic resonance imaging of the presentation with purulent discharge.

Figure 17. Post-cranioplasty of case 3.

Discussion

Alligator bites are uncommon but devastating injuries, and knowledge of how to treat these complicated injuries is important for the reconstructive plastic surgeon, especially those who practice in alligator-populated areas. Not surprisingly, case reports comprise the majority of the published research on this topic. High-powered studies are lacking within this patient population, likely because of the infrequency of attacks. We present 3 patient cases and a systematic review of the literature of alligator and crocodile bites to contribute novel patient data to the current literature on the subject and effectively summarize the current standards of care in treating patients with alligator-inflicted injuries.

Demographics

Alligator and crocodile bites are rare in the United States and are largely isolated to the southeastern region of the country.2 Amongst these states, Florida not only has the largest alligator population but also the highest number of reported alligator attacks compared with all the other states combined, accounting for 85% of bites.2 In our review, we found that adult males were more likely to get bitten, with approximately half of the bites involving the upper extremities, and 95% of cases being nonfatal.

Mechanics of bite trauma

An alligator bite causes damage by both sharp and penetrating mechanisms. The American alligator, Alligator mississipiensis, and its crocodilian relatives have some of the strongest bite forces in nature, over 2000 per square inch (PSI), because of a unique arrangement of strong jaw closing muscles and weak opposing musculature.22 In comparison, sharks bite with 330 PSI and lions bite with 940 PSI.10 Both alligators and crocodiles are capable of amputating an extremity and transecting a torso.10,22 The strength of the bite is not the only factor that makes bites so deadly; an alligator’s 80 teeth are conical, enabling puncture wounds and tearing with movement.22,23 The feeding habits of crocodilian include a spinning maneuver, or death roll, which generates great shear forces to incapacitate its prey through an avulsive mechanism.22,23 The crushing and shear forces generated by these reptiles can cause severe skeletal and soft tissue injuries, such as the Morel-Lavallée lesion sustained by the patient in case 2, which is defined as a closed degloving injury characterized by a separation of the subcutaneous tissue from the underlying fascia.24 The Morel-Lavallée lesion can further complicate an alligator bite because of the presence of hemolymph and necrotic fat effusing into the space.24

Infectious considerations

It is important to recognize the diverse microbiomes that exist in these large animals when treating these bites. The microbiology of an infected bite wound correlates strongly with the native microbiota of the animal, the animal’s prey, and their environment. Polymicrobial animal bite wounds, seen from alligator bites, host both aerobic and anaerobic bacterial species.25,26 Given the low incidence, research is lacking on standardized treatment for alligator-inflicted wounds. However, infection prevention is of critical importance, as infection can exacerbate the dramatic damage inflicted on skin, muscle, tendons, and bones from the initial assault with further tissue necrosis and potential need for amputation.

The oral microbiome of the American alligator includes aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, and even fungal species.26 The current literature shows that there are over 20 pathogenic species in alligator mouths, and these include mostly gram-negative bacteria and anaerobes.25 An analysis of 10 different alligator oral cavities found extensive variety in the different oral flora.25 Proteobacteria, such as Aeromonas hydrophilia and Proteus vulgaris, Clostridium, Pseudomonas species, Bacteroides species, and Fusobacteria are all dominant isolates from the oral cavity of alligators.25,26 Bacteria found in water, such as Vibrio vulnificus and Citrobacter species, should be considered potential infectious agents of any marine bites.21,27 The current antibiotic regimen recommendation based on the nature of these microorganisms is broad spectrum antibiotics, with an emphasis on coverage of gram-negative bacteria. Aeromonas infections in particular can present with cellulitis or bullae and necrosis; this also represents the most reported microbial organism in alligator bites.25 Coverage for Aeromonas includes fluoroquinolones, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, or a cephalosporin of the third/fourth generation.27 Tetanus inoculations are also recommended if the patient vaccination history is unknown.27 The systematic review supported generalized gram-negative coverage with ceftriaxone, and anaerobic coverage with metronidazole with step-up therapy to penicillin antibiotics.

Of note, in case 1, the fungus Fusarium was found growing on the amputated limb specimen. This is significant because it is the first reported case of a fungal infection after an alligator bite in medical literature. Fusarium is the second most common opportunistic mold in humans and can be highly invasive and difficult to treat.26 Fusarium and other fungi have been demonstrated to inhabit the oral microbiome of alligator mouths.26 This finding suggests that fungal infections should be considered in acute or chronic wound infections after an alligator or crocodile bite.

Surgical management

An alligator victim should first and foremost be treated as a trauma patient with the appropriate advanced trauma life support–based triage with primary, secondary, and tertiary trauma surveys. Alligator bites can potentially cause significant hemorrhage, and patients can present with significant blood loss and be acutely unstable. In 2 of our cases, the patients were hemodynamically unstable and required multiple units of blood during resuscitation. Once the patient is stabilized, reconstructive surgical planning can begin.

Alligator bites pose a great challenge when attempting to salvage remaining tissue because of the bacteria they harbor and the forceful mechanism of the attack. Initial management requires thorough irrigation and debridement of the wound site, as well as prophylactic antibiotics because aquatic environments and alligator mouths contain a plethora of microorganisms that can infect the injury.23 Radiographs should be taken to assess any fractures or bone damage from the crushing force of an alligator bite.23,28 Because of the concern of infection, the wound should not be closed by primary intention, but left to heal secondarily.6,29 In cases where neurovascular or tendinous structures are exposed, soft tissue coverage is necessary to attempt to salvage and reconstruct the limb.30 In bite injuries with exposure of nerves, vessels, and connective tissue, dermal matrix substitutes can be used in the early post-injury phase, especially if a healthy vascular bed is intact.31 For smaller wounds, tissue from local regions may be mobilized to provide coverage. For deep, traumatic wounds that lack adequate blood supply and have exposed nerves, vessels, tendon without paratenon, or bone without periosteum, regional or free flaps may be indicated for coverage.30,31

For severely traumatic injuries, such as crush or avulsion incidents, amputation may be the most functional option. The decision to amputate incorporates factors such as ischemia time, vascular injury, nerve damage, and bone involvement.32 There are multiple clinical decision-making indices predicting salvage rates. An analysis of 70 lower extremity injuries led to the creation of a limb salvage index scoring system that considers 7 factors: artery, nerve, bone, skin, muscle, deep vein, and warm ischemia time, where a score of 6 or higher is suggestive of no chance of limb salvage.32 A limb traumatized by an alligator may be determined to be a truly “mangled extremity,” in which vascular tissues, muscle, nerves, and bones are devastated and amputation is the only feasible outcome.9,27 Providers should also be on high alert for compartment syndrome when dealing with limbs that sustain crush injuries.27 In terms of limb salvage, in case 1, the extremity was still attached, and the median and ulnar nerves were still intact without significant damage to the patients’ digits; therefore, limb salvage was attempted. In the second case, the injury involved severe degloving and mangling of the digits; it was determined that attempted salvage would have been futile and had potential to cause the patient additional morbidity secondary to longer OR times and multiple return trips to the OR.

Recommendations and future directions

From our 3 recent patient care experiences in Florida and comprehensive review of the literature, we provide the following recommendations: (1) patients who sustain alligator or crocodile bites should be emergently transferred to a tertiary center offering interdisciplinary care; (2) care should be taken to initiate an appropriate antibiotic regimen ensuring adequate coverage of marine organisms as well as known organisms colonizing an alligator’s oral cavity; (3) there should be a low threshold for early operative intervention, given the potential to reduce microbial burden through thorough debridement as well as potential preservation of vital structures and control of hemorrhage as applicable; (5) these patients will likely require a staged approach to washout and reconstruction; (6) initial attempts should be made for limb salvage, but patients may ultimately require amputation because of the mechanism of injury; (7) if amputation is performed, targeted muscle reinnervation should be considered to optimize prosthetic outcome; and (8) reconstruction beyond the zone of injury may be required long-term to optimize form and function of the ravaged body part.

Conclusions

Alligator and crocodile bites are rare but devastating injuries that can require the expertise of the reconstructive plastic surgeon. Initial injury results from both penetrating and blunt high-energy forces; this dual nature of damage is due to an alligator’s tooth shape and sharpness, massive masticatory forces, and the common “death roll” after bite. Management includes acute resuscitation and stabilization, broad spectrum antibiosis, and surgical debridement and reconstruction. Plastic surgeons, especially those practicing in areas with alligator and crocodile populations, should be aware of the unique nature of these injuries and treatment strategies.

Acknowledgments

Authors: Sarah Moffitt, BS1; Bilal Koussayer, BS1; Kristina Buller, DO2; Meredith G. Moore, MD2; Mariel McLaughlin, MD2; Jenna Stoehr, MD2; Riley Schlub, MD3; Michael Doarn, MD3; Jared Troy, MD2

Affiliations: 1Morsani College of Medicine, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida; 2Department of Plastic Surgery, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida; 3Florida Orthopedic Institute, Temple Terrace, Florida.

Correspondence: Sarah Moffitt, BS, USF Health Morsani College of Medicine, 560 Channelside Dr, Tampa, FL 33602, USA. Email: moffitts@usf.edu

Ethics: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Two patients shared their hospitalizations in the news and were therefore asked for consent again, with a signed statement of informed consent to publish any descriptions, photographs, and/or video of identifiable material that are essential and clinically relevant to the manuscript.

Disclosures: The authors disclose no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests.

References

- Savu AN, Schoenbrunner AR, Politi R, Janis JE. Practical review of the management of animal bites. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9(9):e3778. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000003778

- Langley RL. Adverse encounters with alligators in the United States: an update. Wild Environ Med. 2010;21(2):156-163. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2010.02.002

- Alligator data and reports. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/wildlife/alligator/data/

- Sartain SE, Steele RW. An alligator bite. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2009;48(5):564-567. doi:10.1177/0009922808326299

- Shepherd SM, Shoff WH. An urban northeastern United States alligator bite. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(5):487.e1-3. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.11.004

- K A, Ayyan SM, Ezhilkugan G, Kumar P, Rajendran G. A rare case of limb-threatening injury secondary to extrinsic vascular compression following crocodile bite. Wilderness Environ Med. 2022;33(3):355-360. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2022.05.004

- Pomares G, Pauchard N, Dap F, Dautel G. An articular spacer for metacarpophalangeal fracture: the story of a crocodile bite. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2016;35(5):371-374. doi:10.1016/j.hansur.2016.07.004

- Venter M, Kelly A, Boffard K, Pretorius R, Younus A. African Nile crocodile bite of the forearm: a case report. East African Orthopaedic Journal. 2020;14(2):102-107.

- Harding BE, Wolf BC. Alligator attacks in southwest Florida. J Forensic Sci. 2006;51(3):674-677. doi:10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00135.x

- George A, Lee SK, Carrillo EH. Alligator wrestling: the ultimate wrestling match. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(3):E113. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31821e10d8

- Lew F, Khalaf R, Vega E, Stieg F, Miner J. Non-trauma community hospital management of head and neck wound from alligator bite. Cureus Journal of Medical Science. 2012. https://www.cureus.com/posters/532-non-trauma-community-hospital-management-of-head-and-neck-wound-from-alligator-bite

- Alelign D, Tena T, Tessema M, Kidanewold A. Drug-resistant aerobic bacterial pathogens in patients with crocodile bite wounds attending at Arba Minch General Hospital, southern Ethiopia. Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:8669-8676. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S395046

- Bonito C, Sisti G, Fambrini M. Clinical image: crocodile bite. J Pak Med Stud. 2013;3(3):118-119.

- Chiu CH, Kuo YW, Hsu HT, Chu KS, Shieh CF. Continuous infraclavicular block for forearm amputation after being bitten by a saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus): a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2009;25(8):455-459. doi:10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70542-X

- Doering EJ III, Fitts CT, Rambo WM, Bradham GB. Alligator bite. JAMA. 1971;218(2):255-256. doi:10.1001/jama.1971.03190150075025

- Kumaravel S, Rehman SM, Chinnadurai MC, Sivasenthil A. A case of crocodile bite injury: the management, analysis and the literature review. Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical Sciences. 2015;6(2):1628-1633

- Mazingi D, Mbanje C, Muguti GI, Chitiyo ST. A case report of a bite from the Nile Crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) managed with regional anesthesia. Wilderness Environ Med. 2019;30(4):441-445. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2019.06.013

- Savarirajo JC, Sri Kumar SK, Boniface Deyoi Y, Faruk NA, Kamaruddin F. Bujang Senang – a myth or reality? incidence of crocodile related injuries in West Borneo. Malaysian Orthopaedic Journal. 2017;11(Suppl. A): PT13D.

- Schmidt E, Kulendran K, Green D, Chong HI. Penetrating skull injuries from a crocodile bite: general surgery in Far North Queensland. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91(9):1943-1945. doi:10.1111/ans.16607

- Vanwersch K. Crocodile bite injury in southern Malawi. Trop Doct. 1998;28(4):221-222. doi:10.1177/004947559802800411

- Wamisho BL, Bates J, Tompkins M, Islam R, Nyamulani N, Ngulube C, Mkandawire N. Ward round--crocodile bites in Malawi: microbiology and surgical management. Malawi Medical Journal. 2009;21(1):29-31. doi:10.4314/mmj.v21i1.10986

- Fish FE, Bostic SA, Nicastro AJ, Beneski JT. Death roll of the alligator: mechanics of twist feeding in water. J Exp Biol. 2007;210(Pt 16):2811-2818. doi:10.1242/jeb.004267

- Caldicott DGE, Croser D, Manolis C, Webb G, Britton A. Crocodile attack in Australia: an analysis of its incidence and review of the pathology and management of crocodilian attacks in general. Wilderness Environ Med. 2005;16(3):143-159. doi:10.1580/1080-6032(2005)16[143:CAIAAA]2.0.CO;2

- Nair AV, Nazar P, Sekhar R, Ramachandran P, Moorthy S. Morel-Lavallée lesion: a closed degloving injury that requires real attention. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2014;24(3):288-290. doi:10.4103/0971-3026.137053

- Flandry F, Lisecki EJ, Domingue GJ, Nichols RL, Greer DL, Haddad RJ Jr. Initial antibiotic therapy for alligator bites: characterization of the oral flora of Alligator mississippiensis. South Med J. 1989;82(2):262-266. doi:10.1097/00007611-198902000-0002

- Keenan SW, Elsey RM. The Good, the bad, and the unknown: microbial symbioses of the American alligator. Integr Comp Biol. 2015;55(6):972-985. doi:10.1093/icb/icv006

- Noonburg GE. Management of extremity trauma and related infections occurring in the aquatic environment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(4):243-253. doi:10.5435/00124635-200507000-00004

- Thomas N, Brook I. Animal bite-associated infections: microbiology and treatment. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2011;9(2):215-226. doi:10.1586/eri.10.162

- Mekisic AP, Wardill JR. Crocodile attacks in the northern territory of Australia. Med J Aust. 1992;157(11-12):751-754. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1992.tb141275.x

- Ng ZY, Salgado CJ, Moran SL, Chim H. Soft tissue coverage of the mangled upper extremity. Semin Plast Surg. 2015;29(1):48-54. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1544170

- Bashir MM, Sohail M, Shami HB. Traumatic wounds of the upper extremity: coverage strategies. Hand Clin. 2018;34(1):61-74. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2017.09.007

- Russell WL, Sailors DM, Whittle TB, Fisher DF Jr, Burns RP. Limb salvage versus traumatic amputation. A decision based on a seven-part predictive index. Ann Surg. 1991;213(5):473-480; discussion 480-481. doi:10.1097/00000658-199105000-00013